Yves here. In the US, at least according to the press, the climate change effect on housing prices has affected properties on flood plains and exposed to storm surges and potentially wildfires. This paper says heat is a factor too.

By Michele Cascarano, Economist Bank Of Italy and Filippo Natoli, Senior Economist Bank Of Italy. Originally published at VoxEU

Climate change is shaping housing preferences. This column uses data on online housing advertisements and in-person appointments of buyers and sellers with estate agents in Italy to show that a higher number of hot days in a month temporarily shrinks online and physical search, and leads to a permanent fall in average house prices. The latter effect is driven by a decrease in the price of houses that are not considered climate-resilient, suggesting a preference shift towards energy-efficient, cost-saving housing.

As the world grapples with the multifaceted challenges posed by climate change (Weder di Mauro 2021 Blanchard and Tirole 2022, Natoli 2023), a lesser-known impact is emerging in an unexpected realm: housing markets. While discussions on housing and climate often revolve around the longer-run risks of sea level rise, there is no evidence in the literature on the effects of extreme temperatures, which are known to negatively affect people’s health (Carleton et al. 2022), labour productivity (Somanathan et al. 2021), and human behaviour more generally (Busse et al. 2015), on house prices. In the housing market, temperatures can credibly influence the matching between buyers and sellers, as many parts of the housing search is conducted outdoors, exposing individuals to weather fluctuations.

In a new paper (Cascarano and Natoli 2023), we delve into the interplay between individual housing search processes and the aggregate shocks caused by extreme temperatures. To unravel this phenomenon, we curated a comprehensive dataset tracking 2 million online housing advertisements between 2016 and 2019, as well as in-person appointments of buyers and sellers with real estate agents across major Italian cities. Employing daily temperature data at the municipality level, we examine how an increase in the incidence of hot days in a month can affect search activities and, as a consequence, the number of housing transactions and prices. The estimates are carried out in a monthly panel setting, either at announcement level (when the target variables are online search and prices) or at city level (for transactions and in-person appointments), grasping the effect of hot temperatures over a 12-month horizon using local projections.

