Yves here. This post is written in a clinical manner, but it nevertheless attempts to assess the impact of the effort of the EU to divorce itself economically from the Russia. This looks to be a fair-minded effort, given the resistance to candor about sanctions blowback. For instance, it finds that Europe does not have ready substitutes for 3/4 of imports from Russia, mainly energy and “other critical and strategic raw materials.” Oopsie.

By Francesco Di Comite, Chief Economist team member, DG GROW (Internal market, industry, entrepreneurship and SMEs) European Commission and Paolo Pasimeni, Senior Associate Brussels School Of Governance – Vrije Universiteit Brussel; Deputy Chief Economist – DG Internal Market and Industry European Commission. Originally published at VoxEU

The European economy was still recovering from the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic when the Russian invasion of Ukraine triggered new economic disruptions, highlighting the importance of exposure to geopolitical risks and the vulnerability of international value chains. This column examines the exposures and dependencies of the EU economy at the time of the invasion and the massive adjustment taking place to decouple from Russia. While the openness and flexibility of the EU economy allowed businesses to reorganise their supply chains in a relatively short time, this adjustment may have structural impacts on the competitiveness of European industry.

The EU is one of the main actors in global trade and one of the driving forces of international value chains integration. This has allowed the European economy to reap the benefits of globalisation, specialise in high value-added processes, and increase its productive efficiency. Yet, a tension between efficiency and resilience has emerged in recent years. When in early 2022 the European economy was still recovering from the impact of the pandemic, the Russian invasion of Ukraine triggered new economic disruptions, highlighting the importance of exposure to geopolitical risks and the vulnerability of international value chains.

In this column, we analyse these vulnerabilities and focus on the endeavour of the European economy to decouple from Russia. In doing so, it complements a number of recent studies that have analysed the implications of the sanctions and post-invasion disruptions in Russia (Demertzis et al. 2022) and across the globe (Borin et al. 2022, Langot et al. 2022, Attinasi et al. 2022, Ruta 2022, OECD 2022, IMF 2022).

Decoupling from a structurally relevant trade partner requires multiple efforts. In a new paper (Di Comite and Pasimeni 2023), we illustrate the large ongoing adjustment that the European economy is going through, identifying exposures and the unwinding of dependencies in the course of 2022. We look at them from a risk-assessment perspective, focusing on dependencies and related vulnerabilities, especially on imported commodities.

The significance of Russia as a trade partner for the EU was amplified by the concentration of its input in key supply chains. Energy-producing commodities and other critical and strategic raw materials (CRSMs; see European Commission 2020, 2023) have a low degree of substitutability and a limited number of global suppliers. They account for more than three quarters of all EU imports from Russia. For the majority of these inputs, imports from Russia have been falling significantly in the course of the year, signalling a reconfiguration of supply chains towards alternative sources.

On the Russian side, the EU was the major trade partner, providing a vast variety of investment goods and high-tech products. The sectoral structure of trade suggests that China represents for Russia a possible alternative to the EU, because it is a major exporter in those sectors for which the EU was one the main partner for Russia. These are typically manufacturing of machinery and equipment, computer and electronics, fabricated metal and plastic products, chemicals and textiles.

Gross Trade flows

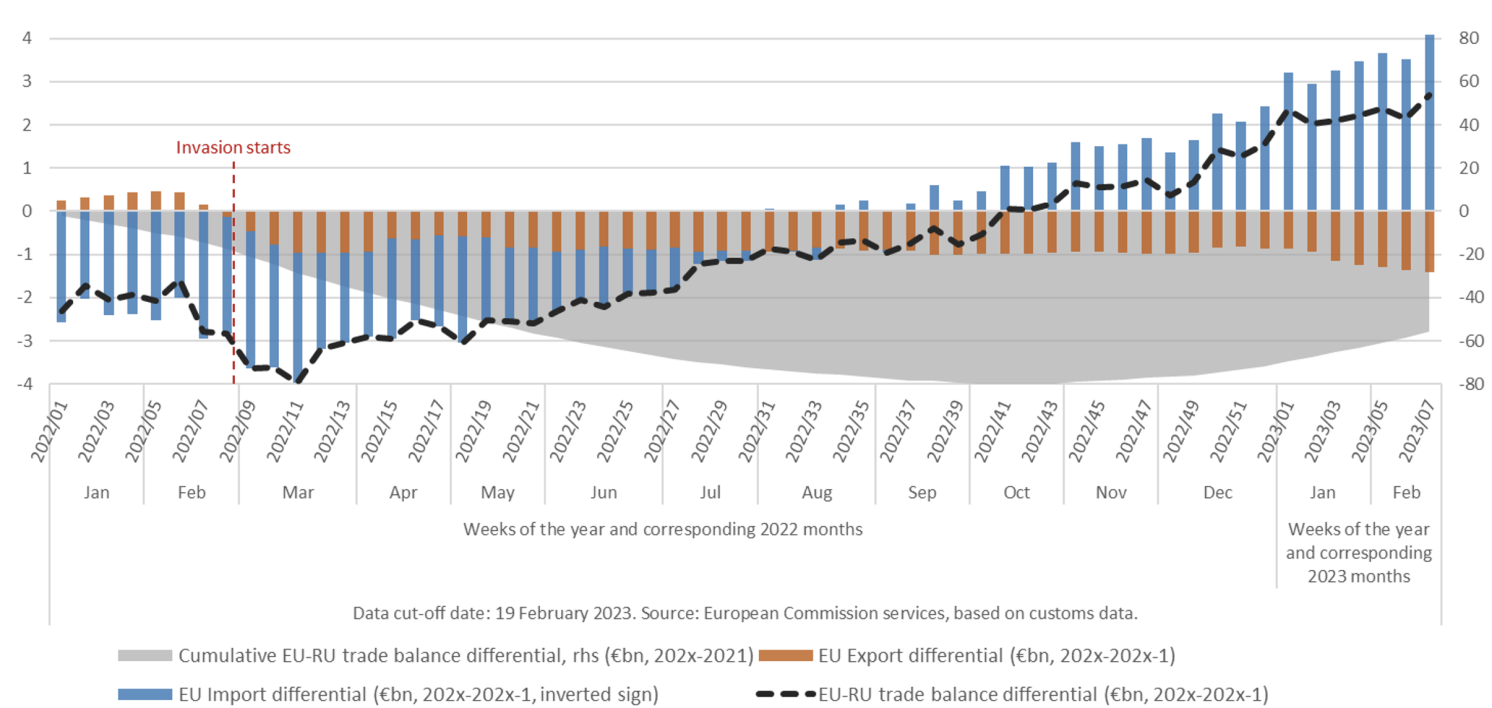

At the time of the invasion, the EU was highly exposed to the import of Russian commodities, notably fossil fuels and critical raw materials, but data show that it gradually managed to reduce such exposure over the course of 2022. Using a unique, high-frequency dataset based on customs data, we document a sudden and sizeable reduction of EU exports to Russia just after the invasion. Imports adjusted more gradually because of the low degree of substitutability of fossil fuels and critical raw materials. Moreover, they became much more expensive in the weeks after the invasion.

This has led to the EU accumulating an additional bilateral trade deficit vis-à-vis Russia of roughly €67 billion in 2022, compared with the same period in 2021. Such additional trade surplus for Russia corresponds to roughly 3.3% of its GDP and has probably been one of the factors behind the initial strengthening of its currency. Yet, with a sustained reduction in volumes of fossil fuel imports, by the end of 2022, the EU managed to stop, and even started to revert, this deficit accumulation vis-à-vis Russia.

Figure 1 Change in the EU–Russia trade balance with respect to 2021 (€ billion, five-week moving average)

Strategic Dependencies

In recent years, the European Commission has proposed methodologies to identify ‘strategic dependencies’ – products for which the EU relies on a highly concentrated set of foreign suppliers and has limited domestic production capacity (European Commission 2021, 2022) – and CSRMs – important commodities with a high supply risk (European Commission, 2020, 2023). We were able to identify 12 strategic dependencies vis-à-vis Russia (of at least €100 million in imports) and 19 CRSMs. With a few exceptions (nickel mattes and fuels for nuclear reactors), imports of products for which the EU had a dependency on Russia decreased significantly over the course of 2022, on average by 20 percentage points in market shares. The supply of 11 of the 19 CRSMs decreased by 50% or more.

