By Lambert Strether of Corrente.

On May 25 of this year, JAMA published Development of a Definition of Postacute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection (“Definition”), an “original investigation” whose authors were drawn from the RECOVER Consortium, an initiative of the National Institutes of Health (NIH)[1]. This was an initially welcome development for Long Covid sufferers and activists, since questions had arisen about what exactly patients were getting for the billion dollars RECOVER was appropriated. From STAT:

The federal government has burned through more than $1 billion to study long Covid, an effort to help the millions of Americans who experience brain fog, fatigue, and other symptoms after recovering from a coronavirus infection.

There’s basically nothing to show for it.

The National Institutes of Health hasn’t signed up a single patient to test any potential treatments — despite a clear mandate from Congress to study them.

Instead, the NIH spent the majority of its money on broader, observational research that won’t directly bring relief to patients. But it still hasn’t published any findings from the patients who joined that study, almost two years after it started.

(The STAT article, NC hot take here on April 20, is worth reading in full.) Perhaps unfairly to NIH — one is tempted to say that the mountain has labored, and brought forth a coprolite — a CERN-level headcount may explain both RECOVER’s glacial pace, and its high cost:

That’s a lot of violin lessons for a lot of little Madisons!

“Definition” falls resoundingly into the research (and not treatment) bucket. In this post, I will first look at the public relations debacle (if debacle it was) that immediately followed its release; then I will look at its problematic methodology, and briefly conclude. (Please note that I feel qualified to speak on public relations and institutional issues; very much less so on research methodology, which actually involves (dread word) statistics. So I hope readers will bear with me and correct where necessary.)

The Public Relations Debacle

Our famously free press instantly framed “Definition” as a checklist of Long Covid (LC) symptoms. Here are the headlines. For the common reader:

12 key symptoms define long Covid, new study shows, bringing treatments closer CNN

Long COVID is defined by these 12 symptoms, new study finds CBS

Scientists Identify 12 Major Symptoms of Long Covid Smithsonian

These 12 symptoms may define long COVID, new study finds PBS News Hour

These Are the 12 Major Symptoms of Long COVID Daily Beast

(We will get to the actual so-called “12[2] Symptoms” when we look at methodology.) And for readers in the health industry:

For the first time, researchers identify 12 symptoms of long covid Chief Healthcare Executive

12 symptoms of long COVID, FDA Paxlovid approval & mpox vaccines with Andrea Garcia, JD, MPH AMA Update

Finally! These 12 symptoms define long COVID, say researchers ALM Benefits Pro

With these last three, we can easily see the CEO handing a copy of their “12 symptoms” article to a doctor, the doctor double-checking that headline against the AMA Update’s headline, and incorporating the NIH-branded 12-point checklist into their case notes going forward, and the medical coders at the insurance company (I love that word, “benefits”) nodding approvingly. At last, the clinicians have a checklist! They know what to do!

We’ll see why the whole notion of a checklist with twelve items is wrong and off-point for what “Definition” was actually, or at least putatively, trying to do, but for now it’s easy to see why the press went down this path (or over this cliff). Here is the press release from NIH that accompanied “Definition”‘s publication in JAMA:

Researchers examined data from 9,764 adults, including 8,646 who had COVID-19 and 1,118 who did not have COVID-19. They assessed more than 30 symptoms across multiple body areas and organs and applied statistical analyses that identified 12 symptoms that most set apart those with and without long COVID: post-exertional malaise, fatigue, brain fog, dizziness, gastrointestinal symptoms, heart palpitations, issues with sexual desire or capacity, loss of smell or taste, thirst, chronic cough, chest pain, and abnormal movements.

They then established a scoring system based on patient-reported symptoms. By assigning points to each of the 12 symptoms, the team gave each patient a score based on symptom combinations. With these scores in hand, researchers identified a meaningful threshold for identifying participants with long COVID. They also found that certain symptoms occurred together and defined four subgroups or “clusters” with a range of impacts on health

So there are 12 symptoms, right? Just like the headline says? Certainly, that’s what a normal reader would take away. And if a temporally pressed reporter goes to the JAMA original and searches on “12”, they find this:

