Yves here. I joked that I majored in the Industrial Revolution in England and France, including its literature. And when I was in school, class influence and the experience of the lower orders was a hot topic. Yet oddly, for the most part, the impact slavery was largely ignored.

By Stephan Heblich, Munk Chair of Economics University Of Toronto, Stephen Redding, Harold T. Shapiro Professor in Economics Princeton University, and Hans-Joachim Voth, UBS Foundation Professor of Economics Universitat Zurich. Originally published at VoxEU

To what extent the wealth derived from slavery contributed to Europe’s economic growth has been a hotly debated question for more than two centuries. Most economists studying the question have looked at national aggregates. This column examines geographically disaggregated data on the impact that slavery wealth had on Britain’s industrial development. The authors find that slaveholding areas were less agricultural, closer to cotton mills, and had more property wealth. Not only did the slave trade affect the geography of economic development after 1750, it also accelerated Britain’s Industrial Revolution.

Was Europe’s rise to riches built on the blood, sweat, toil, and death of enslaved people? Europeans enslaved millions of men and women on the African continent during their colonisation of the Americas. Those who survived the transatlantic voyage were forced to labour on sugar, tobacco, cotton, and coffee plantations in the Caribbean and in North and South America. In the process, Europeans accumulated vast wealth, either from the slave trade itself, from plantation production, or from the wider triangular trade between Europe, Africa, and the Americas. Growth in Europe took off during the century when the slave trade and overseas slavery in European colonies reached their greatest scale. To what extent did slavery wealth contribute to the growth and economic development of modern Europe?

The idea that slavery and the trade in enslaved human beings jumpstarted the industrial revolution is almost as old as economics itself. Adam Smith famously saw slavery as inherently inefficient, and believed that Britain’s colonial possessions in the West Indies drained the nation’s resources. Karl Marx, on the other hand, argued in Das Kapital (1867) that modern industrial capitalism was built on the capital accumulation facilitated by slavery: “the veiled slavery of the wage workers in Europe needed, for its pedestal, slavery pure and simple in the new world. . . capital comes dripping from head to foot, from every pore, with blood and dirt”.

The topic has also been hotly debated by economic historians. One influential line of research agrees with Marx, arguing that Britain accumulated vast wealth from the triangular trade and used this wealth to finance its industrial revolution (see e.g. Williams 1944, Darity 1992, Solow 1993, and Inikori 2002). In contrast, another prominent strand of work argues that profits from the slave trade were no higher than from other lines of business, while absolute levels of profit from the slave trade were small relative to the size of the British economy, such that slavery played a relatively minor role in Britain’s industrial development (including Engerman 1972, Eltis and Engerman 2000, and Knick Harley 2013).

Most analysis of this question has looked at national aggregates. In our recent work (Heblich et al. 2022), we examine geographically disaggregated data on the impact of slavery wealth on industrial development. To do so, we collect and use new data on the geography of slaveholding and on economic development in Britain. We combine these with a new source of exogenous variation in slavery wealth and a quantitative spatial model. To measure wealth from slaveholding, we use a unique data source: Britain, through the Abolition of Slavery Act in 1833, provided compensation payments to existing slaveholders. These compensation payments were substantial, equal to £20 million in historical prices, equivalent to around 40% of the government’s budget and 5% of gross domestic product (GDP). In today’s money, this is equivalent to from £2–£108 billion. We use individual-level data on these compensation payments to more than 25,000 slaveholders, as compiled by historians over more than a decade in the Legacies of British Slavery database (Hall et al. 2014). This allows us to directly measure slavery wealth for each slaveholder – in terms of the total number of enslaved persons and their assessed value – and to locate these slaveholders geographically. We combine this measure of slaveholder wealth drawn from claims for compensation with detailed information on population, employment structure, and property values.

