Readers may question why the New York Fed would publish a research paper that described a new mechanism by which the US caring only about the effects of its monetary policy on the US could have bad effects on developing economies.

At the IMF, the research arm has long been to the left of the “program” and has often issued papers which describe how austerity is counterproductive. A famous one in the early 2010s determined that in weak economies, fiscal multipliers were over one, which in layperson speak meant budget cuts would actually worsen debt to GDP ratios because the economy would contract more than the reduction in borrowing. Mind you, this key insight had little impact on how the IMF does business.

The Fed hires very bright monetary economists. While some may seek to stay at the Fed, for most, a promising career path is to land in the research arm of a big Wall Street firm or money manager. For them, publishing insightful papers is career enhancing. They also make the Fed look like more of an honest intellectual broker while being very unlikely to spur calls for change.

A long-standing criticism of the Fed’s lack of interest on the international effects of its interest moves is that hot money washes in and out of higher-risk developing economies. A group of central bankers complained to Bernanke during his 2014 taper tantrum, to no avail. As we wrote in 2015:

India’s central bank governor Raghuram Rajan took to Bloomberg to criticize the Fed for its failure to coordinate policies with the rest of the world. And Rajan can’t be dismissed as a partisan defending his country’s policies. Rajan is a Serious Economist, former IMF chief economist, and best known in popular circles for presenting a badly-received paper at Greenspan’s last Jackson Hole session that said that financial innovation was making the world riskier and could well cause a full blown financial crisis. And he assumed office only last September, so he’s also not defending policies he implemented…

Rajan is blunt by the standards of official discourse:

Some of his key points:

Emerging markets were hurt both by the easy money which flowed into their economies and made it easier to forget about the necessary reforms, the necessary fiscal actions that had to be taken, on top of the fact that emerging markets tried to support global growth by huge fiscal and monetary stimulus across the emerging markets. This easy money, which overlaid already strong fiscal stimulus from these countries. The reason emerging markets were unhappy with this easy money is “This is going to make it difficult for us to do the necessary adjustment.” And the industrial countries at this point said, “What do you want us to do, we have weak economies, we’ll do whatever we need to do. Let the money flow.”

Now when they are withdrawing that money, they are saying, “You complained when it went in. Why should you complain when it went out?” And we complain for the same reason when it goes out as when it goes in: it distorts our economies, and the money coming in made it more difficult for us to do the adjustment we need for the sustainable growth and to prepare for the money going out.

Back to the current post. In The Dollar’s Imperial Cycle, New York Fed authors Ozge Akinci, Gianluca Benigno (professor of economics at the University of Lausanne) and

Serra Pelin describe how dollar pricing of exports whipsaws emerging economies, both by making their goods less competitive and by making dollar-based financing more costly. From their article:

Behind our analysis lies a multi-polar characterization of the global economy, comprised of the United States, advanced economy countries, and emerging market economies. In our multi-country DSGE model, as in the Dominant Currency Paradigm (DCP), we assume that firms in the emerging market bloc set their export prices in dollars while firms in advanced economy countries set export prices in their own currency. A stronger dollar therefore creates a competitive disadvantage for emerging market economies. We also assume that there are financing constraints so that firms need to borrow in dollars to finance purchases of imported intermediate inputs. As we show in our model simulations, presented in a recent staff report, these two forces make dollar appreciation particularly detrimental for the manufacturing sector in emerging market economies.

