Yves here. This post provides an important insight to the rise in influence of the much-demonized non-corporate right wing: that its success results significantly from voters not changing their beliefs per se, but changing which issues they weigh heavily when selecting parties and candidates. We can see the liberal version of that process here in the US, when the rollback of Roe v Wade led many voters to greatly increase the importance of voting rights in their decision whether and how to vote.

This finding also helps explain why voting patterns tend to shift to the right in the wake of economic crises. Those lower in the social/employment pecking order were already in a more precarious position. If social safety nets don’t provide enough help, they often rely on family or religious group support. It’s also not hard to see that more desperate personal circumstances would lead to resentment of competition from immigrants.

By Oren Danieli, Assistant Professor, School of Economics Tel Aviv University; Noam Gidron, Senior Lecturer Hebrew University of Jerusalem; Shinnosuke Kikuchi; and Ro’ee Levy Senior Lecturer, School of Economics Tel Aviv University. Originally published at VoxEU

Support for populist radical right parties has increased dramatically across Europe. This column looks at drivers of the rise of the populist right between 2005 and 2020and finds that the primary driver in Europe is changing priorities of voters rather than changes in party position or voter attributes. Older, non-unionised, less-educated men are particularly, and increasingly, inclined to prioritise nationalist cultural issues over a party’s economic positions.

Across Europe and beyond, the populist radical right is gaining traction. Populist radical right parties have not only increased their share of the vote – they also join coalitions more often and in some cases lead governments. As discussed in various columns on Vox, this comes with a price: populists in power negatively affect growth and erode stability (Schularick et al. 2022). It is no wonder that a large body of scholarship across the social sciences seeks to identify the drivers of growing support for the populist right (Tabellini 2019, Rooduijn 2019, Cremaschi et al. 2023).

Three narratives regarding the rise of the populist radical right emerge from this body of scholarship. One narrative suggests that changes in parties’ positions – for instance, the convergence of mainstream parties around a similar ideological programme – explain why the populist radical right attracts growing support (e.g. Berman and Kundnani 2021). According to the second narrative, public opinion has shifted in nativist and authoritarian directions – the directions that benefit the populist radical right – following economic shocks and exposure to immigrants (e.g. Hangartner et al. 2019, Ballard-Rosa et al. 2021). Yet a third narrative proposes that public opinion has not changed drastically;¬ instead, it is voters’ priorities that shifted (Bartels 2017, Bonikowski 2017). Based on this hypothesis, votes may change even if voters’ attitudes remain the same. For example, imagine a voter who always opposed immigration but did not much care about the issue. As immigration comes to carry more weight, this voter may gravitate toward the populist radical right even without changing her mind on the topic.

How much of the rise of the populist radical right in Europe does each of these factors – change in party positions, change in voters’ attitudes, and change in voters’ priorities – account for? This is the question we explore in a recent paper (Danieli et al. 2022). We combine information on partisan positions from the Comparative Manifesto Project with data on voters’ attitudes as captured in the Integrated Values Surveys collected from 2005 to 2020. We estimate priorities based on a probabilistic voting model.

We analyse this rich dataset using a decomposition method adopted from labour economics (Fortin et al. 2011). The decomposition approach allows us to gauge how much support for the populist radical right would change when letting only one factor change and holding constant the other factors. This is what we find.

