Yves here. The Department of Defense started warning in the early 2000s that global warming would generate destabilizing mass migrations. But Americans like to this this sort of thing happens in poor countries near the equator, or coastal Florida. But a new book by Jake Bittle argues that the Great Displacement is coming here too.

By Jeff Masters, a hurricane scientist with the NOAA Hurricane Hunters from 1986-1990 who co-founded the Weather Underground in 1995. He served as its chief meteorologist and on its Board of Directors until it was sold to the Weather Company in 2012. Originally published at Yale Climate Connections

A massive worldwide societal upheaval is underway — the uprooting and displacement of huge numbers of people living in places growing increasingly risky to live in because of climate change. “The Great Displacement: Climate Change and the Next American Migration,” by Jake Bittle, a staff writer for Grist, is a must-read account of this hugely important transformation. The title is a reference to the Great Migration of the 1920s through 1960s — the largest single migration event in American history — when more than 6 million Black people left the South and moved to northern cities.

Focusing on the United States, Bittle traces the stories of a new generation of domestic climate migrants, displaced in an unpredictable, chaotic, and life-changing way: “These people live in every corner of the country, from the waterlogged streets of Miami to the parched cotton fields of Arizona. They run the gamut from minimum-wage workers to millionaires, from liberals in big coastal cities to entrenched small-town conservatives. Their stories range from the tragic to the comic and from the inspiring to the infuriating. Indeed, there is only one thing they all have in common: they are moving.”

What makes this book particularly effective are Bittle’s interviews with people, which brings the human impact of climate change to life and provides a vivid picture of the challenges faced by those who are forced to leave their homes behind. Included are stories of Americans displaced by fires in California, drought in Arizona, sea level rise (in Norfolk, Virginia, and southern Louisiana), and from hurricanes (Hurricane Harvey in Houston, Hurricane Irma in the Florida Keys, and Hurricanes Fran and Floyd in North Carolina). Too often, it is the poor and marginalized who are most affected, with the rich and the privileged receiving the greatest help from the disaster relief system. Bittle advocates for the government to put in place policies to address the lack of affordable housing, ensuring that everyone has access to housing, before and after disasters.

Are People Leaving California Because of Climate Change?

The book opens with the story of Greenville, California (population 1,000), which was 75% destroyed by the Dixie Fire of 2021. Bittle documents how the displaced residents of Greenville suffered from an underfunded disaster relief system, a dire shortage of affordable housing, and a broken insurance market. “These same factors are fueling displacement in other parts of the country, after other kinds of disaster: climate change is applying stress to an already brittle social and economic order, widening cracks that have been there the whole time.” According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county that Greenville is in, Lassen, had the largest decline in population of any U.S. county for 2021-2022 (6%).

In a later chapter, Bittle follows people from Santa Rosa, California, who were displaced by the 2017 Tubbs Fire. Five years after the fire, a lack of nearby affordable housing and an insurance crisis have left portions of the city looking like they are just beginning to recover. An insurance gap — caused by homes that cost in the millions, but fire insurance that can only be purchased to cover a few hundred thousand dollars in damage — was so extreme that “many residents chose to cut their losses and buy somewhere else rather than spend countless thousands of dollars to rebuild homes in an area they knew was dangerous. They sold their empty lots to investors and speculators from out of state, most of whom sat on their holdings and waited for the price of land to rise rather than build new houses.”

Despite Climate Change, People Are Still Moving to High-Risk Places

Migration patterns in the U.S. over the past decade would seem to contradict the idea of a climate change-induced Great Displacement. People have been leaving cooler Rust Belt states like Ohio, Illinois, and Michigan, flocking to places with increasing climate-change-induced risk: the ocean coasts and the hot, dry West. Almost 100 million people in the U.S. now live in coastal counties. And the fastest-growing state in 2022 was Florida, which is at high risk from sea level rise, extreme heat, and hurricanes. Five of the 15 fastest-growing cities from 2020 to 2021 were in Arizona, which faces an increasing risk of extreme heat and water availability.

