Yves here. Even with the business press awash with post mortems of the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (SBV) and editorial comment about the de facto extension of a deposit guarantee to formerly uninsured depositors (the combo of changes in discount window terms and the one-year facility get you there), some key facts are still not getting enough attention. Satyajit Das underscores quite a few in his broad-reaching but compact article below.

One is that SVB had a very high ratio of uninsured deposits to insured deposits. Small deposits are considered good because they are “sticky”. Big deposits are hot money. Banks with a lot of hot money should be conservative and mindful of liquidity risk. SVB clearly was not.

Second is that SVB had several other fairly easy measures it could have taken to considerably mitigate the mess it was in with having so much long-dated bond exposure. Das cites rumors that one of those routes may have been blocked by competitors.

A related third point is why didn’t SVB get out of the way of Fed tightening? The central bank knows it whacks banks. It has therefore taken to telegraph its intentions well in advance so they can get out of harm’s way. Why did SVB remain dug in on a highly exposed strategy?

Finally, as Das delineates, the contagion effects go well beyond US banks.

I hope you’ll read Das’ piece carefully.

By Satyajit Das, a former banker and author of numerous works on derivatives and several general titles: Traders, Guns & Money: Knowns and Unknowns in the Dazzling World of Derivatives (2006 and 2010), Extreme Money: The Masters of the Universe and the Cult of Risk (2011), A Banquet of Consequences RELOADED (2021) and Fortune’s Fool: Australia’s Choices (2022)

The dominoes are, predictably, beginning to topple. In 2022, there was the crypto-crash, the UK gilt problems which triggered issues for pension funds’ liability driven investing strategies and the still ongoing emerging market debt crisis. The latest chapter in this unwinding, which has some way to go, is the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (“SVB”) in the US.

Underlying these developments is the reversal of a 13-year period of low or zero interest rates and highly accommodative liquidity policies of central banks globally. An economic architecture built around artificially low cost of capital which over-stimulated segments of the economy and encouraged leverage and speculation, on a large scale, was neither sustainable nor costless. The assumption that raising rates and withdrawing monetary stimulus would result in a painless adjustment back to a new normal was naïve in the extreme.

As Charles MacKay wrote in Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds: “Nations, like individuals, cannot become desperate gamblers with impunity. Punishment is sure to overtake them sooner or later.” Unfortunately, the financial reckoning under way will create winners and losers as well as suffering.

Silicon Valley’s Best and the Brightest

On Friday 10th March 2023, SVB was taken into administration by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (“FDIC”). The Bank, which had around $200 billion in assets, was the second largest US bank failure after Washington Mutual which collapsed in 2008. Bank failures in the US have been relatively rare in recent years with the last FDIC insured bank closing in October 2020.

The information available suggests that the collapse resulted from a confluence of events:

- SVB invested depositors’ fund in highly rated, long duration US Treasuries and Federal Agency backed Mortgage Backed Securities (“MBS”).

- These investments, which are of high credit quality, have lost value due to sharp increases in interest rates leading to unrealised losses estimated at around $15 billion.

- Concern about these losses led to a bank run with depositors withdrawing funds, culminating in $42 billion of withdrawals (around a quarter of all deposits) on Thursday 9th March 2023.

- The withdrawals left SBV potentially insolvent and incapable of paying its obligations as they come due.

The chronology of the collapse is murky.

There are suggestions that SVB sought to protect their portfolio of interest rate sensitive assets by selling around $20 billion of longer term securities and investing the proceeds in shorter dated instruments. This realised a loss of $1.8 billion but would have boosted interest earning due to the fact that the yield curve is inverse with short rates offering higher returns.

Simultaneous to the portfolio restructuring, SVB sought to raise new capital – $1.25 billion in shares and $500 million mandatory convertible preferred shares – to cover the losses on the sales of securities and also strengthen the balance sheet and liquidity. The fund raising was abandoned.

An additional factor was the highly concentrated SBV’s customer base which was heavily focused around US West Coast technology and bio-technology start-ups. It is alleged that as SVB’s problems intensified a number of venture capital firms and luminaries advised firms that they had invested in to withdraw their deposits from SVB deepening their liquidity problems. It seem that the technologically advanced adhered to the age old adage ““if you’re going to panic, panic first.”

Old Ways

SVB’s collapse can be attributed to familiar and avoidable banking risks – asset-liability mismatches and concentration risk.

All financial intermediation involves maturity transformation. Banks take short term deposits but invest these funds in longer term loans or securities. This makes them vulnerable to a rapid loss of deposits which exposes them to the liquidity and price risk of realising assets. Abnormal concentration of depositors or borrowers creates exposure to withdrawal of funding or default on assets or investments with resulting liquidity or solvency issues.

In SVB’s case, both these factors coincided. Broader environmental considerations compounded these problems.

SVB’s business model focused on venture capital and start-ups. It acted as the banker of choice for these businesses. Venture capital investors encouraged firms that they invested in to bank with SVB. Funds raised and surplus cash was parked with the Bank allowing investors to keep a close eye on operations. These start-ups frequently also took out credit facilities from SVB a condition of which was that surplus cash had to be deposited with them In addition, employees frequently also banked with SVB and took out loans. Its success was in no small measure due to the fact that traditional banks were less willing to offer financial services to these nascent companies.

SVB’s business underwent rapid expansion over the last few years as funds flowed into private markets and the volume of venture capital, start-up and early or late stage funding grew. The Bank’s liabilities appear to be dominated by a small, group of depositors. As at end of 2022, over 80% of the bank’s $173 billion in deposits were uninsured being over the FDIC maximum of $250,000.

At the same time, highly accommodative monetary policy meant that the financial system was awash with liquidity. The problem became larger during the pandemic when lockdowns and supply shortages drove a rapid increase in savings rates adding to the liquidity of the banking system. Between Q4 2019 and the first quarter of 2022, deposits at US banks rose by $5.4 trillion.

Normally, this liquidity would be deployed as loans. However, since the 2008/2009 Great Recession, loan demand has been relatively weak and well below deposit growth. Between Q4 2019 and the first quarter of 2022, only 10-15% of deposits growth at US banks was lent out. Banks had to seek out alternative investments.

During this period, banks invested deposits surplus to loan demand in securities, mostly US government bonds or high quality MBS. Since the pandemic, banks have increased their holding of over $4 trillion in securities investments by around 50 per cent.

The choice of securities was designed to minimise credit risk. However, with interest rates low, banks took on duration or interest rate risk, extended the maturity of securities. The higher return on these long dated securities boosted bank profits.

SVB followed this formula. Its assets rose by around 250% + over three years as rising capital investment in start-ups was deposited at the bank. SVB invested this cash in longer-maturity bonds to generate a higher return. By end 2022, it held around $120 billion in securities.

Beginning in 2022, a change in conditions affected these practices.

Responding to higher inflation, central banks globally led by the US Federal Reserve began to aggressively increase interest rates. At the same time, they commenced QT (quantitative tightening) gradually removing liquidity by decreasing the size of their balance sheets by reducing bond purchases and then allowing existing holdings to run off. The combined effect of these actions was to shift interest rates up across the entire yield curve.