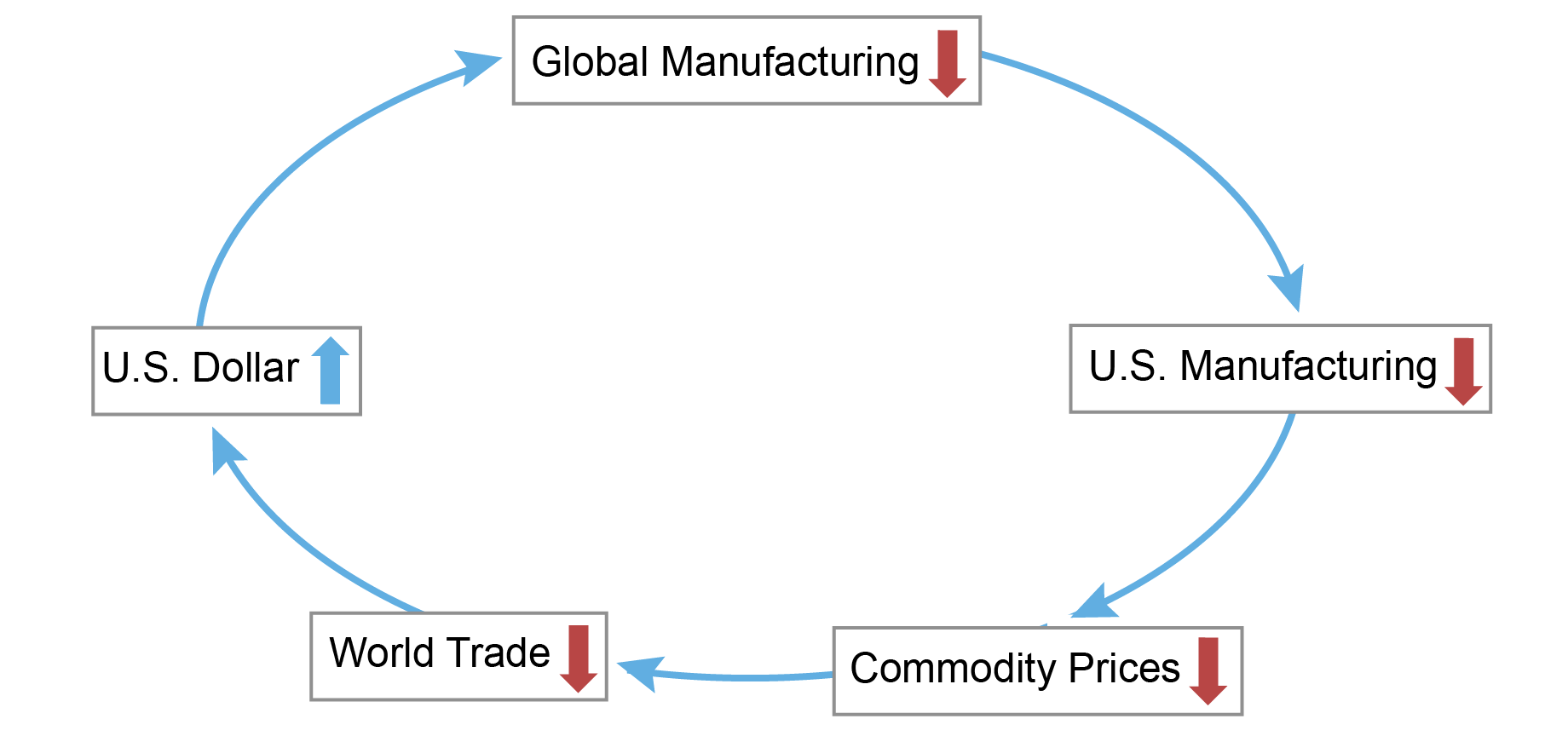

The chart below visualizes the Dollar’s Imperial Circle. A tightening of U.S. monetary policy sets the circle in motion, generating an appreciation of the dollar. Given the structural features of the global economy, tighter policy and an appreciation of the dollar lead to a contraction in manufacturing activity globally, led by a relatively larger decline in emerging market economies. The resulting contraction in global (ex-U.S.) manufacturing will spill back to the U.S. manufacturing sector due to the reduction in foreign final demand for U.S. goods. These same forces will also lead to a drop in commodity prices and world trade. In the final turn of our mechanism, given that the U.S. economy is relatively less exposed to global developments, the contraction of global manufacturing and global trade is associated with a further strengthening of the dollar, reinforcing the circle.

