Yves here. This post about J.M. Barrie, of Peter Pan fame, attempting to soften opinion in England about Russia in the wake of the Soviet Revolution is oddly touching but also sad, and I am absolutely not a Peter Pan fan.1 This vignette and its related threads (the very delayed Russia uptake of Barrie) is a weird reminder that as technology and travel have in theory made the world smaller, too many (out of reflex? out of perceived threat to their authority or commercial interest?) find ways to throw up new hard barriers in place of distance and limited information and cultural exchange. Humanity was supposed to advance towards more tolerance and prosperity and with it, less conflict. That promise was seeming to be realized as the Industrial Revolution advanced in the 19th century and Europe stayed free of major war for nearly 100 years. Then the Great War brought and end not just to that but to nearly all of what was left of the old aristocratic order.

So I hope you welcome this break from our usual programming.

By John Helmer, the longest continuously serving foreign correspondent in Russia, and the only western journalist to direct his own bureau independent of single national or commercial ties. Helmer has also been a professor of political science, and an advisor to government heads in Greece, the United States, and Asia. He is the first and only member of a US presidential administration (Jimmy Carter) to establish himself in Russia. Originally published at Dances with Bears

Once upon a time, one of the leading literary figures in the UK defended Russian culture by staging a play in a London theatre in 1920 and again in 1926. J.M. (James) Barrie, famous then and now as the creator of Peter Pan, was the playwright; the play he wrote was called “The Truth about Russian Dancers”.

Not one Englishman or Scotsman (for that was Barrie’s race) dares to do such a thing today.

Barrie’s play followed after the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 and the attempts by the British government in military operations, economic sanctions, and propaganda to attack the new Kremlin regime, kill Vladimir Lenin, and replace the Red government. These military operations didn’t end until the British army withdrew from Russia in September 1920, five months after Barrie’s play had concluded its popular stage run.

According to his script, the fantasy and beauty Barrie characterised as the Russianness of Karissima, the heroine of the play, and her company of dancers is pitted against the unimaginativeness and rigid conformity of the British. And so it is today – that is, if you believe in Barrie, Peter Pan, and their lost boys.

Very well known in Russia as a prima ballerina in her time, Tamara Karsavina, played Karissima, the lead in Barrie’s play “The Truth about Russian Dancers”, but the play itself was not noticed in Russia at the time; it was subsequently forgotten in England. It was rediscovered in English by Olga Soboleva in an academic publication in 2015. This was picked up in Russian in 2019.

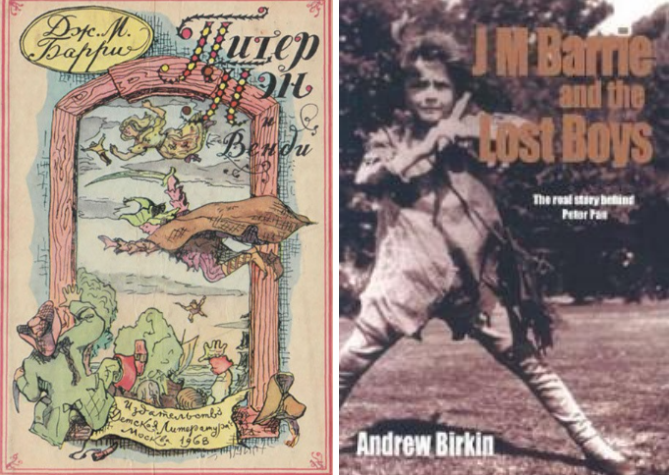

Peter Pan first appeared in Russian translation in 1918, after Lenin had begun to consolidate his power and the tsar had been executed. It was fifty years before a second translation was published by a Soviet house in 1968; a third followed in 1981. Since the end of the Soviet Union, there have been twelve fresh translations. The 1981 translation by Irina Tokmakova can still be purchased here.

A lengthy history of Russian as well as Soviet interpretations of Barrie’s creation of Peter Pan and its meaning appeared in 2017. It was written by Alexandra Borisenko, a professor of philology and specialist in English literature at Moscow State University. She understood that Barrie was writing autobiographically; that the Peter Pan story was much more than a fantasy; and that the character had appeared many times in Barrie’s work before Peter Pan was named and became famous. “He experienced many losses and tragedies, and this wound permeates almost all of Barrie’s texts, including the tale of Peter Pan.”

Mistaken as a fairy tale for children, Barrie had written his story for adults about children; that’s to say, the loss of children. “Barrie was thinking about childhood all his life,” Borisenko concluded, “and constantly returned to this topic in his work: the eternal childhood of those who died before they could grow up; the eternal childhood of those who cannot grow up; eternal childhood as a refuge and as a trap.”

“Ridiculous Barrie-ness”, wrote the book critic at The Times in praise of an earlier version of this theme published in 1902. “Utterly impossible, yet absolutely real, a fairy tower built on the eternal truth… Mr Barrie has given us the best of himself, and we can think of no higher praise.”

“Peter Pan,” Borisenko wrote, “came to Soviet children’s literature relatively late, in the 1960s. For quite a long time the fairy tale in the Soviet Union remained under suspicion — it was believed that unbridled fantasies were harmful to children. Peter Pan was discovered for the Soviet reader almost simultaneously (and independently of each other) by two of the best translators of English children’s classics, Boris Zahoder and Nina Demurova. Boris Zahoder translated the play — at first his translation was staged by MTYUZ [Moscow Young Viewers’ Theatre], then in 1971 he came out with Barrie’s book. As always, Zahoder translated quite freely, with great passion and sensitivity to the text.”

“In the preface, he explains the freedom of handling the text with the interests of the addressee –the child: the translator tried to be as close to the original as possible, more precisely: to be as faithful to him as possible. And where he allowed himself small ‘liberties’ — these were liberties caused by the desire to be faithful to the author and be understandable to today’s young! — to the viewer. The first translation of the story ‘Peter Pan and Wendy’ had to lie in the desk drawer for ten years. Nina Demurova saw the English ‘Peter Pan’ in the early sixties in India, where she worked as a translator. She liked the illustrations by Mabel Lucy Atwell, so she bought a book and sat down to translate it. It was her first translation experience, and naively she sent it to Detgiz [Detskaya literatura, ‘Children’s Literature’] publishing house. To no avail, of course. But ten years later, when Demurova became a famous translator thanks to her translation of Alice in Wonderland, she received a call and was offered to publish ‘Peter’.”

“Detgiz was going to severely censor the text. Actually, this should have been expected: it is difficult to imagine a work more distant from the Soviet concept of childhood (joyful, cheerful, creative and devoid of ‘tearful sentimentality’). Children’s literature was censored no less than adult literature, and for the most part the rules of the game were known to everyone in advance. The translator himself cleaned up and smoothed out in advance what would surely ‘not be missed’.”

Left: the 1968 Russian translation by Nina Demurova of Peter Pan and Wendy. Right, Andrew Birkin’s biography, with additional material and photographs from the Yale University Press edition of 1986-2005: In Russia two other publications about Barrie, his life, his stories and Peter Pan’s interpretation are Nina Demurova, Peter Pan in Russia.; and Chris Routh and Nina Demurova, In the Neverland: Two Flights over the Territory, 1995.

Almost no Russian knows of Barrie’s play about Russians; the same for the English biographers of Barrie and of the Peter Pan story. Andrew Birkin, the most sensitive of Barrie’s biographers and the maker of a BBC film about his life, failed to mention Karsavina or Lidia Lopokova, another Bolshoi Theatre ballerina whom Barrie knew well; his play was originally written for Lopokova. The J.M.Barrie website’s database also ignores the Russians.

Birkin’s biography of Barrie is the story of how the man turned everything he suffered of loss into the love that everyone – almost everyone except George Bernard Shaw – recognizes in the original play, Barrie’s books on Peter, and in the film about Barrie. In a first draft of his personal dedication of the play to the five boys of the Llewellyn Davies family who had inspired it, Barrie wrote: “this dedication is no more than giving you back yourselves.” What has happened is that in a way no one can anticipate in advance, what Barrie has done is to give us all back ourselves.

The moment this was recognized by the opening-night audience at the Duke of York’s Theatre, on St. Martin’s Lane, London, came when Peter Pan, addressing the audience over the footlights, asked them to signal if they believed in fairies by clapping their hands. The response was tumultuous then, December 27, 1904, one hundred and nineteen years ago. It still is, if you can read or imagine the original play – and not the Disney and other bowdlerizations which have tried to make money by replacing and puerilizing it.

When Mark Twain saw it in a Broadway theatre in Manhattan, he wrote privately to the actress who played the lead: “Peter Pan is a great and refining and uplifting benefaction to this sordid and money-mad age.”

The suffering of ordinary lives was concentrated beyond extraordinary in the case of Barrie and the Llewelyn Davies boys – mortal accidents skating and crossing the road; terminal cancer of their father and mother; one death in war; suicides by drowning and by train, etc. If none of this misfortune is familiar to you, stop reading at this point and count yourself to have been so lucky, so far.