Higher interest rates decreased the market value of these fixed interest securities. In the case of MBS, the losses were compounded by convexity effects. When interest rates increase, mortgage prepayments decline meaning that the term of the security extends increasing duration and the losses. SBV had unrealised losses of $15 billion as at end 2022.

However, these mark-to-market paper losses would not be realised unless the securities were to be sold. Unfortunately, the decline in prices coincided with declines in cash inflows into banks and rising withdrawals reflecting lower savings as post-pandemic spending increased and prices rose especially for essential goods and services.

SVB was also affected by the altered environment for venture capital and start-ups. Weakening equity markets led to decreases in Initial Public Offerings (“IPOs”) and the end of the boom in Special Purpose Acquisition Corporations (“SPACs”) reducing exit opportunities for investors. This reduced new investment in private companies. With limited new funding and a high rate of cash burn, start-ups started to use up their funds drawing on their SVB’s deposits. As the rate of outflows increased, the Bank’s asset liability mismatch became problematic necessitating sales of holding realising the mark-to-market losses eroding their capital base.

The puzzling thing is why SVB did not pursue several avenues available to manage its evolving risks.

Given that the credit quality of its securities was high and they would pay back in full if held to maturity, it would have been open to SVB to used them as collateral to borrow funds, through the repo market or from the central bank, to meet deposit withdrawals. Lender-of-last resort facilities provided by central banks are specifically available to meet these contingencies.

Alternatively, they could have borrowed in the wholesale or interbank market to replace deposits to bridge the cash outflows. There are unsubstantiated allegations that alongside prominent venture capitalists who advised their start-ups to withdraw money, a number of large banks withheld inter-bank loans from SVB and actively sought to convince SVB customers to move their accounts. If true, then the active solicitation of deposits by competitors could have worsened the deposit flight accelerating SVB’s problems.

Spread

US regulators have been anxious to state the low risk of contagion and the overall strength of the banking system. After all, in June 2017, then Chairman of the Federal Reserve Janet Yellen told a London audience that the banking system had been made safer and a new financial crisis in our lifetimes was unlikely.

However, there are several channels of potential contagion both in the real and financial economy.

Firms with deposits at SVB are at risk. Many of these start-ups have no revenue and without access to their cash cannot operate, including paying employees and suppliers. Reports suggest that over 80% of customers deposits (around $150 billion) were over the FDIC threshold of $250,000 and therefore uninsured. Given that SVB senior and subordinated bonds are trading at 45% and 12.5% of face value, uninsured depositors may face significant losses in the absence of government intervention or new owners injecting substantial capital into the Bank.

Loss of their funds may force some start-ups into bankruptcy or, in the case of more established operations, to retrench operations. In addition, SVB is the provider of credit facilities to the private capital industry and the withdrawal of this funding would create an investment shortage.

Even those with no relationship to SVB could have experienced indirect effects. Many external payroll providers use the bank for payments and funds are now trapped. According to legal experts, under California law, founders and individual executives can be personally liable for unpaid wages under certain circumstances complicating the situation.

The collapse of SVB may be widely felt across the technology sector and affect economic activity more broadly.

The financial effects are less predictable. Circle, which operates a crypto-stable coin, has announced that it has $3.3 billion of its reserves with SVB, triggering a fall in the value of its token as the crypto market. However, there is no evidence to date that SVB has interbank and derivative transactions with other market participants, at least of a magnitude, to trigger a major contagion event.

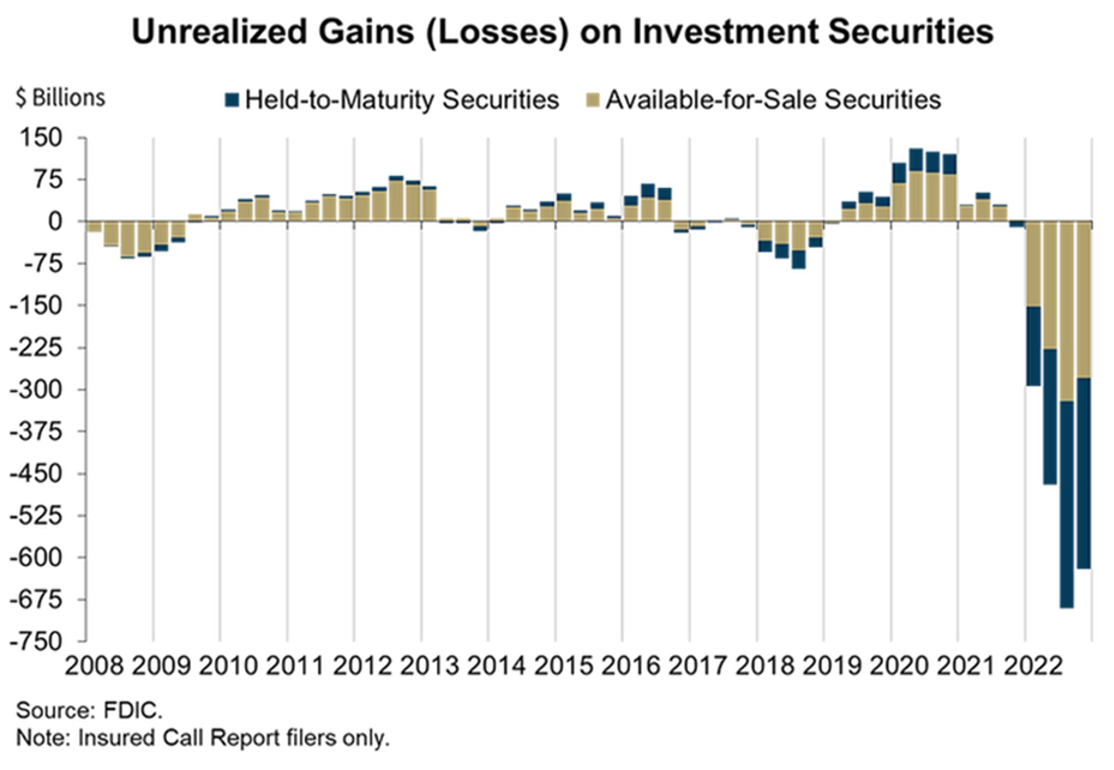

There is concern that the broader issues behind the problems of SVB – falling customer deposits (projected to decline in the US by up to 5% this year) and losses on holding of securities- are systemic and pervasive across the banking sector. Estimates suggest that the unrealised losses at FDIC insured US banks exceed $600 billion as at end 2022. The losses globally are perhaps 3 to 4 times that number.

While individual exposures vary significantly, for major systemically important money centre banks, realisation of these mark-to-market losses while significant should not affect solvency. Nevertheless, concern has triggered sharp declines in bank share prices across the world, especially in US regional institutions, some of which have lost a large part of their value.

Subsequently, FDIC took over Signature Bank, whose shares had fallen 30% while trading in some other firms were suspended because of extreme volatility of their stock prices. One issue is the lack of information of the extent of the problem. However, this issue will be in focus now and, it is conceivable, that there will be other casualties.