Decomposition Results

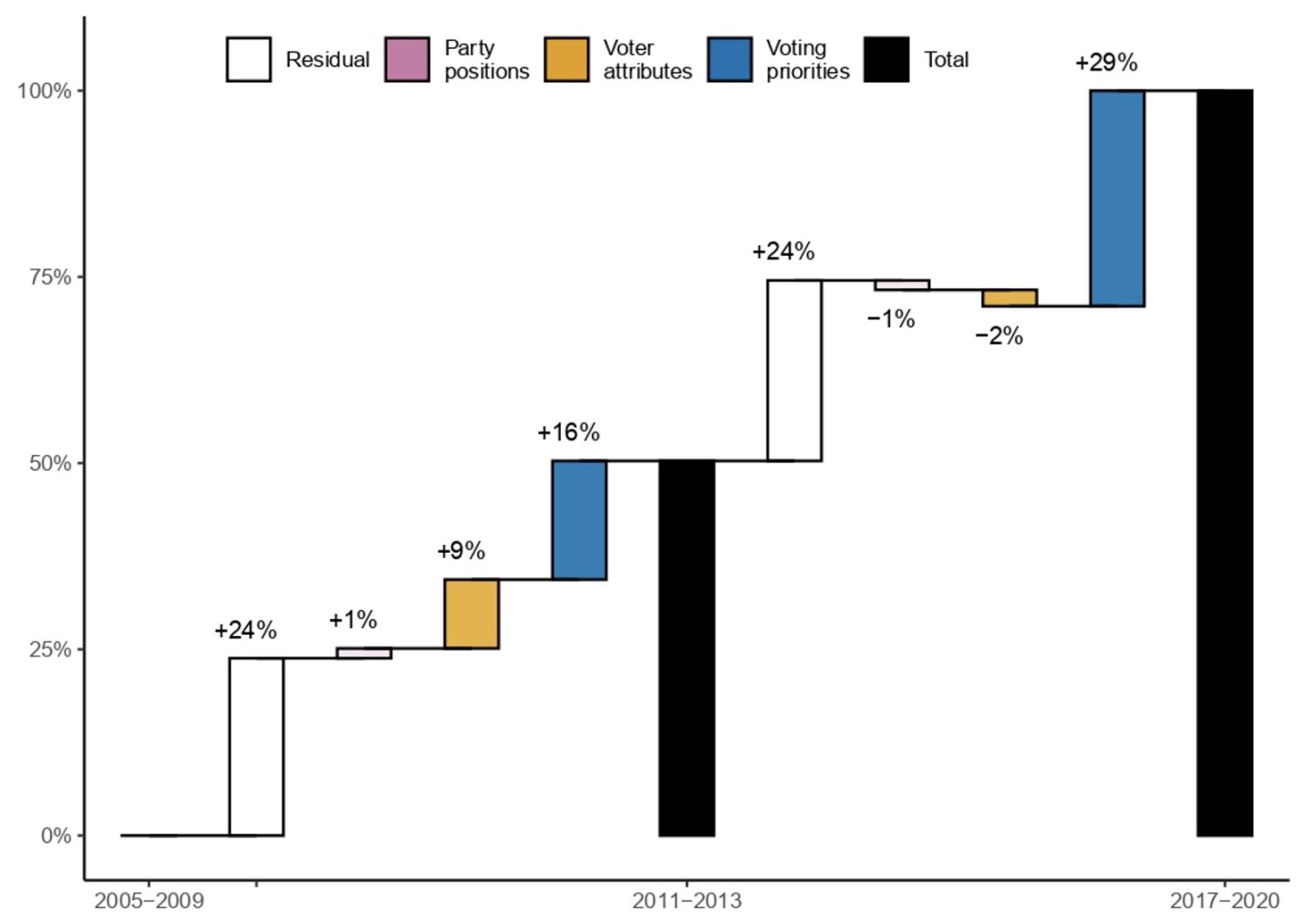

Figure 1 summarises the results of the decomposition analysis. The y-axis shows what percentage of the aggregated rise in support for populist radical right parties is generated by changes in party positions, changes in attitudes, and changes in priorities. We add a residual category for the entry of new parties and for other factors we cannot capture with our data (e.g. the quality of these parties’ leadership). On the x-axis, we divide our data into three time periods based on the years in which the surveys were fielded.

We first observe that changes in party positions explain very little of the changing support for the populist radical right within the time period covered in our data. The action takes place on the side of voters, but not so much in voters’ attitudes as in their priorities.