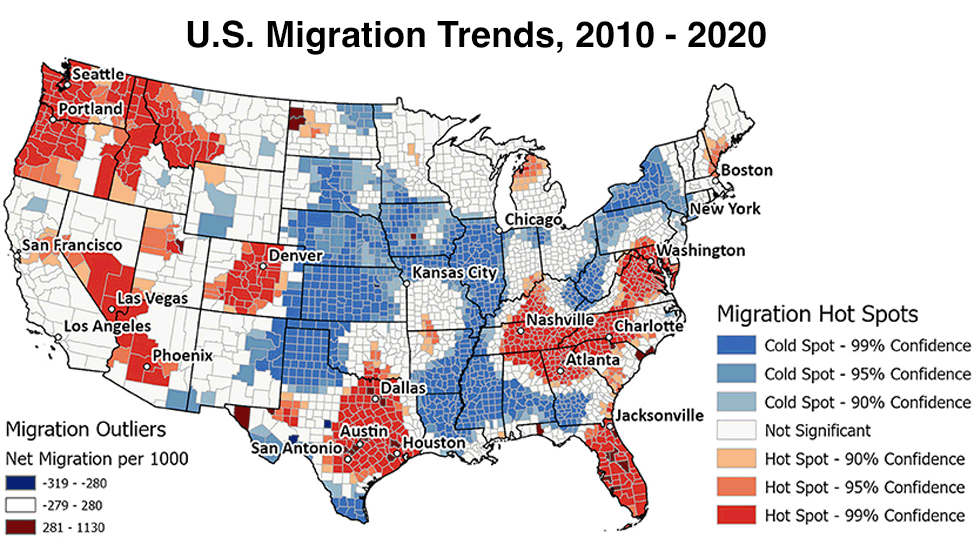

A 2022 study, Flocking to fire: How climate and natural hazards shape human migration across the United States, found that from 2010-2020, people moved away from areas prone to heat waves. But they moved toward areas at risk of river flooding, earthquakes, hurricanes, and wildfires. Not surprisingly, people also move for social and economic reasons — in addition to environmental reasons like the weather — and the study found that after controlling for all of these factors, people moved away from areas most affected by heat waves and hurricanes but toward areas most affected by wildfires; people also moved toward areas with warmer summer and winter temperatures, including metro areas with particularly hot summers. “These trends suggest that migration is increasing the number of people in harm’s way, even as climate change continues to exacerbate summer heat and contribute to more frequent and severe wildfires,” the researchers wrote.

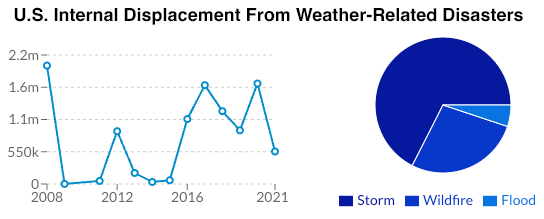

Two major exceptions to this trend of movement toward risky areas over the past few years include California, which has lost population thanks to exorbitant housing costs and a wildfire crisis, and Louisiana, which has been pummeled by multiple hurricanes and is also suffering an insurance crisis (according to the U.S. Census Bureau, four of 10 of the counties suffering the largest percentage decline in population during 2021-2022 were in Louisiana). According to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Center, wildfires in California (population 39 million) displaced 597,000 people in 2020 and 159,000 people in 2021; in Louisiana (population 4.6 million), Hurricane Laura displaced 585,000 people in 2020, and Hurricane Ida displaced 257,000 people in 2021.

NEW: Growth in the nation’s largest counties rebounds in 2022 with migration and growth patterns edging closer to pre-pandemic levels.

All 10 of the top fastest-growing counties were in the South or West.