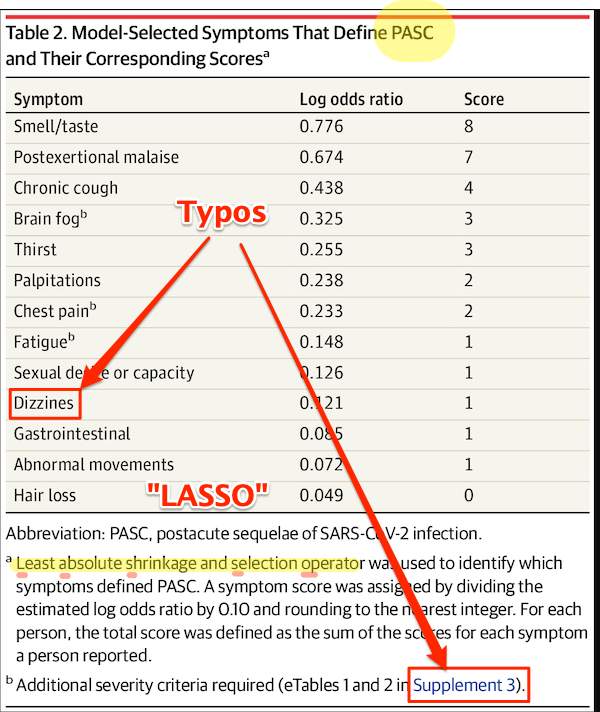

Using the full cohort, LASSO identified 12 symptoms with corresponding scores ranging from 1 to 8 (Table 2). The optimal PASC score threshold used was 12 or greater

And if the reporter goes further and finds Table 2 (we’ll get there when we look at methodology), they will see, yes, 12 symptoms (in rank order identified by something called LASSO).

So it’s easy to see how the headlines were written as they were written, and how the newsroom wrote the stories as they did. The wee problem: The twelve symptoms are not meant to be used clinically, for diagnosis.[3], Lisa McCorkell was the patient representative[4] for the paper, and has this to say:

But the press is not fully understanding the paper which could have dangerous downstream effects. Since the beginning of working on this paper I’ve done everything I could to ensure the model presented in this paper is not used clinically, and I’ll continue to do that. 6/

— Lisa McCorkell (@LisaAMcCorkell) May 27, 2023

Nevertheless, the “12 symptoms” are out of the barn and in the next county, and as a result, you get search results like this:

It’s very easy to imagine a harried ER room nurse hearing “12 Symptoms” on the TV news[5], doublechecking with a Google search, and then making clinical decisions based on a checklist not fit for purpose. Or, for that matter, a doctor.

Now, to be fair to the authors, once one grasps the idea that symptoms, even clusters of symptoms, can exist, and still not be suitable for diagnosis by a clinician, the careful language of “Definition” is clear, starting with the title: “Development of a Definition.” And in the Meaning section of the Abstract:

A framework for identifying PASC cases based on symptoms is a first step to defining PASC as a new condition. These findings require iterative refinement that further incorporates clinical features to arrive at actionable definitions of PASC.

Well and good, but do you see “framework” in the headlines? “Iterative”? “First step”? No? Now, I’d like to exonerate the authors of “Definitions” — “They’re just scientists!” — for that debacle, but I cannot, completely. The authors are well-compensated, sophisticated, and aware professionals; PMC, in fact. I cannot believe that the Cochrane “fools gold” antimask study debacle went unobserved at NIH, especially in the press office. How was it possible that “Definitions” was simply… printed as it was, and no strategic consideration given to shaping the likely coverage?[6] One obvious precautionary measure would have been a preprint, but for reasons unknown to me, NIH did not do that. A second obvious precautionary measure would have been to have the patient representative approve the press release. Ditto. Now let us turn to methodology.

The Problematic Methodology

First, I will look at issues with Table 2, which presents the key twelve-point checklist, and names the algorithm (although without explaining it). After that, I will branch out to a few larger issues. Again I issue a caveat that I’m not a Long Covid maven or a statistics maven, and I hope readers will correct and clarify where needed.

Here is Table 2:

First, some copy editing trifles (highlighted). On “PASC”: As WebMD says: “You might know this as ‘long COVID.’ Experts have coined a new term for it: post-acute sequelae SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC).” Those lovable scamps, always inventing impenetrable jargon! (Bourdieu would chuckle at this.) On “Dizzines”: Come on. A serious journal doesn’t let a typo like that slip through (maybe they’re accustomed to fixing the preprints?). On “Supplement 3”: The text is highlighted as a link, but clicking it brings up the image, and doesn’t take you to the Supplement. These small errors are important[7], because they indicate that no editor took more than a cursory look at the most important table in the paper. On “LASSO,” hold that thought.

