Yves here. An analysis of the fallout from California’s big snow, which was generally welcomed for its potential to replenish declining water levels in reservoirs. But a sudden warm spell, which is what much of California will seeing, means a fast runoff, which can produce both floods as well as the water going straight into waterways and therefore into the ocean, as opposed to groundwater and caches.

By Jeff Masters. Originally published at Yale Climate Connections

Floodwaters swallow a county road at California’s Tulare Lake, which has inundated dozens of square miles of farmland this spring. Gov. Gavin Newsom visited the area on April 25 to provide an update on response and flood operations. (Image credit: Office of the California Governor)

-storm category-feature-articles category-weather tag-bob-henson entry”>

As they watch for a spring heat wave set to arrive in the final days of April, Californians are bracing for the first big surge of flooding from a near-record snowpack. Abundant spring sunshine and near-record temperatures in the 80s and 90s Fahrenheit were predicted to stretch from Thursday through the final weekend of the month.

Daily record highs of 93°F in Sacramento and Redding may well be topped on Friday, and some record-warm daily minimums are possible as well. By Sunday, temperatures could approach 100°F in parts of the southern San Joaquin Valley.

Temps 20 deg above normal expected. Shown is the Climate Shift Index from Climate Central. The unusual warmth will accelerate melting of this year’s historic Sierra snowpack, increasing the risks of severe flooding and landslides, particularly in California’s San Joaquin Valley.

— Jeff Berardelli (@WeatherProf) April 26, 2023

The vast bulk of the water trapped in this winter’s snowpack is still in place. As sunshine intensifies from now through June, it will not only warm the air but also prime the snowpack for periods of rapid melting. It’s the timing and strength of these unusually warm, sunny periods — plus the arrival of any final wet storms of the season — that will determine the seriousness of river flooding over the next few weeks. Extended models suggest a cloudy, cool period will likely extend for at least a week or so after the late-April heat abates.

“Any additional early heat waves or major warm rain events between now and early June would still have the potential to cause even greater challenges,” noted Daniel Swain of the University of California, Los Angeles/National Center for Atmospheric Research in his Weather West blog.

The worst of the snowmelt floods are expected to hit the southern San Joaquin Valley, westward and downstream of the southern Sierra slopes where the most extreme snows of winter 2022-23 fell. This spring’s signature flooding has inundated large parts of the 690-square-mile Tulare Lake basin, at the south end of the huge San Joaquin Valley of central California. Once the nation’s largest freshwater lake west of the Mississippi River, Tulare Lake almost completely disappeared in the late 19th and early 20th century as water diversions opened the lake bed up to agriculture.

This year, the lake has reasserted itself, mushrooming to cover more than 100 square miles and triggering conflict across the region. Several farming communities are at risk as well as billions of dollars in agriculture. Parts of the Tulare Lake basin are predicted to remain flooded for as long as two years, as was the case after the back-to-back wet years of 1981-82 and 1982-83 (see below).

“This weather whiplash is what the climate crisis looks like — and that’s why California is investing billions of dollars to protect our communities from weather extremes like flooding, drought, and extreme heat,” said California Gov. Gavin Newsom during a visit to the Tulare Lake basin April 25.

Farther north, the snowpack of the central and northern Sierra isn’t quite as anomalous as in the southern Sierra, but any periods of rapid melt could bring localized river flooding there as well.

Ensemble modeling indicates a greater-than-40% chance that snowmelt will push the Merced River at Pohono Bridge in Yosemite National Park into at least moderate flood stage (12.5 feet) by Sunday, April 30. Most of the valley within the park will close from 10 p.m. PDT Friday, April 27, through at least May 3, according to the park’s website, which added: “It is very likely that the Merced River will reach flood stage off and on from late April through early July.”

Yosemite’s most extreme floods are typically driven not by spring snowmelt but by intense winter rainstorms. That was the case with the catastrophic record floods of January 1997 as well as in February 2023, when the park was closed for weeks after 21 inches of precipitation fell over 21 days.

