Yves here. Readers had fun yesterday shellacking an article that argued that war spending, in particular on the Ukraine misadventure, was good for growth. The piece today questions a recent raft of articles pushing for minimum wage increases to improve overall health levels.

The argument that keeping people even poorer than they need to be is not a negative for health is so wildly nonsensical as to require pretty strong proof. Why for instance does the US find it necessary to fund so many lunches for school age children if even low income parents were earning a living wage?

Similarly, Winston Churchill was very proud of his time as Home Secretary in the mid 1920s. In World War I, it was possible to easily see class differences via height. Churchill took steps to improve the incomes and diets of the lower orders. By World War II, soldiers from upper and lower class backgrounds could not be told apart by their stature.

Now there may be ways that raising minimum wages could fail to improve health much. One is if the minimum wage level is still so low that it does not put workers, particularly working parents, at an income level where they can afford basics: decent food, shelter, utilities, health care, transport. Those costs are all so high in the US that many workers need a big pay rise to get their head above water. Second is that a too-low minimum wage won’t do much to lower inequality. As we have been pointing out since the inception of this site, high levels of inequality impose a health cost, even on the rich. High levels of inequality are strongly correlated with poor social indicators, like teen births, infant mortality rates, crime levels, educational attainment, suicide and drug addiction.

By David Neumark, Distinguished Professor of Economics University Of California, Irvine. Originally published at VoxEU

A handful of studies have led influential health advocacy organisations to recommend increasing minimum wages to improve health. This column assesses the emerging body of evidence on minimum-wage effects on health and health-related behaviours to see whether conclusions can be drawn. Raising minimum wage reduces suicides but has mixed effects on overall physical health, a beneficial or no effect on obesity, and an adverse effect on smoking. More rigorous research on minimum wages and health is still needed.

Economic research and policy debate about the minimum wage has focused on economic outcomes, most notably employment and earnings of low-skilled workers and incomes and poverty. Research has established both pros and cons of higher minimum wages: higher wages for some but – according to most research – job loss for others, and unclear benefits for low-income families in general. For this reason, perhaps, minimum wage policy in the US remains at an impasse. Some states (and localities) have opted for much higher minimum wages, while the federal minimum wage of $7.25, which has not increased since 2009, remains binding in 20 states.

In recent years, researchers have turned to the effects on a multitude of other behaviours and outcomes – mostly health-related. Some studies have led to headlines touting the effects of higher minimum wages in reducing suicides, decreasing smoking, increasing birthweights, lowering depression, improving diet, combatting child neglect, and more (e.g. Cherkis 2021, Gardner 2016, National Employment Law Project 2021, Desmond 2019). If a higher minimum wage delivers these kinds of benefits, then perhaps this evidence should weigh more heavily in the policy debate, offsetting the evidence of job loss from higher minimum wages, and instead supporting substantial increases in the minimum wage.

Advocacy for Higher Minimum Wages Based on Health Benefits

Indeed, findings like these have led influential health research and advocacy organisations to recommend minimum wage increases to improve health. The American Public Health Association advocates raising and regularly updating the federal minimum wage: “More than a decade’s worth of research indicates that increasing the minimum wage is an effective means of improving public health across many settings” (American Public Health Association 2016). The statement cites evidence, for example, that higher minimum wages reduce premature deaths among adults. Similarly, the American Medical Association has endorsed increases in federal, state, and local minimum wages, citing studies finding that higher minimum wages reduce low-weight births and neonatal deaths (American Medical Association 2022).

What Does Economics Predict?

The potential for higher minimum wages to improve health is clear, via raising incomes for some workers (and their families), which can increase expenditures of time and money on health-promoting goods and services and reduce financial stress. On the other hand, job loss can reduce income among other workers and their families, with the opposite effects. The American Public Health Association discounts the latter possibility, citing very selectively from research on employment effects to argue that “recent research has shown that minimum wage increases have very little effect….” In contrast, most studies of minimum wages and health acknowledge these offsetting influences (e.g. Andreyeva and Ukert 2018, Horn et al. 2017, Wehby et al. 2020).

Nonetheless, health benefits from income gains for some workers could outweigh adverse health effects for others who lose their jobs, especially given that there are almost certainly more income gainers than job losers. A net gain would be more likely if there was clear evidence that minimum wages raise incomes in lower-income families. However, the evidence on family income is ambiguous, in part because many minimum-wage workers are not in poor or low-income families, and many low-income families have no workers.

