Yves here. The modest headline claim about oil prices and inflation seems reasonable, if nothing else due to lead and lag effects, as well as the ability of businesses and consumers to a degree to curtail energy use when prices rise.

However, the CEPR paper summarized in this article contends that oil prices don’t have as much impact on inflation as conventionally assumed, and bases that claim on an analysis of retail gas prices v. consumer inflation.

Due to the hour, I confess to not having read the underlying CEPR study. However…huh? First, due to changes in refining spreads over time, changes in oil prices no way, no how change in a 1:1 relationship to prices at the pump.

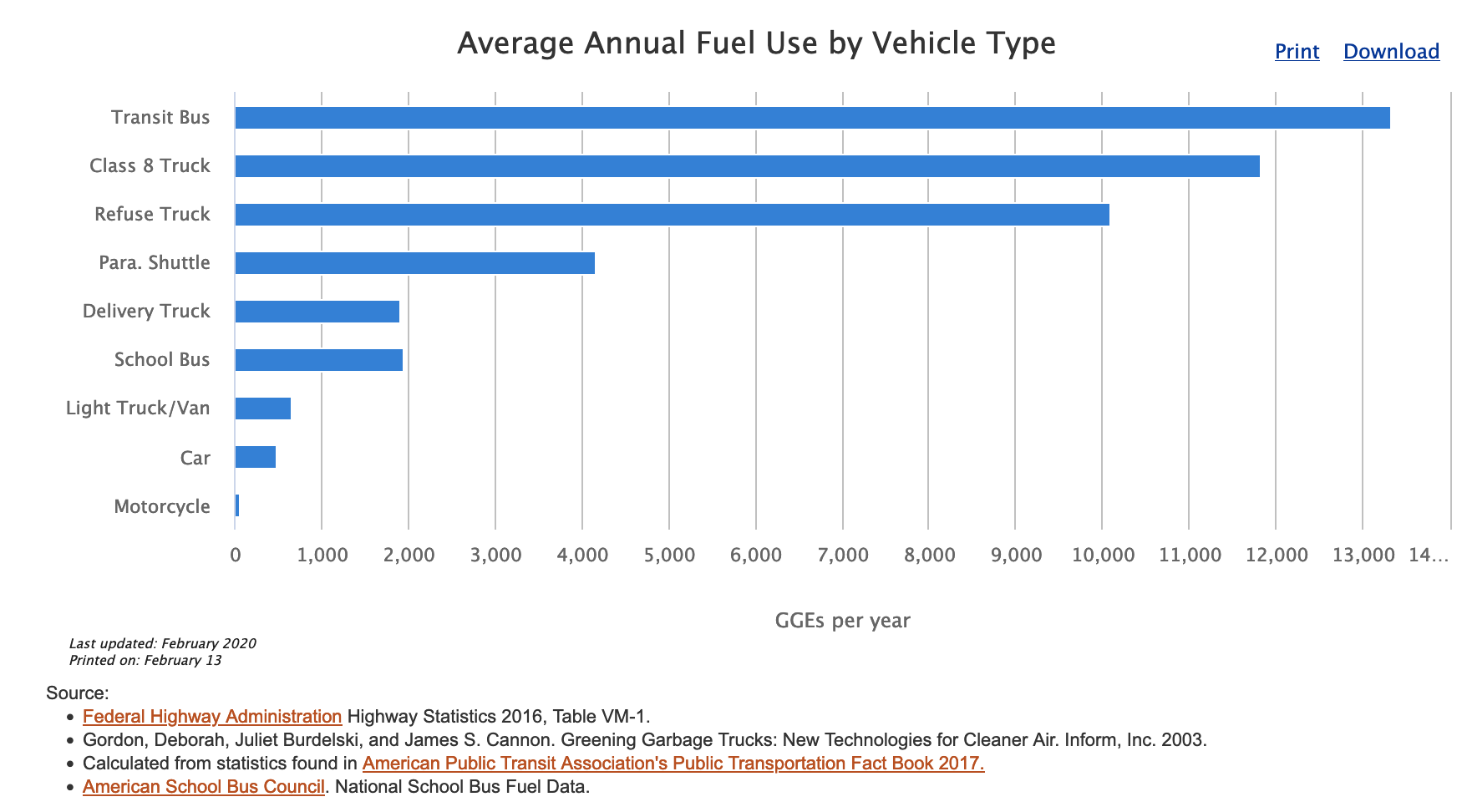

Second, gas is the most heavily consumed petroleum product in the US, at 44% of the total in 2021. I was not able to find a breakdown of consumer versus commercial/municipal use. But keep in mind the per vehicle disparity is large:

It has been widely reported that increases in gas prices to truckers has an impact on end product costs, particularly food.