Figure 1 Decomposition results

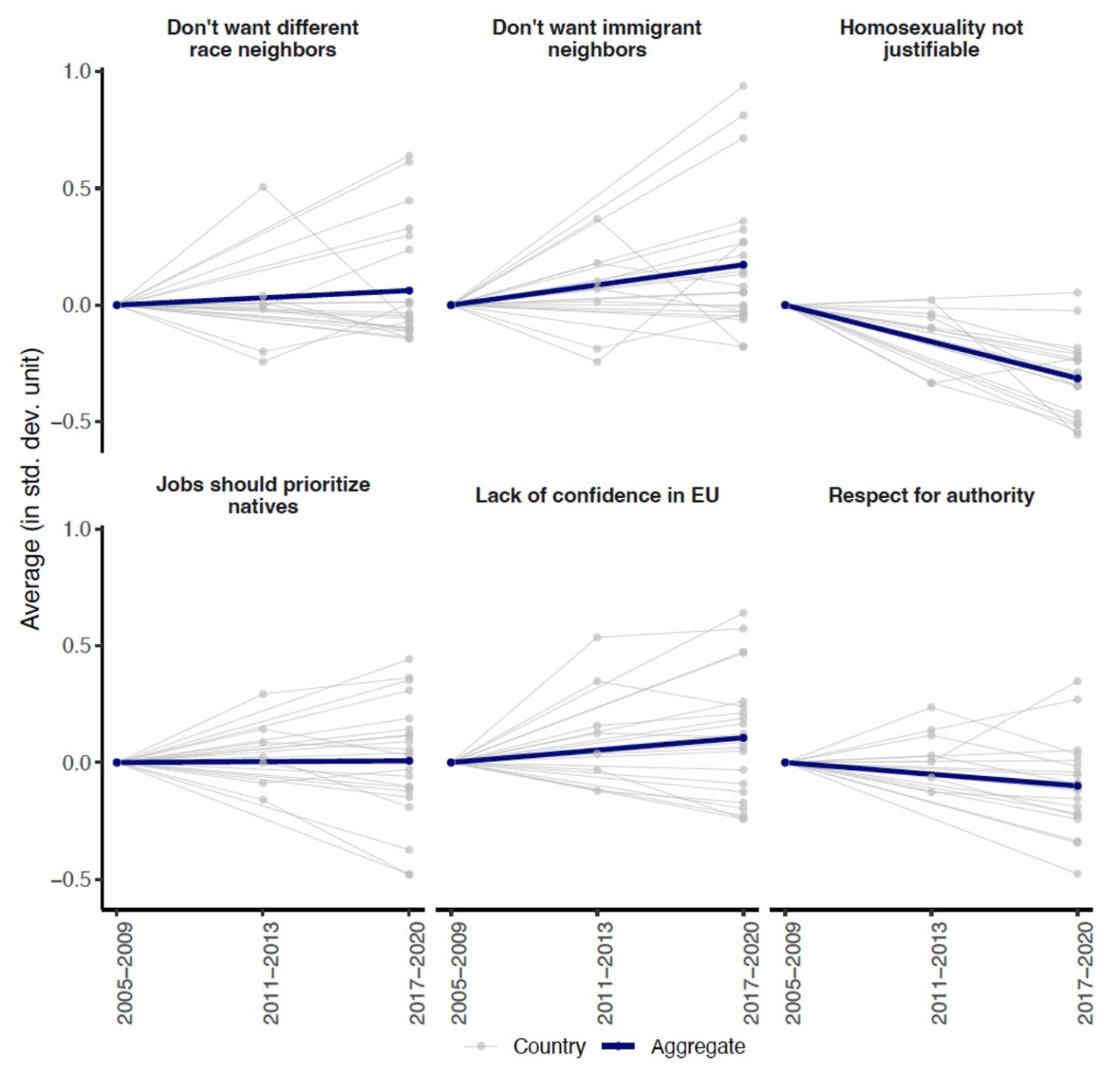

Changes in voters’ attitudes explain only a small share – about 7% – of the rise in support for the populist radical right. This is an important corrective to a common claim in the media that there “has been a slide to the right” in public opinion (Mallet 2022). To further examine this issue, Figure 2 investigates changes in attitudes on cultural issues that often feature in populist radical right campaigns. Higher positive values on the y-axis denote more conservative attitudes. Each grey line represents one country and the blue line represents aggregated public opinion across countries. Clearly, there is no unison conservative turn: if anything, on some issues, public opinion has become more progressive. Scholars, media observers and political operatives should not be quick to accept the claim that public opinion is moving in the direction of the populist radical right.