In fact, the predictions of the Grossman (1972) model for health are unclear. We face a diverse set of choices about spending and the allocation of time that can affect health, including purchasing healthcare (physical as well as mental), exercise, diet, goods consumption, and more. Even if the positive effects of minimum wages on income predominate job-loss effects, these choices can be affected in varying ways with different implications for health, depending on the income elasticity of demand for health-related expenditures of money (and time), and the substitutability of health-related goods and activities with time allocated to the labour market (which can be influenced by minimum wages).

Conclusions about how minimum wages impact health and related behaviours or outcomes require careful weighing of the evidence. It also requires recognition that the effects may vary for different behaviours or outcomes because of variation in the sensitivity of health-related expenditures and activities to income and time allocation. Additionally, there is heterogeneity in this sensitivity for workers differentially affected by higher minimum wages.

Assessing the Evidence

Given these considerations, it is perhaps not surprising that the evidence on the effects of minimum wages on health and related behaviours or outcomes is more nuanced than the American Public Health Association and American Medical Association statements indicate. Many studies in this recent literature fail to find beneficial health (or related) effects, and some find negative effects. In addition, some studies find effects that might seem surprisingly large or unexpected – like 8,000 fewer suicides nationally from a $1 increase in the minimum wage (Gertner et al. 2019) or reduced heart disease deaths for 35–64 year-olds (Van Dyke et al. 2018).

This raises the possibility that researchers, as well as policy advocates, are sometimes drawing conclusions that are driven more by spurious changes in minimum wages and in health or related behaviours than by causal effects of changes in minimum wage.

In a recent working paper (Neumark 2023), I assess this emerging body of evidence on minimum-wage effects on health and health-related behaviours, including some dimensions of ‘risky’ behaviour. In addition to assessing the individual studies, I try to determine the conclusions we can draw from studies that use more convincing research designs.

The research I survey covers nine categories of health and related behaviours:

- adult and teen health

- infant and child health

- diet and obesity

- mental health

- suicide (a specific subset of mental health)

- family structure and children

- risky behaviour

- crime

- mechanisms that can affect health (like health insurance).

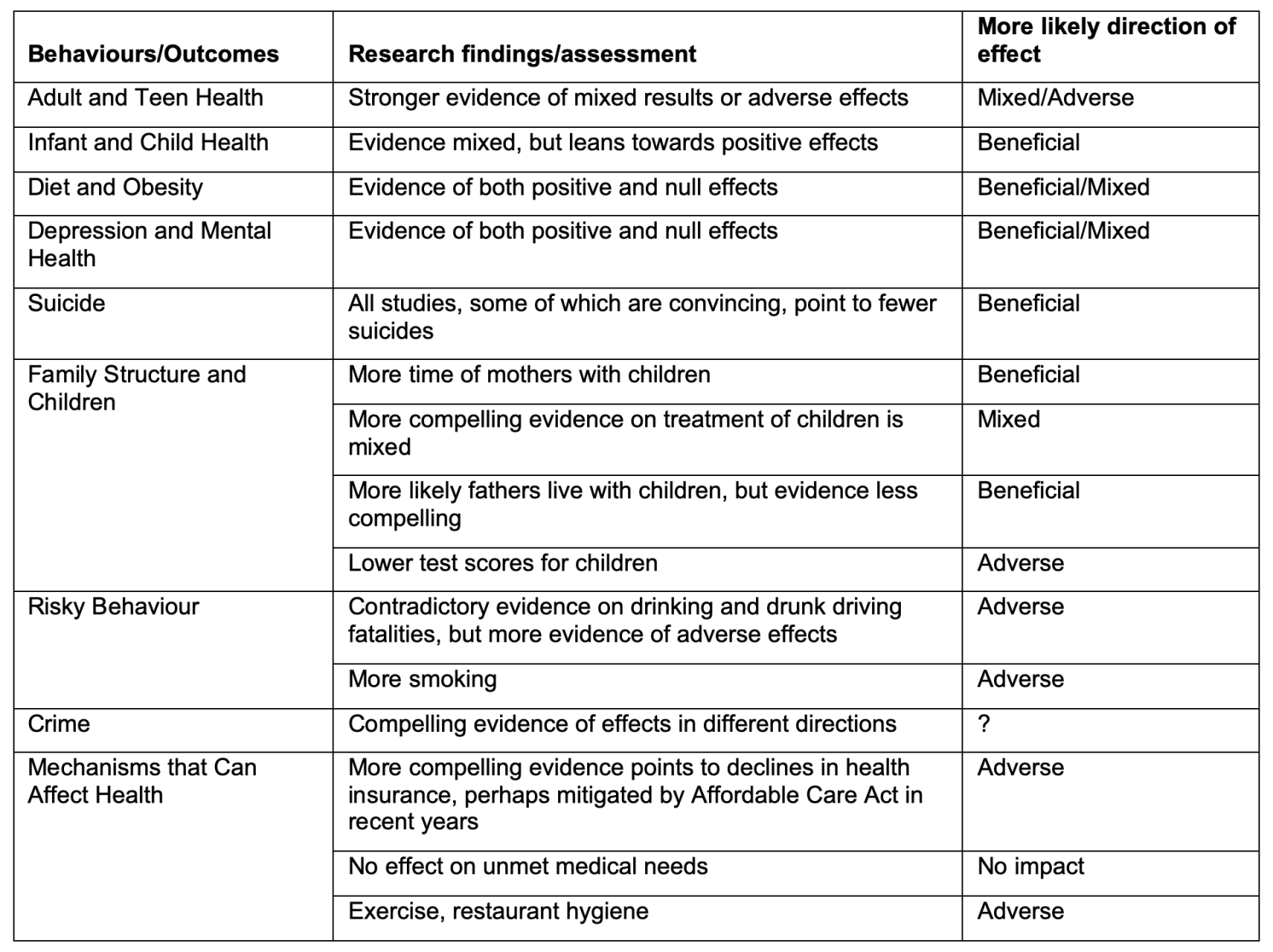

Looking across these categories of health behaviours or outcomes, it is not possible to draw conclusions that point unambiguously in one direction or the other, although within these categories one can more readily draw some conclusions. The evidence across the 63 papers covered in the survey is summarised briefly in Table 1. Detailed tables in the working paper discuss each study, organised by these nine dimensions of health.

Table 1 Summary table on minimum wage effects

The evidence on overall physical health is clearly mixed (e.g. Lebihan 2022, Averett et al. 2018, Buszkiewicz et al. 2021), although a number of the studies claiming beneficial effects are less convincing. This ambiguity may reflect the conflicting evidence on factors that can affect health in some of the other analyses I consider. The findings on minimum-wage effects on diet and obesity either point to beneficial effects (Palazzolo and Pattabhiramaiah 2021) or null effects (e.g. Chapman et al. 2021), but not negative effects. Other evidence indicates that higher minimum wages increase smoking (Huang et al. 2021) and reduce exercise (Lenhart 2019) and possibly hygiene (Chakrabarti et al. 2021).

The evidence for mental health is ambiguous. There are somewhat more studies finding no impact (e.g. Kronenberg et al. 2017) than finding a positive impact (Bai and Veall 2023); none find a negative impact. And, perhaps surprisingly, the evidence for suicide points only to beneficial effects of higher minimum wages (e.g. Dow et al. 2020).

Moving further away from traditional health behaviours and outcomes, studies on family structure and children point in different directions, with evidence that mothers spend more time with children (Gearhart et al. forthcoming), no clear indication of changes in treatment of children (Ash et al. forthcoming), but declines in children’s test scores (Regmi 2020). The evidence generally points to minimum wages increasing risky behaviour – mainly drinking and smoking (e.g. Hoke and Cotti 2016). Evidence on the effects of minimum wages on crime is mixed (e.g. Agan and Makowsky forthcoming, versus Fone et al. 2023).

The best evidence on employer-provided health insurance is more adverse (e.g. Marks 2011), although Medicaid expansions under the Affordable Care Act may have mitigated this influence, and there is no clear evidence of greater unmet medical needs when minimum wages increase (Sabia and Nielsen 2015). And as noted above, other evidence suggests that higher minimum wages may affect health adversely via different channels.

Conclusions

Overall, the mixed conclusions on how minimum wages affect health and related behaviours undermine the evidence base for concluding that “the minimum wage is an effective means of improving public health across many settings” (American Public Health Association 2016).

This survey also points to lessons for research. Many studies of the effects of minimum wages on health and related behaviours fall well short of the rigour that characterises more recent research in labour economics on the employment effects of minimum wages. It seems likely that more rigorous types of evaluations will come to the research on minimum wages and health – and indeed there are already examples, like the work of Dow et al. (2020) on suicides. Whether this leads to less ambiguous conclusions or just reinforces the potentially conflicting effects predicted by theoretical modelling of how minimum wages can affect health remains to be seen.