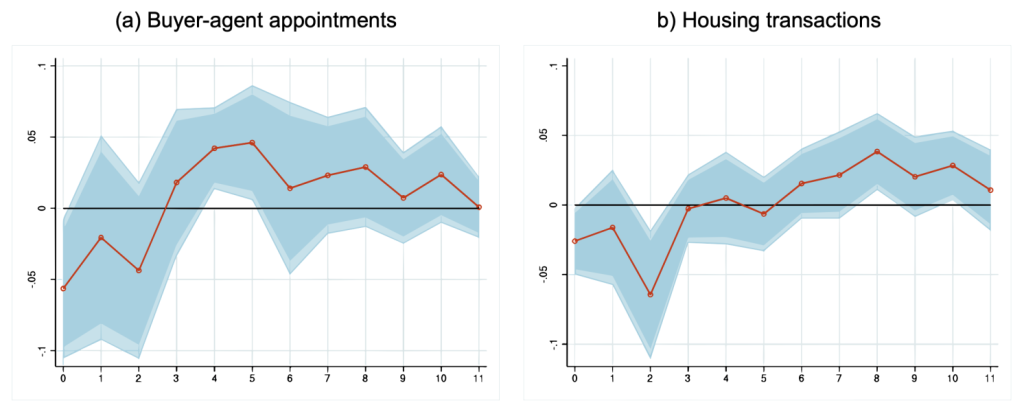

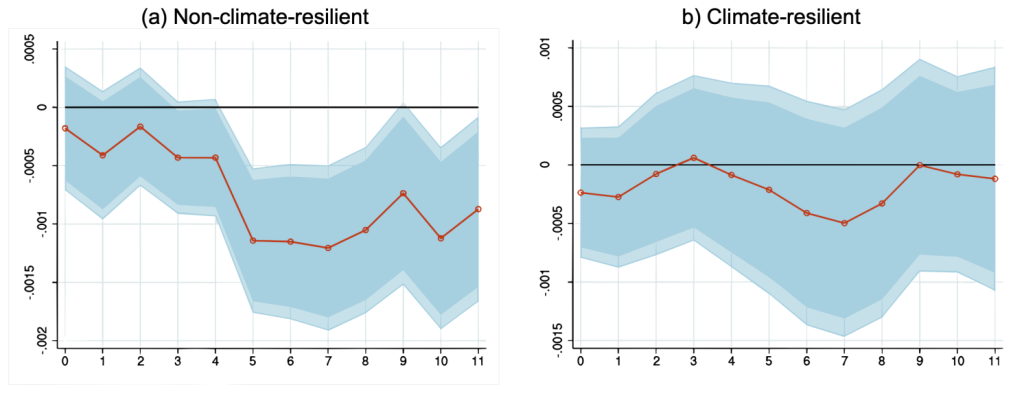

Figures 1 and 2 report the main results of the analysis. Figure 1 shows that an increase of the share of days with average daily temperatures exceeding 25°C in a month leads to a contemporaneous fall in the number of in-person visits to the houses for sale (Figure 1a), and to a fall in the number of housing transactions two months after (Figure 1b). 1 While these effects are temporary – searches resume after the heat – the downward revision in house prices appear persistent. At the root of these dynamics lie the unequal impact of temperatures on residential houses with certain climate-related characteristics. Indeed, by splitting the set of houses for sale into those with structural climate resiliency features – with high energy efficiency (that reduces heating and cooling costs) and outdoor spaces where people can cool down during heatwaves – and the rest, Figures 2 shows that prices decline five months after the shock only for non-climate-resilient ones (Figure 2a), while prices are not impacted significantly in the cases of resilient houses (Figure 2b). Other modifiable climate-related characteristics, such as the presence of an air conditioned system, are found to play a minor role.

Figure 1 Effect of temperatures on housing search and transactions

Note: Vertical axis is expressed in percent.

Figure 2 Effect of temperatures on the price of non-climate-resilient versus climate-resilient dwellings

Note: Vertical axis is expressed in percent.

All in all, Figures 1 and 2 suggest that hot temperatures induce two separate effects. On one side, they hinder search in the short run, acting as a friction in the buyer-seller matching process. On the other side, they redirect buyers’ preferences towards homes that are better prepared for extreme temperatures. This narrative aligns well with a ‘wake-up call’ effect of high temperatures, for usually inattentive agents, on the future economic risks of climate change, which has been documented in recent academic contributions (Hong et al 2023, among others).

This interpretation of the results is confirmed by two additional analyses. First, the different price effect across housing types is not driven by a heterogeneity in housing demand, as the same result also holds within the pool of houses with similar prices per square metre in each city, suggesting that the preference shift is broad-based across different housing clientele. Second, on contrast to houses for sale, hot temperatures do not induce significantly negative price effects in the rental market, where the shift in preferences is plausibly inconsequential due to the shorter-term nature of renting decisions.

While the average price drop per housing unit is arguably small – with average elasticity of 0.007% at the trough, or 0.2% for one additional hot day per month – the overall impact on the housing sector can be potentially large. Indeed, a back-of-the-envelope calculation based on the volume of housing transactions in Italy, worth €123 billion in the first quarter of 2023, suggests that one additional hot day per month might generate a realised loss in housing transactions of about €0.8 billion.

In sum, our study’s findings illuminate a hitherto unexplored facet of the influence of climate change on housing markets by introducing a short-term, climate-related driver of house prices. Temperature variations wield the power to influence housing search patterns on a broader scale, underscoring the far-reaching nature of this phenomenon. Importantly, households seem to value the risks associated with the ongoing climate change and seek ‘climate safety’, as has been found with financial investors directing their funds into countries at lower climate risk (Ferriani et al. 2023). This observation injects a new dimension into conversations aroud climate-related financial vulnerabilities for households.

Authors’ note: This column does not necessarily reflect the views of the Bank of Italy or the ESCB.

See original post for references

Maybe because air conditioning became so prominent, but why the southwest never bothered with window shutters is a bit of a mystery to me, particular in Mediterranean climes such as here.