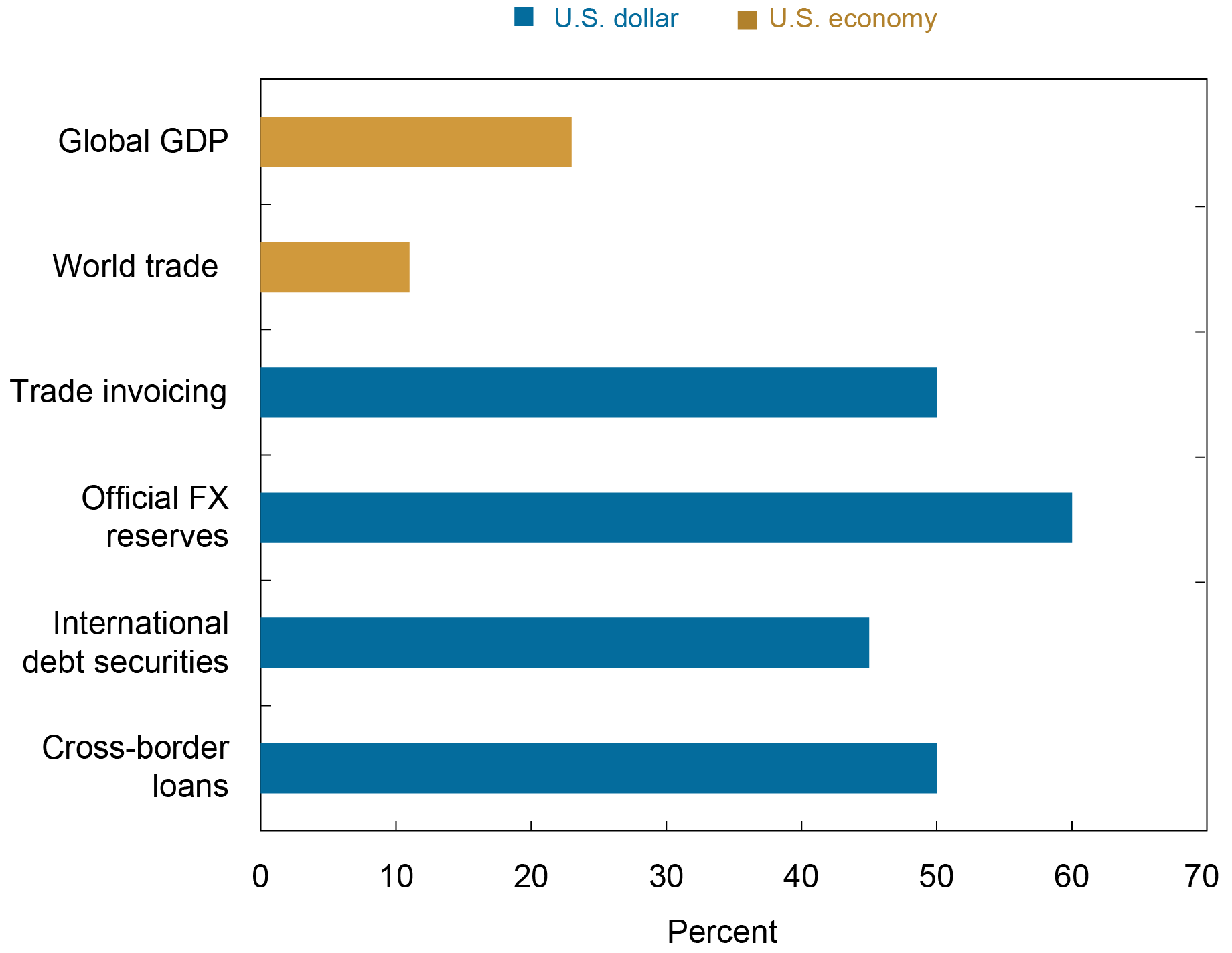

Behind the Dollar’s Imperial Circle are two key asymmetries in the structure of the international monetary system and the U.S. economy. The first asymmetry arises from the fact that global use of the dollar in the international monetary system greatly exceeds the relative size of the U.S. economy. The following chart captures this fundamental asymmetry.

…. Besides its dominant role in trade invoicing, the U.S. dollar is also the dominant currency in international banking. About 60 percent of international and foreign currency liabilities and claims are denominated in U.S. dollars (see Bertaut et al. (2021)).