The problem is not confined to commercial banks with central banks also affected. Given that since the Great Recession, global central banks have greatly expanded their holdings of securities (estimated at over $30 trillion). The mark-to-market losses (from rising interest rates) on these portfolios are in the order of $3-5 trillion far exceeding their capital. The US Federal Reserve bond holdings have fallen by as much as $1.3 trillion. The eurozone has also incurred large losses.

The problems of central banks are exacerbated by their bond purchases as part of their long-lasting quantitative easing (QE) programs. Central banks purchased long term securities by creating overnight bank reserves. Currently, the interest cost of servicing the reserves has risen sharply while the value of bond holdings have fallen sharply reducing income and decreasing their shareholders’ fund.

While technically central banks cannot go bankrupt, negative equity can reduce market confidence in the currency or sovereign credit.

There is also an effect on public finances as central banks remit their net income to state treasuries. This revenue reduces budget deficits and borrowing needs. Before 2008, remittances from the Federal Reserve averaged $20-25 billion per year increasing to more than $100 billion as the balance sheet grew. These are likely now to be much lower and possible zero.

The contagion effects are also dependent on potential actions by authorities. Long term interest rates may experience upward pressure if holders choose or are forced to liquidate portfolios. During the September 2022 problems in the UK government bond market, the Bank of England instigated a mini-QE program to provide liquidity and stabilise yields. Any dislocation in bond market liquidity, already fragile, and volatility in yields risks disruption of the economy.

The working assumption is that these securities will be held to maturity and pay out their face value in full meaning that the losses will never be realised and ultimately disappear. This may prove to be correct but cannot be guaranteed.

An additional concern is the effect on Federal Reserve interest rate policy which influences global rate settings. If monetary policy is loosened to alleviate the risk of financial instability, then inflationary expectations may become entrenched and price rises accelerate. This would create a different economic and financial problems.

While SVB’s failure may not be of immediate systemic import, a combination of the different factors set out above could be highly damaging. Any judgement on the risk of contagion may be premature.

Resilience

Regulators have been quick to state that the financial system is far more resilient than in 2008 due to strengthening of regulations. While that may be partially true, the case of SVB highlights major loopholes and deficiencies.

One potential problem revealed is in regard to liquidity. After 2008, banks were required to always keep adequate liquid funds to meet depositor obligations. There were two specific rules. The Liquidity Coverage Ratio (“LCR”) required banks to hold high quality liquid assets, cash or short-dated government securities, covering estimated cash over 30 days. The complementary Net Stable Funding Ratio (“NSFR”) emphasised higher reliance on more stable or ‘sticky’ retail deposit rather than wholesale or inter-bank funding.

While the LCR and NSFR regulations mandated by the Bank of International Settlements (“BIS”).popularly known as the Basel rules, were adopted by the US, it did not apply to SVB because it did not meet the threshold of a systemically important banks and relied on corporate deposits rather than short term wholesale funding.

A second problem relates to the valuation of holdings of long term securities. SVB followed accounting guidelines which did not require it to mark-to-market its portfolio. This is because the bulk of its holding were in hold-to-maturity (“HTM”) (which are valued at amortised cost) rather than available for sale (“AFS”) portfolios (which are valued at market prices). If SVB’s portfolio had been properly valued, as at end 2022, its shareholder funds of $16 billion would have been substantially reduced by the $15 billion of unrealised losses.

The rationale for permitting HTM securities to be held at amortised cost rather than current value is unclear. As SVB and previous similar episodes illustrate, transitory losses assume that the holdings do not need to be liquidated to meet, for example, withdrawal of deposits resulting in unrealised losses being realised with immediate impact on solvency.

SVB also highlights other weaknesses in bank regulation:

- The Basel rules are not uniformly applied globally with national regulators adjusting standards for domestic and political purposes reducing their effectiveness. In many countries, such as the US, multiple regulators, Federal and State, frequently dilute regulations.

- Existing rules apply more rigorous rules to large systemically important institutions. In reality, smaller and regionally focused banks face significant concentration risks on both assets and liabilities (although SVB is probably an extreme case) and more limited access to capital. This has implication on their risk.

- The advantages of reliance on non-wholesale funding are exaggerated. As SVB and other cases highlight, retail and corporate depositors are likely to be less informed and are behave as a herd triggering runs on banks.

- Capital charges on high quality government securities, for example to provide emergency short term liquidity, underestimates the price risk especially at a time when the quality of sovereigns is deteriorating.

As Lord Voldemort observed in Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Part 2: “They never learn. Such a pity”.

The B Word

US regulators have been carefully to rule out a bailout aware of public distaste for such actions. However, authorities are moving to implement measures indistinguishable from the dreaded ‘B’ word:

- US President Joseph Biden and Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen have not ruled out safeguarding all uninsured deposits at SVB and presumably any other bank to prevent a run on US financial system. If this is implemented then it would mean that the state would be assuming a contingent liability in the order of $20 trillion being the total of US bank deposits.

- The Federal Reserve eased the terms of banks’ access to its discount window, allowing firms to use assets that have lost value to raise cash to avoid the outcome at SVB.

- The Fed has also unveiled a new $25 billion facility – the Bank Term Funding Program (“BTFP”)- to provide loans of up to 1-year to banks, savings associations, credit unions, and other eligible depository institutions against security of U.S. Treasuries, agency debt and mortgage-backed securities, and other qualifying assets as collateral. Unusually, these assets will be valued at par, not as usual at market value, ignoring the unrealised net losses. In effect, the Fed will be lending $100 against securities worth say $80 at current market prices – an interesting loan-to-value ratio.

- The UK government considered instituting measures designed to keep cash flowing to tech groups. One option was to provide guarantees for banks to offer new loans to companies with money locked in SVB accounts. Ultimately, this proved unnecessary as HSBC took over the operation of SVB’s UK operations which were solvent.

Policymakers argue that taxpayers are not exposed to any losses with shareholders and certain unsecured debtholders forced to absorb losses. Nevertheless, why the blanket guarantee of deposits does not entail exposure is not clear? In the US, officials floated the idea that any shortfall would be covered by a levy on the rest of the banking industry. If this were to be the case, then in practical terms banks would treat this is an operating cost, all or part of which would be passed on to customers.

The measures are inconsistent with the contained nature of the SVB problem and the adequacy of existing regulations. There are suggestions Janet Yellen, US Treasury secretary, had invoked a “systemic risk exception” to justify the measures.

Like Humpty Dumpty, regulators take the view that words mean “just what they choose it to mean—neither more nor less”.

Amusingly, Silicon Valley’s famed libertarians who resist any form of government regulation are pleading for action to prevent an “extinction event”. Some 3,500 CEOs and founders representing some 220,000 workers signed a petition started by Y Combinator appealing directly to the US Treasury Secretary to backstop depositors, warning that more than 100,000 jobs could be at risk.