Second, the Covid Action Network points out that some obvious, and serious, symptoms are missing from the list:

[T]he next attempts at diagnostic criteria should take into account existing literature that shows more specifically defined symptoms for Long Covid, from objective findings. (E.g. PoTS, Vestibular issues, migraine, vs more vague symptoms like “headache” or “dizziness.) [The Long Covid Action Project (LCAP)] noticed that while [Post-Extertional Malaise (PEM)] was used as a specific symptom with a high score to produce PASC-positive results, other suites of symptoms, like those in the neurologic category, could have produced an equal or higher score than PEM if questionnaires had not separated neuro-symptoms into multiple subtypes and reduced their total scores. This alone could have created a more scientifically accurate picture of the Long Covid population.

Third, these symptoms — missing, from the patient perspective; to be iterated from the researcher’s perspective, at least one would hope — are the result of “Definition”‘s methodology:

An understandable approach from scientists trained to zero in on the most clearly provable effects. But given the enormous breadth of COVID sequelae, this approach deemphasizes a ton of enormously impactful symptoms. We need solid measures of underlying organ damage.

— Clean Air Kits – Next-Gen Corsi-Rosenthal Boxes (@cleanairkits) May 26, 2023

Fourth, I would argue focus on the “most clearly provable effects” — as opposed to organ damage — is a result of the “LASSO” algorithm named in Table 2. I did a good deal of searching on LASSO, and discovered that most of the examples I could find, even the “real world” ones, were examples of how to run LASSO programs, as opposed to selecting the LASSO algorithm as opposed to others. So that was discouraging. I believe — reinforcing the caveats, plural, given above — that I literally searched on “LASSO” “child of five” (“Explain it to me like I’m five”) to finally come up with this:

Lasso Regression is an essential variable selection technique for eliminating unnecessary variables from your model.

This method can be highly advantageous when some variables do not contribute any variance (predictability) to the model. Lasso Regression will automatically set their coefficients to zero in situations like this, excluding them from the analysis. For example, let’s say you have a skiing dataset and are building a model to see how fast someone goes down the mountain. This dataset has a variable referencing the user’s ability to make basketball shots. This obviously does not contribute any variance to the model – Lasso Regression will quickly identify this and eliminate these variables.

Since variables are being eliminated with Lasso Regression, the model becomes more interpretable and less complex.

Even more important than the model’s complexity is the shrinking of the subspace of your dataset. Since we eliminate these variables, our dataset shrinks in size (dimensionality). This is insanely advantageous for most machine learning models and has been shown to increase model accuracy in things like linear regression and least squares.

Since LC is said to have over 200 candidates for symptoms, you can see why a scientist trying to get their arms around the problem would be very happy to shrink those candidates to 12. But is that true to the disease?

Because LASSO (caveats, caveats) has one problem. From the same source:

One crucial aspect to consider is that Lasso Regression does not handle multicollinearity well.

Multicollinearity occurs when two or more highly correlated predictor variables make it difficult to determine their individual contributions to the model.

Amplifying:

Lasso can be sensitive to multicollinearity, which is when two or more predictors are highly correlated. In this case, Lasso may select one of the correlated predictors and exclude the other [“set their coefficients to zero”], even if both are important for predicting the target variable.

As Ted Nelson wrote, “Everything is deeply intertwingled” (i.e., multicollinear), and if there’s one thing we know about LC, it’s that it’s a disease of the whole body taken as a system, and not of a single organ:

There are some who seek to downplay Long Covid by saying the list of 200 possible symptoms makes it impossible to accurately diagnose and that it could be encompassing illnesses people might have gone on to develop anyway, but there are sound biological reasons for this condition to affect the body in so many different ways.

Angiotensin-converting enzyme receptor 2 (ACE2) is the socket SARS-CoV-2 plugs into to infect human cells. The virus can use other mechanisms to enter cells=, but ACE2 is the most common method. ACE2 is widely expressed in the human body, with highest levels of expression in small intestine, testis, kidneys, heart, thyroid, and adipose (fat) tissue, but it is found almost everywhere, including the blood, spleen, bone marrow, brain, blood vessels, muscle, lungs, colon, liver, bladder, and adrenal gland

Given how common the ACE2 receptor is, it is unsurprising SARS-CoV-2 can cause a very wide range of symptoms.