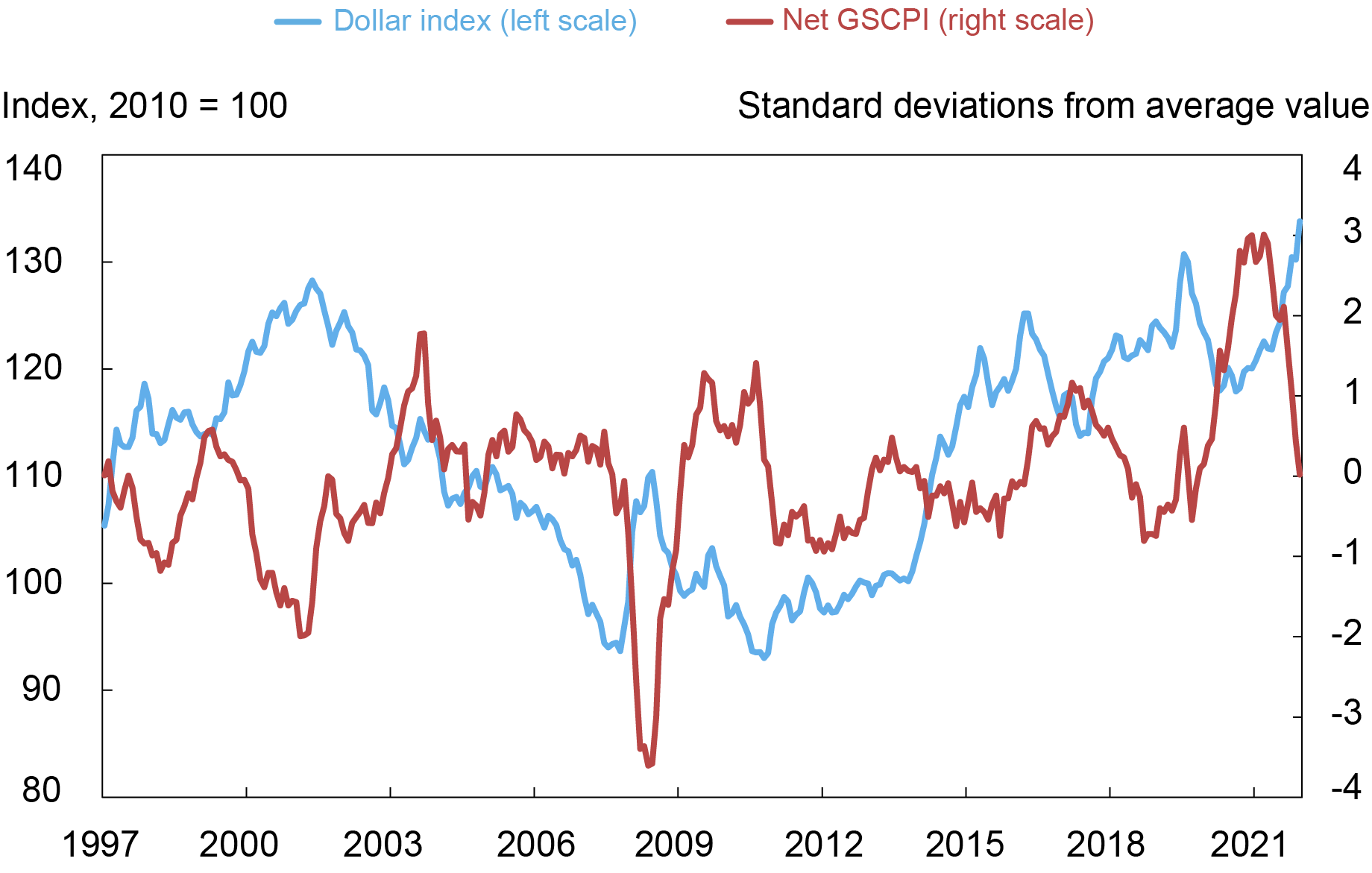

In addition, as discussed by Bruno and Shin (2021), a strong dollar tends to reduce the availability of the dollar financing needed to support supply chain linkages. As a result, movements in the dollar affect global activity through this financial channel. The chart below captures the link between the broad dollar index and global supply chain imbalances, a measure that builds upon the New York Fed’s Global Supply Chain Pressure Index (GSCPI).