Figure 2 Change in attitudes

How Priorities Have Changed

While attitudes have not changed dramatically on most issues, what have changed are voters’ priorities. This is by far the strongest result of our decomposition analysis: changes in priorities explain around 45% of the increase in support for the populist right according to our analysis.

To more closely examine which issues gained priority, we distinguish between economic and cultural policy domains. Economic issues deal with the question of ‘who gets what’, while cultural issues are those that more directly pertain to the question of ‘who we are’. While far from perfect, this distinction follows previous research on populism (Margalit 2019).

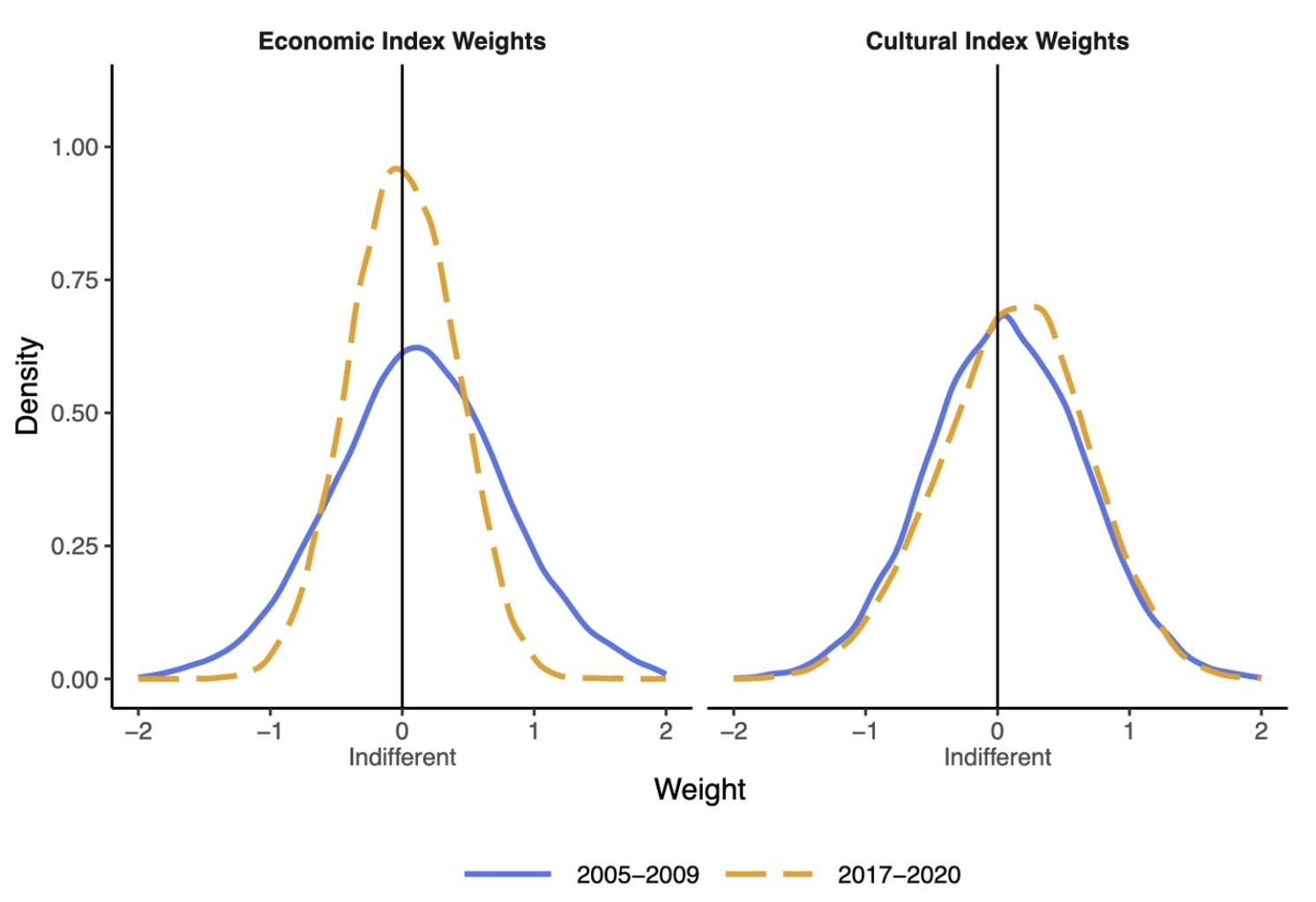

Figure 3 traces changes over time in the estimated weights voters attach to economic and cultural issues. Positive weights imply support for right-wing positions, while negative weights imply support for left-wing positions. The further away voters are from zero on the x-axis, the stronger an issue weighs on their voting decision. For economic issues, we see that over time the distribution of weights has become more narrowly concentrated around zero – that is, more voters are increasingly indifferent to economic policies. In contrast, we see a right-ward turn in the distribution of weights on the cultural dimension. This means that a growing number of voters now put more weight on culturally conservative positions when voting. But who are these people whose vote choice is increasingly shaped by their cultural attitudes?

Figure 3 Change in weights

This change in priorities has not been homogenous across the population. In additional analyses reported in our paper, we find that conservative cultural issues now more strongly shape the voting decisions of men, those without a college degree, those who are not unionised, older individuals, and those who reside in rural areas. It is not surprising that previous analyses have located these groups at the core of the electoral coalition supporting the populist radical right.

Political Change Through Change in Priorities

What does this all boil down to? When we see parties gain support, it is easy to assume that this is because public opinion is moving in their direction. But our work suggests this is not necessarily the case. Electoral upheavals may follow not only a change in attitudes but also a change in priorities, which is what we find in our analysis of support for the populist radical right.