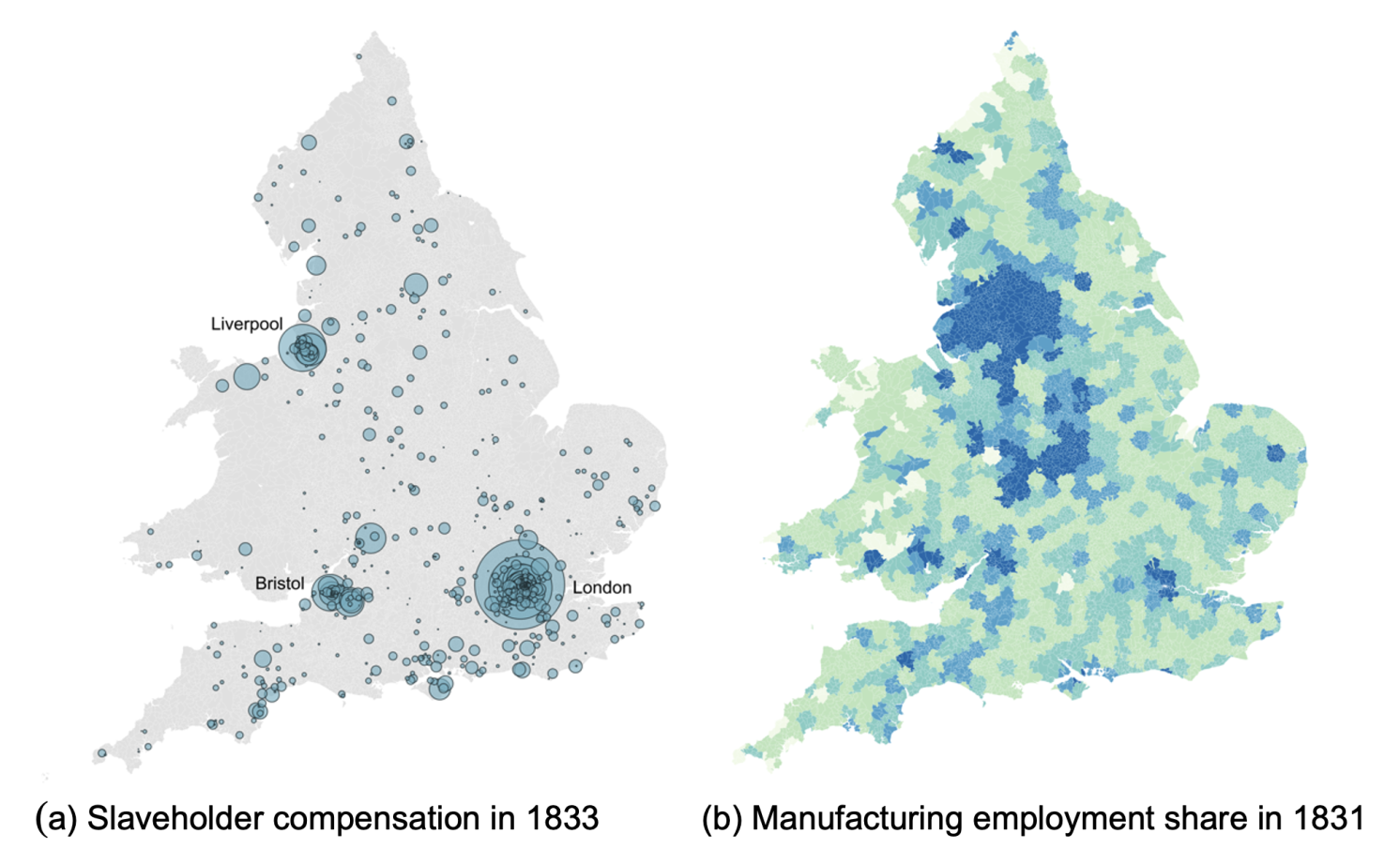

Across Britain, industrial activity and slavery wealth at the time of abolition are strongly correlated. Figure 1(a) displays slavery compensation claims across parishes within Britain. The size of the blue circles is proportional to the amount of slavery compensation awarded in current price 1833 pounds sterling. We find the largest concentrations in the areas surrounding the three ports most heavily involved in the slave trade and the products of the slave economy (particularly sugar, tobacco, coffee, and cotton): Liverpool in the North-West, Bristol in the South-West, and London in the South-East. But slaveholding extends throughout much of England and Wales, particularly in coastal regions, and in the main population centres.

In Figure 1(b) we show the manufacturing employment share across parishes in 1831. By that time, the manufacturing employment share for England and Wales as a whole was approximately 42%, and we see the emergence of industrial agglomerations in the North. However, agriculture still employs approximately 27% of the population, and there is substantial heterogeneity in agricultural specialisation across regions, with agriculture still accounting for more than 60% of employment in some counties. Comparing the two figures, there is a clear positive correlation between manufacturing employment shares and slaveholder compensation.

Figure 1 Slaveholding and structural transformation in the 1830s

Notes: Left panel: Slaveholder compensation in each parish in 1833 pounds sterling; size of blue circles proportional to the total value of slaveholder compensation in each region. The largest three slave trading ports by enslaved persons embarked are labelled. Right panel: Manufacturing employment share in each region in the 1831 census; darker blue colours correspond to higher values; lighter green colours correspond to lower values.

