By Lambert Strether of Corrente.

I put this article from Kevin Kavanaugh, “Pandemic Strategies Are Inadequate To Assure Public Safety,” in Links yesterday, and in what I will struggle to make a short post, I want to draw out some implications of these paragraphs from that link:

The lack of publicly available data regarding the incidence of MRSA, COVID-19, and other pathogens in the United States is concerning.

Unfortunately, our infectious disease policy appears not to be fixing these problems but instead is retreating. The draft CDC Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC) updated infection control recommendations need to adequately address screening.

One of the worst proposed policies is Enhanced Barrier Precautions (EBP), an antiaptronym [word of the day] since they are watered-down precautions that are even being advocated for Candida auris and MRSA.

So, since I’ve already had a go at HICPAC, I thought I’d look into “Enhanced Barrier Precautions” and MRSA (Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus Aureus). That is the limited scope of this post, but I also noticed the link to “20230608-CDC-IP_Workgroup_HICPAC-FINAL.pdf” which, if I read it correctly, is a slide deck that proposes and seeks to justify the entire guidance that HICPAC will be voting on, August 22. This deck contains, on page 30, an enormous Gish Gallop of anti-mask papers — and, I would bet, no papers supporting them[1] — which I will have to systematically examine before that date. But not today!

Today, I want to understand what MRSA is, whether MRSA is airborne, and, if so, whether CDC’s “Enhanced Barrier Precautions” will prevent MRSA from spreading in hospital or nursing home facilities. (“Enhanced Barrier Precautions” take place within a larger “default setting” of normal precautions, so I will have to understand those too.)

What is MRSA?

MRSA stands for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, a type of bacteria that is resistant to several antibiotics…. MRSA is usually spread in the community by contact with infected people or things that are carrying the bacteria. This includes through contact with a contaminated wound or by sharing personal items, such as towels or razors, that have touched infected skin.

MRSA, if your metric is death, is one of the more important nosocomial, or Hospital-Acquired Infections (HAI):

MRSA infection is one of the leading causes of hospital-acquired infections and is commonly associated with significant morbidity, mortality, length of stay, and cost burden.

The majority of data indicate that MRSA increases mortality and morbidity in seniors, nursing home patients and those with organ dysfunction. Individuals with end-stage liver disease, renal insufficiency and those admitted to the ICU have high mortality rates when there is an associated MRSA infection. The mortality rates vary from 5-60%, depending on the patient population and site of infection. More important, more patients with MRSA are now undergoing surgery, and in at least 40% of patients, a central line was the cause of the infection. Finally, about 60% of patients do acquire MRSA within 48 hours despite having no healthcare risks

Credit where credit is due, hospitals have steadily reduced MRSA infections. From the State of Delaware’s FAQ:

Fortunately, there has recently been a decline in serious MRSA infections. For example, from 2005 to 2014, the overall estimated incidence of invasive MRSA infections from normally sterile sites (i.e., blood, pleural fluid, etc.) in the United States declined by 40% and the estimated incidence of invasive hospital-onset MRSA infections declined by 65%. However, MRSA remains an important health care pathogen and preventing MRSA infections is a priority for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The CDC estimates that MRSA is responsible for more than 70,000 severe infections and 9,000 deaths per year.

Unfortunately, MRSA jumped when the Covid pandemic began:

MRSA infections had dropped for years, but the COVID-19 pandemic erased years of progress. During the pandemic, some infections caused by MRSA rose 41%, according to the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America.

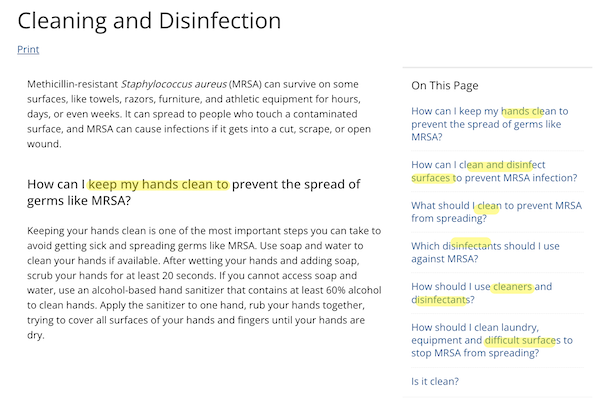

Given that MRSA is said to spread by contact (fomite transmission), hand-washing — Hospital Infection Control loves them their handwashing — is one appropriate remedy, along with disinfecting surfaces. From CDC’s page on “Cleaning & Disinfection” (last reviewed February 27, 2019):

But what if MRSA is also airborne?

Is MRSA Airborne?

Here is a list of studies suggesting that it is (with, sadly, some link rot, though generally searching on the title does the trick). For example, Journal of Hospital Infection, “Reduction in MRSA environmental contamination with a portable HEPA-filtration unit” (2006):

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of a portable high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA)-filtration unit (IQAir Cleanroom H13, Incen AG, Goldach, Switzerland) at reducing MRSA environmental surface contamination within a clinical setting. The MRSA contamination rate on horizontal surfaces was assessed with agar settle plates in ward side-rooms of three patients who were heavy MRSA dispersers. … Without air filtration, between 80% and 100% of settle plates were positive for MRSA… Air filtration at a rate of 140 m(3)/h (one patient) and 235 m(3)/h (two patients), resulted in a highly significant decrease in contamination rates compared with no air filtration…. In conclusion, this portable HEPA-filtration unit can significantly reduce MRSA environmental contamination within patient isolation rooms, and this may prove to be a useful addition to existing MRSA infection control measures.

If MRSA were not airborne, HEPA filters would hardly reduce it, amiright or amiright? Here’s another one, from JAMA, “Significance of Airborne Transmission of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus in an Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery Unit” (2001):

The MRSA samples were collected from the air in single-patient rooms during both a period of rest and when bedsheets were being changed. Isolates of MRSA were detected in all stages (from stage 1 [>7 µm] to stage 6 [0.65-1.1 µm]). About 20% of the MRSA particles were within a respirable range of less than 4 µm. Methicillin-resistant S aureus was also isolated from inanimate environments, such as sinks, floors, and bedsheets, in the rooms of the patients with MRSA infections as well as from the patients’ hands. An epidemiological study demonstrated that clinical isolates of MRSA in our ward were of one origin and that the isolates from the air and from inanimate environments were identical to the MRSA strains that caused infection or colonization in the inpatients.

Methicillin-resistant S aureus was recirculated among the patients, the air, and the inamimate environments, especially when there was movement in the rooms. Airborne MRSA may play a role in MRSA colonization in the nasal cavity or in respiratory tract MRSA infections. Measures should be taken to prevent the spread of airborne MRSA to control nosocomial MRSA infection in hospitals.

And one more, from Anesthesia and Intensive Care (PDF), “The Correlation Between Airborne Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus with the Presence of MRSA Colonized Patients in a General Intensive Care Unit” (2004):

Influence of bed making on loads of airborne and surface-associated drug-resistant bacteria in patient rooms” (2023):Air sampling directly onto a methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) selective agar was performed at six locations three times weekly over a period of 32 weeks in a new, initially MRSA-free Intensive Care Unit to examine if MRSA is present in air sample cultures and, if so, whether it is affected by the number of MRSA colonized patients present. A total of 480 air samples were collected on 80 days. A total of 39/480 (8.1%) samples were found to be MRSA positive of which 24/160 (15%) positive air samples were from the single rooms, where MRSA colonised patients were isolated, and 15/320 (4.7%) were from the open bed areas. A significant correlation was found between the daily number of MRSA colonized or infected patients in the Unit and the daily number of MRSA positive air samples cultures obtained (r2=0.128; P<0.005). The frequency of positive cultures was significantly higher in the single rooms than in the open bed areas (relative risk=3.2; P<0.001). The results from one of the single rooms showed a strong correlation between the presence of MRSA patients and MRSA positive air samples (relative risk=11.4; P<0.005). Our findings demonstrate that the presence of airborne MRSA in our unit is strongly related to the presence and number of MRSA colonized or infected patients in the Unit.

A transient increase in MRSA in room air was detected in most samples 1 min and 15 min after bed making…, Surface samples showed that MRSA… was isolated regularly in the patient environment. Correlation between airborne and surface pathogen loads after bed making was demonstrated. The study results indicate the importance of wearing a face mask in combination with cautious handling techniques when making the beds of patients carrying multi-drug-resistant bacteria. If the carrier status of a patient is unknown, consideration should be given to protective measures for staff and other patients present during and shortly after bed making. Surface disinfection should not be started until at least 30 min after bed making.

Duh, you have to let the bacteria settle before you clean the surfaces! (Of course, MRSA is airborne in factory farms — but not, apparently, in hospitals!)

Now, it’s clear that fomite transmission is a pathway for MRSA transmission — almost certainly the main pathway, given successful MRSA reductions in the past. However, unless we are willing to accept a level of continued MRSA transmission, it seems clear to me that airborne MRSA must be addressed, certainly at the level of the precautionary principles. And if the HEPA filters set up — one assumes — to trap SARS-CoV-2 also trap MRSA, is that so very bad? Or [dread word] the masks? (Of course, I have big priors on resistance to airborne, given the unconscionable and unscientific “massive resistance” to airborne transmission by WHO, CDC, and the Hospital Infection Control community. Another way of saying that is that these institutions have form. And not good form. Or accountability.)

Fortunately, the FDA has approved a mask that blocks MRSA. So now let’s turn to current precautions to prevent MRSA.

Do Enhanced Barrier Precautions Address Airborne MRSA Transmission?

We must fit Enhanced Barrier Precautions (EBP) within the larger framework of Infection Control as understood by CDC. From “Infection Control Basics“:

There are 2 tiers of recommended precautions to prevent the spread of infections in healthcare settings:

Standard Precautions and Transmission-Based Precautions.

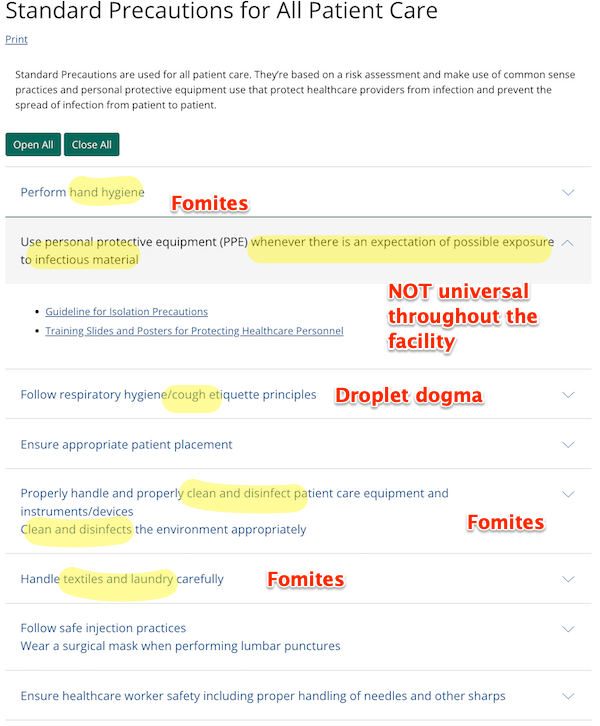

Standard Precautions (Page last reviewed: January 26, 2016):

Standard Precautions are used for all patient care. They’re based on a risk assessment and make use of common sense practices and personal protective equipment use that protect healthcare providers from infection and prevent the spread of infection from patient to patient.

More specifically:

Transmission Precautions (Page last reviewed: January 7, 2016):

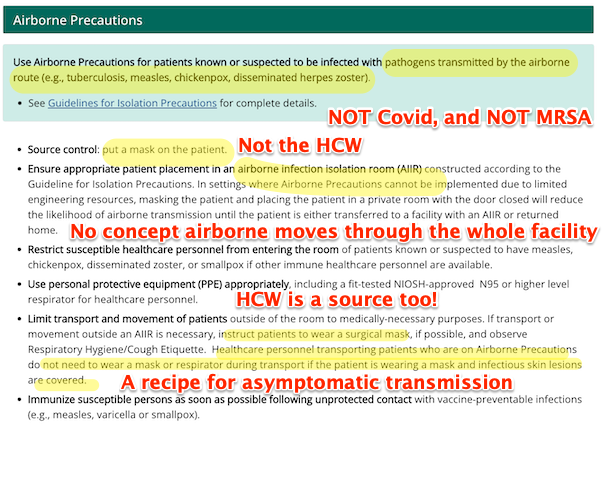

Transmission-Based Precautions are the second tier of basic infection control and are to be used in addition to Standard Precautions for patients who may be infected or colonized with certain infectious agents for which additional precautions are needed to prevent infection transmission.