As announced yesterday, much of Yosemite Valley will close starting Friday, April 28, at 10 pm, due to a forecast of flooding. Western Yosemite Valley will remain open but could close if traffic congestion or parking issues become unmanageable. (1/3)

— Yosemite National Park (@YosemiteNPS) April 27, 2023

One huge plus of the immense snowpack: Water resources will be the most abundant in years. The California Department of Water Resources announced April 20 that it will be able to supply 100% of requested water supplies for the first time since 2006.

Figure 2. A drone provides an aerial view of a cloud mist formed on March 17, 2023, as water flows over the four energy dissipater blocks at the end of the main spillway at Lake Oroville. The California Department of Water Resources announced Wednesday, April 26, that inflows from the lake to the Feather River will rise to 20,000 cubic feet per second on Thursday. The lake was at 90% of storage capacity and was last at full capacity in 2019. Both the main and emergency spillways of Lake Oroville were damaged in February 2017 after heavy rainfall, and more than 180,000 people downstream were ordered to evacuate. (Image credit: California Department of Water Resources)

Recreationalists Beware: This Summer’s Cold Water Will Be Dangerous

Regardless of spring flooding, rivers are expected to run high and cold throughout the summer, and state officials are already concerned about adventurers getting into dire trouble. Even moderately cold water around 50-60°F can produce “cold shock” and greatly compromise breath and muscle control well before hypothermia develops.

The American Heart Association cautions that it’s misleading to assume from polar-plunge events that one can easily survive frigid water, as participants in those events are typically only waist-deep and only for a brief period. The situation is far different when you’re suddenly and fully immersed in cold water — such as after capsizing from a kayak — and you’re likely panicking and gasping for breath. In such a situation, even experienced swimmers can quickly get into mortal danger.

“Cold shock and swimming failure can cause you to drown in a matter of seconds,” warns the National Center for Cold Water Safety in a sobering set of explainers.

A late week warmup will induce a strong snowmelt response for areas near and below 7500-8500 feet. Area streams, creeks and mainstem rivers will run at or above bank full, and will be fast and cold as a result of melting snow. https://t.co/mPY0GJdMVw. pic.twitter.com/dlS1QwVxok

— NWS Reno (@NWSReno) April 24, 2023

Was This a Record Snow Year for California? It Depends

Overall, California’s statewide snowpack ended up among the five heaviest in all winters going back to 1950, based on records from the state Department of Natural Resources. Exactly where a particular year ranks depends on how the records are parsed. This is often the case with global monthly temperature analyzed by NOAA, NASA, and other agencies (as we note each month) and a data-journalism analysis by the San Jose Mercury-News now confirms that the same is true for California snowpack.

While many reports said that 2022-23 had the second-largest snowpack on record behind 1951-52, the Mercury-News pegged 2022-23 as No. five. The journalists noted that the snow data from 1951-52, which ranks first in the state list, included several typically-snow-sparse areas that weren’t normally included in the state survey.

After adjustments, the Mercury-News team found that the top-five snow years since 1950 were unchanged (1951-52, 1968-69, 1982-83, 1994-95, and 2022-23), but they were arranged in a different sequence, with 1982-1983 coming out on top.

The team’s work also reinforced a key point about climate-change analysis: The baseline of what we consider “normal” is shifting. Standard practice is to use the most recent three decades (e.g., 1991-2020) as the best long-term average. When snowpack is instead evaluated against California’s entire 1950-2023 data set, then a long-term decline in snowfall comes into sharper relief.

One thing that’s clear: With water equivalent in snowpack of up to 300% of average, the southern Sierra had its snowiest year in modern records.

What About Next Winter?

There may not be much time for California to dry out before the expected arrival of El Niño later this year. The effects of El Niño and La Niña can vary dramatically from event to event, as emphasized by veteran Bay Area meteorologist Jan Null of Golden Gate Weather Services. Even one of the strongest El Niño events of the past 75 years, 1987-88, was drier than average in California.