In other words, multicollinearity everywhere. Not basketball players vs. skiiers at all.

So is LASSO even the right algorithm to handle entwinglement, like ACE2 receptors in every organ? Are there statistics mavens in the readership who can clarify? With that, I will leave the shaky ground of statistics and Table II, and raise two other issues.

First, it’s clear that the population selected for “Definitions” is unrepresentative of the LC population as a whole:

One important thing to remember is RECOVER study on #LongCOVID likely has a lot of patients with more mild version of Long COVID. To participate you have to go in for multiple voluntary medical appointments. People with severe illness and/or bedbound are less able to participate.

— Myra #KeepMasksInHealthCare (@myrabatchelder) May 28, 2023

If the patients in “Definition” are not so ill, that might also account for Table 2’s missing symptoms.

Second, “Definition”‘s questionnaires should include measures of severity, and don’t:

Yes. PEM Q has challenges—”post-exertional malaise” is jargon & can lead to respondent self-selection. Plus, PEM can be delay onset.

Also: symptom lists should focus on severity. Mild, transient fatigue after an illness is common. Debilitating, persistent fatigue is different. https://t.co/C9jmiCa2xi pic.twitter.com/xJTtWzmqbk

— zeynep tufekci (@zeynep) May 29, 2023

Conclusion

The Long Covid Action Project (materials here) is running a letter writing campaign: “Request for NIH to Retract RECOVER Study Regarding 12 Symptom PASC Score For Long Covid.” As of this writing, “only 3,082 more until our goal of 25,600.” You might consider dropping them a line.

Back to the checklist for one moment. One way to look at the checklist is — we’re talking [drumroll] the PMC here — as a set of complex eligibility requirements, whose function is, as usual, gatekeeping and denial:

what they did is create basically a means test to figure out a dx but for smthg that is still not fully understood. it's premature and rly limited, & this will only further aid ppl already dismissive of lc

— Wendi Muse (@MuseWendi) June 3, 2023

If you score 12, HappyVille! If you score 11, Pain City! And no consideration given to the actual organ damage in your body. And after the last three years following CDC, I find it really, really difficult to give NIH the benefit of the doubt. If one believed that NIH was acting in bad faith, one would see “Definition” as a way to keep the funding gravy train rolling, and the “12 Symptoms” headlines as having the immediate and happy outcome of denying care to the unfit. Stay safe out there, and let’s save some lives!

NOTES

[1] Oddly, the JAMA paper is not yet listed on RECOVER’s publications page.

[2] “12” is such a clickbait-worthy brainworm. “12 Days of Christmas,” “12 apostles,” “12 steps,” “12 months,” “12 signs of the zodiac,” etc. One might wonder where if the number had been “9” or “14” the uptake would have been so instant.

[3] To be fair to the sources, most of them mention this: Not CBS, Chief Health Care Executive, or the Daily Beast, but CNN in paragraph 51, Smithsonian (9), PBS (20), AMA Update (10), and Benefits Pro (17).

[4] There was only one patient representative for the paper:

I wish so much there was more than me. Patient reps have such limited power but it builds as more are included. I tried to get other voices involved even just to review the paper before publication, but that was blocked.

— Lisa McCorkell (@LisaAMcCorkell) May 28, 2023

One seems low, especially given the headcount for the project.

[5] I was not able to find a nursing journal that covered the story.

[6] Unless it was, of course.

[7] Samuel Johnson: “When I take up the end of a web, and find it packthread, I do not expect, by looking further, to find embroidery.”

There are far more than 12 symptoms of long covid, all one has to do is to follow some of the LC pages on twitter of facebook to read about the diverse problems that some people are facing. Skin damage, is just one example.

As you mentioned, no doubt insurance companies will begin denying benefits to those who have a symptoms other than the 12 listed. The grifting will continue until morale improves etc.

My first gripe is that there seems to be no attempt to examine the ME/CFS-like post-covid (and SARS1!) syndrome(s) as even potentially separate from sequelae due to direct injury from infection. I didn’t read closely. Did I miss something?