Explore more highlights: https://t.co/cFVjORJj19 pic.twitter.com/FbR8UfsySH

— U.S. Census Bureau (@uscensusbureau) March 30, 2023

Bittle argues, though, that the patterns of displacement that arise because of climate change have already begun in small towns and remote places. Over time, the instability will spread to major cities and entire regions: “As disasters continue to pummel our housing markets, public and private powers will push more people out of vulnerable areas, and escalating fear of danger will spur more to move of their own volition. The result will be a shambling retreat from mountain ranges and flood-prone riverbeds, back from the oceans, and out of the desert. It will take decades for these movements to coalesce, but once they do, they will reshape the demographic geography of the United States.”

He cites a survey of more than 2,000 people in the U.S. conducted by the real estate company Redfin, which found that almost half of those planning to move in the next year were motivated by natural disasters, more than a third were motivated by rising sea levels, and three-quarters of the respondents said they would hesitate to buy a home in an area threatened by climate change, even if it were more affordable. Another study, from Cornell University, found that 57% of the 1,000 respondents in a nationwide sample said that climate change would have at least a “moderate” effect on their decision about whether to move over the next decade. Sea level rise is already lowering coastal property value, according to a 2019 study: “Homes exposed to sea level rise sell for approximately 7% less than observably equivalent unexposed properties equidistant from the beach.”

By a ratio of 59,000:5,000, North Carolina construction of new homes in 1-in-100-year flood plains far outpaced the number of buyouts 1996-2017, according to new research. It’s like the behavior of a smoker told to quit who keeps smoking.

Read more at: https://t.co/QQHc9fiEO7 https://t.co/2V2f02xEJ9

— Jeff Masters (@DrJeffMasters) February 8, 2023

I’ll give you a guess how this is going to end https://t.co/Pm2pkD13lv

— Eric Fisher (@ericfisher) January 25, 2023

Buyouts Can Help People Leave Flood-Prone Areas, but They May Not Be Enough

The book does a great job explaining why so many people live in flood plains and near the coast in regions subject to flooding — ignorance about how floods work, plus an economic dynamic that sociologists call the growth machine: “More construction meant more money for developers, more people living in waterfront towns and cities, and more tax revenue for local governments. A booming tax base allowed more spending on public services, which in turn attracted more people, created more demand for construction, and spread more money around.” This process was encouraged by FEMA and the Army Corps, which endeavored to keep flood-prone communities where they were: “The Corps wrapped levees and sea walls around existing towns to protect them from flooding, and FEMA stepped in after flood disasters to help people rebuild.”

Read: ‘Is it foolish to hold onto my family’s beloved waterfront home?’

Beginning in the 1960s, with growing realization that this model was unsustainable, the National Flood Insurance Program was created. People who wanted to buy a home in a flood plain were required to get flood insurance in order to receive a federally backed mortgage. This approach was supposed to discourage people from moving into flood zones, but the price of the insurance was set too low, resulting in the government subsidizing people living in high-risk areas. It wasn’t until 1989 that FEMA was finally allowed to stop exclusively rebuilding in the same place after a disaster, but instead prevent future flood losses by buying out homes that suffered repeated flooding.

But buyouts currently comprise less than 20% of FEMA’s flood risk reduction budget, and this initiative has been seriously flawed. “The Great Displacement” describes the yearslong, convoluted process experience of residents of Kinston, North Carolina, after flooding from two hurricanes (Fran in 1996 and Floyd in 1999). Among the many issues: FEMA disproportionately funds buyouts of vulnerable properties in White communities compared to communities of color, because money is allocated based on a cost-benefit analysis that prioritizes more expensive properties. In addition, wealthier communities may also have more resources to influence decision-makers who decide who gets a buy-out. It’s clear from Kinston’s experience that FEMA must drastically improve the buyout process to avoid massive chaos in the coming decades when sea level rise and heavier precipitation events will likely force millions of people to abandon risky flood-prone areas. Between 1989 and 2017, just 40,000 buyouts occurred.