See original post for references

one data point:

Economic cutbacks making British kids shorter – study

https://www.azerbaycan24.com/en/economic-cutbacks-making-british-kids-shorter-study/

I guess that’s one way to ‘shrink’ those in need.

From the original post on NC:

“The evidence generally points to minimum wages increasing risky behaviour – mainly drinking and smoking …”

Well, there ya go. The poors and working classes have to be kept poor…for their own good. Ya just can’t trust people below a certain income level to have common sense, to think for them selves, or do the right thing. (This is the ugliest sort of paternalistic and selfish thinking by the PMC classes, who probably couldn’t survive a month living in the same financial straights they think are good and morally uplifting for the struggling classes. Social Darwinism: it’s not just for the history books anymore.)

adding, and then I’ll stop:

What good is living in a first world country if your govt and its oligarchic, monopolistic owners are stealing from you every which way.

I mean, that’s naked Protestant theology right there, which is exactly what “economics” is.

I really do believe the “lower orders” would be well served by pillaging the private lives and effects of these apparats and destroying their ability to participate in social production by destroying every piece of data they own. Ruling classes do it all the time.

It ain’t the Protestant theology I was raised with. It’s oligarchic self-justification wearing “religious” drag. / ;)

Funny story. As a kid I was a member of a temperance society’s youth club, not because of temperance, but because it was a very left-wing society.

The history of the society went something like this: in the late 19th century well off people started it for the working class in the honest belief that people lived in poverty because of alcohol abuse and temperance was the means of getting rid of poverty. Didn’t take long for the working class take over the society claiming that poverty was the main cause of drinking, and getting rid of poverty would also solve the alcohol abuse. The very idea was repulsive enough to the original founders to make them leave the society.

Is this the same Winston Churchill that then went on to starve millions of Indians?

Yes. His concern was preserving the Empire, so more robust soldiers good, rebellious Indians bad.

Your comment exhibits halo effect fallacy, which is seeing people as all good or all bad. That is why pretty people are seen as smarter than they are, for instance.

Perhaps, but the question could also suggest both. A complex, contradictory character, Churchill on the one hand: was a rabid elitist, racist and imperialist. On the other: he was a brilliant politician, statesman and “saved” the UK from invasion and total defeat by a hostile power. Of course, these are two polar extremes, just to illustrate. But he was both and, instead of either or. I agree that we should avoid Manichean or halo-effect simplifications.

I would disagree, while he was far more complex, nevertheless he was a johnsonian character.

He owed his status to roosevelt and stalin, and of course adolf.

“For my part, I consider that it will be found much better by all Parties to leave the past to history, especially as I propose to write that history”

What is memorable was that the great british public,after the war was won by others,said thanks for your service, but FU, we do not want to come home to the pre war nightmare.

We can quibble over the fine points: But one thing is for sure, we don’t have the “halo effect” for Churchill – we can call him many things, except handsome ;-)

That’s also the problem with these types of studies where they are looking for a binary answer.

Perhaps they should be looking for the knee of minimum wages relative to local COLA values where increases in minimum wages have minimal improved health outcomes.

It’s like those happiness studies that find out more money makes you happier up until your basic needs are met. Well, how much is that in San Diego California in June 2023?

The federal government should impose a minimum wage that is factored by the local COLA values they already compute and use to determine wages for civilians working for the military. Otherwise the states have a point to say that there should be no federal minimum wage that doesn’t account for cost of living and cost of doing business locally.

Considering the increased cost of food and housing, I am not sure how long the workers had to indulge in drink and smokes. And we shouldn’t forget that minimum wage workers were disproportionately exposed to and hit by Covid.

It was hand waved, but I would think that more than a few of those workers moved from being Medicaid eligible to largely dependent on employer health care. Even with expanded Medicaid the levels were not that great. I knew someone whose main job was around $15 an hour before that was minimum in NY. They had to be very careful about overtime and extra work. I knew them to take most of a month off a year more than once because they were too close to going over. It made eating tricky. (They had health issues that would bankrupt them unless they were far wealthier or had a platinum employer plan.) And NY expanded and were supposedly all about health support.

This is really not sound reasoning. Higher wage earners can also drink and smoke and use drugs. In fact, excess drug and alcohol use is very rampant among some high wage groups. So saying that this might lead to more such use when low wage earners get a little more money is a vacuous argument. If you want better health among your citizens in the US you need to 1) increase wages, 2) implement Medicare for All, 3) increase health courses in grade school through high school, and 4) improve the food supply by limiting how many harmful chemicals and other unhealthy ingredients are in manufactured foods. You could also reduce air pollution (indoor and out) and improve the drinking water supply. You can’t just do one thing and expect the problem to go away.