“The whimsicality that so many people have found intolerable in J.M.B’s work,” Peter Llewelyn Davies wrote in 1950, “and which was no doubt of the essence of his genius and primarily responsible for his achievements and success, was something almost beyond his control as soon as he had a pen or pencil in his hand. His conversation was often on a much higher plane, and doubtless rose to its highest in his talks with the dying Arthur [Llewelyn Davies, Peter’s father].”

The script, stage set and costume designs, director’s records, and photographs which the Victoria and Albert Museum keeps in London of “The Truth about the Russian Dancers” – filed in the archives, not on public display — is summarized in the museum’s published note. The play shows “how Russian dancers love, how they marry, how they are made, with how they die and live happy ever afterwards… the Russian dancers are not like ordinary humans. They are called into being by a master spirit and can only express themselves through their own medium: they find it so much jollier to talk with their toes. Russian dancers are not ordinary mortals; they are made by their maestro, and when they give birth to a child – also a Russian dancer – it costs them their life. In this case, however, the Maestro seems to have had a generous heart, or to have repented of early wrong doings, for he brings Karissima back to life, and lies on the bier in her place.”

Left: Tamara Karsavina in the death dance from the play, March 13, 1920. Right: Karsavina takes a bow, a photograph in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum. The play ran for an initial five weeks, and was revived in July 1926. In the present circumstances it could not be revived because no Russian dancer or musician would be allowed by the British government into the UK. The Bolshoi Theatre has recently complained that foreign-made ballet shoes, pointes, have been sanctioned, and that Russia’s ballet dancers must dance on without them. And that’s not all. Leading Russian ballet directors and choreographers working abroad have been forced out of their jobs.

In a few days’ time in May, it will be the 102nd anniversary of the death in 2021 by drowning of Michael Llewelyn Davies, one of the lost boys from whose combination Barrie had created the story of Peter Pan; Michael was the one dearest to Barrie’s heart after George, his brother, had been killed on the Ypres front on March 15, 1915. “Such have been there will be such again,” he wrote later, “but not for us”. Michael was “the lad that will never be old.”

Barrie was the greatest writer there ever was of the love known to the Greeks as Pothos, the god of longing for what is lost.

There have many poets of the same in short bursts. But none for as many times, for as long and as sad as Barrie. Because of that, Barrie was tolerant and civilized as nobody writing English in the UK against Russia in this war can approach, or even comprehend. Not one Englishman left (or Scotsman).

NOTE: The lead image is a Russian forest with two bird-men, a stage set by Mikhail Larionov for Anatoly Lyadov’s ballet titled Russian Fairy Tales. Lyadov tried composing his ballet between 1916 and 1918, but didn’t finish. The bird-men never appeared on stage.

____

1 I did not enjoy being a child. So romanticization of children, even when I was little, didn’t sit well with me.

Peter Pan was atypical Barrie and I also am indifferent to it. Most of his plays were social commentary made bearable by some humor. The Admirable Crichton, for example, holds up well as commentary on class and meritocracy – obviously the butler is superior in knowledge, intelligence and skills to his betters but returns to servitude once back in our civilization.

I was unfamiliar with the Truth About Russian Dancers and may read it.

Article highlights some little-known facts that the UK (aided by the US) invaded Russia to overthrow the Bolsheviks. The blockades, “sanctions” and other acts of war were put in place. Eventually this led to the Red Scare 1.0.

The historical irony is that today Russia is not Bolshevik, nor commie, yet we have Red Scare 3.0. The cultural and economic boycott of Russia and all things Russian is almost unbelievable. As the article points out, the anti-Russia hysteria is even worse now, than it was in 1920.

The anti-east, anti-orthodox, anti-Russian sentiments have a long history in which to draw from.

There has been a “negative identity principle” at work in Europe for many centuries: one could argue it goes back to Roman times with the Latin West and Greek East. Then in 1054 the Great Schism of “Christendom”, followed by the Crusaders sack of Constantinople in 1204. This was the final blow to the Eastern Empire. (not the Muslims but fellow “Christians”destroyed the place)

The “east” was considered somehow heretical, and sinister. Then, later the East became “backward” and barbaric, compared with the ‘civilized’ West.

Fast forward to the 20th century. Nazi ideology considered Russians as uentermenschen. The idea to invade Russia (Drang nach Osten), exterminate the population (creating “lebensraum”) and resettle Russia with Germans has largely been forgotten. Churchill’s own writings show that he wished Hitler to destroy the USSR, and really considered “Bolshevik Russia” as the real threat.

In this historical context, the recent anti-Russian propaganda is very disturbing. It can be seen as based on deep-seated cultural and political biases (and outright falsehoods). We are supposed to rejoice about “killing Russians”, boycotting all things Russian etc. This is (almost) surreal but has history to draw from.

