By Stefania Albanesi, Research Associate at National Bureau Of Economic Research (NBER), Professor of Economics at University Of Pittsburgh, Antonio Dias da Silva, Principal Economist at European Central Bank, Juan Francisco Jimeno, Adviser, Structural Analysis and Microeconomic Studies Department at Bank Of Spain, Ana Lamo, Principal Economist at European Central Bank, Alena Wabitsch, PhD candidate in Economics at University Of Oxford. Originally published at VoxEU.

Recent advancements in artificial Intelligence have been met with anxiety that this will have large negative impacts on employment. This column examines the link between AI-enabled technologies and employment shares in 16 European countries, finding that occupations potentially more exposed to AI-enabled technologies increased their employment share. This has been particularly the case for occupations with a relatively higher proportion of younger and skilled workers.

Recent advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) have revived the debate about the impact of new technologies on jobs (e.g. Frey and Osborne 2017, Susskind 2020 and Acemoglu 2021). Waves of innovation have usually been accompanied with anxiety about the future of jobs. This apprehension persists, even though the historical record suggests that previous concerns about labour becoming redundant were exaggerated (e.g. Autor 2015, Bessen 2019). This is because the potential negative effects of technology on employment have always been counterbalanced by increases in productivity and creation of new tasks. It remains an open question if the same can be expected from AI-enabled technologies.

Existing Evidence on Artificial Intelligence and Employment

AI breakthroughs have come in many fields. These include advancements in robotics, supervised and unsupervised learning, natural language processing, machine translation, or image recognition, among many other activities that enable automation of human labour in non-routine tasks, both in manufacturing but also services (e.g. medical advice or writing code). Artificial Intelligence is thus a general-purpose technology that could automate work in virtually every occupation. It stands in contrast to other technologies such as computerisation and industrial robotics which enable automation in a limited set of tasks by implementing manually-specified rules.

The existing empirical evidence on the overall effect of AI-enabled technologies on employment and wages is still evolving. For example, both Felten et al. (2019) and Acemoglu et al. (2022) conclude that occupations more exposed to AI experience no visible impact on employment. However, Acemoglu et al. (2022) find that AI-exposed establishments reduced non-AI and overall hiring, implying that AI is substituting human labour in a subset of tasks, while new tasks are created. Moreover, Felten et al. (2019) find that occupations impacted by AI experience a small but positive change in wages. On a different note, Webb (2020) argues that AI-enabled technologies are likely to affect high-skilled workers more, in contrast with software or robots. This literature focused mostly on the United States.

A recent Vox column (Ilzetzki and Jain 2023) discusses survey results from a panel of experts about the potential impact of AI on employment in a number of high-income countries. Most of the panel members believed that AI is unlikely to affect employment rates over the coming decade.

Our Study

In a recent paper (Albanesi et al. 2023), we examine the link between AI-enabled technologies and employment shares in 16 European countries over the period 2011-2019. Our sample period coincides with the rise of deep learning applications such as language processing, image recognition, algorithm-based recommendations, and fraud detection. Those are more limited in scope than the current generative AI models such as ChatGPT. Deep learning applications are however revolutionary and still trigger concerns about their job impacts. We use data at 3-digit occupation level (according to the International Standard Classification of Occupations) from the Eurostat’s Labour Force Survey and two proxies of potential AI-enabled automation, borrowed from the literature. The first proxy is the AI Occupational Impact created by Felten et al. (2018) and Felten et al. (2019), which links advances in specific applications of AI to abilities required for each occupation as described in O*NET. The second one is a measure of the exposure of tasks and occupations to AI, constructed by Webb (2020) by quantifying the text overlap of AI patents descriptions and job description from O*NET.

According to these data, between 23 and 29% of total employment in the European countries was in occupations highly exposed to AI-enabled automation (upper tercile of the exposure measures). These occupations mostly employ high-skilled, high-paid workers, in contrast with other technologies such as software.