From very early days the similarities in symptoms have been obvious. And we’re now to the point where “‘Long Covid’ and ‘Chronic Fatigue Syndrome’ are both associated with T-cell dysreguation and indicators of viral persistence.” is a statement of fact, and “These associations may soon serve to characterize these conditions.” is responsible speculation.

In my opinion this is much worse than miscommunication on NIH’s part.

Sure doesn’t resemble PASC, on THIS planet? MASC, POTS, ME-CFS, Sp02 & pulse fluctuation 3yrs after an infection I wouldn’t have given a thought to, if 32K people hadn’t all DIED in my city, in a few months (& ever more are now dying of PASC damage, CDC mischaracterized as pre-existing comorbidity to IGNORE excess mortality, due to government FEEDING us to a lethal frigging virus, to keep us working & SPENDING, UNMASKED, so kleptocrats can upwardly redistribute our labor, equity & exponentially indenture re-re-reinfected workers, as we succumb?

BeliTsari – Now that’s a truly righteous rant.

12 Monkeys ?

In the movie a pandemic was intentionally spread by international air travel. It didn’t help that I got to see La Jetée in high school. …And no, I am not in the insurance business.

I was thinking The Dirty Dozen, similar to foods with the most pesticide residue following harvest. Or…

I note search engines love the the “10 best…” or “worst” style of post. Page 1 is littered with these using all manner of favorite numbers by the authors. Certainly the Top 3 will be distilled quickly.

A book recommendation;

“A Field guide to Lies” by Daniel J Levitin.

“Critical thinking with statistics and the Scientific Method”.

As far as the NIH’s credibility… I started laughing as soon as I wrote that.

When we investigate the etiology of a disease, like Long Covid Disease, we must explore all possible factors. They can be intrinsic, extrinsic or Idiopathic. This is called “taking the history of the patient”. “The history” is the bedrock of the relationship between the physician and patient. There must be trust, openness and complete honesty, which is underpinned by the legal concept, “physician-patient privilege”.

Physician, assume your empathetic bed-side manner. Please gently ask the long covid sufferer, “Have you encountered, Anthony Fauci or his world-wide team of Yes-Humans? Did you let him/them penetrate your body, with their razor sharp penes? Did they ejaculate into you? How many times did they have their way with you? (warning) These memories can be traumatic.

Was this pharma-sex consensual? Or were you coerced (raped) by threats of starvation, homelessness and shunning?

Noting their answers, then proceed to ask about diet, air quality, stress……………

And there you go.

Short answer, no. LASSO is still just linear regression with the same assumptions of independent variables. As for alternatives, methods for handling interactions varies from principled hacks to outright voodoo science. None of this implies skulduggery, but definitely proceed with caution.

Details, for the curious:

LASSO is a neat little form of linear regression, where you apply a penalty on the L1 norm of the model’s parameters. Think: a penalty on the absolute size of the coefficients/betas/whatever terminology you’re comfortable with. The L1 norm is like the Manhattan distance some of us might have learned about, vs. the L2 norm/Euclidean distance. Why might we do this? Well, due to some strange properties of circles (the set of all points 1 unit distance from the origin) under different definitions of distance (i.e. not $c^2 = a^2 + b^2$), the L1 norm induces sparsity in the parameters. That’s where the “setting to zero” part comes in.

Th would correspond to the most “meaningful” variables if you wanted to poke around with a scatter plot. It’s a good “first pass” for a rough-and-ready analysis, but I won’t speculate on why many think LASSO results are publishable in and of themselves.

However, there’s a more than few caveats here:

– there are no guarantees that the variables selected WILL be the most meaningful, or even independent. That viewpoint is merely a heuristic and fails under a wide range of common conditions such as confounders (read: common causes) or scaling issues (read: measurement scales based on scientific understandings, not those optimised for numerical stability).

– the sense in which these findings are meaningful depend on the coding and representation of the variable, and only implies meaningful in the linear, “additive and independent” sense. For our non-mathematical readers, this is kind of like saying you assume you can always double, halve or flip the sign of your variables* and see a corresponding change in the output variable**. To see why this is silly, imagine doubling someone’s height while holding their weight constant, or running the clock back to -10 years of age.

– as identified above, colinearity (or even low condition number) hurts your optimisation process, and thereby your findings.

– the number of nonzero elements is tightly tied to the strength of the penalty, with stronger penalties selecting fewer values. Selection of this penalty is strictly subjective with only heuristics and experience to guide you.