Another very important variable here is what percentage of the population receives adequate health care?

In developed countries (and many developing countries), even low income people receive adequate health care (not insurance but actual care).

We could increase minimum wage (which is clear) but if folks STILL can’t afford the premiums, deductibles, copays, fees and other health extortion costs, it will not affect health outcomes very much.

Being able to eat healthy food is another one discussed: BigAg and BigFood flood the market with cheap, subsidized GMO garbage food, chock full of HFCS, sugars and toxic ingredients. A big change in Ag and food policies would affect this as well

No amount of conceivable minimum wage increase would provide for fair levels of health care (as opposed to mirages of access to health care. We have to leave that to single payer to address.

With the entire society, aside from the very wealthy, being affected by the general decay of everything including manufacturing, retail, healthcare, and government, then adding the rising costs of everything especially housing, I have two questions: just how high are they proposing the minimum wage to be and are they including the general decay in their analysis?

1968 had the minimum wage ($1.60) with the highest purchasing power. Adjusted for inflation that is $14.27 today. I do wonder just how accurate that inflation count is because a person could afford housing in 1968 using the minimum wage, but they cannot today. I doubt it was good housing, but it was housing, not a tent on a sidewalk or your jalopy.

If one adds the increase in productivity, which was added to wages until 1979 when any increases has gone to the upper, wealthy classes or corporations, after adjusting the the minimum wage using the stated inflation to today, it would be $52.80 per hour.

Before anyone freaks out on that rate, it used to be back in the halcyon days of the 1960s, one was supposed to spend either one-quarter or one-third of one’s take-home pay. Assuming that I did the math right, at 40 hours a week and at a total tax rate of 25%, the net pay would be $6,336 and with a very “cheap” junior one bedroom apart being $2,000 in the San Francisco Bay Area, that would be 32% of ones net pay for housing.

There are states in America that have a tipped minimum wage, which is a low as 0.75¢ in Hawaii to as high as $10.00, plus tips, when combined are supposed to equal at least $7.25 or higher in all states except Colorado, which is $5.12. I hi-lighted the word “supposed” because both anecdotally and by those few news stories, businesses tend to, um, forget to pay the full difference especially if it is some combination of a cash business, isolated, and in a poor area. It is a captive workforce. There are good people everywhere of course, meaning many employees are not robbed, but there are enough wage thieves to be a real problem.

America, the land where you are free to work hard and die poor.

The positive relationship between income and life expectancy is unambiguous. Rich people live much, much, longer than poor people.

The relevant question is therefore: what is required to allow poor people to live as long as rich people?

If the author knows that rich people live much, much, longer than poor people, and yet still finds little or no impact from raising the minimum wage, then the problem might be the inadequacy of the proposed solution.

If the author doesn’t know this, and by appearances he doesn’t, then maybe there is another field that he would be better suited to work in.

https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2016/04/for-life-expectancy-money-matters/

http://www.equality-of-opportunity.org/health/

Neumark is fooling no one. He is a disingenuous hack in service of his oligarch paymasters.

Excellent points. Also, in some countries the rich/poor gap is much, much smaller than the US. The disparity in average life expectancy only gets worse in the US, yet improves in other “developed” countries. The US has the shortest average life expectancy among all OECD countries. It ranks dead last, despite spending 17-19% of GDP on “health care” costs.

Involuntary poverty is incredibly stressful, and this stress alone is terrible for one’s health– how does that get overlooked?

The writer was educated to see, think, and write in bafflegab disconnected from the real world.

If it can not be easily quantified with numbers, it is easy to ignore. Don’t forget that today’s field of economics is a stripped version of political economy with self contained models done with equations for actual studies of human interactions and of society.

June 23, 2023 at 2:02 am

The writer was educated to see, think, and write in bafflegab disconnected from the real world.

The exact reason I quit reading!

It seems to me a “minimum wage” in the sense of transferred value is not a real thing, but a fictional setting of the money system. Since the rich have more power than the poor, indeed, eat the lives of the poor, changing the wage of the poorest simply invites higher classes to raise their own wage; the advance of the first simply leads to a wave of inflation up the food chain. It is a cruel fable hiding the reality of intensified exploitation. Hence the ambiguous or actually negative results noted above in this discussion.