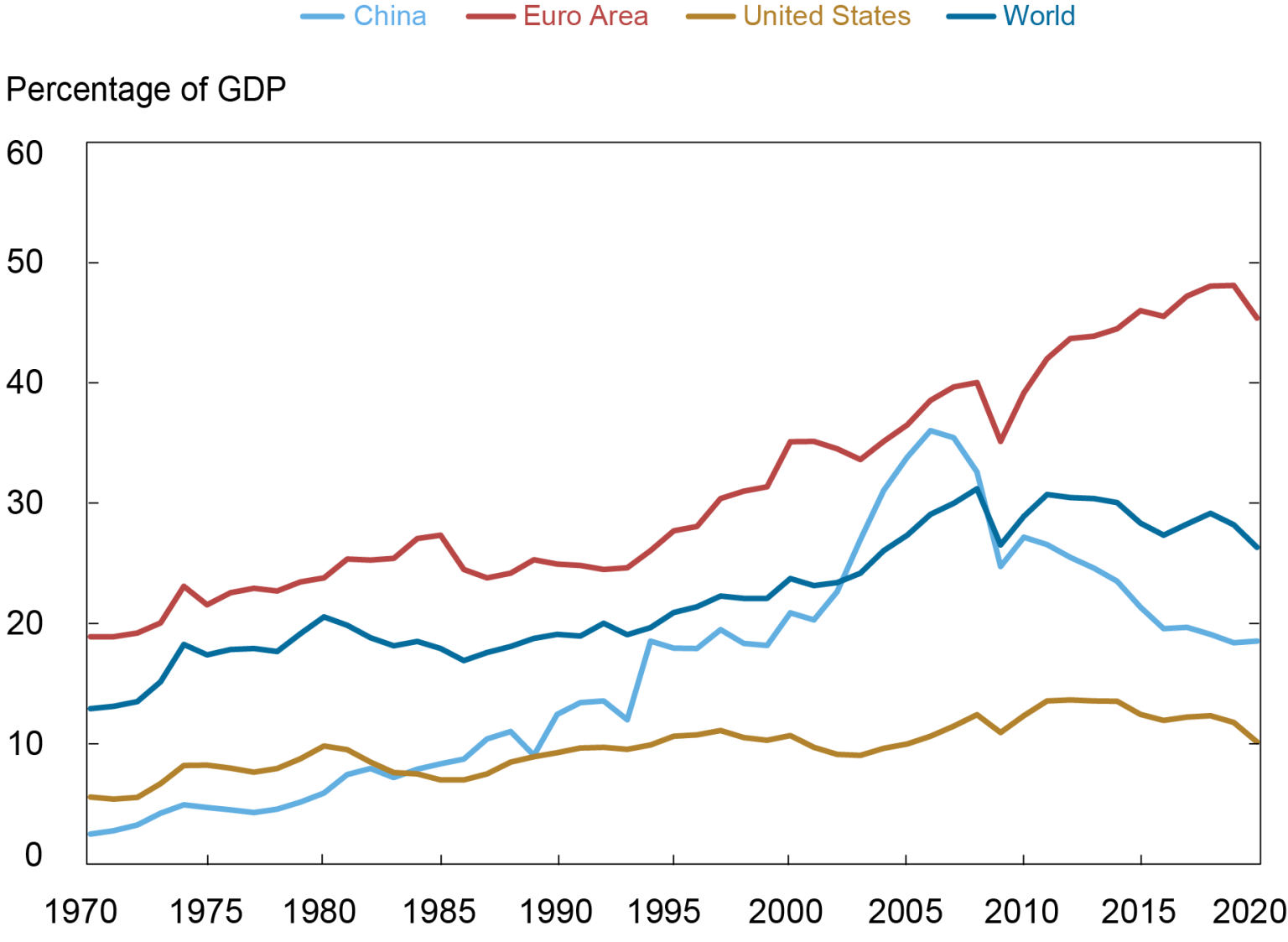

The second asymmetry occurs as the U.S. economy is less exposed to movements in global trade relative to its trading partners….

There’s more in this clever and well-presented paper, which I encourage you to read in full, but the extracts above give you the gist of the argument.

Notice that the effect of interest rate increase and dollar price movements on trade invoicing and dollar-based (as in often trade) financing is to amplify economic cycles, which increases volatility and instability. Economists call that “procyclical” which = “bad”.

The second is that even though the world has become more globalized, the US export share of GDP is low by world standards and hence we aren’t much affected even indirectly (as in by interest rate tightening whacking our export partners).

I hope you’ll send this paper around to potentially interested readers.

The conclusion of this paper is that, when the Fed tightens (raises interest rates) to fight inflation the resultant strengthening of the dollar is a pro-cyclical (i.e. amplifying) force in the global economy. We also know that if the tightening is excessive, it will be pro-cyclical in the U.S. economy (i.e. so amplifying it leads to a “hard landing”).