Transmission Precautions at least has an airborne section. Here it is:

Obviously these “precautions” are wholly inadequate to prevent transmission of an airborne, asymptomatic Level 3 Biohazard (SARS-CoV-2) that moves like smoke through the entire facility. I’m not sure they’re adequate for MRSA either; that MRSA rose by 41% during the early phases of the Covid pandemic would argue no. (Isn’t it amazing how these “Precautions” don’t take account of the Precautionary Principle?)

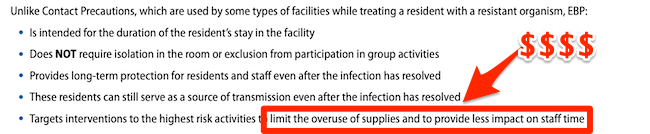

And now we arrive at “Enhanced Barrier Precautions”, which are a third tier of Precautions for Andrew “Ratface Andy” Cuomo’s death traps nursing homes only. From the CDC’s FAQ:

What are Enhanced Barrier Precautions?

Enhanced Barrier Precautions are an infection control intervention designed to reduce transmission of multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs) in nursing homes. Enhanced Barrier Precautions involve gown and glove use during high-contact resident care activities for residents known to be colonized or infected with a MDRO as well as those at increased risk of MDRO acquisition (e.g., residents with wounds or indwelling medical devices).

What are the differences between Enhanced Barrier Precautions and Standard Precautions?

As part of Standard Precautions, which apply to the care of all residents, the use of PPE is based on the “anticipated exposure” to blood, body fluids, secretions, or excretions. For example, gloves are recommended when contact with blood or other potentially infectious materials, mucous membranes, non-intact skin, or contaminated equipment could occur. A gown is recommended to protect skin and prevent soiling of clothing during procedures and activities that could cause contact with blood, body fluids, secretions, or excretions.

Enhanced Barrier Precautions expand the use of gown and gloves beyond anticipated blood and body fluid exposures. They focus on use of gown and gloves during high-contact resident care activities that have been demonstrated to result in transfer of MDROs to hands and clothing of healthcare personnel, even if blood and body fluid exposure is not anticipated. Enhanced Barrier Precautions are recommended for residents known to be colonized or infected with a MDRO as well as those at increased risk of MDRO acquisition (e.g., residents with wounds or indwelling medical devices). Standard Precautions still apply while using Enhanced Barrier Precautions. For example, if splashes and sprays are anticipated during the high-contact care activity, face protection should be used in addition to the gown and gloves.

See anything about airborne there? Masks? Thought not. Kevin Kavanaugh once more:

EBP allows contact precautions only to be used some of the time, and the resident is allowed to roam around the facility. “Residents are not restricted to their rooms and do not require placement in a private room.” Even with low transmission risk activities, such as passing medications, these activities are performed so frequently that transmission can still occur.

Enhanced barrier precautions and not advocating for admission screening of major pathogens is the opposite of determining and modifying a patient’s microbiome to prevent spread to other individuals.

Once again, there is no concept that whatever is airborne can — certainly with SARS-CoV-2, possibly with MRSA — spread throughout the facility.

Conclusion

Why then, given that airborne tranmission is a massive loophole for all CDC’s tiers of precaution, are Enhanced Barrier Precautions even being adopted by health (putatively) facilities? The letter announcing CDC’s new EBP guidance provides a clue:

Money (musical interlude). Exactly as with CDC’s guidance on school ventilation, as I show here. So if somebody in your care is in a nursing home and gets MRSA, remember that CDC didn’t protect them from airborne tranmission, and why.

NOTES

[1] Abaluck et al., where a natural experiment permitted a randomized trial is not listed, oddly. Or not.

Could be that the rise in MRSA tracks with the well-documented break down of “good order” in hospital systems world wide. I recall the horror stories of gurneys crammed into hallways and ICU nurses burdened with 4 or more patients at once. The lack of PPE, as well (nurses wearing garbage bags).

I also wonder if MRSA might be finding new frontiers now that covid “let rip” has battered open the immune gates. Airborne MRSA would, of course, make for easy spread among the newly vulnerable.

Lambert, the challenge is that our scientific community likes to study one variable at a time. In the case of a pathogen we like to put them into little boxes Fomite, Droplet, Airbourne, person to person. We will look at “primary” mode of transmission and will lose track of secondary modes.

We have to consider that a pathogen that is initially a droplet will eventually settle on a fomite and can then be aerosolized through secondary action. In any case a combination of ventilation, respiratory protection, cleaning and disinfection, isolation, identification, hand hygiene and basic design are all required to prevent transmission.

I think there’s an institutional mindset as well, that I haven’t yet concisely characterized or named. Think of the CDC tiers, which are in essence a tree structure, branching out to precautions like EBP. Same with spaces, where AIIR rooms are a subclass of room, the hospital is divided into medical and administrative areas, etc. Each node in each tree has PMC gatekeeper/expert/rent collector in charge of it. This model is not a disaster, at least not completely; they have, after all, achieved some success with MRSA. But it’s completely incapable of coping with airborne pathogens that float through the entire facility. They can’t even conceptualize that. That’s my amateur sociologist’s view, which people with actual knowledge can correct!

Endless appeal of “one weird trick.” False polarity and suchlike.

To be generous, one thing at a time is useful, up to a point.

My father was a Biochemist (elected member, Nat. Acad. of Science 1986). I have read interesting Science, my entire life. I am impressed with the references, organized thought process and the topic of your analysis. I thought it was a fascinating read. Indeed, the CDC does not fail by accident.

Quick note about nosocomial infection, it includes patients that infect themselves. If your a MRSA carrier and you get surgery done, and the wound gets infected by your own MRSA, then that counts as nosocomial. I don’t remember the actual number but maybe 1 in 5 people are S.Aureus carriers(nasal). It’s been years since I read up on this, so maybe new studies have been done.

«Now, it’s clear that fomite transmission is a pathway for MRSA transmission — almost certainly the main pathway, given successful MRSA reductions in the past.»

Call me a conspiracy theorist, but if I were an MBA running a major hospital chain, I would see Paradam’s observation as a justification for not reporting 20% of MRSA infections as nosocomial. I wonder how they got the other 20%?

An improvement on Rule #2: “Go die!” [We’ll bill your estate later.]

Great work, Lambert!

> Quick note about nosocomial

It does, and the percentage of the population who are carriers is in the double digits, at least (too lazy to find the number).

I recall being told MRSA was only airborne if a patient had it in their lungs and coughed, etc. But, seems to me, if you have it in your nose that might spread it via air. I always avoided drinking ice water in hospitals, as many places dispense ice from coolers on carts. Aides usually drop the scoop back into the ice and I doubt they ever wash their hands. Another source could be shaking out bed linens and those dusty room dividers.

The URL in this sentence appears to be invalid.

Yes I would like to know which mask blocks MRSA.

This post, besides the MRSA focus — important if someone you know is in a nursing home, heaven forfend — also clearly shows how deeply embedded anti-airborne/anti-mask ideology is embedded in CDC guidance; I expect HICPAC to reinforce these anti-science, lethal tendencies at its August 22 meeting. So this is, as it were, a shaping operation preparing the ground for further assault.

My wife contacted MYRSA during a hospital stay. They treated her with an old surfer based medication. It cured it.Apparently some older antibiotics are effective against diseases resistant to newer antibiotics.The biggest negative to taking these older medications is they have more side effects.I once had a doctor tell me that the best thing for someone in the hospital is to be discharged as soon as possible.He said all kind of diseases are spread in hospitals.This was 20 years ago. I bet today no doctor would tell you this.

Is “surfer based” auto-correct for “sulfa-based”? Such as the medications mentioned here, for example (trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole, a/k/a TMP and SMX. or by the brand names Bactrim and Septra)?

https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2011/0815/p455.html