The degree to which our findings travel outside of Europe is an important topic for future research. There is some evidence that in the US, support for Donald Trump should be understood on the background of changing priorities (Sides et al. 2022) and the activation of pre-existing worldviews (Mason et al. 2021). Whether the same applies to non-Western cases of populism – for instance, Brazil – is yet to be explored. While our work focuses on Europe, our decomposition tools could be used in other cases to expand the scope of the comparative conversation on support for the populist radical right.

More broadly, our work underscores the importance of political priorities. We still have limited understanding of how priorities change – and how to theorise and empirically capture those changes. We hope our study guides future research into the drastic shift in priorities over the last couple of decades that we uncover in our work.

See original post for references

Findings are very plausible, I guess, but the data analysis..wowza. Decomposition analysis virgin here.

I’d like to see the same kind of analysis of the left parties and their supporters. 1) Movement in politics is reciprocal. When people move one way, others move (are driven, perhaps) the opposite way. 2) It is my experience (and is, I think backed by research) that people choose their party for whatever reason (history, family, Vietnam), and adapt their policy preferences to the policies of their party, even when they change. Especially I think this is true for new, or emerging issues, ones that people haven’t given much thought to.

I’m going to say that it is a version of the first narrative and that it holds true for many countries and not just Europe. So what happens when the major parties of a country come to an “understanding” and start following policies that benefit the wealthier class but at the same time abandon ordinary people. You have a case of people not leaving their parties but their parties leaving them. After this goes on for a few years and people see that none of the parties are listening to them at all but are chasing ever decreasing marginal issues like left-handed lesbian red-heads, they look around. And it is often found that it is the radical right that are even prepared to listen to them. I saw this in Oz about thirty years ago. And in the US look at 2016 when people gave the middle finger to the establishment and voted for the turd in the burning paper bag. The establishment then uses their power to crack down on the candidates, undermine them, and to also demonize their supporters. So then those people get pushed further along the political spectrum when they see and experience this. If this keeps up we may end up in an age of demagogues.