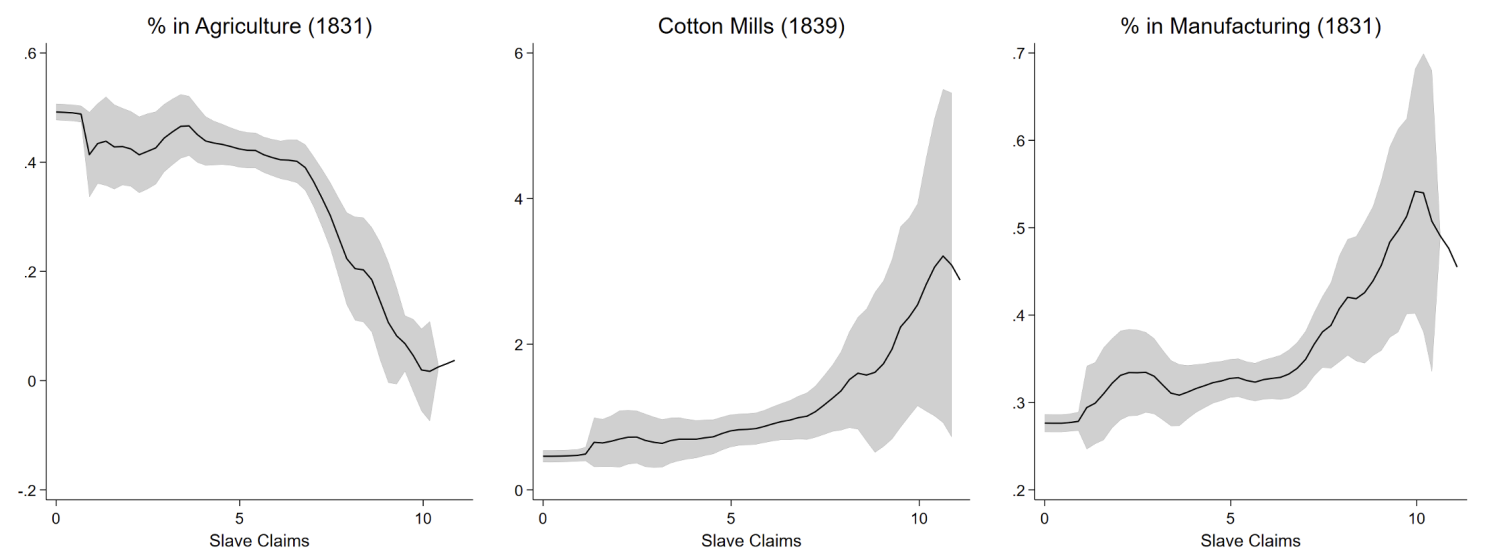

In Figure 2, we provide further evidence for the correlation between structural transformation and slaveholding using three different indicators: the agricultural employment share in 1831 (left panel), the number of cotton mills in 1839 (middle panel), and the industry employment share in 1831 (right panel). We show the fitted values and 95% confidence intervals from local polynomial regressions of all three measures on the number of enslaved persons claimed in 1833. We find that areas with extensive slaveholding have lower agricultural employment shares, more cotton mills, and higher manufacturing employment shares.

Figure 2 Structural transformation and slaveholding in the 1830s

Note: In all three panels, the horizontal axis shows total number of enslaved people in each hexagon in 1833; vertical axes show agricultural employment share in 1831 (left panel), number of cotton mills in 1839 (middle panel), and manufacturing employment share in 1831 (right panel); dark line shows fitted values from local polynomial regression; grey shading shows 95% confidence intervals. Slave claims and the number of cotton mills are inverse hyperbolic sine transformed.

Many slave traders eventually became slaveholders, investing their wealth in West Indian plantations. We exploit this fact to provide evidence that this correlation between economic activity and slaveholding is causal. Our new instrumental variables estimation strategy starts with the fact that in the age of sail, the idiosyncrasies of wind and weather heavily influenced the duration of transatlantic voyages. Crowded and inhumane conditions on slave voyages led to high rates of mortality during the Middle Passage. A primary determinant of mortality for enslaved people was voyage duration. As voyage times increased because of unfavourable winds, water began to run out, and infectious diseases spread, raising mortality among the enslaved. High mortality reduced slave traders’ profits, making their continued involvement in the trade less likely. Hence, inclement weather shocks directly reduced wealth, and also induced exit from the slave trade, thereby reducing slaveholder wealth in 1833 (at the time of abolition). We track down the location of slave traders’ ancestors. Many traders, once rich, returned to their ancestral family homes. In places with more exposure to the slave trade through ‘family trees’, we typically find greater slave wealth in 1833. The effect is large: for every one standard deviation increase in voyage outcome of a slave trader, we find a 0.16 standard deviation rise in slaveholder wealth.

A range of measures of industrial activity are strongly related to this exogenous component of slaveholder wealth. A one standard deviation increase in slaveholder wealth predicted by our instrument leads to a 1.76 standard deviation increase in steam engines, a 0.52 standard deviation increase in rateable values, a 0.61 standard deviation decrease in agricultural employment contrasted by a 0.86 standard deviation increase in manufacturing employment, and a 0.77 standard deviation decrease in the average distance to the ten nearest cotton mills in 1839.