Figure 2 EU dependencies on Russia: Market share changes between 2021 and 2022

Energy

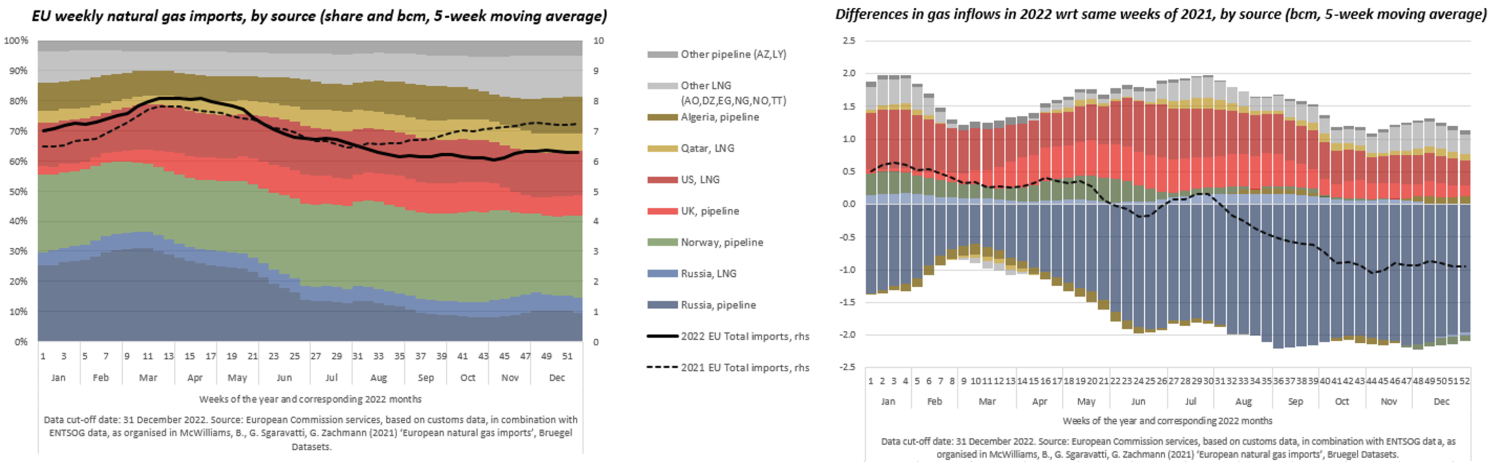

Energy products, and fossil fuels in particular, were key inputs for the EU economy sourced from Russia (€110 billion in 2021, 74% of the total energy import). Pipeline gas imports alone account for more than one third of all EU energy imports from Russia, and in February 2022 they accounted for more than 30% of all EU gas inflows. Since today gas is the marginal source used to balance the internal energy system, its price evolution determines the prices of the entire EU energy and electricity systems.

The total volume of pipeline gas import from Russia fell by one third in 2022 compared to 2021, whereas overall EU imports of gas in 2022 remained at roughly the same level, thanks to diversification into alternative sources of liquefied natural gas (LNG) – the US in particular. However, LNG import prices are 46% more expensive than pipeline gas import prices, with Russian LNG being the most expensive (Russian LNG import prices in the EU being 60% above average gas import prices) and US LNG being only slightly less expensive (50% above average gas import prices). A structural shift from pipeline to LNG gas sources may thus imply for the European industry a considerable loss of competitiveness.

Figure 3 Weekly natural gas flows (pipeline and LNG) into the EU by source in 2022 and 2022-2021 differentials

Conclusion

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has led to a permanent adjustment of EU supply chains, with a progressive decoupling from Russia. On the one hand, the Russian economy is gradually losing one of its main foreign sources of income. The extent to which Russia can substitute the EU with other trade partners remains an open question. On the other hand, the European economy is performing a sizeable adjustment in its supply chains, especially for key raw materials and energy products.

All in all, the European economy demonstrated substantial resilience to the shock. Our analysis shows that the openness and flexibility of the EU economy allowed businesses to reorganise their supply chains in a relatively short time. Yet, this adjustment can have structural impacts on the competitiveness of the European industry, given the need to turn to second-best supply chain configurations. If persistent, the relatively higher price of key inputs may result in losses of market shares, in particular in sectors key to the green transition.

The unprecedented nature of this shock has prompted a reflection in terms of resilience, of business models, and of supply chains that is not limited to short-term fixes. This crisis stress-tested the resilience and ability to adjust of the European economy. The challenge is now to ensure the sustainability and competitiveness of the emerging supply chain configurations.

See original post for references

In 14 short paragraphs, there are 3 instances of “Russian invasion of Ukraine” and 5 instances of “invasion”. This may be a fair -minded effort with respect to the effects of the sanctions, but it’s necessary still to assure readers 8 times that none of this can be discussed in terms of bad policy decisions in the west.

Thank you, Yves.

It would be interesting to get data and commentary on and from countries and activities that are more integrated with / reliant upon Russia.

In some, if not many, cases, such reliance has come as a surprise. A few weeks ago, the CEO of https://www.creedfoodservice.co.uk/, a family owned catering and catering supplies firm, admitted on local tv news that he did not realise how much his supply chain depended on inputs from Russia. That was before the stresses from Brexit and the pandemic still playing out.

Having worked for HSBC in some of the former Warsaw Treaty Organisation states, 1999 – 2006, I am surprised how little people know or pay attention to how their firms, industries and micro economies work.

Cracks are also widening within EU solidarity with Ukraine. Both Poland and Hungary have banned the import of Ukrainian grain, on the grounds that their own farmers are being undercut by the much cheaper grain from Ukraine. However the high and mighty EU in Brussels has announced that only they can make such policy decisions and they intend to continue to allow Kiev to export grain to help their war effort. It will be intriguing as to how this will play out. Romania and Bulgaria have also hinted they will join the grain ban.

It demonstrates the ability of someone, anyone, to buy stuff required at a price 50% plus higher than optimal.

This is ‘resilience’. This ignores some stuff that you probably just can’t buy elsewhere in sufficient quantities to keep going at previous levels.

Its a picture of managed de-industrialisation, with a ‘winner’, the location of which is several thousand’s of miles west of Europe. Plus of course China who now has a buddy nation with loads of resources with one less competitor buyer.

I can see the advantages to most others of the European policy , but its pretty disastrous for its citizens, which will increasingly be felt over future years. Of course its totally in line with ‘net zero’ policies which now hide behind the myth of protection from the Russian barbarians.

It also appears to ignores stuff that the EU can’t sell elsewhere in sufficient quantities to keep an industry going.

I think economic theories promoting degrowth will grow in popularity as deindustrialisation progresses. There will be ample argumentation that lower material prosperity is a path to more happiness. Just like in Bhutan, which prides over its national happiness index instead of any GDP growth. Of course it is a poor country, but that doesn’t matter as long as the index shows people are happy.

(the) people (who count) are happy.

Those Bhutanese Nepali speakers who still live in Bhutan (about half were expelled in the 1990s) continue to suffer discrimination in almost all aspects of their daily lives, including in education, health, employment, and land ownership. But maybe it’s like the American Blacks, whom according to the Southern Baptist Church, were happier under pre-civil war slavery than in modernity, so it probably should be the people who do the counting are happy they count. Hard to fill up 3/5 with full happiness.

The extent to which Russia can substitute the EU with other trade partners remains an open question. Versus: This crisis stress-tested the resilience of the European economy.

These dogmatic assertions are coming out of the blue and are purely ideological. No proofs, no rationality, provided.

The European economy being about “adding value”, the author implicitly states that by losing one component of the addition (the input part), only that lost part will be subtracted from the overall result. There is no addition in that game, the so-called added value is actually a margin, therefore a coefficient and a multiplicative factor. If a factor is nullified, the whole equation is wiped-out. Given a quantity of oil and steel, one can build a shiny German SUV (electric of course): you have added value to the steel. But if oil and steel (or other “critical” material) disappears, there is nothing left on which you can add any value, whatever your know-how. If one of the factors is even slightly decreased, the overall result is not “slightly” reduced, it is exponentially scaled down.

Because the winter was mild, and there were stocks and reserves, the European economy could to a certain extent withhold the Russian blow. There were still some inputs stored, or partially replaced, upon which one could “add” value. That won’t last. The “resilience” of the European economy so far relies mostly on a mild winter. But what if the lights are turned off, what if you (in a very short time frame) loose large chunks of materials and energy?