The other point is that not only have traditional parties acted as if on the same page on economic issues, so there is no choice (coke or diet coke neoliberalism), but in Europe, Orban in Hungary and Peace and Freedom in Poland were to the left of the social democrats on economic issues. Likewise, Le Pen is the one opposing the retirement age changes, not Macron. If you check out candidate Trump, he was to the left economically of the whole GOP field.

I have no idea how that – Rightists seizing economic positions abandoned by the Left – plays out in Europe, but in my experience in the US, the liberal/Left, and especially the TDS-afflicted #McResistance PMC, is impervious to those facts, let alone their implications.

I am not sure about the framing of this article. Older less educated men have developed more culturally conservative priorities, eh? Judged relative to their previous priorities? To the centre? How do we know the young, female graduate population did not shift leftwards? Or the shift in individual male priorities is merely a reaction to the shift in societies’ public stance?

Even if this article is true on its other findings, my suspicion is that public cultural discourse moved sharply left and only cranky old non-PMC men are willing to hold on to their positions, for they gave nothing to lose, and a silent majority keep quiet in fear of the rainbow-shirts….

And in fact, I think the UK political parties have all moved sharply right since 2010 and definitely since 1990, so I am not sure the rest of this analysis would hold in Europe either. Look how the French Socialists and Republicans both imploded in the past twenty years, and the Italian Christian Democrats. Macron’s party has come from nothing, what stability in manifesto position can it have? I don’t see how there is any basis for claiming stability in party views if the parties are not there! I wonder if a party vote/membership weighted analysis of manifestos would show such alleged stability….

A different question is how deep that commitment to the “community” goes.

Far too many times have i seen their like here in Norway pretend as if the very laws they pushed for do not apply to themselves, only those they deem “deplorable”.

Jonathan Hopkin tackles this in his Anti-System Politics: The Crisis of Market Liberalism in Rich Democracies in which he shows how the neuralgia of populations abandoned by technocratic centrist regimes which fail to protect their populations from detrimental market outcomes drives them into the arms of “anti-system” parties of the right OR left — he then goes on to analyze how institutional and cultural circumstances in particular nations favour either the anti-system right or the anti-system left.

https://academic.oup.com/book/33608

This is what’s missing in the analysis above… the US system effectively destroyed it’s left wing from the 70s onwards thru COINTELPRO and other means, so there is no meaningful opposition on the left to receive the disaffected voters. The small left wing parties that do exist do great work, but they are effecively neutered, whereas the right wing populists were easily absorbed/have absorbed and been boosted by the republican party.

Dunno why so many NC readers seem to think that liberals (particularly US liberals) are left when they are center-right. Sanders barely even scratches that center left and he was immensely popular with exactly the white working class types that would have allowed him to beat Trump if he had been the candidate.

This is further exacerbated by the denial on the part of the establishment that their policies have had a negative impact on the working classes. They personally are doing just fine, so when someone complains they look to things such as sexism, racism, anti-immigrant to explain / dismiss the person complaining. In other words if they can find a reason to dismiss the person bringing forward the grievance, they don’t have to acknowledge it. This only makes the problem worse.

The attitude, at least around my parts, have been that the working class has themselves to blame for staying working class. Since the 80s roughly the idea has been that all societal ills can be solved by more education. Thus if you fail to become say a doctor or engineer, it is on you for not making use of the resources put before you.