To assess the implications of these findings, we combine these empirical estimates with a dynamic specific-factors model of the spatial distribution of economic activity across industries and locations within Britain. Greater slavery wealth alleviates collateral constraints and stimulates domestic capital accumulation, which in turn induces an expansion in the capital-intensive domestic manufacturing sector, and a decline in the land-intensive agricultural sector. Some locations benefited enormously from Britain’s involvement in slavery. Places with the highest levels of slavery wealth saw increases in total income of more than 40%, with population increasing by 6.5%, capitalists’ income rising by more than 100%, and landlords’ incomes declining by just over 7%.

At the aggregate level, we find an increase in national income of 3.5%. This is sizeable relative to conventional estimates of the welfare gains from international trade, where Bernhofen and Brown (2005) find an upper bound of 9% for 19th-century Japan. It also corresponds to roughly a decade of growth of gross domestic product (GDP) at the time. Capital owners were the largest beneficiaries, with an increase in their aggregate income of 11% due to the direct income from investments in colonial plantations and the induced expansion in domestic investments. Landowners experience small aggregate income losses of just under 1%, because of the reallocation of labour away from agriculture. Expected worker welfare rises by 3%, because of the substantial wage increases in slaveholding locations, and the reallocation of economic activity towards those locations.

Taken together, our findings suggest two important conclusions. First, involvement in the slave trade and wealth derived from slaveholding had an important effect on the geography of economic development during the British industrial revolution. While the sudden re-ordering of economic prominence in the period after 1750 has long seemed puzzling (Crafts 2014), our evidence offers a clear explanation for why some locations suddenly took off economically. Second, our results strongly suggest that Marx was right: slavery wealth accelerated Britain’s industrial revolution.

See original post for references

I read this paper when I first came out and it was very interesting. I recommend reading the full paper. There are some nice anecdote about the concentrated effect of slaving wealth in certain locales: I think there are several coastal towns with high concentrations of ship captains, their extended families, local gentry, shipbuilders etc. all profiting from the triangular trade in the south-west, in ports that are now delightful genteel second-home and retirement places. Somebody had to pay for all those Regency villas and it was not just the effect of the Napoleonic wars blocking off the Grand Tour for aristocrats. There is a reason why ship’s captains houses are so grand….

Side note – the cod trade was also a great source of wealth and on Jersey, many captains’ houses are built with “cod’s eye” inlay decorations on the bannisters and newel posts.

When I did an independent study on slavery systems in the Americas under Dr. Jonathan Walton (R.I.P.) back in the ’80s, there was an emphasis on Gunnar Myrdal’s research and data, all of which spoke to the profitability of the slave trade and slave-owning. It wasn’t hard for me to grasp because having grown up on a farm with livestock, it was obvious that slaves were treated just like livestock, a commodity with value to be treated as such. A sane farmer does not mistreat livestock, and it was obvious that the profitable plantations were run like businesses.

In the ’80s, this was OK to teach. Now I worry that the 1619 Project has buried class and capitalism in its rush to blame racism for everything. When I was growing up on a farm, I was not racist in my dealings with cattle, I was sociopathic. Cattle were meat on the hoof and cared for as such. Slaves are like robots you have to feed; only a fool would fail to feed and care for their human robots.

Racism is not the real horror: reducing human beings to pencil scratches in a profit/loss ledger is the greater crime.

> Now I worry that the 1619 Project has buried class and capitalism in its rush to blame racism for everything.

Over the last decade, there has been some really wonderful scholarship done on slavery (and one might ask whether that’s why the history profession is in trouble). Needless to say, the 1619 Project is neither wonderful — except possibly in the tenacity of its kudzu-like spread — nor scholarship.

Just how you treat what you think of as animals depends on what is the most profitable way. The death rate of slaves in the Americas was highest on the Caribbean plantations and in Brazil. They were truly disposable as the owners decided it was more profitable to work them to death and import more slaves as replacements. In the United States, they were considered too valuable and used as collateral and in inheritance, exactly as a house, land, or a car.

After Reconstruction, when blacks were being terrorized and murdered into subjugation, those sentenced to hard labor, often for spurious reasons, were treated much more harshly than their parents and grandparents. It has been called “slavery under another name,” but the death rate was almost certainly higher, certainly the work and living conditions were. For their enslavers, there was no reason to keep them healthy or even alive as there was a ready supply of people to effectively kidnap and work to death; they were not property that could be used as collateral, inheritance, or a store of wealth.

results strongly suggest that Marx was right: slavery wealth accelerated Britain’s industrial revolution.

I think a significant part of Venice’s dominance in trade and its accumulation of wealth in the 13th and 14th centuries was attributable to galley slaves so it’s not surprising that it also contributed to Britain’s.

Perhaps Marx got some insider knowledge from his best mate Friedrich Engels who’s family owned mills in Salford in the heart of the NW England textile manufacturing area. There’s an interesting tidbit on the Wikipedia entry for the Ermen and Engels textile firm that it was set-up in part with capital from Manchester after Engels senior had visited Manchester in 1837. So maybe that capital was derived ultimately from slavery? (Note: Salford is part of the same conurbation as Manchester on the opposite bank of the Irwell – the world’s first industrially polluted river(tm))

I’m not very convinced by this analysis.

Obviously people traded slaves because it brought in money. And obviously some of that money may have ended up funding some industry, just like God knows what ends up investing in high tech companies these days.

However if people are being compensated for the emancipation of their slaves, it means they kept their wealth in slaves, and did not invest that wealth in manufacturing. And that’s the pattern the map shows: more manufacturing and less compensation around Liverpool, more compensation and less manufacturing around London and Bristol.

This was a time of great change in Britain. Wool was the first globally traded commodity. Peasants were being kicked off the land to be replaced by sheep. So there was an increase in poverty among some, and wealth for others. And there was trade in many commodities that weren’t people, such as tea and porcelain. So there was a sudden increase in wealth for some.

Correlation does not prove causation, and I don’t see an analysis of confounding variables here. For instance, rich people tend to congregate in certain areas, unless they are tied to their land. At that time, many small land holders sold their land, and they’d often move to a larger city to be with other people like them. People in such areas would then invest their money in various things.

A place with rich people would look for “investment opportunities”. Some might fund steam-engines and others might hold slaves. Indeed my understanding is that one of the justifications at the time for compensation was that many of the slaveholders were widows, etc and their slaves provided them with a pension/annuity of sorts. So it’s probable that owning a slave who worked in the West Indies was considered a low risk investment, and only those with a higher risk tolerance and less to lose would invest in newfangled ideas such as cotton mills and the first steam trains.

This means that I don’t see any proof here that industry was significantly and directly funded by the slave trade. Perhaps there is longer version of this paper that proves this hypothesis more conclusively than the above argument.

Indeed, I would be curious to know whether the emancipation of the slaves, and the subsequent compensation, actually caused a boom in industrialization. The first passenger steam train line was opened in 1830 between Liverpool and Manchester, which led to many others. If that were the case, an argument could be made that holding slaves actually delayed industrialization, by keeping wealth offshore. Once that money had to be invested in factories, it would have led to more skilled labor and cheaper goods, the ingredients of a consumer society. Perhaps this phase could have occurred earlier had slave-holding been illegal.

(Obviously slavery is horrific, and should never have occurred. To give credit where it is due, the British did end up banning slavery and actively enforced that ban against both the Atlantic and Arab slave trade. Most slaves were traded to South America by Spain, Portugal, and to the Ottoman Empire. For instance, the Brits took Zanzibar militarily to stop that trade. On the other hand, they did not suddenly become angels: they fought China to force it to not ban the Opium trade. They developed this trade because the Chinese wouldn’t accept gold for goods but wanted silver, and Europeans sold Opium to China to get that silver.)

They appear to emphasize the investment locally of the profits of ownership, which were an order of magnitude greater than of the triangle-trade:

https://cep.lse.ac.uk/pubs/download/dp1884.pdf

Thanks for the full paper.

There was a difference in British and American slavery. The British, eventually, started to consider and treat slaves as valuable property, not something to be used up. The Americans even more so. This is not due to morality, but to wealth. Slaves often were used as collateral for loans and generally as stores of wealth.

This was why the American South was the wealthiest part of the United States. They were using slaves not only as tools, but the same as land or stocks and bonds. Wealth used to generate more wealth like with today’s oligarchs.

I could also point to the Northern banks and investment firms that became very profitable after investing in the Slavocracy. The industrial North also sold to the South everything it did not manufacture. It didn’t make much.

So, the areas getting wealthy from slavery and the areas getting wealthy from investing in that wealth did not have to be the same. Again, as in the American South and Northeast. Plantation owners were usually interested in manufacturing.

Although, just before the American Civil War, there were efforts to put slaves into factories. I want to say Birmingham, Alabama, but I really am not sure. As far as I know, they were successful or at least profitable. I have to dig into my piles of books. It should be in there somewhere. If anyone knows about this, please chime in. Someone should know more about this than is what is in my decayed memory.

I remember thinking that this is what they wanted Americans to be in the factories; it would have made the Captains of Industry during the Gilded Age quite happy just as with our current oligarchs.

Indeed. Much as the influx of gold and silver to Spain largely wound up in the hands, not of the Spanish nobility, but of those nations who sold them luxury goods.

But people trying to analyze total value chains get different results.