Yesterday there were comments regarding the impact of volcanic eruptions in history (starvations, wars, political revolutions) or even today (possibly this unusually mild winter). These eruptions have huge consequences, in large part due to the sun lighting being (even slightly) reduced (the energy is lost or reduced). One of the commenter noted that there are no more such active volcanos in the northern hemisphere (beside Kamchatka) which could have such impacts. I will argue that the Ukraine disaster will have the same effect: this is our volcano eruption in the northern hemisphere. The (even slight) reduction in light or heat input, conveys a multiplicative destructive power over a whole continent. The effects, here in Europa at least, could pretty much span over the rest of this century.

TINA: There is no alternative to Russian energy which could preserve our life style. Some politician will have, sooner or later, to go to Canossa on Moscow and beg on his knees whoever is ruling at that time. I don’t care about them being humiliated: they are quite used at begging after all when it comes to line up their pockets.

Praising the vassals for displaying resilience when obeying the master does not erase their humiliation. The idea of an independent Europe as a rational actor on the world stage is gone, replaced by a timorous pack of fractious states led by craven opportunists,

The article says that ‘At the time of the invasion, the EU was highly exposed to the import of Russian commodities’ but that was not the true relationship. Russia figured that having Europe get so many commodities at a cheap price from them would ensure a peaceful status with Europe. They never thought that the EU would be lunatic enough to try to cut themselves off from all these commodities which would tend to cripple a lot of their industries and make them less competitive on the world market. Even then this whole business about cutting themselves off from Russia is just theater. The EU still gets Russian hydrocarbons but after they go to India first to be converted to Indian oil. Everybody knows but pretends not to notice and they just pay the much higher prices now. The EU hasn’t even stopped importing Russian diamonds. I would classify that as a luxury but the EU permits that trade to go on. Hungary still gets fuel and the like from Russia because for some reason they do not want to destroy their economy. The Hungarians are strange like that. And the EU certainly hasn’t stopped getting titanium from Russia because that is so vital to some industries like aerospace. I would go so far as to say that yes, the EU is decoupling from Russia – but only stuff that is of importance for the little people. If it effects the elites, then they will still import Russian commodities, even if they have to disguise that fact.

Funny how ease of trade was supposedly the key for avoiding WW3 back when the EEC was formed. But now all of a sudden it is deeply scary when it involves those Ruskies.

Can we trust a Belgian writing for an EU ‘think tank’?

Second largest importer of Russian gas (behind China) is, the EU. Lot of people still buying third party Russian gas also. Are any of these figures even legit. I don’t doubt that it is happening, just the speed of it and bold statements coming from, well, European think tanks. Russia isnt losing a penny, in fact its making more due to high prices, I would expect that to fall as times goes by.

According to the IMF, the Russian economy this year will grow faster than Germany or the UK. It will grow faster next year than in the US, Japan, Italy and much of the rest of the West. GDP per capita growth will exceed the growth of developed countries as a whole. The unemployment rate in Russia, at 3.5%, is the lowest since the fall of the Soviet Union. Europe isn’t looking too healthy by comparison.

making more due to high prices, I would expect that to fall as times goes by.

I don’t think oil in the 70-80 range constitutes high oil prices so you’ve understated russias strength going forward. When I look at pictures of putin in foreign capitals he looks positively gleeful…

Does it matter if EU companies have not left or have a buy-back clause with the Russians that took over the business for the sunny day when the Russia sanctions are over?

https://www.brusselstimes.com/355422/only-8-5-of-western-companies-have-left-russia

The “modern-era” sanctions (there were other sanctions in the ninetees and probably before, Russia is the most sanctioned country on earth by far) started in 2015 (Crimea) and took a surge in 2022. They will not disappear overnight, even if the war ends tomorrow.