In general, though, stronger El Niño events do tend to produce wetter-than-average conditions for California. That’s particularly true for the southern half of the state — which happens to be the hardest-hit area this year as well.

Will El Niño bring more AR storms to West Coast?

— Wonder Woman (@lulabelldesign1) April 20, 2023

“We’ve not seen back-to-back very wet winters in California in the modern era,” Swain noted in a YouTube briefing April 24. “We’ve seen a lot of back-to-back dry winters, but not the reverse.”

California’s statewide precipitation from October 2023 through March 2024 was 27.31 inches, which ranks as the 10th-wettest out of the 128 such periods in NOAA record-keeping. Across a typical state water year (October to September), more than 80% of all precipitation has been received by the end of March.

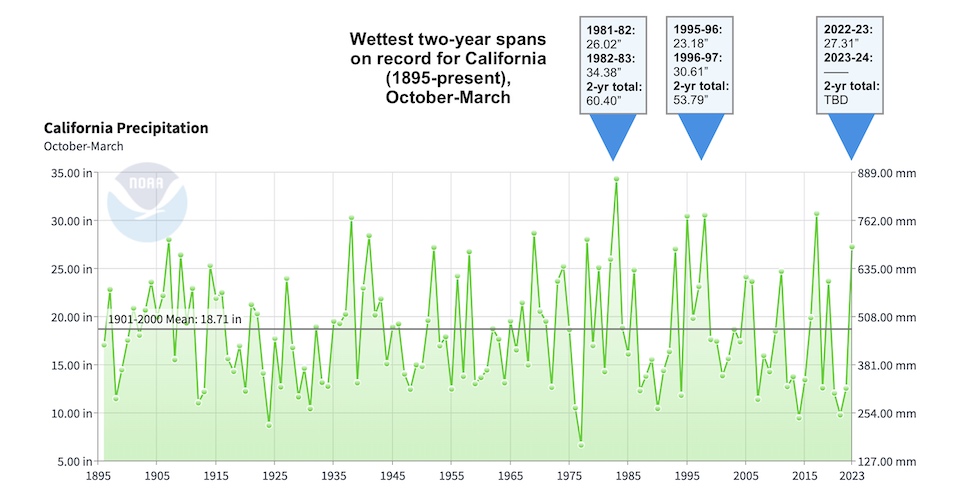

As shown in Figure 3, the wettest two-year period in California records for October-March was 1981-1983. This included the ENSO-neutral winter of 1981-82 and a very strong El Niño of 1982-83. The second wettest pair of October-to-March periods was 1995-97, which adhered to a similar pattern: a cool-neutral winter in 1995-96 followed by the very strong El Niño of 1996-97. The only other comparably potent El Niño event of modern times, 2015-16, was preceded and followed by drier-than-average winters.

If as much precipitation falls next October to March as just fell in those six months, then the period 2022-24 would jump into second place. In order for 2022-24 to hit first place, October 2023 through March 2024 would need to yield 33.09 inches.

Hitting that threshold would be a tall order. Still, for prudence’s sake — and assuming that a robust El Niño arrives as expected later this year — it’s smart to at least anticipate the chance that 2022-24 could approach 1981-83 as one of the wettest two-year sequences in California history.

Jeff Masters contributed to this post.

I did not notice any mention of the storms/super cells that this would potentially create as this snow melts, on an almost daily basis, exacerbated by increased AGW daily ambient temps.

Similar to the summers in Boulder, Co when the ice/snow melts with the sun in the morning on the peaks and then brings daily showers in the early afternoon. With increased temp comes increased energy and with this years snow pack even more moisture and that is a combo for Cell storms et al. As such just worrying about water levels and where its going seems to miss another factor of how this will all change the atmospheric conditions and thus the weather moving forward. This then is just a means to redistribute water around the region in bursts and not just showers, floods.

I raise both paws in the air for more entropy – !!!!!!

>>>I raise both paws in the air for more entropy – !!!!!!