The moral hazards around bailouts are well known. It seems now that tech start-ups like banks, auto businesses and anybody with an effective lobbyists are too big to fail even if they are too difficult to understand or to properly manage. As Herbert Spencer put it: “The ultimate result of shielding men from the effects of folly, is to fill the world with fools.”

Over the last decade and a half, the economic system and financial practices have become geared around low rates, abundant liquidity and the authorities underwriting risk taking. Moving away from this state of affairs was never going to easy, that is, if it is possible at all.

© 2023 Satyajit Das All Rights Reserved

An earlier version of this piece was published in the Indian Express.

There are no atheists in foxholes or libertarians in an economic crisis that directly impacts them (and specifically might bust a few business notions these libertarians hold near and dear). One of the above statements brings to mind the well done Margin Call, the board room scene where they all meet in the dead of night and decide to just sell all their lousy holdings that business day.

While I vehemently disagree with this bailout, which despite a few protestations does precisely that, it seems any broad concerns about moral hazard was mostly unlearned during the past 15 years and after Dodd Frank passed. Bank and also credit union regulators still need to keep one key aspect in mind, no one else will sing your praise if all goes well and you do the job exactly as intended. Added thought, people just get spooked and rightly so by untimely news about their deposits, always and forever.

Our local banks (First Hawaiian, Bank of Hawaii, and Central Pacific Bank) have all taken major stock price hits since the 9th.

Apparently it helps to have someone like Barney Frank on your board, but in the end it won’t save your rear-end.

Not my expertise, but doesn’t the problem of moral hazard created by low interest rates really date to Greenspan’s ‘01-‘03 rate cuts in reaction to the dot-bomb crash, Enron and WorldCom frauds, Bush tax cuts, and the September 11 attack?

Das seems to date this easy money/bad bet cycle to ZIRP in 2010, but Greenspan’s rate cuts might have as well been zero and led to the same sort of bad securities bets by outsider bankers going sour when the Fed tried to inch rates back up in ‘05-‘08 and ‘17-‘20.

Like at every other casino, the house always wins — these policies have hugely benefited the few hundred billionaires who got bailed-out by paying-off the politicals and immiserated everyone else through under/un-employment and foreclosure/eviction.

An effectively unregulated banking system can’t function in a market offering zero return. It’s Groundhog Day. Greenspan is the devil.

Yes, the problem ultimately originates with the so-called Greenspan (and then Bernanke and then Yellen) put. But it started even earlier, in 1996. Greenspan made his famed “irrational exuberance” remark and the Dow fell 143 points. Greenspan immediately lost his nerve about taking some air about what even back then was an obvious bubble.

Yes! The IPO bubble of the 1990’s was “free money” that people were making leverage bets on, just like the post-‘01 low/no interest rates. Irrational Exuberance exploited the same “it’ll be different this time” casino psychology of betting the farm on froth.

The “lesson” of the preceding S&L Crisis was to bribe Congress to repeal New Deal bank regulation and to foster Clintonian Elite Impunity: Rules for Thee, Not for Me.

“One-Trick Pony Casino”

Has a ring to it. Sounds like the name of a casino that should be in Vegas or some other Western town.

So the bank made risky bets that didnt pan out – BAIL OUT

But student loan holders, which student loans are borderline predatory lending, seeking some relief – You made those decision, live with them!

Why do only the middle/lower class have to live with their decisions? The ruling class doesn’t ever seem to have to live with theirs.

He who has the gold makes the rules.

Education debt is like medical debt. It should not be allowed in a modern society. Both education and health care should be obligations of society. It is a moral transgression of society and frivolous politics that this sort of debt burdens individual people. The banking crisis by comparison is almost funny. But banking also needs to get a clue because money itself is trust and we’ve been unable to maintain it.

Different spanks for different ranks.

Where Janet Yellen’s comment is concerned, I note with considerable distaste Carl Schmitt’s observation, “sovereign is he who decides on the exception.”

All illusions that America is not functionally a technocracy ought to thus be dispelled …

Perhaps we need to amend one of Lambert’s Rules of Neo-liberalism, from “Go Die!” to “Eat S*^# and Go Die!”

It was always apparent that SVB would be bailed-out. After all, the tech bros are mostly Team Blue supporters and contributors. I believe there’s an election coming up in 2024 where the Dems will need Silicon Valley’s support to retain the White House.

There is no sense of irony in their attitude that, while cutting emplyment is the Fed’s way of ‘bringing inflation down,’ and thousands of tech jobs are already being cut, they are crying about 100,000 jobs. Not willing to ‘take one for the team.’ LOL. They are really “special” all right.

Excellent article. Thanks for posting.

Another non-bank question: are pension funds’ assets or insurance company assets getting hammered by the same quick rise in interest rates? This is a question for another day.

So has anyone explained why SVB did not take advantage of the Fed’s LOLR facilities? Das points out that it’s puzzling, but offers no possible reasons for this lack of action. What’s up?

There’s this from Fortune magazine. No idea if it materially impacted the risk department’s activities or direction in the interim.

Silicon Valley Bank had no official chief risk officer for 8 months while the VC market was spiraling

https://fortune.com/2023/03/10/silicon-valley-bank-chief-risk-officer/

Wow! Just like FTX!

How long did SVB leave the position of Risk Management Officer unfilled again? Eight months? I guess having a ‘negative thinker’ like that around was ‘bad for business.’

Nice summary, thank you Satyajit Das.

At the same time, highly accommodative monetary policy meant that the financial system was awash with liquidity. The problem became larger during the pandemic when lockdowns and supply shortages drove a rapid increase in savings rates adding to the liquidity of the banking system. Between Q4 2019 and the first quarter of 2022, deposits at US banks rose by $5.4 trillion.

So, translation into non-financial expert speak:

‘highly accomodative monetary policy’ = government is literally giving cash away, by charging zero interest (but only to rich people/corporations; the rest of you pay 18%!)

‘the financial system was awash with liquidity’ = oodles of cash everywhere (except in the pockets of workers.)

‘lockdowns and supply shortages’ = lots of jobs disappeared, workers were laid off, stuff was not produced, or transported. No toilet paper was to be had in the Land.

‘rapid increase in the savings rate adding to the liquidity of the banking system’ = entities who had money (rich people and/or corporations) accumulated more money and deposited it in their banks. (Gee, where was all this cash coming from?) Because no one could figure out what else to do with it. Besides, China was making all our stuff. Even if all the stuff was stuck in 35 cargo ships moored off the Port of LA/Long Beach.

‘Between Q4 2019 and the first quarter of 2022, deposits at US banks rose by $5.4 trillion.’ 2 years. 2020 and 2021. $5,400,000,000,000 accumulation. Not bad.

So, the banks became, like regional Smaugs. That’s the Lord of the Rings dragon, splayed upon his pile of gold and treasure under the mountain, leaving only for occasional forays to terrorize the villagers and demand more tribute, like ‘I am now imposing a late fee for delayed delivery of Virgins.’

All that money …. crying out for useful work. Nope, nothing that needs fixing around here. Let’s buy some long term Treasuries and park these babies with the Federal government.