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-global-history/article/on-the-economic-importance-of-the-slave-plantation-complex-to-the-british-economy-during-the-eighteenth-century-a-valueadded-approach/DBB1225FF928C09689B3EEFCA8F66C55

This paper, for instance, estimates about 11% of the British economy being derived in various ways from the slave-trade. This includes knock-on effects like the effect in shipbuilding of a fairly large number of ships built to satisfy the trade, manufacture of goods demanded by Africans in return for slaves,

etc. etc.

Charles Mann has an interesting take on the growth of slavery and indentured servitude in the US in his book “1493”.

I’m not sure I buy the conclusions. There is some correlation of course, and I think they try to establish causation too but I don’t understand the reasoning.

Just looking at the map, the conclusions do not seem to hold: the Midlands and South Wales are industry-heavy with little slaveholder claims, London has relatively little industry and a lot of claims. Liverpool has a lot of both, whereas Manchester has much fewer claims.

I too am not totally convinced by the correlation. Places like Bristol and Liverpool undoubtedly benefitted from the trade in slaves but there was also the plantation ownership and the profit from that. I have no data but I would think that those profits built on slave Labour would dwarf the actual slave trade though I am open to being corrected. I say this based on cities like Glasgow and Edinburgh where just about every major street or monument is named after a Tobacco lord. The same could probably be said for cotton in an another city perhaps. So it’s kind of obvious that there was capital sloshing around in the system. If that capital was in the hands of a person that was a member of a non-conformist religion then they were barred from the “professions” and so tended to become merchant/manufacturers. They were drawn to areas where they could “invest” like Manchester for cotton textiles. Manchester was the center of this new industry because it was wet and rainy with ample water power at first then coal and it was close to the port of Liverpool. Capital was not the main factor since that was not geographically constrained. Was slave owner capital laundered through industrial development? Of course it was. Did the mill owners care where the money came from? No, just like a lot of them did not care for their workers well being – it was their station in life.

I would have thought a combination of the slave labour, colonial expropriation of land (driving monoculture for export) and mining exploitation all contributed to capital accumulation that then drove the Industrial Revolution and funding for university R&D.

As explicit colonialism ended, it continued implicitly through odious debt and structural adjustment programmes, that aimed to keep countries subservient and ensured cheap access to commodities.

I’d posit that it also had a more insidious effect on western elite / PMC culture: that of exploitation to further one’s own wealth is fair game, and a concomitant inability to collaborate to achieve win/win.

The West was right to fear communism in emerging markets – the threat of a good example. And so Russia and China have managed to emerge out of colonial poverty to develop on their own.

Further, China’s BRI would seem to be ending this game for others, which presumably is why western elites are so hysterical – they are incapable of envisioning a different approach to international relations apart from ‘our rules based order’.

Like the others, I’m not very convinced by the correlation. It looks more closely related to ports, which were the wealthiest places in the early industrial revolution, as nearly everything was funneled through the big three ports of London, Bristol and Liverpool. Up to the mid 19th Century, wealth always followed navigation routes, whether coastal ports or canals as this was by far the cheapest way to move bulk goods. A fundamental change in the geographic spread of investment occurred after 1840, when the railway boom opened up the coal and steel areas in the midlands. I’m sure capital profits from slavery had some impact, but I’ve seen no evidence that it was significant in comparison to the flow of wealth from the early colonies and the availability of cheap power (i.e. coal).

And ports are typically places where agriculture does not take place, so that inverse correlation — slaveholder places cause a decrease of agriculture in favour of industry — is a spurious one.

There is very little correlation. This “research” has no merit.

Manchester is the crucible of the modern industrial world, and had no slave-owning businesses. There were work-houses for the poor, which is a different matter.

There has long been a movement in US historians to paint the UK as a slave-owning culture, when it was first abolished in the UK in 1807, long before most other countries. Arguably an impetus to the movement for independence in the 1770s was to preserve slavery, while the UK was preparing itself to live without it.

The Roman Empire was built on slavery, as well as others. The difference in Britain was the use of machinery to replace human muscle-power, making slaves obsolete. People in the UK were burning coal for energy in industrial production before anyone else, and set the stage for the advanced world of today.

> The difference in Britain was the use of machinery to replace human muscle-power, making slaves obsolete.

Well, except for the (cotton) inputs to the machinery. Of course. See for example Specters of the Atlantic: Finance Capital, Slavery, and the Philosophy of History. I quote from the jacket blurb:

Liverpool played a key role in this circuit. From the History Guild:

The British were up to their eyeballs in slavery and its ridiculous to claim otherwise. Life being full of contradiction, Abolition started there too, but the one doesn’t wash away the other.a

Presumably the British abolition of slavery was just yet another example of pulling the ladder up behind them after having made the ascent into industrialization.