Please! Let’s not. I still remember the flooding in 1982, 84(?), and 95, plus droughts of 76-77 and at least three more since. Then there is the fact that the “normal” years have becoming warmer and have less predictable weather each decade. You live in an area for decades and you can compare changes in the weather. Even the fog seems weakened, less stormy, windy, or cold. Not that much of coast does not get serious fog, it does, but more gentle.

California’s weather has always been unpredictable and the only way that we can have a large population is with the extensive system of dams, canals, pumps, pipes, and reservoirs; all of this requires maintenance and there are always plans, sometimes with the studies and fully written plans done, to expand the system to both fix flaws and for population growth. This all takes money and taxes for something that might not need attention for a decade. Or two. So, it doesn’t get done.

Stuff happens and people complain about the shelved construction projects that did not want to pay for, not being done before the flood or drought. Really, build, maintain, and expand the water system for forty million people including the agriculture without taxes! (Rolling eyes here.)

Wellie at this juncture that might be the only way to take the spin off the ideological Bernays PR Marketing just like with Covid and ugh the unwashed say wtf … ugh the mall is closed and I can’t have that shopping moment or the delivery driver can’t drop of the life changing packet to make my teeth whiter …

No doubt they will be having a helluva problem with massive water run-offs but what would concern me would be mudslides, especially if this were happening above town and villages. There were a series of them about five years ago in California which killed 23 people and hospitalized another 163-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2018_Southern_California_mudflows

In Northern California, the soil is often clay with a thing layer of actual dirt. Unless an area has been farmed (even a long lasting garden), one has to add fertilizer and soil and then mix it well. Had to use a forked or a short three tined blade one time to mix it up.

Anyways, the problem is that most of the plants in the thin layer of dirt is perched onto of the water impermeable clay. This means that the water logged soil is likely to slide off a hill sometimes with a house. Plus all that water rolls off the hills into the valleys. With not that much water being absorbed and the rainy season being only three months, means floods are more common than one would think. If there have been fires, then there are dead plants with dead roots.

I think that the Redwood forest do so well around the Bay Area aside from the fog giving it moisture is that an intact forest with its many plants, fungi, moss, redwoods, and animals recycles all the nutrients. Much more than other forest even though it is a struggle against the frequent fog and rains rinsing the soil of its nutrients. Even with the nutrient free clay with a thin topsoil, the shallow rooted

Redwoods and its ecosystem does just fine. More like weeds, really.

It had been a very wet winter and I still recall the La Conchita landslide in early January 2005. At the time I had an important client in Santa Barbara and regularly drove the scenic coast road along Hwy-101. I knew a guy at my client who lived in La Conchita and what he had to say about his experience of the landslide was harrowing.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/La_Conchita_landslides#2005_La_Conchita_landslide

La Conchita is a tiny beach community nestled within the shadow of coastal hills just across from the ocean. They enjoy a unique micro-clime that amazingly allows for growing Bluefield bananas. I would stop and buy a bunch when time permitted.

With all the snow melt I fear for landslides throughout California.

California has varied terrain and geology. Coast Range (Monterrey to San Diego) is some of the most steep, erodible geology in the state. So the La Conchita and recent Montecito (“little mountain” in Spanish) mud slides are not rare events. Conditions on the east and west side of the Sierra are much different. But flooding without mud is still a dangerous , destructive event.

Also, it is just about the amount of water, but how quickly and where. I think that the flooding in 1982 was because of the solid thirty days of rain after an earlier wet winter with a king tide just all all the local rivers and streams crested. The flooding two years later and in 95 IIRC happened with fairly short heavy dumps that overwhelmed the system as well as isolating Reno and much of Nevada in 95 for just under a week.

Which are just more examples of California’s unpredictability.

Completely different topology these days. Ah the Salton seas goes Jackpot.

The snowpack has been so frozen up top along with temps being on the cold side, that so far there really hasn’t been all that much run-off from the all of the sudden heat here @ ground zero of where the deal is going down, plus next week brings us back to cooler temps, so things seem almost orderly-no extreme flooding.