The present scare has permeated through more social strata than in 1917, when only the elites were panicking…

The force and penetration of propaganda is also greater now…

I have to say that I find all this anti-Russian propaganda and pervasive hatred of all things Russian very worrying. The fact that it can be turned on so easily makes me feel that there is something deeply wrong with ‘western’ humanity and ‘civilisation’ (apart from all the other obvious symptoms such as ‘liberalism’, scientism, materialism etc.). A lot of this ‘wrongness’ seems, to my mind, to be associated with the English ‘upper’ classes, and the spread of their mercantile attachments throughout the western world. I imagine there are books out there which may make this case more clearly, but I haven’t read them (yet, anyway), and as far as I can take this, it’s only a ‘feeling’, prompted by reports similar to those such as in ‘JonnyJames’s post above with regard to Churchill. Or perhaps it’s this (although Russia is not ‘poor’ or ‘mean’):

“This disposition to admire, and almost to worship, the rich and the powerful, and to despise, or, at least, to neglect, persons of poor and mean condition, … is, … the great and most universal cause of the corruption of our moral sentiments.”

Adam Smith – The Theory of Moral Sentiments, 1759

It is, basically, a reheated ethos from 2500 years ago: light versus darkness, civilization versus barbarism, garden versus jungle. Or as they said ways back when, Iran versus Turan. Interpretable either as “land of Aryans” versus “land of Tur” or more prosaically land of the noble versus the land of the darkness.

Center has always looked upon the periphery as more or less deplorable, but when it feels threatened – and especially when it’s about to collapse – it turns into pure hatred of the barbarians hordes coming to take away and despoil all that is good and holy.

“Humanity was supposed to advance towards more tolerance and prosperity and with it, less conflict.”

I’m not sure where the “supposed” actually comes from, although surely it would be most anyone’s hope.

That we don’t have this means what? Who endeavors or benefits from this not being achieved?

Certainly more tolerance was a hope of the Enlightenment. As indicated, the absence of major wars in Europe in the 19th century, after their long history of conflict, would also seem to demonstrate that ample opportunity for wealth creation at home would make pillaging your neighbors less attractive.

Last Christmas was the first where I very definitely didn’t hear ‘Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairies’ (Tchaikovsky) anywhere. I adore Russian ballet, and the ballerinas and danseurs of today are incredible.

There are Youtube videos of them that blow my mind, especially the graceful women, who are now incredible body freaks, with workout routines and diets that make them athletically superior to those of yesteryear.

A ballerina has to be a dancer, a thespian, a gymnast, and a contortionist, all at once. They are some of the most put-upon artists I can think of because of it. Watching Svetlana Zakharova dance as Nikiya in ‘La Bayadere’ is amazing. She can leap like Michael Jordan and toss her legs out in a perfect mid-air split, her abdomen rippling but not overly muscular, her poses perfect.

And the new kids are on the way, like Elisaveta Kokhoreva and Maria Khoreva, two very different dancers. The first has just been announced as new 2023 Bolshoi prima, and she’s delightful, a picture of grace and beauty. The second has her own channel, and tends toward the athletic a bit much for me, but she has workout and stretching videos that are crazy. Excellent technique, tho.

Anyway, I’m angry about this kind of thing, because these fantastic Russian beauties will never be seen by anyone I know. Benign art culture and politics must be separated, like we might do with art and artist. Jeez, I’m even able to do that with Hitler, whom I don’t think was terrible at art. Maybe if the world accommodated art more, he mightn’t have ended up a murderous dictator, but a simple painter of Vienna beer Kellers.

Finally, I’ve been writing a novel for four years, and one of my mains is an expat Russian from the nineteenth century. I am about to finish it, and I’m just waiting for the horrors. “We’re not doing Russians at this time. Rewrite him as a Belgian or something, and maybe get back to us.” If I see a lot of that, maybe it’s just time to end it all. America wants to kill artists, or subsume and consign their work to screens.

My grandfather was of loyal orange stock from Northern Ireland, living in Canada when he signed up to fight for king and country. In 1918, after having survived Passchendaele and all sorts of horrors, the British government announced that any unmarried veterans of WWI would be sent to fight with the White Russians against the evil Bolsheviks.

Grampy quickly married and shipped back to Canada.

I tried to find a copy of The truth about Russian Dancers on all of the “rare books” for sale sites with no luck. It is also not found on the sites with extensive book pdfs.. Any thoughts about how to find a copy to read?