Could someone please explain to me clearly why having depositors lose their money improves anything. It does not make any sense to me: the main function of a bank is to keep one’s money safe. If it doesn’t do that, one should just as well keep it under one’s mattress. If one’s house had a lock that only worked on Tuesdays, that would be a bad lock, and one would replace it with something else. One wouldn’t care whether there are technical reasons for it not working.

I also don’t understand how depositors losing their money reduces moral hazard since they don’t get to see every financial move the bank makes? Do people really believe that every company, however small, should be scrutinizing every financial move made by their bank? How many “risk officers” would that require, and who would do any real work?

(It seems to me that shareholders are a different story: they know shares go up and down. They’re buying a part of the company, not making a deposit.)

I know that banks play dubious games under the covers (e.g. fractional lending) but it seems to me that it’s in everyone’s interest for the consequences of these games not to spread to the real economy since the whole point of money we all trust is to reduce the cost of transactions. Otherwise we could just go back to barter. Maintaining this trust is why governments need to regulate banks.

So call me simpleminded, but I just don’t get why so many people think depositors losing their money is a good idea and would solve moral hazard. Please explain it.

I agree.

Think through the implications of your proposal. Bank deposits would be guaranteed to infinity no matter how badly managed it is. There is no longer any need (or at least a very reduced need) for risk management on the part of the bank – the government provides an implicit hedge, cost-free to the bank.

Did the depositors receive interest on their money? Yes, and a good rate from what I’ve read. Don’t expect to get risk-free returns in life.

Think through the implications of your proposal. Bank deposits would be guaranteed to infinity no matter how badly managed it is. There is no longer any need (or at least a very reduced need) for risk management on the part of the bank – the government provides an implicit hedge, cost-free to the bank.

Did the depositors receive interest on their money? Yes, and a good rate from what I’ve read. Don’t expect to get risk-free returns in life.

I don’t know what interest rate they received, and frankly it is immaterial to my question.

If I applied this logic to everything else in the world, I shouldn’t get onto a plane without checking the plane’s maintenance records, what the pilot did in the last month, what food he ate, the entire supply chain of the fuel refueling the plane. Being able to fly to another country is a return versus walking, what risk should I accept? Similarly, I shouldn’t eat food without checking the farm it came from, surveilling the farmers, and so on. Not having to grow my food is a return, what risk should I expect? I could not trust the medicine I take. Basically I couldn’t do anything and would be paralyzed.

So what’s so special about banks that it is reasonable for them to be exempted from doing what it says on the tin? If anything, their entire job is risk management: keeping my money safe. So why is it up to me to do that for them?

The bank gets wiped out if it doesn’t do its job properly but I shouldn’t.

Well, banking is a unique industry and your comparable examples don’t compare because of the uniqueness of banking. (Highly leveraged, heavily regulated.)

Presumably you are either very wealthy or handling the accounts of a small-to-midsized firm if you have more than $250,000 in a single bank account.

In either case, you should have some knowledgeable advisors who would be looking for these types of red flags.

Cash management is still part of an undergraduate finance curriculum and it’s not exactly rocket science.

Uninsured depositors have been getting an implicit free ride and it’s not unreasonable for people to see the hypocrisy in a negative light.

No, the reality is commercial aviation is MUCH MORE regulated than banking.

You have to have approved regulated parts from inspected approved sources (fake parts are a real problem, FAA inspectors are sent around the world to inspect factories, materials, processes, record keeping), assembled in approved processes by trained licensed techs, inspected after every significant installation of parts, then testing by trained mechanics and calibrated equipment, test flights, more inspections, FAA inspections, customer inspections. And that’s just to get an airplane into service.

Then there are licensed, trained, medically checked out aviators, licensed, mechanics, licensed and trained people on the airplanes during the flight to keep you safe, inspections at airports, undercover agents on airplanes, mandated aircraft inspections and maintenance, mandated overhauls, FAA audits of everything with on site inspections.

Then there is a massive FAA air traffic control system, weather updates, ILS, facility standards and inspections.

Then there is a whole system dedicated to finding and fixing problems with aircraft that are actively in-service. A whole system of recalls, mandated re-work, emergency mandated re-work call Airworthiness Directives.

Here is the link to FAA Airworthiness Directives:

https://drs.faa.gov/

Here’s an example from an Emergency AD 2020-16-51:

There are HUNDREDS of ADs being worked at any given time.

It’s an extremely large extensive system that keeps aircraft and air travel safe, and it works well. But even then, one can argue that it is not good enough.

Why?

Because you cannot re-write the laws of gravity over the weekend.

And, yes, the fuel is inspected, tested, tracked, and kept safe with complete records from the refinery to into the airplane.

Record keeping in aviation, and military aviation has been joked about for years. For example, the C-5A Air Force heavy lifter, it cannot take off with all it’s records in the aircraft – too much paperwork.

So in other words, they are not comparable industries.

With some misgivings, I will try to address what I see as the differences.

The whole FAA system grew from the Air Commerce Act of 1926 as the aerospace industry grew, and the relationship between the regulatory agency and the industry is to advance the science and engineering that is fundamental to aerospace. There are definitely ties into the military, and the whole MIC because of aerospace’s obvious military uses. But the key takeaway from this is science and engineering. And the understanding that if you make a big enough mistake, you get a “forced off-airport landing” which is the AD way of saying CRASH.

And you have to understand, modern aerospace engineering is almost right at the limits. We have fasteners that are time and temperature sensitive, have to be temperature tracked from the moment of manufacturing (we keep them at -40 deg F) until installed where these air harden to full strength. We have test fasteners in test material from the same material batch that are destructively inspected and tested EVERY TIME, dimensions are checked to thousands of an inch, sometimes smaller, hardness is checked, microscopic inspections for cracks. Composite materials keep at cold temperatures where there is a time limit to letting them warm up to where these can be worked, and then a time limit to set them in molds, and cure in an autoclave. It is an industry that has learned the hard way that what seems like a small mistake can end up causing much bigger problems.

To be honest, I think a comparison of the science of “economics” and the science as used by the aerospace industry is largely a joke, and as much as you put fancy math formulas to economics, it remains much more tied to human behavior, how societies work, and human and societal values. I like the name “political economics” better because much of “economic science” seems to be a political belief presented as science. I tend to think MMT, which is somewhat devoid of politics as the better modeling tool of economics because it seems more aligned with reality, but I also think double entry bookkeeping, and computing interest are well known and regulated until you introduce things like ratings agencies, and mark to market.

And that’s how you can get one Treasury Secretary that says X, and after an election, with a new Treasury Secretary, they say Y. Because it’s not a hard science, it’s politics.

That’s not to say either system is above failure, crime, or corruption. These are both systems run by humans who can drag problems into all systems. Right now, I think airlines, aerospace manufacturing, and the FAA are struggling. Many experienced workers have retired, many companies have under invested in both facilities, equipment and personnel, and agencies are understaffed and overworked. But who really is in favor of lots of airplanes falling out of the air?