“Populism” is just a synonym for “democracy”. I know it’s pointless by now to harp on about the abuse of this term, which comes with political consequences, but it bears repeating anyway. They misuse “populism” to mean “demagoguery”—but choose instead to use the term “populism” as an unsubtle way of warning us about the dangers of too much democracy extended to the deplorable masses, rather than the reality that all of this mess is a consequence of too little democracy under neoliberalism. It sucks that the distorted meaning of “populism” has been adopted by people who don’t otherwise agree with the reasons for misusing that word, because it has become the default terminology, but it should be resisted.

In the US the populace is all of us. I know populism has a history, but to me the word always sounds inappropriate when applied to the movement on the right that is in its rhetoric and policies – including “who gets what” and “who we are” explicitly eliminationist and anti-democratic.

Some decades ago Willis Carto appropriated ( maybe misappropriated) the word populist and made it into the synonym for White Power Right which it is regarded as today. For awhile I got the Willis Carto-inspired newspaper The Spotlight-America’s Populist Newspaper just for the fun of it.) I will offer a link on Willis Carto and then a link on his Populist Party.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Willis_Carto

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Populist_Party_(United_States,_1984)

It would take millions of hours of Teach-In type work to enable millions of people to realize that there was a pre-racial/ maybe non-racial Populist Movement decades before the one we have come to know.

Given the study’s conclusions perhaps “populist” and “radical right” shouldn’t be joined at the hip. For that matter is “right” now to always be considered “radical”? Back in the age of High Broderism both committed conservatives and social liberals were considered a bit outre with the ideal Goldilocks position being somewhere in the middle. This conformed with the then mainstream view that politics was about compromise and getting things done. It also allowed big cheese reporters at the NYT and WaPo to pretend to be neutral and not taking sides.

France is a mess and it seems to be all about fear of the “radical right” and how that is being used by the radical Neoliberal. Same here?

pretty much lost me by here,

“Across Europe and beyond, the populist radical right is gaining traction. Populist radical right parties have not only increased their share of the vote – they also join coalitions more often and in some cases lead governments. As discussed in various columns on Vox, this comes with a price: populists in power negatively affect growth and erode stability (Schularick et al. 2022). It is no wonder that a large body of scholarship across the social sciences seeks to identify the drivers of growing support for the populist right (Tabellini 2019, Rooduijn 2019, Cremaschi et al. 2023)”

growth and stability for whom? surely not for the average worker. only shortly for a few rich parasites, who in the end will succumb to their own disastrous polices.

the authors only lightly touch on the free trade/free market polices that are the true drivers of populism, and instead try to paint the new populists as racists homophopes.

i remember when bill clinton said nafta would cut down on illegal immigration, i predicted the exact opposite, we would be deluged with desperate hungry people just trying to survive as free trade ate mexico alive.

i was right.

My memory is that the ClintoNAFTA plan was to destroy society and economy throughout Mexico in order to get tens of millions of Mexican peasants thrown off the land. The plan was also to build a miles-deep belt of maquiladoras along the border from Tijuana to Matamoros to absorb all the Mexican peasants thrown off their land. The maquiladoras would house all the industry to be expelled from America and rebuilt in the new emerging Maquiladorastan along the border.

But when Clinton conspired to get China into the WTO and give it MFN status, most of the American industry went to China instead of to Maquiladorastan, so most of the economic exiles from Mexico kept on moving right into America, because there were far too few maquiladora factories to absorb them all.

So Clinton might have believed what he was saying at the time, though given his bad and deceitful character, he might not have believed it even then.

“populists in power negatively affect growth and erode stability”

We’re used to economists getting their causality backwards, if only because they think “growth” their kind of “growth” is benign.

I have questions.

The underlying assumption here is that the public is informed in a meaningful way and has the opportunity to choose from a wide array of public policy choices, via some form of democratic process. (political terms need to be defined, to be clear). Do these conditions exist in ( insert country here) ?

How do election results reflect public policy preference?

How does ever increasing accumulation, concentration and consolidation of financial resources affect electoral politics?