Main issue Results

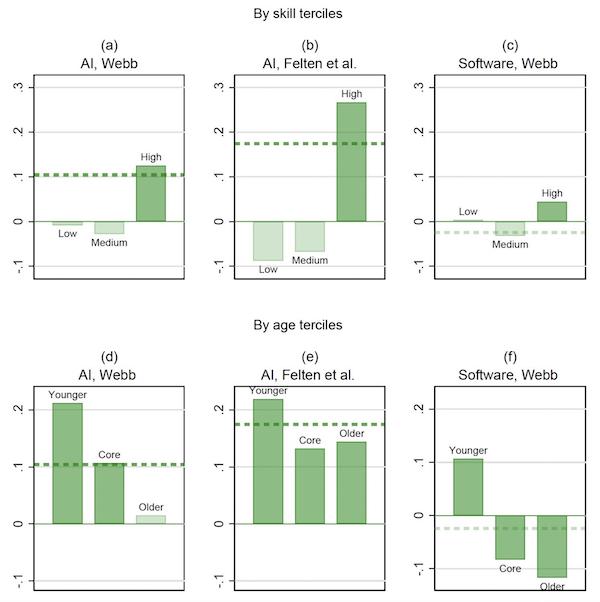

We find a positive association between AI-enabled automation and changes in employment shares in the pooled sample of European countries, regardless of the proxy used for our sample of European countries. According to the AI exposure indicator proposed by Webb (2020), moving 25 centiles up along the distribution of exposure to AI is associated with an increase of sector-occupation employment share of 2.6%, while using the measure provided by Felten et al. (2018, 2019) the estimated increase of sector-occupation employment share is 4.3%. The estimated coefficients are displayed by the dotted line in the left and middle columns of Figure 1.

Figure 1 Exposure to technology and changes in employment shares, by skill and age

Source: Albanesi et al. (2023).

Notes: Regression coefficients measuring the effect of exposure to technology on changes in employment share. Each observation is a ISCO 3 digits occupation times sector cell. Observations are weighted by cells average labour supply. Sector and country dummies included. Sample: 16 European countries, 2011 to 2019. The coefficient for the whole sample is displayed by the horizontal dotted line. The bars display the coefficient estimated for the subsample of cells whose average educational attainment is in the lower, middle, and upper tercile respectively of the education distribution (first row) and of cells whose workers average age is in the lower, middle and upper tercile respectively of workers age distribution (second row). Coefficients that are statistically significant at least at the 10% level are plotted in dark shaded colour.

Technology-enabled automation might also induce changes in the relative shares of employment along the skill distribution and thus impact earnings inequality. The literature on job polarisation shows that medium-skilled workers in routine-intensive jobs were replaced by computerisation (e.g. Autor et al. 2003, Goos et al. 2009). In contrast, it is often argued that AI-enabled automation is more likely to complement or replace jobs in occupations that employ high-skilled labour.

Panels (a) and (b) in Figure 1 display the estimated coefficients of the association between changes in employment and AI-enabled automation by education terciles. Significant coefficients are plotted in dark shaded colour. There is no significant change in employment shares associated to AI exposure for the occupations whose average educational attainment is in the low and medium terciles. However, for the high skill tercile, we find a positive and significant association: moving 25 centiles up along the distribution of exposure to AI is estimated to be associated with an increase of sector-occupation employment share of 3.1% using Webb’s AI exposure indicator, and of 6.7% using the measure by Felten et al. Panels (c) and (d) in Figure 1 report the estimates by age terciles. AI-enabled automation appears to be more favourable for those occupations that employ relatively younger workers. Regardless of the AI indicator used, the magnitude of the coefficient estimated for the younger group doubles that of the rest of the groups.

AI-enabled automation is thus associated with employment increases in Europe, and this is mostly for high skill occupations and younger workers. This is indeed at odds with evidence from previous technology waves, when computerisation decreased relative share of employment of medium-skilled workers resulting in polarisation. We also do not find evidence of this polarisation pattern for our sample when examining the impact software-enabled automation proxied by the software exposure by Webb (2020). Panels (c) and (f) in Figure 1 display the estimated coefficients. The relationship between software exposure and employment changes is null for the pooled sample, and we do not identify evidence of software replacing routine medium skill jobs. Across age groups, core and older workers drive the negative impact of exposure to software on occupations’ employment shares.

Despite the results for employment shares, we did not find statistically significant effects on wages for either AI or software exposure, except for the Felten et al. measure, which indicates that occupations more exposed to AI have slightly worse wage growth.