To be naive, I wonder why we don’t go back to the banking regulatory framework from the Great Depression such as Glass-Steagall and such. That seemed to work well, and when science is lacking, just go with what has a track record of being simple and having worked.

The tin (to preserve your analogy) has a warning on the back in bright red letters. This warning was well-known to the public–those FDIC stickers have been in every bank I’ve ever seen.

Nonetheless, in broad terms, your argument is fair for individuals–but most individuals do not have $250,000 in any bank.

Does it work for businesses? I’m not so sure.

Business in general is all about risk management. The individual citizen cannot reasonably be expected to track the origins of his or her food, yet a restaurant can and should be familiar with and confident in its suppliers. Likewise, a hospital better be certain that it is not ordering defective medications. In fact, the restaurant and the hospital may be legally liable for relying on defective supplies, even though they had nothing but the best intentions.

A relatively remote business risk is bank failure. It is possible to work around this by spreading money among several institutions, using money market funds, etc. Alternatively, if it is necessary to hold significant amounts of cash in one bank (e.g., for some reason Roku had most of $500 million at SVB), private insurance could be purchased as excess coverage over the FDIC amount.

The ad hoc system introduced now is essentially 100% deposit insurance, but with the possibility that this new excess (above FDIC) coverage will add to the costs of all banking customers because the premium for this “insurance” is essentially taking the form of a “tax” on all Federal Reserve member banks. The cost instead should be allocated to those who hold large bank balances because they are the first beneficiaries. Those parties that would hold large bank balances also have other risk management strategies available if paying this premium is unacceptable–for example, putting excess cash in money market accounts or T-bills (really the same thing, just in different forms).

If you’re managing a large account much over the FDIC insurance limit in a bank and wonder about the bank’s soundness you can find financials for banks online. Many years ago there were 2 or 3 publicly available sites for bank ratings, financials, and last FDIC report. The simplified data was free. The ranking was in star ratings, 1-5 stars with 5 being the highest. Now there’s still one online site offering this data, but now it’s not free. You can buy the Highlights and summary reports for less than $75 combines. The more detailed reports cost more. Worth the price, imo, if you’re keeping funds over the FDIC limit in a bank.

Here’s the last entry for Silvergate:

https://www.bauerfinancial.com/star-ratings/tell-me-more/?cert=27330&type=B&urllink=www.silvergate.com&instname=Silvergate+Bank+-+La+Jolla%2C+CA

The current entry for SVB bank reads FDIC RESOLVED (no stars)

Thanks for the website! I’m not over the limit, but that’s a useful resource.

Call report data is available for free: https://cdr.ffiec.gov/public/ManageFacsimiles.aspx

I think a better response is to provide the backdrop of banking in the United States prior to the formation of key banking entities following the Great Depression. There had been a history of bank runs and ruinous periods of recession dating to the time of Andrew Jackson. And even after the changes following the Depression, there were periods still when things run amok; of course there was the S&L Crisis of the middle to late 1980s. Bankers in Texas I used to work for, had a really long memory about that episode. I’ll carry memories from 2006-2009 for as long as I live.

I’m not going to read this out loud or provide any cliff notes of the sort. Feel welcome to dig through this literature at your own personal leisure. Needless to suggest that lessons learned following the Great Depression made an impressionable, indelible mark.

https://www.fdic.gov/bank/historical/brief/index.html

https://www.fdic.gov/resources/deposit-insurance/understanding-deposit-insurance/

Such an open ended question about deposit insurance is akin to asking a similar question of why historically (until the late 1990s, thanks Bob Rubin and Larry Summers) that commercial banks and investment firms were necessary to be kept apart aka Glass Steagall. My advice is to kindly arm one’s self with the working knowledge of why financial institutions need be both financially solvent, and capital sensitive while averting or controlling for obvious risks (and yes, with an eye to positive return on investment; negative returns just lead to ruin).

I agree. A brief history of the Glass-Steagall Act.

https://www.history.com/topics/great-depression/glass-steagall-act

I’ll note in passing the FDIC insurance limit on deposits was raised in 2010 to the $25o,ooo it is today. Raising the limit, considering the current inflation, might be a good idea. Eliminating the upper limit on insured deposits would be a disaster, imo.

I agree, but the big depositors have been getting a freebie. The Fed has now set a precedent: wealthy account holders now have free deposit insurance over $250K. According to this professor at Vanderbilt, either enforce the $250K cap or end the subsidy. Key quote:

Apparently, the $250K cap was put in place because wealthy depositers were expected to use their influence to help keep their banks’ practices safe. Since they are obviously not doing that, the cap serves no purpose. Will Congress remove this cap? If it doesn’t, it’s a smoking gun that Congress sides with money and not the public interest.

Sure, the argument makes sense in a vacuum.

However, your proposal was NOT the legal rules on March 9, 2023, and these rules were not obscure or even difficult to understand. SVB paid for FDIC insurance to the amount of $250,000 per depositor. The bank did not pay for insurance to a higher amount, and SVB customers did not bear any incidental charge for more insurance. Presumably, SVB allocated the cost of FDIC insurance (already underpriced, from my understanding) among its customers, whether depositors (reduced interest payments or greater fees) or borrowers (higher loan charges).

The rules are now changed because of “systemic risk.” But, realistically, the rules are changed to benefit connected depositors. These depositors probably would have gotten most of their deposits back once FDIC finished liquidation. instead, due to government fiat, these depositors are now made whole immediately, with the possibility (probability, in my opinion) that the bank customers throughout the ENTIRE COUNTRY will pay more to subsidize this new “program” that benefits only those depositors with more than $250,000 in a particular bank.

The bottom line is SVB depositors are, as I said in a previous post here, getting a commercial benefit for which they did not pay–the certainty of being made whole. They, and all similarly situated bank depositors (>$250,000 accounts), should be directly charged market rate premiums for this new backstop so that the costs are not passed on to the regular individual banking customer.

Moreover, your argument favors a postal bank instead. There’s no social benefit in having private banks encouraged to take extra risks due to this 100% backstop/bail out approach, and any governmental regulation will likely be defeated or reduced over time. A postal bank paying 0% interest or near 0% interest (the lack of interest payments being the “fee” for safety), plus private banks with no insurance other than what they purchase on private markets, creates a system where a trusted bank is available and commercial banks have incentives to behave wisely.

Seconded. The problem with shouting ‘moral hazard’ at the occupants of sinking boats rather than throwing them a life-line is that many of those occupants are employees who now aren’t going to get paid and may lose their jobs, or suppliers of goods or services to businesses who’ll have to eat the cost of them, none of whom had any say in where their employer/customer/client banked.

Having a judge and jury to decide the culpability of every individual and business affected, and choose who deserves saving and who should drown would be nice but is impracticable. The alternatives are to save everyone or let everyone drown. Neither is fair but that’s life.

As long as the SVB depositors now pay for the benefit they are receiving, I’m fine with it. But that’s not the case–in the end, the plan is to let the SVB depositors receive the commercial benefit of insurance coverage without the payment (direct or indirect) of premium. (Remember: Banks and credit unions pay actual premiums for the $250,000 deposit insurance.)