Similarly, higher oil prices are regularly correlated with, and used to justify, much higher airfares.

Admittedly, the CEPR study falls back on its use of “core inflation,” derived from CPI and the personal consumption expenditures, so one can argue that it is narrowly correct in using consumer-related figures all around. But the Fed reliance on comparatively few and much jiggered key metrics is questionable.

I will ask my mavens what they think of this work.

By Alex Kimani, a veteran finance writer, investor, engineer and researcher for Safehaven.com. Originally published at OilPrice

- A new study has found that high gas prices have a much lower impact on U.S. core inflation than earlier assumed.

- U.S. inflation has been falling since mid-2022 and currently stands at a more palatable 6.5%.

- Much of the increase in inflation triggered by rising crude prices occurs in the first month after the rise in crude prices but is only short-lived.

For decades, the conventional wisdom in macroeconomics has been that high oil and gas prices are frequently the leading cause of high inflation. In fact, many analysts have blamed the two major oil price shocks of the 1970s for high inflation during the decade. The argument has been that oil prices and inflation are connected in a cause-and-effect relationship, therefore, as oil prices climb, inflation tends to follow in the same direction higher and vice-versa. This is supposedly the case because oil is a major input in the economy, and if input costs rise, so should the cost of end products.

But a new study has found that high gas prices have a much lower impact on U.S. core inflation than earlier assumed. A deep dive into the latest wave of high inflation in the United States reveals that the relationship between high energy prices and inflation is hardly straightforward nor is it supported by available data.

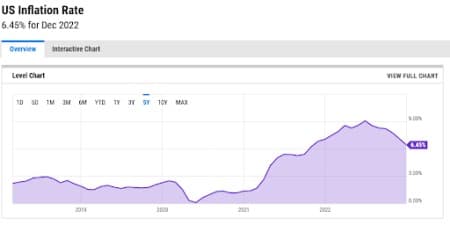

After an incessant climb to multi-decade highs, U.S. inflation has been falling since mid-2022 and currently stands at a more palatable 6.5%.

Source: Y-Charts

According to a study by the Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR), the share of motor-fuel spending in the consumer basket in the U.S. is ~4%, far less than the shares for food or shelter. Moreover, a 1% increase in the price of crude translates to a mere 0.6% increase in the price of gasoline, further lessening the impact of crude prices on inflation.

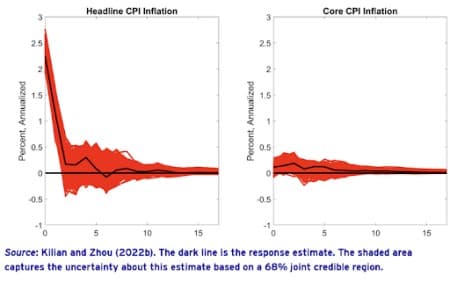

CEPR goes on to say that much of the increase in inflation triggered by rising crude prices occurs in the first month after the rise in crude prices but is only short-lived.

According to CEPR, past attempts at quantifying the inflationary effects of energy price shocks often relied on empirical methods that have been demonstrated to be invalid.

By using state-of-the-art vector autoregressive models, however, the organization has found that whereas a one-time unexpected increase in gasoline prices does cause a sharp increase in U.S. headline consumer price inflation (CPI), the response only persists for two months before becoming indistinguishable from zero.

CEPR concludes that there is no evidence of persistent increases in inflation due to rising gasoline prices or of delayed periodic inflation spikes, as wages are renegotiated.

Source: CEPR

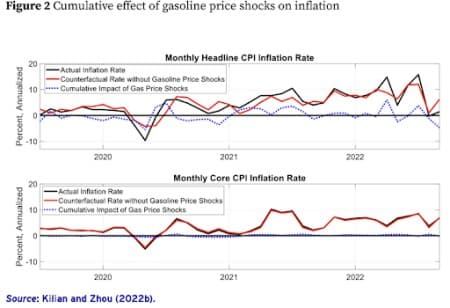

So, how would U.S. inflation have evolved after June 2019 if gas prices had remained at previously low levels? Well, CEPR has modeled this and found that inflation would only be moderately lower. For instance, in May 2022, higher gas prices added ~1.2 percentage points to the 12-month headline consumer price index inflation rate compared with an actual rate of 8.5%, an impact CEPR says can be safely ignored.

Source: CEPR

U.S. Deflation

There’s an emerging school of thought that says that economists should be more worried about possible deflation in the U.S. rather than the current inflation.