I could go on, but I’m already well into data nerd territory. In summary, the LASSO approach is fine if you’re trying to do routine exploratory analysis, but shouldn’t be passed off as serious scientific work.

To highlight the biggest limitation, I mentioned above the assumption of independence and the failure under confounding variables. These are often necessary assumptions to render solving the equations tractable, but gets swept under the rug when presenting the conclusions. This is more than an issue of naive covariance or numerical stability though. To cite XKCD, correlation doesn’t equal causation, but it does wiggle its eyebrows suggestively while mouthing “look over there”. If variables are covarying, it is often the case that there is a common factor at work in some sense. This is what makes fine-grained modelling and an attempt to get at causal mechanisms so important. The sale of umbrellas doesn’t cause car accidents, the bloody rain does!

Lambert is right to be sending up some warning flares here. We’re searching for our keys under the streetlight, instead of doing the hard work of, you know, understanding the problem. (Or, it must be said, sobering up and laying off the kool-aid.) The fact that thresholding is being applied to such slapdash work is actually making my blood boil a bit.

So far I’ve said the approach isn’t appropriate, but I haven’t proposed a solution. If I were working on this problem, I’d instead be concentrating on modelling the causal process, then see to what extent the various components contribute to observed outcomes. Andrew Gelman has a great blog post about how to think about inference for complicated problems, and has a very knowledgeable commentariat pitching in with their viewpoints. In general I would say if you read a “scientific” paper that’s NOT applying a variant on these methods, you should treat it with some skepticism. For low-level sciences such as physics, this is generally how things are done anyway. Biology makes things much harder, but that just means we need to be more demanding in our standards of evidence if someone’s making grand claims.

There are obvious exceptions where the process is too complex to directly model. I’m looking at you, social sciences. In cases like this, a regression analysis (LASSO or otherwise) is a great way to tame some of the complexity and start to get a sense of what’s going on. However, the flipside of this leniency is that the findings must be likewise limited in their claims.

Attempting to model the actual process doesn’t completely solve the problem (your causal assumptions may be wrong, for example), but it’s a much more principled approach than “throw black box algo at problem and let gradient descent sort it out”. Unfortunately the latter approach is much easier, taking about 2 minutes to set up and run once you know what you’re doing vs. weeks of work in the former. Machine learning has become the new p-hacking, and the damage of the last 30 years of “academic work” is going to take some unfamilyblogging.

* In practice this isn’t always an issue…you can often limit yourself to a subset where relationships are more or less stable (e.g. restricting a study to an age group) and then flag anything outside what you’ve seen as potentially unreliable. If your heights goes nowhere near zero and only applies for those between 150cm and 185cm, for example, you don’t need to worry about flipping the sign or the doubling/halving problem. Independence, or the lack thereof, is still an issue.

** Log odds of the output in this case

The process here that Lambert has summarized reminds me of the process involved in trying to hammer out some kinda specific and mutually agreeable psychological disorders with lists of discreet symptoms. In most cases a clear etiology hasn’t been identified for those either.

Maybe I’m just extra persnickety but my experience has been that learning enough about particular psych disorders has lead me to realize our established diagnoses are more or less all baloney and the entire process of establishing is deeply flawed and obnoxious.

I wanted to add a bit to my theory of this following more or less the process by which psychological disorders are officially defined.

What I’ve seen regarding the publishing of papers sequelae for this sort of thing, is there’s usually a trio of papers.

The first will have a title like “an initial exploration of underlying concepts involved in blah blah blah” and will be a more kind of theoretical/philosophical discussion of whatever is being looked at.

The second will usually have the word “definition” somewhere in the title and will describe the process of constructing a questionnaire for rating symptoms, as this paper seems to do.

The third will usually be some kind of broader application of the questionnaire described in the second paper, and will engage more with problems identified with the questionnaire once it’s been given to a wider population, maybe a comparison of responses from the target population vs general/control population.

Also, in terms of actually codifying the disorder as something diagnosable and, of course, billable, it definitely requires much broader input and agreement beyond the researchers involved in a single study.

As far as our diagnostic system basing itself on a set of discreet symptoms, a perhaps helpful example of how this is deeply flawed it the way personality disorders are diagnosed.

The standard diagnosis for each personality disorder relies on a set of symptoms that is odd numbered (7, 9, 11, etc), and a simple majority is required for an affirmative diagnosis, such that two people can be diagnosed with the same disorder while only having one single symptom in common with one another.