“The alternatives are to save everyone or let everyone drown.”

I’m going to pour me some wine and try to think of all “save everyone” policies the USA has ever done.

Thank you to everyone who answered.

My first impression is that this ad-hoc change is in some sense an improvement since now every dollar is insured, and presumably equally “taxed” for this insurance, whereas previously only some dollars were. It’s not obvious to me that this should lead to higher costs for small bank holders — did the banks really subsidize the FDIC payments of smaller account holders by spreading the insurance cost over account holders rather than dollars even though each account holder was only covered up to $250K? Secondly, although, theoretically, some of these dollars belong to rich people who could weather the loss, a significant amount will belong to businesses who would weather that loss by sacking people, thereby hurting those who cannot weather the loss. Therefore guaranteeing each dollar should also be in the interests of those with small accounts, who rely on said jobs.

However I’ll have to read through all the material you’ve linked to in detail to see whether or not this impression is correct.

(With regard to a Postal Bank, I see what you are saying Fraibert. That would be a big change from the current status quo. It’s an interesting question.)

Thanks again!

Just to be clear, the FDIC assesses banks an actual insurance premium for their deposits (same with credit unions for their credit union equivalent). The banks can cover that premium cost however they want (it’s a cost of doing business–so it gets covered somehow), but the bottom line is a bank like SVP did pay for the $250,000 level of depositor coverage (with some additional rules for different types of accounts).

Generally speaking, this $250,000 level of coverage sets the bare minimum each depositor would retain after a bank failure. The depositor with an account larger than the $250,000 level may (always has, I believe) get more than that insured amount as the FDIC liquidates bank assets and distributes that money to depositors.

Since banks were not assessed premiums for 100% guaranteed deposit coverage, I can’t fairly say that depositors have any commercial or legal entitlement to that amount of coverage. Any grant of additional coverage without payment of the obvious cost of that coverage is a subsidy. You can argue that it’s a fair or even necessary subsidy, but it’s not one for which SVP depositors have any entitlement to under the law and I think those who will directly benefit should pay for it.

As it stands, given this new system where the Federal Reserve assesses member banks to cover deposits above $250,000 at a failed bank, it seems likely that the banking industry as a whole will attempt to pass that cost onto customers. That’s how business works, after all.

As an analogy, imagine that you own a barn that has a replacement cost of $80,000 in 2005 and you’ve paid premium for that $80,000 since 2005. Unfortunately, the barn burnt down yesterday, and the contractors tell you that the replacement cost is now $100,000 due to the large amounts of recent inflation.

Since you’ve only paid for $80,000 of insurance, there’s no reason the insurance company has to give you $100,000 because that amount of coverage was not part of the contract. Demanding a retroactive change to the policy is not reasonable because you simply did not pay for the additional $20,000 in coverage.

Basically the same here, except the bank paid for the insurance on behalf of the insureds.

Naked Capitalism University

Kind of amplified in this case as 80/100 understates the risks borne.

Because, basically, it keeps those with little money (the depositors) in their place (and in their role) as the source of the raping and looting by those with the big money. It’s a social issue, not a financial one.

Up to $250,000 cash in a single bank account is not “little money”.

And you seem to have missed that a blanket deposit guarantee is a license for banks to go hog wild with risk-taking.

Never realized where the money for the B Word might actually come from, despite…

This is the first I time realized the following. Have there been any NC articles about the perniciousness of bank fees?. The cite is from the ever prescient and often seemingly omniscient [just like NC!] Tablet Magazine Link below.

“Have there been any NC articles about the perniciousness of bank fees?.’

Yes and in connection too McKinsey & Company fee structuring including revolving debt and lowering credit standards to trap consumers in it …

Best article I have yet read on SVB collapse.

Wonderful tidbits like: “any judgment on the risk of contagion may be premature.”

As well as: “The rational for permitting HTM securities to be held at amortised costs rather than current value is unclear.”

“The puzzling thing is why SVB did not pursue several avenues available to manage its evolving risks.

Given that the credit quality of its securities was high and they would pay back in full if held to maturity, it would have been open to SVB to used them as collateral to borrow funds, through the repo market or from the central bank, to meet deposit withdrawals. Lender-of-last resort facilities provided by central banks are specifically available to meet these contingencies.” -S Dat

______________________________________________________

This should be the question that everyone is asking.

The explanation of how banks came to have all this surplus bonds is that the Fed had stuffed the banks full of money with QE.

The growing difference between US bank loans and deposits starting in 2009 was the result of QE where the Feds purchases of govt backed securities created deposits in the banking system (the new deposit holders got deposits in exchange for giving up their securities). The banks were forced to assept these deposits in exchange for credits at the Fed which they could use to purchase govt securities if they wanted to earn more than the meagre interest on Fed reserves. In other words, QE ends up on the US bank balance sheets as either a cash asset (Fed deposit) or as govt securities. The liquidity problem for a bank arises if the bank chose to use cash to buy long term securities.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/fredgraph.png?g=11bSc

Thanks for posting Das. He’s so heavy but just about the time your brain begins to boil over he cracks a few jokes and I spit my coffee – even though I don’t completely get it. Das is wonderful. So I am left puzzling about the unfinished idea of mortgage, based on time but with no counterbalance, like some anti-mortgage on the books that automatically prevents any sort of default from contaminating the entire system. If finance is kept in balance it would prevent “relative equity” from “reducing market confidence in the currency or sovereign credit.” Silicon Valley should develop an app for that at warp speed. So… that’s why it’s good to bail those guys out.

here is where it made me burn, not even sanders or the squad understand this, their actions in congress betray their real understanding of what happened,

“Normally, this liquidity would be deployed as loans. However, since the 2008/2009 Great Recession, loan demand has been relatively weak and well below deposit growth. Between Q4 2019 and the first quarter of 2022, only 10-15% of deposits growth at US banks was lent out. Banks had to seek out alternative investments.”

what that says is that obama bailed out bill clintons disastrous polices to the tune of at least 29 trillion dollars(kelton pointed this out), and hammered the worker at the same time.

surprise surprise business never came back. as hudson has said, “we are still in the obama depression”

bailouts, lets go back to bill clintons disastrous terms, nafta, then bailout, free trade with asia, then bailout, russias enters the global economy, then bailout, the biggie happened just as bill clinton left office, his banking, commodities, derivatives, free trade with china, his repeal of glass-steagle, then a massive implosion. if bush had not dropped helicopter money after 911, we were on our way to a very serious recession or depression.

as both hudson and powell has said, its the imports that is helping cause the inflation.

coupled with all of the bailouts since 1993 then should we be surprised by the roaring inflation?

this should be true for the politicians that created this mess,

“Amusingly, Silicon Valley’s famed libertarians who resist any form of government regulation are pleading for action to prevent an “extinction event”. Some 3,500 CEOs and founders representing some 220,000 workers signed a petition started by Y Combinator appealing directly to the US Treasury Secretary to backstop depositors, warning that more than 100,000 jobs could be at risk.

The moral hazards around bailouts are well known. It seems now that tech start-ups like banks, auto businesses and anybody with an effective lobbyists are too big to fail even if they are too difficult to understand or to properly manage. As Herbert Spencer put it: “The ultimate result of shielding men from the effects of folly, is to fill the world with fools.”

Over the last decade and a half, the economic system and financial practices have become geared around low rates, abundant liquidity and the authorities underwriting risk taking. Moving away from this state of affairs was never going to easy, that is, if it is possible at all.”

the real idiots that made this mess, are not the libertarians, if you say to your immature child, sure, go into the candy store, eat as much as you like, but regulate yourselves so that you do not get sick.

well they got sick, idiot politicians like obama said, they learned their lesson, and we will bail them out, and not reverse bill clintons idiotic polices who said they learned their lesson, well low and behold, the libertarian very immature children did not learn a lesson, nor can they ever learn a lesson.

and all at the same time the clinton democrats blame labor for everything.

so we should hold them “ALL” responsible for their follies.

Thanks for the article.

It suggests that some pretty astute lobbying was performed by the tech bros.

Was Nancy P. a customer I wonder?

Apparently the bank is “closed pending sale.” According to Business Insider (as of 10 hours ago) a buyer for SVB is still being sought. According to this report, even the SVB bondholders will be wiped out. But will they, really?

Interestingly the parent of SVB, “SVB Financial” is not in receivership and has other entities with assets that could be used to help cover SVB’s losses. What’s odd is that “SBV Financial” bonds are still trading above zero. Someone out there thinks this will be resolved in a way that will keep some residual value for the parent. So, even though SVB seems “owned” by the FDIC now, certain Fed actions, like accepting SVB’s securities as collateral for cash “at par” rather than market value may leave SVB or the parent with some potentially significant residual value. Certainly, if the Feds do find someone to buy SVB–and if the Feds continue to give very generous treatment of SVB–both bondholders and stockholders may not be wiped out after all. That would be pretty bad optics, so my guess it won’t end that way, but we’ll see. Personally, I want to see blood on the floor: clawback of recent management insider trades and bonuses, and big haircuts all around. Pass the popcorn.

This all seems to be begging the question, “Why isn’t banking public utility?” It’s my understanding that all depositers will be made whole, and the losers are the banks equity and debt holders. So, who needs equity holders, debt holders and an incompetent BoD in charge of a lending institution? Nationalize the entire shebang, and allow the pols to steal the money instead of these entitled $hitheels.

It seems to me that there’s two main components of traditional banking. One is the component is that of money storage and payments. This element could be made comfortably into a public enterprise (i.e., a postal bank). The postal bank could readily do things such as take deposits, issue debit cards, process checks, etc. With that said, privacy would be a major concern.

The other component of traditional banking is loan making. I am not certain that government is competent in this area, where business sense is important for success.

As I’ve written comments on this whole banking crisis, I’ve therefore come to wonder if a hybrid system is best. A postal bank should be established as a safe store of cash (though without paying significant interest on deposits), with deposits at the bank fully insured or at least insured to a high level (several million USD). Private banks can still take deposits but any deposits offered at these banks would be subject only to insurance coverage that the bank acquires for its depositors or which an individual depositor purchases on the private market. (If desired, the FDIC could insure the private banks while charging market rate premiums.)

This gives citizens a super-safe low cost (but low interest) option, as well as a way to make some more interest at a private bank. Private banks have the incentive to compete on interest offers, but their behavior would be limited by the insurer’s monitoring. Moreover, private banks would still want to secure deposits as an additional source of capital to make loans, as well as creating business relationships with potential borrowers.

Uh… Central Bank owned and controlled entirely. Central Bank Digital Currency? What could go wrong? No.

The banking world is diverse: nationally chartered banks, state chartered banks, state chartered savings and loan companies (banks), and credit unions (banks).

Better regulation, tighter regulation is the answer, even if it looks like an impossibility at the moment. ( I wish someone had appointed Bill Black and his team to examine what went wrong in 2007-8 with the banks that led to the Great Financial Crisis. I don’t think the pols really wanted to know. Whitewash was the order of the day, imo.)

Arguably the cornerstone of any society is The Law. These are the values we wish to live by and we elect individuals who we hope wish to apply those values by creating laws which perform that duty. It’s not perfect, but other systems are likely inferior.

Under the Laws (esp. bankruptcy,) depositors are not “depositors” per se. Strictly speaking they are creditors. (Hence the term, “account is in credit,” meaning the bank owes you your deposit back should you demand payment of it. The bank will only have to fulfill this contractual obligation if it has the means to do so. At a point close to bankruptcy it likely will not be able to do so. It will cease trading and all remaining depositors who have not withdrawn their cash will be locked out and will have to stand in line. As a creditor.)

That’s what legally should happen and in the past is exactly what happened. It happened in 1929. There were no bailouts. The law was applied exactly how it was intended. And many folks were simply wiped out.

Society’s economic environment was market based. Meaning you chose to get involved, if you wanted to. If you felt you didn’t have much choice, then it was up to you to work around that problem.

The prevailing legal principle, caveat emptor, (“let the buyer beware”) puts the responsibility onto the buyer, in this case the depositor, to take responsibility for their actions! That’s ALL their actions, irrespective of whether they deposit $1 or $1million.

This is why depositors should not be made whole, it’s the cold hard law! It is unfair that some bank depositor’s losses should be made whole when they knew OR should have known the risks. The principle of caveat emptor applies similarly to, say, people who are involved in a car crash and the vehicle is destroyed. Should they be able to get a new car, paid for by government, their reason being simply insisting that such a thing is fair to do? If so at what point do we stop bailing out everyones personal disasters?

Not bailing out depositors arguably improves things for everyone else who have not lost anything. Otherwise we enter a world where every, loser, addict, costs of sickness, homeless person, car crash victim and on and on, etc etc becomes your responsibility to pay for.

If a depositor is a creditor and if Caveat Emptor puts the “responsibility onto the buyer”, is not the bank the “buyer” and therefore “should have known the risks”?

Warren calls for Powell to recuse himself from the SVB investigation he launched.

This sounds right. After all, the Fed’s actions (and/or inactions) may well have contributed to this crisis. For this and other reasons, I question why the Fed is leading this investigation at all.

The FDIC, which has the requisite expertise and investigatory power (e.g. subpoena power), and which is now operating the “FDIC Bank of Santa Barbara” (as SVB is now called), could perhaps do its own investigation without the kinds of conflicts of interest that Warren is rightly concerned about.

Who has the power to do “discovery” of the Fed’s own internal communications in the lead-up to this crisis (or am I naive to even ask this question)?

I doubt the FDIC can probe the Federal Reserve, though that’s a guess without detailed research. However, without question, Congress (either House or Senate, or both) can, as part of its oversight powers.

However, I expect that the Democrats will resist too much inquiry given the political connections involved here.

Some seem to forget neoliberalism was an agenda to establish a two tier market society with rights and wealth for the very top and good luck too the rest ….

Everything else is just narrative creation ….