Try WorldCat to find a library edition https://worldcat.org/title/1389212

and there is a lovely you-tube of the Bax music that was written for the play: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l4rXbSHvQLE

Some great addition detail here (an old school blog!):

http://fierychariot.blogspot.com/2007/06/j-m-barrie-and-russian-dancers.html

Including a connection to John Maynard Keynes. Wild stuff.

Thanks!

I will try to work though interlibrary loan.

Sailor Bud I share your love for ballet and the physical achievements of the ballet dancer.

Having studied it I’m also aware of the superiority of ballet as a personal physical practice – it’s so incredibly difficult on every level.

I don’t wholly share in your romantic view of the professional ballet dancer. My disagreement is from the perspective of the physique ‘suffering for its art’.

What is required of a professional ballet dancer to excel ongoingly, unequivocally wreaks the body, permanently. You’ll find retired dancers are forced to maintain intense daily regimes of stretching just to ensure they can continue functioning and don’t sieze up.

Which equates to chronic stress. Their art is achieved through endured off the charts levels of physical and psychological stress for years. On the other hand indeed its why and how they deserve our admiration. A double edged sword.

I don’t share the romantic view of classical dance at all. Trying to live up to the inhuman esthetic standards of the art form just takes too high a toll on too many ballerinas to consider it an acceptable price to pay. I spent five years in that world as a stage manager and husband, and in that short time I saw enough permanently deformed feet, life-altering (sometimes life-threatening) eating disorders, and discreet psychiatric hospitalizations for classical ballet to have lost any superficial appeal. People who wax rhapsodic about the beauty of classical dance remind me of men who call boxing the “Sweet Science”: in order to admire the artistry, they have to willfully ignore the sometimes severe damage it does to so many artists.

You’re welcome to lump me in with the boxing fan. I won’t complain because it would be stupid to argue, but your last statement – that we willfully ignore it all if we wax rhapsodic about its beauty – is simply wrong, and you didn’t ask me, either. My first college roommate was a ballerina. It’s how I ever came to love the art.

One of the dancers I’ve named, Khoreva, has videos openly discussing it all, and she’s hardly the only one. Her feet look completely messed, and she’s still young. She has a clear passion to continue doing it, tho.

As for another, there is a fascinating video called ‘Inner: Svetlana Zakharova,’ that shows her talking about how it will all be daily pain, always. It is sad as Hell. She doesn’t look or sound happy in any of it. What to say? I still think she dances beautifully, and I always will. I don’t ignore it, though, and I still love it, and always will.

As Savita said, it’s (part of, for me) why and how they deserve our admiration. Baby bathwater me as much as you like, tho. It doesn’t matter.

Most of my classical dance experience was in the context of an internationally renowned ballet company. A minimum of 50% of the female dancers had a MAJOR eating disorder (straight anorexia or alternating bulimia and anorexia), driven by the pressure to “make weight.” For me, the coup de grâce came when when a recent, very sweet, very “normal” teenage addition to the corps f*cking died from a Karen-Carpenter-style anorexia-induced electrolyte imbalance. If you find that an acceptable price to pay for your enjoyment of the art form, I can only quote Maximus Decimus Meridius (Russell Crowe) sarcastically addressing “circus” fans in the movie Gladiator: Are you not entertained? Are you … NOT … ENTER … TAINED?

It’s a separate issue, but I agree. I hinted at it with my ‘most put upon’ comment, where I invite people to investigate the horrors and the glories themselves.

I’ll still ‘romanticize’ beauty if I see it, because those body things exist in most physical arts. I’m a pianist, and have seen mountains of people with physical problems from the evils of the classical literature. I’ve had them myself. The history is full of pianists ruining their hands on single pieces, even, or hurting them, as with Scriabin hurting himself on Balakirev’s Islamey. It’s not ‘the same thing’ exactly, but it’s true of nearly all physically taxing art, particularly those requiring extension of flexibility, combined with virtuosity.

Ah, and I thought the Manichean Heresy had been exterminated, but it still simmers in all its binary glory. /snark

PCM and Sailor Bud, love your responses thanks so much. PCM especially grateful for your acute validation. Boxing ‘ the sweet science’, what a grotesque phrase! But I can think of one boxer that deserves the reference. While not being into fighting at all, for some reason I wanted to see the reason for the reputation surrounding Floyd Mayweather. ‘The greatest defensive boxer of all time’. It’s the dancer in me that was compelled. I watched a compilation on Youtube. His ability to move around the opponent was staggering, unhuman, like a amazonian python. I was literally laughing my head off, so astounded was I, seeing him in action for the first time.

And I can recommend a documentary about legendary ballet dancer Sergei Polunin, simply titled ‘Dancer’. It sounds similiar in tone to the film Sailor Bud described but more about the emotional toll, instead of physical.