Our results show heterogeneous patterns across countries. The positive impact of AI-enabled automation on employment holds across countries with only a few exceptions. However, as we discuss in the paper, the magnitude of the estimates varies substantially across countries, possibly reflecting differences in underlying economic factors, such as the pace of technology diffusion and education, but also to the level of product market regulation (competition) and employment protection laws.

Summary

To sum up, during the deep learning boom of the 2010s, occupations potentially more exposed to AI-enabled technologies increased their employment share in Europe. This has been particularly the case for occupations with a relatively higher proportion of younger and skilled workers. For wages, the evidence is less clear and varies between neutral to slightly negative impacts. These results need to be taken with caution. AI-enabled technologies continue to be developed and adopted and most of their impact on employment and wages are yet to be realised.

Authors’ note: The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the ECB, the Banco de España or the Eurosystem.

Though this is interesting, it’s already out of date. It spans 2011-2019, and the world has changed even more in those four years. Most importantly, it doesn’t address Generative AI, simply because the major players, such as Stable Diffusion and ChatGPT weren’t available when this research was conducted. And both of those technologies have evolved significantly in the six (ish) months since their wide release. At the moment, it is largely creative fields that are being impacted–artists, writers, actors–but knowledge workers of all types will be affected. AI Bros touting the rise of the Prompt Jockey are already seeing the technology moving beyond them. So many people will be out of a job, and so few people seem to know or care.

Of course, TPTB (and their lackeys like Adobe’s AI Evangelists) will be waiving this study around as empirical evidence that GenAI is the wave of the future, and those who don’t adapt will perish.

I’d be somewhat skeptical on this article. AI is looking like the .com explosion of hype the late 1990’s. That set of the .com (.bomb) crash. At one point industry had 500,000 job openings and three weeks later there were 350,000 people on the street (laid off). Money was flowing everywhere. A one page business plan could get you a couple million of VC money. I suspect this will happen with AI. I’ve got analysis tools developed for AI systems to detect drift and chances in operating patterns. Simply how to tell if you AI is going rogue or nuts. I’ll wait for the dust to settle before I think about what to do with them. A major problem is that AI usage requires a NONTRIVIAL skill set to get valid consistent results.

Didn’t we see much the same play out more recently with blockchains/crypto?

AI can never get completely valid or consistent results in human terms because it is a black box, and we humans have no idea what logic it is using to get results.

It can perhaps get useful results for some people.

No state is going to allow a truck without a driver and license. I see AI right now as a media, content creator, coding , network administrator but not anything in the real world application. Is it going to be a bartender, a plumber or electrician? Lots of things it’s no where close to being viable. Learning to code was the dumbest idea as that will be the first thing to go with an AI language model. Hence why they call it programming languages.

As in you mean “AI will replace all the software engineers”?

Myself as a specific breed of the above the first reaction is a face-palm, at the “well, no idea what they are talking about”. LLMs are very good at producing text, programming languages included, but the thing about software is that the actual code (the thing AI can generate) is basically the last formal step after many many other steps.

In a sort of reversed way this like saying “AI will replace all the chefs and cooks and restaurants because it can generate dish recipes”.

This comic strip explains this perfectly (no affiliation).

“Our sample period coincides with the rise of deep learning applications such as language processing, image recognition, algorithm-based recommendations, and fraud detection. Those are more limited in scope than the current generative AI models such as ChatGPT. ”

Translation: Our paper uses a clickbait headline to confuse different types of tools to make it seem more relevant to the current, generative AI discussion than it is to current policy discussion. We are very serious people doing very serious work. Please cite us!

My view is AI will sink the professions, the knowledge workers, and have a much smaller effect on the trades.

Or, jobs with tangible requirements will be little effected, and knowledge base work will be greatly effected by AI.

Especially Lawyers, some Medical practices and hope of all hope really decimate politicians.

I couldn’t understand a word of that. However, British Telecom just announced that AI was going to let them fire 55,000 workers by 2030, which is evidence enough of its impact on jobs.

I have the feeling that those companies that replace a lot of workers with AI are going to have a lot of problems including bankruptcy later on.

That will not stop companies from trying to dump their staff.

I doubt the kind of AI they’re so excited about out there has been around long enough to really know what effect it’s going to have other than killing the jobs of low level content creators. Current AI derived content is pretty obviously idiot level, but it will get better. The hype seems to indicate that the target of AI ultimately is to cut out Burnham’s Managerial Class, thus shunting more power and money upward.