May I suggest the book Bury the Chains by Adam Hochschild? It covers the British Abolitionist Movement, like the later American Abolitionist Movement, it was not about money. It was also inconvenient for both the government and business being as it was profitable.

Yes, its easy to be cynical about motives, but there was a powerful, mostly non-conformist Christian movement against slavery which was very much based on putting morality over money. A lot of people seem to think there was no such thing as progressivism or anti-capitalism before Marx.

There was also a strong overlap between various movements, including the Irish catholic emancipation movement and anti-slavery. Frederick Douglass wrote very movingly about his time in Ireland.

I agree.

This may be what about ism but as far as I can tell pretty much every culture in history before modern times had slavery too. In some form.

As late as the very early eighteenth century, if you were Cornish you had to fear the Corsair slavers. It was only the growing power of the Royal Navy that ended that particular problem.

The article makes sense (although beyond a certain point statistical correlations leave me cold) and we do need to think about slavery in its full human context, as I think you are saying. Also the contradictions inherent in all of us when it comes to these things. Gladstone, the moralizing PM was from a family whose wealth was founded on slaveholding, for example.

The past really is a different place.

One quibble with the history guild treatment. “Britain’s African colonies” were pretty much non-existent in the 18th century. They maintained a few island and coastal forts in west Africa to facilitate the slave trade, but the slaves purchased were largely acquired from African rulers able to acquire captives. Arbitrage figured strongly, as the asking price in Africa was vastly lower than the buyers on the other end were willing to pay. British bottoms carried at least a third of the total of slaves shipped.

Interestingly, the need to eradicate the slave trade was later to become one of the public reasons during the Gladstone era for Britain’s participation in the scramble.

Lambert: I second your comment, and the one on the 1619 Project. I think the authors’ focus on profits misses the point. For more than two millennia, pre-industrial Europe, like Christendom before it, as well as the Roman and early Mediterranean empires, had very little to exchange with Asia and Africa for all the precious spices, fine rugs and quality fabrics, ignot steel (India), and fine porcelain (the ‘luxury trade’) except scarce silver, gold, and some Caucasian slaves from the Balkans.

The Age of Exploration was driven by desire to find the source of precious exotic spices (in the case of the Dutch V.O.C. to try to monopolize them), and for Christendom and later Europeans, to bypass the Ottoman Turkish control of trade routes through the Levant, the Red Sea, and Egypt. And the Industrial Revolution was driven by the need to stem the outflow of precious silver and gold specie, which was the focus of the then-prevailing economic philosophy of Mercantilism, through import substitution enabled by factory and machine production, which also served another major impetus, which was to replace relatively expensive skilled labor with machines tended by cheaper unskilled or semi-skilled workers, resulting in greatly increased productivity as well.

For England in particular, one major goal was to reverse the flow of trade in value added goods from the sub-continent of India, which included many fine fabrics that the British mill owners imitated in their mass production of fabrics that still have Indian names today, like Madras, etc. The big problem was securing a supply of commodity cotton, and Egypt was out of the question as a source due to Turkish control. The British colonies in the American South were the solution and the main source of cotton for the ‘satanic’ mills in England, and this explains British support for the Confederacy.

Incidentally, the British followed the Dutch in this Mercantilist approach, and the Dutch got rich from efficiently shipping grain, much of it from the region of Ukraine, to England to feed the factory workers, since Britain was unable to grow enough food to feed their population by the 18th Century. The Dutch accumulated so much English gold, that they could not carry it all back to the United Provinces, and this same gold became the basis for the Bank of England after the British got the upper hand on the Dutch in a series of wars and became an industrial powerhouse in the 19th Century.

Ironically, in the late 17th Century, the V.O.C. (the Dutch East Indies Company) did gain a monopoly over clove production in the Spice Islands (the Moluccas) of what is now Indonesia, and then cut down all the clove trees on every island but one, which led to massive starvation since these island had devoted all their potential farmland to spice production and traded the spice for rice and other foodstuffs. In the 18th Century, a Frenchman was eventually able to steal a clove plant and start production elsewhere, and overall, enforcing the clove monopoly was very expensive. Scholars who studied the V.O.C. tend to agree that this monopoly was not profitable in the long run. Again, I would argue that a focus on profits alone does not explain the cruel and bloody history of the spice monopoly– or that of slavery in the Americas!

But slave ownership in the Southern American Colonies and in the Southern states of the United States was essential to their economic and financial development, and slaves were used instead of money for sales of land and other property, and other transactions, since all the early US banks issued paper money of dubious value. The necessity of breeding slaves after Britain banned their import in the early 19th Century, and the essential role of slaves for both commodity cotton and other production, cannot be denied, and was the motive for the Texican rebellion after Mexico banned slavery in that same period. So, whether it was very profitable or not, slavery was essential to the success of the Industrial Revolution in the UK and the early economic development of the United States.