It also says that both US and global economic activity and trade declines when interest rates go up and the dollar strengthens. We know that this has an unfair distributional impact in the US as it falls relatively greater on poorer and more marginally employed citizens. With this paper, we also know it has a similar global impact as it falls relatively greater on poorer countries.

What the Fed seems to want from higher interest rates is demand suppression (and lower inflation) domestically. What this paper indicates is that it also leads to supply suppression globally (especially in manufactured goods and perhaps commodities as well). The two tend to work against eachother in the fight against inflation.

The paper implicitly raises the question of who benefits and whether these justify the costs.

Perhaps an implication is that interest rates — the single “dial” the Fed turns to deal with inflation — may entail too many undesireable side-effects to be a reliable tool. Certainly, the pro-cyclical aspect can lead to “harder landings” and/or more market volatility than the Fed intends.

And, it looks like this problem will only get worse. There seems to be little prospect that the dollar’s dominance in trade will lessen. In fact, imho, it stands to keep increasing.

So, dumb question: Does the interest rate imposed ostensibly to bring down inflation actually cause the inflation to be transferred to the imperial currency rather than to commodities and thereby perpetually maintaining a beneficial exchange rate for the dollar as world economies expand? So is it treading water because the re-valuation (?) of the dollar creates the re-inflation of commodity prices? Until?

I’m not quite sure what you’re getting at. Can you clarify what you mean by “inflation being transferred to a currency”?

In any case, I suspect the answer is “both/and”, i.e., the Fed’s hiking U.S. interest rates has effects on both the dollar’s exchange rate against other currencies and on commodity prices. But the balance between the two effects is probably the subject of a thousand Economics dissertations.

The main point is; when the US (FED) raises interest rates to, supposedly, control inflation in the US is causes inflation in the developing countries. Most of the developing countries are heavily in debt to the World Bank and/or The IMF. The loans are denominated in US dollars. Interest payments on the loans must be made in dollars. So, countries must exchange their national currency for dollars. When the FED raises the interest rate, it causes an increase the value of dollars. So the developing see a drop in the in the exchange value of their currencies. This causes local inflation in the local currency. Because more of the local currency is required to by foreign goods and pay interest payment on the loans. So the most developing countries just print more money and the drive up local costs (i.e. inflation).

This article does not mention IMF debt. Many countries do not have it after the Asia Shock. They ended their programs and are not going back.

This table shows IMF programs. Most have 0 disbursements, which looks like they could but haven’t taken $. No one in SE Asia is listed. Neither is India:

https://www.imf.org/external/np/fin/tad/balmov2.aspx?type=TOTAL

And the IMF uses SDRs, and the dollar is only one of its five basket currencies. They did use euros for all the EU post crisis bailouts, so not sure what drives their practice. But point is they are not limited to dollars.

The exports are denominated in dollars. I assume the issue is trade financing, which would also be in dollars, like financial letters of credit.

Thank you for the reply. From the link data, things are very interesting. There seems to be a very significant change going on. I pulled some of the South American counties data up and it also is interesting. Russia and China are doing a lot of trade in local currency exchanges. This bypasses the dollar. I have an acquaintance, that does a lot waste to energy systems in Africa. From his observations of being over there, there seems to be a definite push to avoid using the dollar when possible. Dr. Hudson’s analysis on the coming demise of the dollar as the only reserve currency may be is coming sooner than expected.

We pointed out earlier that not invoicing in $ does not eliminate use of the dollar, although it could reduce some of the bad effects cited in this paper. Again SE Asian countries trade with each other and invoice in their own currencies. but their central banks flatten any imbalances via the dollar every couple of months.

The interaction between interest rates and exchange rates are always a trippy one.

Australia’s not a developing economy, but it’s also getting hammered by the US Fed’s interest rate rises.

In the US, I understand that home loans are fixed for 30 years, so increasing interest rates only affect new borrowers. Over here, almost nobody is on a fixed rate. So when the Australian Reserve Bank lifts interest rates to keep up with the US (to avoid our currency dropping against the $US and making everything more expensive), every mortgage holder in the country is affected.

House prices are down at least 10% over the last year, and it’s not stopping soon. The US Fed has managed to pop Australia’s 30-year property bubble.