Last February, maverick stock picker Cathie Wood of ARK Invest(NYSEARCA: ARKK) told a webinar that advances in technology will likely push productivity rates higher, outweighing any gains in wages.

“We have a very strong point of view that productivity gains we will witness over the next five to 10 years will be astonishing. We think productivity will increase 5%-plus, and we won’t have an inflation problem,” she said.

Wood remains one of the few prominent fund managers who say that deflation, rather than inflation, will be a driving force in the U.S. economy and stock market over the next few years. ARK Invest has become famous for being something of a contrarian by betting on high-valuation, high-growth stocks that soared during the early stages of the pandemic.

Back in December, in an opinion piece in Politico, Dartmouth College economics professor David Blanchflower called the Fed’s reliance on interest rate hikes “guessenomics on zero data”, further predicting that a period of deflation might be the end result. EasyKnock Inc. CEO Jarred Kessler says that deflation may be at hand, telling Benzinga, “I haven’t seen real deflation in my or my parents’ lifetime, but as bad as the economy we’re looking at is, we may experience a deflationary period ahead.”

According to Kessler, government stimulus programs are to blame for the current economic woes, and people will start drawing on their home’s equity again because “there aren’t a lot of options left” after credit card debt recently surged to 18-year high.

Another jarring sign: Bloomberg says the rental markets could be deflating, with home and apartment rental markets having dropped sharply over the past 90 days while vacancies are rising.

There’s nothing palatable about 6.5% inflation. At least not for me.

No comments about the ’70s oil-induced inflation? Pre-fracking peak oil in the U.S. was in 1971. Price of a barrel (a barrel!) of oil was $1.75 in ’71, and the U.S. imported about 30% of its oil (cf. Daniel Yergin’s The Prize–a history of the industry). When the Arabs reduced production in response to the Yom Kippur war in 1973, the price quadrupled overnight, peaking in 1982 at $42/bbl–about the current price, when you adjust for inflation.

So…”money printing” was not at the root of that long decade of inflationary pressure.

Y’all might not remember ’70s inflation, but that was the incentive for the “Volcker shock” that raised the prime rate to 21% and mortgages to 16 – 18%.

Maybe the current inflation isn’t as directly tied to oil prices as it was in the ’70s, but the ’70s certainly weren’t possible without petroleum inflation.

Reagan lucked out because Alaska’s North Slope came online (and Carter deregulated natural gas, says Warren Mosler), so prices retreated to $10-$11/bbl.

My guess is this obsession with gas prices as a major cause of inflation is trauma from the oil shocks of the 70s. This also serves as cover for the real, dubious causes of inflation like inflated financial asset prices.

Researchers posting a CEPR paper — “CEPR … Europe’s leading network of Economic Policy Researchers” — “using state-of-the-art vector autoregressive models” discover that the correlation between oil prices and inflation is not straightforward. And here I thought that Europe’s leading Economic Policy Researchers might have plenty to keep them busy studying the European economies and the impacts of higher natural gas and diesel prices, and higher fertilizer prices on many European economies — impacts which promise to be broader than just inflation. However, I can understand how when compared with the inflation reported for many European economies the reputed u.s. inflation of 6.5% might seem palatable.

“CEPR concludes that there is no evidence of persistent increases in inflation due to rising gasoline prices or of delayed periodic inflation spikes, as wages are renegotiated.” Wait a minute — I thought this was a post about the correlation between oil prices and inflation. How many readers of OilPrice would seriously entertain a conjecture of a straightforward correlation between crude oil prices and the price of gasoline at the pump? Yet it appears this post is using the price of gasoline at the retail pump as a proxy for oil price inflation. And how is it that a complex commodity like oil is treated as a single entity for a discussion in a forum where many of the readers are well aware that the category oil includes many different kinds of oil affecting the crack fractions of the end products and feeder products leaving the refinery?

If there were no market consolidation, and if there were a ‘true'[funny after several searches I was unable to locate what I remember as Kenneth Arrow’s five axioms defining a Market] Market for a good such as petroleum — oil — then I would imagine a few runs of the Leontief input-output models for the u.s. economy might reveal some broad impacts between the prices of a mix of petroleum products and price increases in the u.s. economy, including some rough gauge of the time lags in those prices. However, I believe the financialized structure of the u.s. economy and the relative lack of productive industry might strangely skew inflation estimates based solely input-output relations and their impacts on prices and costs — that is — any relation between oil prices and inflation would be anything but straightforward.

I wonder who ultimately funded this little CEPR study and application of “state-of-the-art vector autoregressive models”, and I wonder what they hoped it might accomplish.

This appears to be based on this article, which is by the authors of this paper (only six quid to you squire).