First abolished in the empire in 1807, I think you mean. Chattel slavery hadn’t been a thing in the British Isles for a long time. Or in most of western or central Europe, for that matter. So literal slaves had presumably been obsolete except in the imperial pales for a long time.

Like most things, the industrial revolution and associated transition to capitalism had many causes. Britain going much further than most of Europe to make land completely alienable was a big factor. Hobsbawn points out that the much more secure and prosperous status of the post-revolution French peasantry was a factor handicapping French industrial competitiveness, as the fledgeling industries of Britain benefitted from a massive influx of the newly destitute from the countryside, while those of France did not.

So would neoliberal economics consider slavery to be a form of inflation?

The total value of sugar was, IIRC, more than all the gold and silver taken out of the new world. The English sugar plantations produced more calories than England could farm at the time (again, IIRC). Cheap calories are important for the early proletariat.

I find any argument that European wealth isn’t built on slavery spurious. The whole exploring schtick was first about gold, which was traded for slaves taken from further south in Africa. The plantation system was worked out on intermediate holding islands off the coast of Africa. And then the Caribbean plantations were where the English worked out the concepts of industrial division of labor.

Almost all the trade that built wealth for the first two century or more of European imperial expansion has a direct tie to the slave trade. To suggest that it all would have happened without slavery is pretty unbelievable.

Add to that the fact that the gold and silver in the colonies were primarily mined by slaves.

I would strongly recommend commenters read the full paper (linked above). It takes 48 pages to deal with many if the reflex criticisms. The paper does depend on a lot of modelling and this makes me wary but the model assumptions seem reasonable and the data are extensive.

One of its strengths is considering slavery’s effects as a time series on land values and in the UK this means we can start from 1086! There was domestic slavery of a kind (servitude) in the feudal system but if you assume this was uniform, analysis of slaveholding shows effects from 1640.

If you look at the full paper, the geographic plots are much more interesting. They correspond to historically wealthy areas and, even if slavery did not cause that wealth, it certainly expanded it. There is a distinct pattern of non-Metropolitan slave holding, e.g. Dorset and East Devon, where Tory MP Richard Erne-Erle Plunkett Drax has his sprawling estate (longest boundary wall in Britain) and from which he still owns the Drax plantation on Barbados.

Its a fair point and it would be foolish to deny the role slave profits had on the wealth of Britain in particular, but historical economic geography tends to be full of correlations which frequently have more to do with patterns hidden from the records (such as commercial family links or even just prevailing wind patterns) which can create false correlations.

For one thing, as you imply, even defining ‘slavery’ from period is quite difficult as in reality there was something of a continuum between feudal ties, indented servitude, workhouses and actual slavery (which was always poorly defined in law), which may seem clear to modern historians but probably was not very apparent to the unfortunates who found themselves locked up.

For wider context, I’d recommend Bernard Porter’s highly readable “The Lion’s Share”. The narrative argues that empire was not particularly profitable for Britain, to the extent that the Brits might have been better off had they not bothered with the invasions, slave routes, and so on. The costs of maintaining it all (direct monetary costs, and also the psychological and societal costs) were greater than the spoils.

The book was originally published around 1980. Its final chapter drew the tantalising conclusion that the continued decline of Britain’s empire might culminate in disintegration of the UK itself. This is now coming to pass. I just checked, and there is recent update of the book with an epilogue addressing Brexit.

https://www.routledge.com/The-Lions-Share-A-History-of-British-Imperialism-1850-to-the-Present/Porter/p/book/9780367426989?utm_source=cjaffiliates&utm_medium=affiliates&cjevent=323737c0ad1c11ed8271c20b0a18b8fa

It’s also worth considering the effect of slaves as consumers. Much of the early industrial output was fairly low quality; cotton cloth vs. linen and wool, pot still rum vs. brandy and gin. What European consumers weren’t willing to buy was sold to the plantations. A similar process played out with food production, with dried cod and rice from the American colonies sold off to the Caribbean plantations. Had slaves been free to make their own clothes and grow their own food in the traditional way, early industry would have struggled to find a market for its cheaper products.

Working class people in industrial Britain were little better than slaves with hardly any rights or ability to escape from extremely unfavorable circumstances in mines, factories and the (press-ganged) military. So along with analyzing the input of official slave labour the authors should compare it to virtual slaves, the lower working classes. I suspect what you will find is that at that period due to the post-feudal but not yet adapted to higher urban population class system that poor people of all stripes were exploited to the benefit of the 1%.

Same old same old, except it was much worse back then but thanks to concerted trade union and other efforts in the ensuing century, steady improvements have been made. As Western civilization goes into a tailspin, we will probably be reverting back to those prior levels of exploitation, aka gap between rich and poor.