I’ve seldom seen our reservoir drained so far down as it is now, its ready to take on water being only about 20% full now, down from chock-a-block full 5 weeks ago.

The real issue is in the infrastructure, huge amounts of water are being released into Tulare Lake 24/7 and much work has been done strengthening levees and whatnot, but all the infrastructure of the dams is 60-70 years old with some of the levees being a century or more old.

Should we get another very wet winter next year, Tulare Lake will expand greatly and threaten communities nearby that you wouldn’t think would have an issue, but seeing as very little of the water in the lake percolates into the ground, it’ll be here for a few years regardless of whether next winter is bountiful or not.

An eye popping (last) paragraph from the link embedded in the NOAA tweet.

“One last comment! ENSO has a strong relationship with the global average temperature: in general, the warmest year of any decade will be an El Niño year, and the coolest a La Niña one. Global warming means that we can’t just say “El Niño years are warmer than La Niña,” since recent La Niña years (we’re looking at you, past 3 years!) have featured much higher global averages than El Niño years from the 1990s and earlier. 2022 was the 6th warmest year since records began in 1880, and that was with a non-stop La Niña. If El Niño develops this year, it increases the odds of record-warm global temperature.”

I’ve seen this temperature increase estimated at about a half degree C.

The levee’s along the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers have been poorly maintained for many decades and they have also been weakened by invasive species.

This could get very messy.

It has been said that the extreme incompetence in American governance is recent development, but I would suggest the 1970s as the start. In the 1960s and before, whatever the worth of any water project, it would be funded. After the 1970s, it is almost whatever the necessity of any water project, it will not be funded. Not completely true, but close.

Again, probably when, not if, the levees along those rivers break, just how much wailing will there be about incompetent government, when actually people just don’t wanna pay those taxes and issue those bonds, and then actually spend the billions that should be spent every single year? People do want a functioning water system that protects from droughts and floods while having the necessary water needed for life, don’t they? It is the single most important part of the whole state, even before the electrical grid. No water at all for half the state with much of the rest enjoying more than the occasional flood.

As long as I have been an adult, there has been much wailing about the costs of maintaining and expanding the system, but never about the costs of not maintaining and expanding the system with the largest user of it, the agricultural businesses, which is what they are and not family farms in any real way, wasting much of the water in poor management, bad irrigation techniques, or all the damn almond trees planted.

If we use the internet time machine, we can see a previous cyborg governor was correct about this.

https://archive.internationalrivers.org/resources/new-dams-proposed-in-california-1753

The outright stupidity, manipulation, lying and myopic thinking of his successors is embarrassing. Rather than building this idiotic HSR, we should have been building dams all along. Who’da thunk it? Other than Arnold?

Our current plank of wood governor would rather spend his time in red states trying to get people to move back to CA. If I wasn’t laughing, I’d be crying.

There’s around 1,500 dams in California already whose locations were chosen as they were the best that could be found, do we really want to put some in the 1,501st best location?

I am against building more dams, but the real problem is adequate planning and funding for what we do have. The state builds a dam, canal, reservoir, or levee, but can’t be bothered to maintain it. Then there is the short sighted locals who don’t want to have a desalinated plant, anything really, because maybe it might hurt the fish or lower the property values. Or pay the taxes. However, they scream when there is not enough or too much water!

If you want to live anywhere at a certain level of comfort and safety, then you must build, modify, maintain whatever is necessary. This is true at any level of society or civilization. Too many Americans chose to believe in either their Rugged Individualism because Government Is Evil or Thinking Good Thoughts about Mother Earth while sorting their recycling will suffice.

Apologies for the ranting. Just seeing my state doing dumb sh** because reasons is really annoying and that is not mentioning my past, current, and future quality of life is affected by these clowns.

Dams along the western slope are administered & run by the US Army Corps-not the state

I’m only really hep to our dam and reservoir here, and can tell you that improvements have been made in increasing capacity and huge fuse gates were also installed, all since the turn of the century.

The boogeyman with these dams is that they all were built eons ago and silt has had a long time to build up.