The end of the abstract:

“much of the observed increase in headline inflation in 2021 and 2022 reflected non-energy price shocks.”

I don’t consider that statement controversial. The broader question is how price shocks become a trend. There must be some reinforcing feedback loops in the system. Wage-price spiral is the one the bosses love to invoke but there must be others since, as Mick Lynch has pointed out, for a wage-price spiral you need wages to go up.

Thanks for finding the reference, even so, I think I will save my six quid. This from the abstract: “Our analysis confirms that focusing on gasoline price shocks alone will underestimate the inflationary pressures emanating from the energy sector, but not enough to overturn the conclusion that much of the observed increase in headline inflation in 2021 and 2022 reflected non-energy price shocks.” [When did the u.s. embargoes of Russia get going? 2021 or 2022? And did not the Corona flu hit commerce especially hard in 2021?]

The flavor of that sentence is very different than the flavor of this post, and this post showing up in OilPrice strikes me a strange.

“There must be some reinforcing feedback loops in the system”:

Try a few shortages of key products as Globalization hits a few snags, as the Corona flu pandemic is declared over — even though it is not over, and add a little pricing power to pass on costs, exploit shortages, and ratchet up profit margins — and add in sudden shortages of a large family of commodities that serve as a crucial input to a large number of products. Even if average wages may have gone up an iota I believe the number of people in the workforce drawing wages has decreased and the growing number of cuts in the tech sector may not have played out in average wage calculations. A wage-price spiral — probably better named a price-wage spiral — seemed a ‘pretty story’ to explain the 1970s inflation. It might be interesting to study how the Fed’s interest rate increases might provide positive feedbacks to inflation.

Given my partial gathering of ways the present inflation is driven and I remain mystified to explain how “state-of-the-art vector autoregressive models” might somehow derive a “straightforward” correlation between oil prices and inflation. Is it any surprise to discover the correlation is not “straightforward”?

> A wage-price spiral — probably better named a price-wage spiral . . .

Yes, that is putting the horse in front of the wagon, however it is too much truth to be widely used.

As for Kathy Woodshed claiming productivity improvement are going to bring deflation, I think not. We now have algorithms openly being sold as collusion for moar profits to entire sectors of business and the owners of these price fixing and gouging programs will claim it is their right to innovate to trash whatever laws were in place that were never enforced for the last four decades. They will get away with it, never mind the little lawsuits victims bring.

Criminality backed by Wall Street is being served. Misery and stawk indexes, line goes up.

One lurking danger for international trade agreements is the confluence of the US falling into a deflation economy with fewer disposable consumer dollars while at the same time the BRICS are trading among themselves more successfully. This ultimately means we can’t make good offers because our country has poorer consumers and high unemployment. And at the same time the BRICS are fed up with our neocolonial trading practices which have left them destitute. We seem to be courting Latin America, probably to promise we will continue to manufacture in their countries even as we shut down more of our own factories, using inflation as an excuse. I was amazed to see Lula so friendly with Biden and to hear about new and better relations with Mexico. But as usual none of this comes together logically and is made even more illogical by the fact that we seem to be losing control over the oil trade. I don’t think this bodes well for our own employment statistics.

On the technicalities I’m a dummy, and to me it seems we will keep needing good summarizing statements on the perfect storm aspect [everything I’m writing here will have the ring of school of the un-skooled]. I look around, and there are a lot of BMWs on the road. Is BMW not affected by lack’o natural gas? Will there be no lag when the owners need parts? [and the prices??] Oh the day of reckoning.

So far cnchal and Susan the Other seem to be uttering something along the lines of what I’m thinking. Would like more light on the algorithms cnchal mentioned. With shoot-dollar-empire-sanctions and little-that’s-complex to export [not that the biosphere can or should-try-to-support production of more and more complex consumer items forever] and the Fed plus Street aiming for fewer-workers-paid-less…can prices go anywhere else but up? (we’re basically into asset stripping ourselves these days, right?)

I can only afford time to scan stuff from Dean Baker, but seems like he’s ignoring the big layoff zeitgeist. Mark Weisbrot always seemed to explain things well in days gone by [though IMO he could have broken down exchange rates and SWIFT a little more]. What happened?

When (if) this left-right coalition Hedges is talking about gets going, it might take a while, but does anyone imagine one day it won’t be a’lovin fracking all that much? Vinyl chloride in the air.

Way off topic, another New Deal. What would you name a spending bill to enable all US businesses (crazy ones or not) to hire enough workers…to bring their performance up to speed with what buyers of their products-or-services expect? I mean, you can talk greening this or greening that, but when planes can’t fly across the whole land cause the no-fly list is lost…