The book reviews a few alternatives. The government could buy flood-prone homes, then rent them back to their owners until a flood comes, at which point the owners could leave. In Surfside, Florida, developers and the city contribute equally to a “relocation fund” intended to offer grants to assist people moving from flood-prone areas. Government-brokered land swaps could be arranged between homeowners in flood plains and landowners outside of flood plains who have extra land they want to develop. The Norfolk area nonprofit Wetlands Watch has proposed that the city only allow developers to build on high ground if they first purchase a few homes in flood-threatened areas, allowing those homeowners to make a clean escape. When the occupants move out, the city would clear the land.

With Sea Level Rise, Every Coastal Home Is Now a Stick of Dynamite

Long before rising seas inundate coastal cities, the coastal real estate market will fall, and once property values decline, they will not go back up, Bittle writes. He likens owning a coastal home to holding a stick of dynamite with a long fuse.

“When humans began to warm the Earth, we lit the fuse. Ever since then, a series of people have tossed the dynamite among them, each owner holding the stick for a while before passing the risk on to the next. Each of these owners knows that at some point, the dynamite is going to explode, but they can also see that there’s a lot of fuse left. As the fuse keeps burning, each new owner has a harder time finding someone to take the stick off their hands.

“What should we do with the dynamite? For how long should people be allowed to keep passing it around? Who should be responsible for throwing it away? And how can we move everyone out of the blast radius? As of right now there are no answers to these questions, and indeed there are very few people willing to even ask them. For the moment, the coastal housing market is a three-way staring contest, with homeowners, governments, and real estate industry figures all straining to keep their eyes open, to keep up the pretense that everything will be fine.

Sooner or later, though, someone is going to blink.”

The Future of Climate Migration in the U.S.

Bittle argues that “managed retreat” is unlikely to happen on the mass scale needed in coming years because sea level rise will simultaneously affect huge portions of coastal real estate worth many billions. “But just because there won’t be a managed retreat doesn’t mean that there won’t be a retreat,” he says. The combined value of all the coastal real estate in the United States that faces flood risk from sea level rise is somewhere between half a trillion and 2 trillion dollars — about 2-4% of the national economy. Sea level rise will “cause a plunge in coastal property values that will inflict economic harm even on people whose homes have not suffered any damage, sharply reducing the value of the most valuable assets they own. As a city’s housing values decline, so, too, does its tax base, which means less money to pay for basic services like trash collection and street repair. Among the portion of the population that stays, there will be many who want to leave but can’t, who are tethered by their mortgages to homes they can’t sell.”

Where will the displaced people go? Bittle cites the work of Mathew Hauer of Florida State University, whose research found that the younger and wealthier members of a given community will tend to leave first and that these people will tend to move to the nearest large city that does not face extreme climate risk. In the long run, Bittle foresees that cities in the Midwest will see runaway growth of the same kind that places like Austin and Phoenix are seeing now:

“It is almost a certainty that by the end of the century there will be a substantial flow of people toward relative safe havens and away from the riskiest and least hospitable places. It may take decades for these demographic flows to coalesce, but barring a profound shift in climate trends or government policy, many people will move northward. The driving force behind their migration will be the same force that has stacked up houses on eroding coastlines and bent the water system in Arizona out of shape to accommodate new development. Our profit-driven society relies on economic growth, and the climate crisis will make some areas far more conducive to growth than others.”

It’s Not Too Late to Prevent the Worst

“The Great Displacement” is a timely and important book on the climate change-induced mass migration that has already begun and that will fundamentally rock society. It is a powerful reminder that we have a responsibility to act now to prevent the worst effects of this crisis. Bittle’s final recommendations include a call to reduce climate-warming pollution, ramp up investment in post-disaster aid and climate adaptation measures, reform the National Flood Insurance Program and the private fire insurance industry, allow increased numbers of international climate migrants to enter the U.S., and address the lack of affordable housing by ensuring that everyone has access to housing — before and after disasters.