In general: Does western Liberal Democracy offer any real mechanism for the majority of the public to affect policy formation and outcomes? (In the USA, the answer is mostly no)

We see recently and on this May Day, massive civil disobedience in France. The Macron govt. has acted in flagrant opposition to a vast majority of public opinion. In a so-called liberal democracy, how can the policy preferences of the public be so flagrantly ignored?

I forgot to add the big one:

How does the increasing concentration and consolidation of financial/economic resources affect electoral politics/electoral outcomes?

Is money the same as free speech?

The Supreme Court says it is. The Supreme Court supports rich people buying up all the best speechfront property.

OP makes sense, but mostly because my understanding of Propaganda is that it works more by focusing people’s attention than by “changing their minds”.

In USA at least, Right-wing propaganda has been well funded and well coordinated, hammering away for decades (at least since Reagan, likely since the Powell Memo). With the collapse/destruction of Unions and all “organized” Socialist organizations, the “Left” has no coherent voice. In recent years, the Center (mainstream Democrats = PMC) has begun to respond to the GOP/FOX noise machine, but they’re too squeamish to do it well.

Also, the limited time-frame of the study kinda suppresses any effect of the first competing hypothesis (Party change), in the US at least. The Democratic Party largely gave up on New Deal economic policies in the 1990’s (in exchange for a few $B in campaign contributions), focusing instead on personal identity politics – and has stuck with that [doomed] strategy since then. The GOP went full wingnut around the same time (see: Gingrich). The only major Party policy change since then has been in Foreign Policy (Neocon takeover of Dems), but Americans don’t care about Foreign Policy until we get bombed.

Bernie Sanders has tried to challenge this – as did Corbin in the UK – but they were beaten back. When the “Left” won’t try to focus people’s minds on economic issues, Culture War becomes the field of play, and the Right is much better at using those issues for electoral politics. Ironically, the “left” generally “wins” most of the Culture War “battles” (Gay Rights, etc), but that actually *helps* the GOP Donors maintain control over the aspects of Government that they really care about: Taxation and Regulation.

(Note: the statistics in this piece seem somewhere on a spectrum between opaque and farcical, but maybe (1) my Stats chops are way outta date and/or (2) this summary doesn’t have room for the Math).

“changing minds” is hard. First you assess your base, analyze what drives like-minded voters your way. Set those results aside and then look to see who’s undecided. They’re your primary target. It’s much easier to influence a mind that hasn’t taken a position.

You analyze the undecideds at length, figure out how many actual subgroups you’re working with. Can they be separately targeted? Are there any memes that would 1) undermine opposing thought, 2) build support for your approach, 3) create a sense of importance to your cause and urgency to its adoption. And all of this is done in ways that won’t upset your base (yes, you use all the notes you’ve taken all the time). Always ask yourself: do these suburban votes add to our total or do they subtract from our base?

As for those who oppose you? Undermine them as best you can. Strategies include suppressing their social media, smearing them in the news media, using govt/law enforcement to create appropriate distractions (if the libz riot, help with the arson part : )

I’ve never really tried to change anyone’s mind. Voters who are aware enough to specifically disagree with you are a waste of time. With them you discuss the importance of withholding your vote, not participating, maybe taking a vacation in Mexico that week….

Many good comments as to why the study reveals what it does. I think all these results speak to extremely misguided liberal reforms and talking points.

I’m sticking with “Dip State.” At one time it may have been deep, it has always been blobbish, but in its exercise of power and choice of battles, it has been…peculiar. If using a dating app, I think our leaders would go with words like quirky, adventurous, playful, loyal, obedient and yes, they would also make good pets.

I’d love to know who’s running our world because to them I think we’re all a claymation flea circus. [© Mark Twain]

Is the world moving right? Well, for me it depends on the “other.” If some new bully boys finger the ultra-rich as the problem and see only wealth and not other markers…well, I’m thinking. I’m thinking I might actually get up and vote again. Not because I’m rightwing, but because there is only one enemy and anyone who sees that enemy (the rich) as I do is my friend. At least until the last rich person has been eaten.