Lots of houses here in Phoenix have shutters. They are usually about 6 inches wide and glued onto the tyvekstucco exterior wall, on either side of the window.

They’re not shutters if they don’t shut, they’re just a cosmetic effect.

Shutters are for hurricanes. For hot weather you need the pull-down metal blinds known as persianas.

I wonder how this will impact migration within the United States. For example, currently Miami has been/is seeing a huge surge in population due to the exodus from Chicago and New York by finance types.

At what point will trends like this reverse, and people with means begin moving north because they are hostage to air conditioning for half the year?

When the price of air conditioning becomes so high that people actually cannot even afford to pay it . . . as in . . . . they actually have to live in un-air-conditioned houses because they do not have the money to pay for air conditioning, then they will look into moving north.

It’s not much different from being hostage to frigid temps for half the year. The biggest difference is that the hot temps in Phoenix almost coincide with the peak solar generation times. The cold temps up north pretty much inversely correlate with solar.

Anyhow, here’s hoping the northerners panic and stop moving here.

Actually, I live in the North and during the winter I go for my three mile walk most everyday. It’s more enjoyable than the summer. I guess you can do that in Phoenix if you have a space suit or I guess they’re called earth suits.

The heat & humidity from like late June until, well, now, has been so oppressive here in Houston that I’ve started to hear people who were previously very pro-Texas start to talk about moving (or dreaming of having enough money to get a summer home up north).

The nighttime temps didn’t get below 80F for long stretches of time, so even going out for a walk or jog at night felt awful.

Even with AC, it sucks not being able to go outside like that.

Already happening, the Wisconsin real estate market has been hot this year, some it from people moving north from Texas which has been miserable for multiple summers in a row.

I see a Coober Pedy gig where 60% of the population lives underground in particularly hot locales in Arizona.

That was my impression of downtown Houston the one time I visited there for a conference back ca. 1990? Houston was very proud of its underground pedestrian tunnels and upscale shops (at least around the convention center). It was like living with termites. Once one ventured above ground there were only PoC.

Hard to replicate that in Miami. They can’t build down.

Houston tried to do me in on a number of occasions in its version of hell on earth, one time the humidity was so awful i’d lost so much weight in a day that I was able to sell my diet plan to the National Enquirer.

Compare and contrast with the tunnel system in Toronto and skyway system in Minneapolis, which they have in order to deal with the winter. Re Toronto: There’s a lot to be said for being underground where the surrounding temperatures are more stable and thus easier to control.

Further, to the point of the article conclusion, “suggesting a preference shift towards energy-efficient, cost-saving housing”, there is now required labelling of the energy efficiency rating of a building or house for sale in some locales (UK and NYC come to mind), which could have significant effect on the resale prices of units going forward.

The Netherlands is actually exploring limiting free market rents based on the energy rating; https://nltimes.nl/2022/09/23/tenants-poorly-insulated-homes-may-get-significant-rent-reduction

When I briefly lived in Houston in 1976 I saw a Chamber of Commerce pamphlet touting Houston as “the most air-conditioned city in the world!”.

It needed every last bit of it too.

“as has been found with financial investors directing their funds into countries at lower climate risk (Ferriani et al. 2023). This observation injects a new dimension into conversations aroud climate-related financial vulnerabilities for households.”

My view — Financial investors are the creators of ‘financial vulnerabilities for households’.

Keep tax favoring incentives for financial investors to keep goosing the price of shelter (just another way of saying – increasing the cost of living) and households become to expensive for the inhabitants – a vulnerability in my view.

As a child we lived in Nigeria, about a mile from the Ocean, and 5 degrees from the Equator. Our home was designed and built for the climate.

The was no wood in the structure, due to ravaging termites. It was all concrete with terrazzo floors, encased by insect netting.and because if the insect netting front and back, designed with through breezes. All rooms had ceiling fans.

Only the master bedroom had an ac system.

Such a house might work on the US Gulf coast and maybe in Southern California.

In the UK we did not have central heating, just a fireplace in the lounge, and dressed to keep warm.

The US has a difficult climate because of the extremes of temperature between summer and winter. Hence the focus on insulation and a/c.