There was a huge collective effort put into getting an alternative diagnostic mechanism for personality disorders codified in the DSM V, which was partially successful in that it was included as an “optional” alternative. Under this optional framework, there are a number of domains of functioning, I think it’s four, iirc, which are like various aspects of individual and interpersonal functioning. Each domain has a discreet number of delineations, which are each rated on a numerical scale for how seriously one’s functioning in the domain is negatively impacted.

So under this framework the idea is to get a broad picture of how well or poorly a person is able to function day to day, as opposed to whether or not the person matches a particular typified disorder, which is the goal under the standard framework.

Imo, fwiw, the optional framework is much more materialist and oriented toward trying to help a person deal with whatever difficulties they themselves identify as causing them difficulty/hardship. It might offer an example of a better approach for similarly codifying long covid, while we’re still lacking a better understanding of the actual etiology, etc.

> If I were working on this problem, I’d instead be concentrating on modelling the causal process

Thank you very much, this is exactly what I was hoping for.

“

Here is a long thread from a study author on how they used LASSO:

Readers, thoughts?

Weighing in again:

“Cutoff at the elbow” is the standard heuristic for these kind of problems – look for where the decrease in the error flattens off, as this says something about the “natural dimensionality” of the problem. In the above chart, this behaviour isn’t exactly present. In cases such as the above, pick a number and defend your choice making reference to external factors. (Typically costs associated with false positives and false negatives.)

To their credit, they are displaying both uncertainty intervals and appear to have some kind of theory about the costs of misclassification, so they’re not complete cow{people of nonspecific gender}. Still, it’s telling that they only discuss false positives and not the false negative case. A good fit for the stereotype of PMC “eligibility criteria”.

I didn’t go into the rest of the thread, but its standard reading of coefficient tables. When you see “LASSO” just imagine they’re doing a standard regression analysis. I can’t see any evidence that they blocked confounding paths or applied “synthetic randomisation” tricks like IPW. Definitely interesting for curiosity’s sake, so long as you keep practiced skepticism and understand most (if not all) of the models assumptions have been violated. If they were on my team, this would be day 1 of an analysis, not the finished report to send to the bosses. Unfortunately, I remember working as a researcher and being pushed to jam out worse stuff than this by my CI. Novel “findings” are more important than being right. Academia is a dumpster fire, like so many of our institutions.

Golly, my blood was already boiling before I read this. It’s nothing but hot air isn’t it?

More sloppiness. And somebody else noticed a typo in Table 2!

I forgot to mention that many, many, many of the RECOVER team members, including the leadership, are from MGH, whose sociopathic Infection Control Department dropped the universal masking requirement, endangering patients (clearly not their first priority).

My husband and I are part of the Recover study. We joined over a year ago. It has been very useful for us to participate in the study because they do extensive testing and each of us has flagged different kinds of tests based on our symptoms and disease progression. Some of the tests might not have been approved by our insurance, or recommended otherwise, and they have helped us identify conditons, organ damage, and markers we need to monitor. In both our cases our Long Covid symptoms have worsened over time. We have several specialists we work with on an ongoing basis.

We are also part of a separate weekly Long Covid suport group that’s been meeting also over a year. Members’ ages range from mid 20-s to late 50s. We all speak about our symptoms and the challenges we face managing this condition and have become quite close. It is very, very tough.

I will say it did surprise me that there was a point system being developed to define Long Covid, and as it’s been stated here, several symptoms and complex conditions are not included in the key symptoms chart. For example, members in our group suffer from dysautonomia, chronic pain, and serious gastrointestinal issues. Psychological issues are prevalent in all of us.

I’m crossing my fingers that with time Long Covid will be defined more precisely and specific treatments will be developed. A lot of people have no idea what it’s like, and how traumatic and debilitating it is. It’s hurtful for us when what we are going through is not taken seriously and we are made to feel it is all in our heads.

I came across this Twitter trail from one of the Recover patient reps with some commentary/critiques/clarification: https://twitter.com/LisaAMcCorkell/status/1662480018847719424?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email

Many thanks to Lambert and all for their contributed expertise. As an I-hope-still-intelligent reader, I needed to look up “PoTS” or “POTS” — an acronym I’d missed. In case others are in the same situation, here’s one link I found on Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome.