Spain’s general elections this Sunday (July 22) could be a milestone event — of the bad rather than good kind.

If the latest polls are right — and, of course, they may not be — the until recently reasonably fringe party VOX could be about to become the first far-right party to enter national government since the dying days of Francisco Franco, in 1975. This it will do by becoming the junior partner in a coalition government with the conservative People’s Party (PP), as has already occurred in numerous towns, cities and regions across Spain in the wake of local and regional elections in May.

In such an outcome, Spain’s new prime minister will be Alberto Núñez Feijóo, the former president of Galicia’s regional government and current leader of the People’s Party. And he has a dark, shady past that he is trying his damnedest to downplay.

A Smuggler’s Paradise

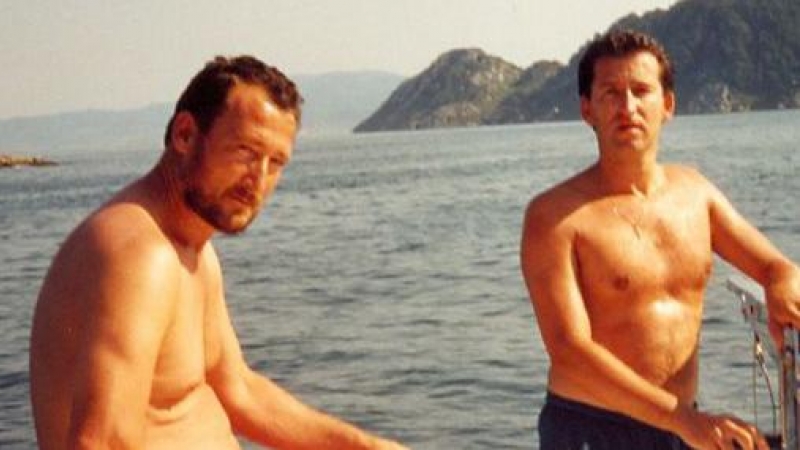

That past was brought into sharp relief by El Pais’ publication, in 2013, of a series of leaked photos from 1995 showing Feijóo, then deputy health secretary of the region, enjoying both a luxury yacht cruise and a mountain road trip with Marcial Dorado, a known smuggler and then-suspected (and later convicted) capo of the Galician drug-smuggling mafia.

Dorado is on the left, Feijóo on the right:

As I reported for WOLF STREET at the time, Galicia has long been a smuggler’s paradise:

Perched on Spain’s rugged North-Western coast and boasting a wealth of hidden bays and isolated beaches, Galicia has long been one of Europe’s most important entry points for contraband merchandise.

“It’s a historic tradition here that really took off in the late 1960s, early 1970s, with American tobacco,” Susana Luana, a journalist for the regional daily Voice of Galicia, told the BBC. “A number of local fishermen used their fishing infrastructure, including boats, to transport the goods and used their knowledge of the thousands of tiny coves and beaches here to bring them safely ashore.

“Later they increased their earnings considerably by smuggling drugs instead of tobacco. These former fishermen established a name for themselves as professional smugglers and so were able to make lucrative deals with the Colombian cocaine mafia.”

Much like Mexico, Galicia has become an indispensable link in the 21st century narco-traffickers’ distribution chain. And like their Mexican counterparts, Galician drug smugglers seem to have furnished cosy ties with key figures in the local and regional government.

Not that the revelation of said relations seems to faze Nuñez Feijóo, who in a recent press conference resorted to the Partido Popular’s now-standard defence against corruption charges: namely, to play dumb and deny all possible wrong doing, even as evidence mounts to the contrary.

“The photos are what they are: photos. There is nothing behind them,” said Feijóo. “No connection whatsoever to contracts with the Xunta [Galicia’s regional government] or the health department, or party funding.”

A Flimsy Defence

That last statement is an interesting one given that Galicia’s health department, of which Feijóo was then deputy secretary, was already doing business with Dorado. The department had signed a contract to purchase diesel and gasoline for the region’s hospitals and ambulances from companies belonging to Dorado. At that time, Dorado owned several gas station companies whose diesel and gasoline he used to power the fishing boats, gliders and trucks that transported his merchandise (which he still insists to this day was only contraband tobacco). He also used the companies to launder the proceeds from his smuggling/trafficking operations.

Feijóos’ defence rests on the three-pronged premise that he had no idea whatsoever of his host’s criminal past or his current line of work. And anyway, they barely knew each other — a claim that Dorado has consistently denied. As defences go, it is pretty flimsy, as I concluded in my WS article:

Even in these times of political decadence, debauchery and ineptitude in Spain, Feijóo’s assertion that he was completely in the dark about Dorado’s line of business beggars belief. After all, when most normal people meet a new acquaintance, the conversation inevitably turns to the matter of one’s vocational calling. “How do you do?” quickly morphs into “What do you do?”

Such basic formalities should hold even greater weight for a junior government minister whose actions are, or are at least supposed to be, subject to official codes of conduct and public scrutiny. As such, Feijóo is guilty, at best, of woeful political judgement and incompetence and, at worst, of knowingly consorting with criminal elements. Either way, in any self-respecting democracy – which obviously excludes present-day Spain – Feijóo would have walked, or been pushed, as soon as the allegations were made public.

That didn’t happen. Instead, Feijóo stayed in his job, went on to become leader of the PP and is now on the verge of becoming prime minister of Spain. And he refuses to change his story regarding Marcial Dorado. As for Dorado himself, he continues to insist that he and Feijóo were close friends. As he told the journalist Jordi Evolé in 2020, not only did the two of them — and their respective partners — travel together several times; Feijóo even slept over at Dorado’s house, and Dorado’s wife made him breakfast the next morning.

Narco Funding of Spain’s People’s Party?

At that time, Galicia’s drug traffickers operated with almost total impunity, often in cahoots with the security forces and local authorities. Given these operational advantages as well as its strategic location, Galicia quickly became the gateway for roughly 80% of all the cocaine that entered Europe. It also became a key point of entry for consignments of hashish from North Africa. These illicit trade flows generated huge sums of money, not just for the drug traffickers but also local businesses, corrupt politicians and law enforcement officers.

Even local publications have pointed to meetings between well-known crime bosses and the People Party’s founder (and former Francoist minister), Manuel Fraga, and former Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy (2011-18), both from Galicia. In fact, the People’s Alliance (AP), the precursor to the People’s Party, was first founded in Galicia, in 1989. In 2011, it emerged that the People’s Party of Galicia had staged a campaign event in 2009, featuring then-national party leader Rajoy, on a boat belonging to the Os Caneos family, one of Galicia’s most powerful drug trafficking clans.

In 2017, Laureano Oubiña, a well-known hashish trafficker who served 22 years in prison on a string of charges including money laundering and drug trafficking, said:

“I financed the People’s Alliance, like other Galician businessmen who were not involved in smuggling.”

Meanwhile, back in the ’80s and ’90s the drug epidemic in Spain was either ending or ruining the lives of untold thousands of young Spanish people, including in Galicia. In the absence of action from, or in some cases collusion of, local authorities, a group of brave Galician mothers rose up against the powerful drug traffickers. Spearheading the movement was Carmen Avendaño, who became president of the Érguete (meaning “get up” in Galician) Foundation. According to her, Feijoo’s claims that he didn’t know that Dorado was a major drug trafficker are not very credible, given Dorado’s business activities were common knowledge in Galicia’s coastal communities:

First they arrested him for tobacco smuggling, he even went to Portugal to evade conviction; then it was said, with great certainty, that he, along with Pablo Vioque [a drug trafficker who became secretary of the Chamber of Commerce of Vilagarcía de Arousa], had moved onto laundering drug money.

Avendaño is not the only person to have questioned the veracity of Feijóo’s claims. Manuel Fernández Padín, a repentant drug trafficker who testified as a protected witness in the Spanish Police’s Nécora operation (1990-94) against Galician drug trafficking clans, told the Spanish daily El Plural that it is “almost impossible” that Feijoo didn’t know Dorado was trafficking drugs (emphasis my own):

The photos are from 1995, after the Operation Nécora trial. By then it was already well known that the smugglers had moved on to drug trafficking; the entire Galician coast knew who was who. Everyone in Galicia or in Pontevedra knew… [A]t first those who made money from tobacco smuggling switched to hashish or cocaine while they continued to share a table and tablecloth with the politicians of the time.

While there may be no smoking gun to prove that Galician politicians were on the take, there are certainly plenty of witnesses pointing in that direction. And the People’s Party has spent the last decade or so lurching from one corruption scandal to another, most of them related to illegal kickbacks and illicit public procurement practices. Corruption was arguably the main cause of the downfall of Mariano Rajoy’s government in 2018. From Wikipedia:

On 24 May 2018, the National Court found that the PP profited from the illegal kickbacks-for-contracts scheme of the Gürtel case, confirming the existence of an illegal accounting and financing structure that ran in parallel with the party’s official one since the party’s foundation in 1989 and ruling that the PP helped establish “a genuine and effective system of institutional corruption through the manipulation of central, autonomous and local public procurement.”

The initial public outcry over Feijóo’s relations with Dorado may have died down quickly ten years ago, but it has reignited in recent weeks, as Spain gears up for general elections. Yolanda Díaz, the leader of the left-wing party Sumar, has asked Feijóo to explain to Spaniards “what exactly were his relations with drug trafficking” during a decade in which thousands of young Spanish people died from drugs. “Explain to us relationship with Marcial Dorado when all of Spain knew who Marcial Dorado was”.

Díaz also urged Feijóo to “come to the [presidential] debate” on Wednesday and “explain it to us.” Feijóo, much like a certain sitting president in the US, has refused to participate in the pre-election debate this Wednesday.

Pemex Scandal

It would be bad enough if consorting with known criminals was the full extent of Feijóo’s past pecadillos. But it isn’t.

He was also implicated in a transatlantic corruption scandal revolving around Mexico’s state-owned oil company Pemex’s disastrous foray into ship-building. As I reported for WS in 2020, Pemex’s huge no-strings-attached investment in Spanish shipbuilding giant Ballesteros bore all the hallmarks of an indirect bailout that bled hundreds of millions of euros from Pemex’s balance sheet in return for nothing of real value:

In 2013, as Spain’s financial crisis was still biting, the country’s biggest private shipyard, Ballesteros, based in the north-western region of Galicia, was teetering on the edge of bankruptcy. Hundreds of jobs were on the line, at the worst possible time for Galicia’s president, Albert Núñez Feijóo: just before new elections. With the help of Spain’s then-president, Mariano Rajoy, negotiations were quickly arranged with [Pemex’s deeply corrupt CEO Emilio] Lozoya, who agreed to let Pemex buy up 51% of the shipyard for next to nothing (€5 million), but the dodgy fun started then.

Despite having bought a controlling stake in the company, Pemex decided not to exercise any control of the business, preferring to leave that to the other (Spanish) shareholders. It also became Ballesteros’ number one client, ordering the construction of two so-called floatels (hotel-boats for oil rig workers) for hundreds of millions of dollars. One of them, acquired for €175 million, Pemex never even used. The other, Pemex hasn’t used anywhere near full capacity.

In October 2019, Ballesteros went bankrupt once again. Pemex’s current CEO, Octavio Romero, says that the purchase was riddled with irregularities and has filed a complaint for fraudulent administration.

After his dismissal in 2016, Pemex’s CEO Emilio Lozoya ended up seeking refuge in Spain, whence he was eventually extradited back to Mexico, where he is currently languishing in jail on a string of corruption charges.

Passion for Privatisation

Even more concerning is Feijóo’s passion for slashing healthcare spending and privatising healthcare services. In fact, while the Community of Madrid, under the stewardship of PP “populist” Isabel Ayuso, is now at the leading edge of this privatisation process, Feijoo’s government in Galicia was an early pioneer. According to the Spanish daily Publico, in his first four years in office (2009-2012), the now-leader of the PP slashed the healthcare budget by 8.6%. When Feijóo resigned as head of Galicia’s Xunta in 2022, healthcare spending in the region was, in real terms, still lower than in 2009.

Predictably, waiting lists have soared as spending has shrunk. During the pandemic, Feijóo closed several rural health centres in Galicia. In their place, his government — much like the UK’s — prioritised telephone and online consultations (despite the fact that the aged population in rural areas represents a major obstacle to this type of of attention).

The biggest beneficiaries of the systemic impoverishment and dismantlement of Galicia’s public healthcare sector have been large Spanish and foreign (mainly US) healthcare multinationals. They include Quirón, Hospitales de Madrid, Vithas, Ribera Salud, Medtronic and Centene. After 13 years of the Feijóo government, private hospitals in Galicia provide 26.5% of specialised and hospital care, 28.5% of interventions with hospitalisation, 40% of major ambulatory surgery operations, 29.8% of emergency care cases, 20% of admissions and 26% of outpatient consultations.

The People’s Party is not the only party in Spain that supports the mass privatisation of healthcare. In fact, the main party in government, the so-called Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE) and its coalition partner, Podemos, have drawn up legislation that would hand all medical care for workers and the self-employed to mutual societies. It would be the biggest sell out of the public healthcare system since its creation. According to WSWS, “mutual societies would become the backbone of the health service and would be responsible for the medical care of 90 percent of Spain’s working population.”

All of which serves as a reminder that on many of the most pressing issues of our time — from the privatisation of public services to the war in Ukraine, to the backfiring sanctions on Russia, the sanctity of the transatlantic alliance and the need for ever greater control, manipulation and censorship of the masses — most major parties in Europe, including those that dominate the EU’s power structures, are on the same page.

But the outcome of Sunday’s election in Spain could still have far-reaching implications. If Feijóo comes out on top but is unable to secure a majority and hence opts to form a coalition government with VOX (still a largish “IF”), Spain is likely to witness not only the emergence of a whole new form of “Kleptokakistocracy” (government by the worst, least qualified, and most unscrupulous) but also the return to national government of the far-right in a country where the scars of the Civil War and Franco dictatorship are still dangerously fresh.

I can attest to to this. For six or seven winters before the pandemic, Juana and I visited our daughter who was self-exiled in Spain. Lured by the rhetoric of Podemos and affordable housing in the midst of the Spanish real estate collapse we gave serious thought to expatriating.

Until we joined a large intercambio (language interchange) with dozens of Spanish senior citizens. A majority of these remembered Franco fondly, most especially for “giving the workers a thirteenth paycheck”. Of course this only meant that their annual pay had been divided by 13 rather than 12, but the affection was palpable.

A second intercambio with dozens of twenty and thirty somethings was equally ardent. Like father, like son. We abandoned plans of expatriating.

An impressively documented article from Nick, with good analysis, as always. On the side-issue of the Civil War and Franco dictatorship, I always noticed the indecency with which the Spanish right, at least members of it who express themselves publicly, likes to openly disparage and make fun of the mourning and memories of people who lost relatives in the Civil War or otherwise claimed for justice. It is also true, of course, that the PSOE did little, under Felipe González, to bring that justice or at least official recognition, when it could still be done, i.e. when the criminals were still around.

On the main theme of the article, if Covid has shown anything, it is the total moral corruption of 95 plus percent of European politicians. Feijoó just goes one step beyond with his narco ties.

As one who lived in Spain for several years after growing up in Los Angeles, I can attest that the tail end of Francoism in the mid Seventies was great. Streets safe at any hour in any neighborhood, familes venerated, poor people had huge amounts of housing built for them, great public transit and trains between cities, even back then.

Autarky forced on Spain by the U.N.’s sanctions meant the country was self sufficient and even had a burgeoning environmental movement, recycling for example and all detergents had to be biodegradable. Now the country is run by a bunch of handwringing feminists who make sexual harrasment the most important thing in the nation. Look forward to a change in government.

I would suggest that “the tail end of Francoism in the mid Seventies was great” because it was generally great in Western Europe, with admittedly this or that plus from an orderly society as Spain was in the mid-Seventies (with the minuses of a repressed society, including the repression of regional/national cultures). Remember, the early Seventies were the best time economically in Western Europe generally, and it was all downhill for industry from the oil crisis onwards. In Spain too. It was just a coincidence that the Franco regime ended at about the time that the general economic crisis started in Europe. If Franco had lived on, Spain would have suffered the same desindustrialization that it did under “democracy”. And: the rapid and violent societal change that Spain suffered after 1975 showed that Spanish society was not that strong and stable at the end of the Franco regime. If Franco had lived on, he would have transitioned to neoliberalism and general social destruction like everybody else. I don’t think that man needs to be idealized, under any aspect. Like saying Hitler created millions of jobs, which he did.

No. There was an extraordinary burst of creative energy, excitement among ordinary people. Intellectual hunger was enormous, and people were having sex, talking late into the night, crawling the streets and staring at one another with open interest. Barcelona was, for a stretch, the most exciting city in the world.

I was all over Europe at the time, and there were not many places like it. Perhaps Berlin.

Yes. This situation was full of contradictions. Felipe Gonzalez traveled to Paris for a series of clandestine meetings with the CIA where he made certain promises, probably not to socialize certain industries, in exchange for promises (it is assumed) not to interfere by the U.S.. A lot of the apparent progressivism cited above was naive; much of the hunger, as with Moscow after the fall, was for the trappings of middle class life, little more. (Though you cannot fault people for wanting their children to eat well, to be secure.) Much of that intellectual excitement owed to a left newly freed to tell its stories of repression. Spain failed, for a long time, to come to grips with the tens and tens of thousands of its relatives, still lying all over the place in shallow graves. Regionalism re-emerged–the Basque Country, Catlunya, Galicia, and even Andalucia blossomed; this flowering also had a middle class character and downside, but was real.

Today, Spain has too much unsettled business. The same profound cleavage between left and right remains. After the very real explosion of life there, the resaca (hangover/wave returning to the ocean). After the resaca: A country, like all the EC countries, without the economic sovereignty to solve its own problems.

The usual cycle prevails: the left and progressives arouse hope, cannot deliver. Resentment and right-wing solutions take their turn.

I have lived in Spain for six years now, and I am still constantly amazed at what I learn about its history/politcal system. I think that the post-Franco “Law of Forgetting” as described in the recent documentary The Silence of Others (highly recommended by the way) is a big driver of these issues. The younger generations are not taught about the dictatorship, and they genuinely do not know the history of their own country. In effect, each person tends to follow their parents’/grandparents’ position because that is the only place they can get the information.

As for the upcoming elections, I would not be surprised to see a PP/Vox government coalition, but I think that will be avoided for now. Unfortunately, as in the rest of Europe, the economy is not improving here, and the so-called left is doing little in that regard, so the future likely belongs to the right.

Interesting times…

> … the so-called left is doing little in that regard

This … fueling my unending state of depression … as such pertains to rising up against oligarchy everywhere. #WTF

Yes, that must be the same “Law of Forgetting” that forbids USian teachers from telling their students about how Henry Ford proudly accepted the Iron Cross bestowed upon him by Hitler.

Thanks a lot for this, Nick. It makes me recall several good summer seasons i spent in Isla de Arosa (Illa de Arousa) in the early 80s. Then, trafficking consisted mostly on american tobacco and some hashish. I remember one night in a tiny little beach in Arosa when you could hear the roaring of engines and see lights amongst the platforms where mussels are cultivated we had the company of Guardias Civiles (kind of national guards) saying. “Busy tonight, isn’t It?”. Everybody knew. And the names of the traffic capos was well known in Galicia. Feijoo claiming ignorance has 0 credibility. Few years later cocaine was King.

And here we are now. Galicia has always been a stronghold of the People’s Party. The Party that always serves the interest of the PMC to the extreme of being their leit motif. What is good for our companies, they claim, is good for Spain. The perspective of 4 years of inept and corrupt PP leadership is anything but attractive.

Hi Ignacio. I’d be interested in reading your take on Yolanda Diaz and Sumar. Watching a few of her rallies and speeches I was thinking it was sad that there is not one prominent US politico who would take their positions, and with apparent popular support. Will the powers that be make sure Sumar does make any progress (a la Bernie Sanders)?

IMO, SUMAR will almost certainly follow the typical path of progressive left: become assimilated by the PMC or stay politically irrelevant. Remember TINA and the fate of Sanders, AOC etc. Western democracies do not allow for anything outside the neoliberal path. Let’s admit the fact.

Serious question: Is having your political party financed by smugglers any more distasteful than accepting contributions from Zuckerberg, Exxon and Charles Koch?

One thing that Politicos of all stripes agree on; the patina of respectability is necessary to claim legitimacy. So, alas and alack, being funded by socially entrenched oligarchs is preferable to being funded by first generation smuggler money. (How Kennedy finessed that family history is an object lesson in politics. Marrying a major East Coast debutant helped.)

Perhaps Feijoo can marry into the minor nobility of Spain.

What’s not to like when you learn that the CIA self-funded at its inception by drug trafficking?

The Politics of Heroin – McCoy

Is there anywhere on this planet not corrupted by the US oligarchs and their servants – the CIA, the other secret service alphabet agencies, the Dems, the GOP and the weapons makers and sellers and users?

Russia? China?

Iran?

Russia? China?

Feijóo doesn’t need to dawn play his connection to drug lord Dorado. The Spanish media has his back. The majority of the judges have his back too. The Spanish state still lives under Franco’s rule more than 50 years after the dictator’s death.

The Popular Party is running on filthy lies and the promise to take back gender affirming bills and the like. The press is happy with the prospect of a fascist government as long as they keep their their pockets filled with public funding.

Diesel powered gliders for trafficking?!? Meow?

Anyway, nobody of influence and authority in Spain, Europe or the US will care what Feijóo did in the past (except as it might be useful for blackmail), nor will they care about his alliance with the far right, as long as the Spanish government does not question Spain’s Atlanticist orientation in general, or ongoing and increased support for the war in Ukraine in particular.

::applause::

Thanks for this, Nick.

A wonderful, informative read.

Thank you Nick, I am glad that this kind of information is getting out to the ¨wider world¨ such as it is. I too am a refugee from the US of A – it got to where I could not stand to hear that whiney voice of GW Bush another day. I too was encouraged by the emergence of Podemos, but was not quite as discouraged as some by their failure to take off to the extent desired. The media smears, government falsifications and lawfare arrayed against them was impressive.

That said, Spain is a deeply conservativve country. Centuries of domination by the Cathoic church and the forty years of Fascist dictatorship has left its mark.

Feijoo is a piece of work. He has, as they say here, solo dos dedos de frente. His program is to defeat what he calls ¨Sanchismo¨, as if Pedro Sancez were Hugo Chavez – undo the last four years of legislation. In the opinion of many who have more experience than I as to Spanish politics, the current PSOE/Podemos government is the best in many years. Not that I am a great fan of Pedro Canchez, he is an austute politician who knows which way the wind blows and moves accordingly.

Every week I discuss with my son, who lives in the US, the politics in both places. I think that both are consumed by neoliberalism and driving the countries to ruin. The difference is that (I think) the general Spanish people are a little more aware of what is going on, but don´t know how to fix it. There is some kind of underlying value system, some kind of basic human decency or solidarity that, though greivously abused, is still there. It gives me a little hope. The americans, on the other hand, out there in their raw new continent, have not yet grasped this essential fact. When my son was here last we were out in town and he popped up with – over here there is a real society.

Lets hope that the good guys win because as Nick says, it will be back to the bad ol days if they dont.´ The thing that really surprises me about the current government is that, while denouncing the far right parties as Fascists to be avoided at all costs, they our total support to an openly corrupt, Fascist country thousands of miles away! (I think that may be due to the experience depicted in the great Berlanger film ¨Bienvenido Mr. Marshall¨.

Thanks Nick, horribly depressing but otherwise a great piece. Particularly this paragraph broke my heart:

The People’s Party is not the only party in Spain that supports the mass privatisation of healthcare. In fact, the main party in government, the so-called Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE) and its coalition partner, Podemos, have drawn up legislation that would hand all medical care for workers and the self-employed to mutual societies.

Whoever still believes that there is anything redeemable about Western polities, and still puts hope in their left-ish parties, I give you exhibit 1: Syriza… exhibit 2: Bernie and the Squad… exhibit 3: Podemos… seemingly on its way to privatize the healthcare of Spain!

And what happens when a left-ish politician builds a successful movement but doesn’t sell out? And I give you exhibit 4: the crucifixion of Corbyn, whose political career was completely destroyed, and whose followers were thrown out of the party.

It’s funny, in Greece we have the Mitsotakis that has family ties with a known 2 ton dugs smuggler, shipping mogul, TV-newspapers-sites-football team owner, named Marinakis.

The trial for the super smuggling that was found out in 2013, never came to fruition. 11 or 12 witnesses “died” and numerous justice officials resigned and one migrates to the US.

Yet again Mr C skewers an important EU story (this one being also relevant to neighboring Portugal with its weird drug use policy ‘legal for the important ones’ – so never properly controlled and now rampant drug problem), …… adds herbs and spices; gently grills it then presents it for us to chew over.

One perhaps interesting addition to the mothers ‘Getting it Up’ (?) might be the attempts by other Galician ‘Forces of the Light’ to combat the ‘Forces of Darkness’ by, amongst other things, burying their story within that Spanish epic Don Quixote …. look for both a film and other writings.

A Bard AI search using : who hid the story in don quixote altering every 3rd or 4th letter about corrupt galician politician and mafia that was later prosecuted

The story in Don Quixote about corrupt Galician politician and mafia that was later prosecuted was hidden by Manuel Rivas. He is a Galician journalist and writer, and the author of the book Os señores da guerra (The Lords of War), which was published in 1991. The book tells the story of the Galician mafia, a powerful criminal organization that was involved in drug trafficking, extortion, and murder.

Rivas hid the story in Don Quixote by altering every third or fourth letter in the text. This created a secret message that could only be read by those who knew how to decode it. The message was eventually revealed, and it caused a scandal in Spain. However, Rivas was not prosecuted, as he had hidden the story in a way that was not considered to be libelous.