For those wanting to learn more about this critical topic, another great book is “Nomad Century,” by Gaia Vince, which argues that migration should be encouraged because it drives economic growth and reduces poverty. The author calls for a safe, fair process for migration, overseen by a global agency with powers to police it. Another recent book, which I did not get a chance to review, is “Planetary Specters.” It argues that to understand the systemic reasons for displacement, it is necessary to reframe climate disaster as interlinked with the history of capitalism and the global politics of race.

“The Great Displacement: Climate Change and the Next American Migration” (Simon and Schuster, 2023) is $14.99 on Kindle at Amazon.com and $28.99 in hardcover.

I can see two different forces that will be factors in how the population sorts itself out. First you will have the real estate industry which will, through low land prices, encourage people to move to certain regions. They will not reveal that the reason that the land is so low-priced is that it is vulnerable to climate change. So the post notes that Arizona is one of the fastest growing areas, in spite of the fact that over time the region may become a barren zone through lack of water. And then you have Florida where the problem is that this region will have too much water – sea water. The only industry in Southern Florida in a century from now will likely be scuba diving tours of Miami.

The second factor is the insurance industry which naturally will not want to continuously pay out for areas that experience floods, fires, etc like clockwork. I would guess that they would be quite happy to nominate some areas like coastal strips as non-insurable. You may have push-back from wealthier people to force the insurance companies to keep on paying for their mansions as they get destroyed from time to time but gradually the costs will be too prohibitive. In passing, I note that these two forces – Insurance and Real Estate – are two of the three legs of the FIRE sector of the economy. And the third leg of this triad – the Financial sector? They will come down on the side of where the money is – or where it is not hemorrhaging away.

Very astute, RK, particularly for someone living at the Other End of the Planet. I find most intriguing the question of insurance. When I retired and moved home to Western Mass. from Southern California, my fire insurance bill dropped to less than a fifth of what it had been before. That was more than 20 years ago. And the SoCal tab was for a plan run by the state (I think it was called the California FAIR Plan). I wonder what the difference is now.

Kev, I have a friend’s family moving to Perth. How do you see Australia’s response to this concept, migration internally? I haven’t seen an encouraging response from your government regarding the fires and floods of your region to date. Seen any interesting articles regarding positive discussions re. climate disasters in your continent? Peace.

The previous government was a disaster as regards climate change (climate change deniers) and the new one, well, remains to be seen. ‘Fraid I haven’t much info as I have not been following this story here much. However your friend and his family should find Perth to be a good place to move to and will find life different to what they are used to elsewhere.

A good number of home & cabin owners insurance policies are not being renewed here in tiny town & Mineral King, and I get it, we’re tantamount to Section 86, with a couple of fire priors.

If you rebuild it, the insurance company won’t come.

That said, I like my chances here in a place the Wukchumni were for thousands of years, and that includes a 243 year & 135 year long drought in the midst of, as water was always plentiful in the foothills, even in drought years, as it afforded first shot at the largess coming down the steepest drop of all rivers in the country and passing right by us, how convenient.

If you chopped down all of the mostly oak savanna and bulldozed your way through as done in much of SoCal in the midst of my childhood you could subdivision your way to 10,000 here instead of the 2,000ish population presently.

That’s hardly gonna cut it as far as helping out the rest of Cali, sorry bro.

The new tornado alley may become a factor too. This article about the changing tornado pattern puts our situation pretty well:

“We’re in the experiment,” says Walker Ashley, a professor of meteorology at Northern Illinois University who wrote a recent paper on changing tornado patterns. “When we look at the fundamental ingredients that go into creating the severe storm, we are having changes. It’s a question of how much and to what scale?”

As we move past 1.5 degrees C warming, we are indeed living in an experiment since such temperatures have not been seen since humans began agriculture and “civilization.”

We are living IN the experiment. Aren’t we clever?

We are mostly helpless lab animals IN the experiment. The upper class experimenters who have arranged this experiment think their bunkers and escape plans mean they are living aBOVE the experiment. Time will tell if they are right or not.

I live in upstate NY in the center of the state on the PA boarder.I know many people that move south because they didn’t like our high taxes.In a year or less over 90% of them returned. The hot humid weather and low wages were why they returned.I once thought I would move to FL when I retired. After spending a week in July in FL I changed my mind. It is just too hot and humid. I love being outside. It is just too hot to be outside during the day in FL in the summer.Our winters are getting more mild with a lot less snow. This winter we had one “major” snow storm of 3″. No below zero temperatures.This warming trend has been happening here for around 20 years.It has been gradual so most haven’t noticed it. Being a weather observer, I have.Our weather and climate is changing. The seasons are also changing. Winter is shorter and summer is longer.

Sounds a lot like what we’re experiencing here in eastern MA. I barely shoveled this year. I almost miss it!

We do seem to get getting wetter, broadly speaking.

Well, from my Western MA vantage point I agree about the “wetter” part, but up until ten days or so ago we had five feet of snow on the ground. The two falls (1.5 ft and 3.5 ft) that produced it were the first appreciable snowfall all season. We did have 22 below zero (F) in February, but that, too, was an anomaly in an otherwise rainy but quiet fall and early winter. I am ever mindful of what happened when we first moved back to my native soil from SoCal (which is *not* my native soil) 20-plus years ago. We closed on the house on May 15; on May 19 we had 5″ of corn snow. Hmmm, thought I. Maybe this wasn’t such a hot idea after all. Then came the atmospheric rivers, and I felt better about it.

@Jackiebass63 & Johnny GL — same here on all counts, in NE Ohio about 5 miles as the crow flies from the southern shore of Lake Erie.

Hoping against hope our summer will not be too wet, so that we can enjoy Cleveland Orchestra concerts on the lawn at Blossom Music Center…

I have watched the Masters for many years now, and it provides a good example of a change in climate. The tournament is always played on the second weekend in April in Augusta, Georgia. I assume that time was originally chosen because that was the height of the blooming period for the azaleas around the 12th and 13th holes that for decades have given northern viewers a taste of spring weeks earlier than we had up north.

We lived about 45 miles for Augusta a few decades ago, and back then, there were stories about Augusta National packing those famous azaleas with ice to delay the bloom for the tournament week. Now such emergency practices are not enough. The beautiful, blooming azaleas during the Masters seem to be a thing of the past. It has been several years since I’ve seen them in bloom at all round those holes, much less in their peak glory. This year, the coverage intros include a view of Ray’s Creek shot over a foreground of some azalea bushes under pine trees with a few blossoms still showing. But the bushes around the 12th and 13th are just green bushes now.

I have a feeling there will be many things fondly remembered, things more important than a golf course, that future generations will never see, unless through some kind VR perhaps.

Mass climate migration. Hard to fundraise off that. Don’t expect much action from our congress critters. I’ve been begging VPIRG (Vermont Public Interest Research Group) to push our state lawmakers to get in front of this issue, as we will surely be on the receiving end.

Sadly, the author uses what I would consider an overoptimistic timeline. “…The result will be a shambling retreat from mountain ranges and flood-prone riverbeds, back from the oceans, and out of the desert. It will take decades for these movements to coalesce, but once they do, they will reshape the demographic geography of the United States.”” Assuming we have decades seems unrealistic to put it mildly. This diminishes both the potential scale and the urgency required to consider strategies to absorb larger population movements.

None the less, I’m happy to see this subject get some exposure.

The only reason to be in the Central Valley (aside from enormous oil deposits to the south in Bakersfield-adjacent) is Big Ag, which is going to be hit big. This year’s harvests will be awful, with more bad ones to come as growing cycles are out of kilter (not just here-all over the world) and Big Ag is the reverse of buying an IKON season skiing pass, in that Big Slalom wants $700 from me now for something I won’t be able to use for another 9 months from now, while Big Orchard waits 11 months for the next payment with no income in between.

Want a $50k 4 bedroom 3 bathroom house in Cali?

Say yes to Fresno!

p.s.

I left out Big Meth & Big Fentanyl, my bad. Both should have robust growth cycles in Godzone.

Those are two reasons not to buy that nice 5 acre lot out in the sticks and build a house. A half-acre lot is expensive to fence and fit driveway gates, to minimise random trespassers. 5 acre lot periphery? I’d hate to guess.

I’m in surburbia, with a lot onto a main road. I have 3′ high metal bar fencing around teh front, and similar gates (car/ped). Never had any issue with porch pirates, car breakings etc… prevalent in the neighborhood that I’m on the edge of. I’m convinced that the clear demarcation between public/private stops most opportunists.

Buy that nice 5 acre lot out in the sticks and build a house.

Good for you! Good for you! You won this game of life didn’t you. You instead bought a smaller space and put up fences and gates. How special.

This certainly was a conflicted argument. On one hand, people are moving to places the are dangerous in droves, and then it’s written that they’ll all do a 180 and move back to Toledo. I don’t know. That picture of those homes being built in the same spot that homes were destroyed in an earlier coastal storm just about says it all. Ain’t nothing more valuable than waterfront property. I get it, I was lucky to spend a lot of one summer right on a dune overlooking the Atlantic. It was awesome. And, as a friend of mine was bragging about his new life in California, which is pretty nice, he said “It’s so nice to live in a place where it hardly rains.” My response was, well, someday you’re going to turn the faucet, and nothing will come out. He didn’t care.

True Benny. There are no places that are not dangerous. People don’t get it.They keep wanting to move north where it’s cooler. Eventually, moving north becomes moving south.

Formatting error in caption under the map.

Diane Feinstein’s trust just dumped her Aspen property at a $3 M discount below asking. That no one who wants to bribe her stepped up to pay over market says something, maybe about Aspen’s climate future.

Or maybe about Feinstein’s future value.

At her age, Feinstein has a future?

. . . Not to mention the movements of large numbers of people from other parts of the globe due to wars, drought, lack of food, etc. The movement is global just as the problems are global,

Rising sea level does more than affect homes on the coast. Most coastal cities site their waste treatment plants on the coastline (and send the effluent out to sea). Very difficult/time consuming/expensive to relocate a treatment plant that ALL homes in a coastal city depend on.

Detached single-family houses could all install one or another version of Humanure Compostoileting.

https://humanurehandbook.com/

Multifamily buildings/apartments/etc. and multi-user buildings ( offices/factories/etc.) could set up their own multi-user version of Humanure Compostoilet Management. If it hasn’t been designed yet, it could be. It might be cheaper and easier than trying to re-build a current style water-treatment plant beyond the reach of a rising ocean.

I thought this story would be about the real coming Climate Migration: the near-certainty that our current 2-degree Celsius global warming will displace 2 billion people — a quarter of humanity — from the equatorial regions due to heat and drought beginning in 2050. North American sea-level rise and wildfires are small potatoes in comparison.

I have recently left California, where I lived for 65-odd years. I have not found climate impacts to be quite so severe as those with no memory of California 60 years ago. We always had droughts and wildfires. They’re nothing new. Most of Berkeley burned to the ground in 1927. The increasing impacts of these perennial “droughts” and “fires” have been due to over-population and neglected infrastructure, which no one seems able (or willing) to comprehend.

In the community where I lived for 47 years per capita water use was cut by nearly half since 1977 thanks to conservation, but water stress continued due to the doubling of the population during the same timeframe through various forms of uncontrolled migration. In 2021 we lost a thousand homes due to wildfires that burned out of control because over 100 firefighters suddenly became unavailable due to Covid closing the local Fire Camp that had been protecting homes for over 70 years. The western cliffs have been crumbling into the sea for as long as I can remember.

All of this was predictable but exacerbated by over-population. 8 Billion human beings is about 5 Billion beyond the carrying capacity of Planet Earth.

Climate change will force many people to move, but I I think that it will be the refusal to plan and pay for the needed infrastructure building and maintenance; it was PG&E refusing to do the maintenance and upgrading that was the match that started the fires that almost got my Mom with the drought merely being the tinder.

Even with no climate change, I suspect that there would be some migration due to the refusal to impose taxes needed for proper infrastructure; the insistence on doing what people know will destroy an area is crazy kind of capitalism. The destruction of the fires and the floods are like the Dust Bowl. Like the recent fires, it was bad farming practices that created the conditions needed for the winds to become so destructive.

A sound comment, among crazy ones.

I live on a floodplain in Brisbane, Australia. It has gone underwater twice now, in 2011 and in 2022. We built there after the 2011 flood, a house that stands on 3 metre tall stilts. Most of the houses in the area are on 4 metre stilts. In 2022 we evacuated, then watched the floodwaters rise until they were less than a foot below our house’s floor.

Why don’t we move? Because our little, paid-off house is half the price of the houses in the next suburb as a result of the flooding. In order to get off the flood plain we would have to take out a $400,000 mortgage. The price of living mortgage-free is a gamble every decade on whether the water will come up too high.

Of course, we’re still looking to move, because it’s going to be more than once a decade in future. But the price of moving is still too high.

Here are some pictures of our neighbourhood: https://moorookanews.com.au/tag/rocklea-flood-2022/

Finally catching up today, and as I read this I am sitting at a table in a house in the only bright red bright red migration hot spot in Georgia outside of the northern third of the state. Two things about this cause anger. First, that so many people are destroying what was once called The Most Delightful Country in the Universe. Yes, that was colonial hype, but not a lie. And second, that this Most Delightful Country will be uninhabitable for my grandchildren, possibly their children at the latest. All because human beings are sentient only as far as their personal lives carry them. For most of us, that is. As for the brightest of red counties surrounding the City of Atlanta, they will eventually run out of water, too. Not as starkly as Phoenix, but the Chattahoochee River is just about tapped out and ground water is scarce in those parts.

When the Dems* start nuclear war with Russia and China, they’ll rejoice that they finally solved the problems of warming climate and overpopulation.

*to be clear, the GOP will start it to bring on The Rapture.

At least it solves the population problem. I was betting on Covid, but it was a disappointment.

Give it a few decades and combine it with some other things over the same few decades. You should have all the Jackpot you would ever want to see. You might even find yourself taking personal part.

The magnitude of what is coming will be Gibson-esque. THe population movements are going to be like nothing seen since 16th century when Europe repopulated a New World it helped de-populate; maybe even going as far back as the Germanic invasions of the 3rd-6th centuries that destroyed the Western Roman Empire.

In the New World the movement to the poles of vast swathes of humanity will be much less culturally traumatic than what Europe is facing with its new populations coming from totally alien cultures (South Asia, Africa). As for East Asia, forget it. China, Korea, and Japan all are xenophobic societies that will not tolerate mass population influx except at the point of a bayonet.

Besides, China is going to need to find a place for the 300 million Chinese who currently farm the Yellow River basin, because by 2070 the models all predict recurrent multiday outbreaks of wet-bulb temperatures over 38 degrees, meaning 4 hours outside will be sufficient to induce fatal heat stroke. Ditto for India’s northern breadbasket provinces, home to another 300 million.

THis truly is a Louis XV moment. For those wondering, he was the grandson of Louis the XIV (who outlived his sons in his 70+ years on the French throne) who when he was crowned was beloved of the people but by the time he died he was so hated he had to be buried at night. He’s the one who said “apres moi, le deluge”. It was his son and daughter-in-law (Marie Antoinette) who paid the price in 1789.

Anyway, I think the deluge that is coming for the world is the Jackpot (a delightful phrase I was schooled on by Yves, causing me great chagrin as I thought myself a William Gibson student but I had omissions to remedy). Speaking of Gibson, a shout out for The Peripheral on Amazon Prime. Much better than I feared. I hope it leads at last to the Neuromancer trilogy coming to a screen soon ;-)

Back to issue at hand. Bad weather coming. Time to fly the flag upside down or whatever the universal distress code is.

P

wow amazing really for me