A well known buy-back clause: In January 2019, Renault-Nissan (I will stay with Renault for concision) took full control of the (giant) AvtoVaz factory near Moscow through Alliance Rostec B.V., where Renault used to hold 67.61% of the shares and the state-owned Rostec corporation kept the remaining 32.39% of the shares. After the SMO, the arrangement reached is the follows (as I understood it): the local Moscow government takes over 100% of the Renault shares, while Rostec stays unchanged at 32.39%. In exchange Renault gets a buy-back clause, which lasts for 6 years, and which lets them regain their shares, just as before (provided the 6 years time frame). Shortly after that arrangement, the factory, one of the largest in Europe, if not the largest, started to produce a low-cost chinese clone: the factory cannot obviously stay idle for too long. Some additional figures: Russia with 483,000 cars was the second largest world-wide market for Renault, behind France (521,000) but far bigger than Germany (180,000) in third position. This predominent position of Renault in AvtoVaz was built over years, starting in 2008 (that year Renault bought 25% of AvtoVaz shares plus one).

So the buy-back clauses are not forever. Even if Renault comes back (and it probably will, because this factory is really huge), will it be greeted with open arms and a large smile: “Welcome back dude”? I have doubts.

An other point: this AvtoVaz operation (but there are many others of the same kind) was largely made possible because of the neoliberal tide during, and following, the Eltsine days (AvtoVaz being state-owned was intentionnaly deprived of investments just like the NHS is in England today). A lot of people were not happy. These people wanted, and want now, to shrink the part of foreign companies in the Russian economy (a very large part; mind you, a lot of things are run by foreigners in Russia).

Whatever the percentage of foreign companies who have really left (8,5% looks a big number for me, I expected much less), Russia could not have dreamed of a better occasion to kick-out some of these foreigners (and shut up a cohort of noisy neoliberals in the so-called fith column); but also and this may be more useful: to give an edge to their own workers and “entrepreneurs”, avoiding (if possible) the “oligarches everywhere” looming orgy of these Boris Eltsine/Larry Summers happy days.

Wait and see as the British always say. Just now, there is (I think) a sense of “Holy Russia forever and above all” in the population… These foreigners will have a hard time to regain their positions or market shares. Remember these days, not so long ago, where you were unable to look at TV, browse the web or listen to the radio, because of the overwhelming, almost unbearable, thickness of Russian hate, where everybody and his mother had to put a yellow and blue flag in every corner of the screen (nakedcapitalism was pretty much the last island of sanity)? The Russians will remember.

How is it, this author does not recognize “who” instigated divisions between the EU, especially Germany and Russia?

All of this was perpetrated by the US Financial/Military hegemon who purposely placed a wedge between trade imports/exports by Russia and the EU? Thusly, the destruction of Nord Stream.

The US’ “Rules Based Order” demands all the world’s nations remain subservient to its demands, via the use of the US Dollar/IMF/World Bank “Loans.” They have watched China rise from the ashes by becoming a very productive nation. The financial/economic ties between it, Russia and the BRICS is progressing by NOT using the US Dollar while the US System understandably sees the waning of their Dollar Hegemon.

At the same time, that wedge by the US, is causing Western Europe’s nations to reclaim their profitable ties between Russia, China and themselves. We read how Zara and other W. European companies never left Russia despite US dictates. Zara and other big W. European companies continue to make profit from their relations between them and Russia.

“They have watched China rise from the ashes by becoming a very productive nation.”

They have watched with horror as China has refused to be a subservient factory and branch out on their own, after having transferred all their production capacity there to save on wages.

The vast majority of iphones that the PMC so love is made in China, at factories where they had to put up safety nets on the roofs to catch suicide jumpers.

The US sanctions always have a safety valve…That is selective enforcement or cheating. The US bought a shitload of oil after sanctions which didn’t apply to delivery of all earlier deals. Europe hasn’t quite caught on to the spirit of the whole enterprise. Global economies all did better than I would have predicted.

European basic materials industry got nailed, but they were never especially loved. Steel and chemicals … but they detracted from green metrics, so there was already a trend. Developed economies need ‘just so’ compliance, which makes strategic enforcement tricky.

The US couldn’t afford to remove Russian oil from global markets, so it was happy to see India and China buying The most they could ever do was knock a few dollars off the per barrel net price. Sanctions work best when they are used the least, and this will hasten their demise. That is, unilateral US sanctions. They are hardly ‘rules based’ anyway, except in the US.

I guess the benefit of a rules based order is that rules are meant to be bent/broken.