On September 28, the Justice Department continued its efforts to reduce wage- and price-fixing cartels in the US economy.

This time the DOJ filed an antitrust lawsuit against Agri Stats Inc. for running anticompetitive information exchanges among broiler chicken, pork and turkey processors. Agri Stats allegedly collects, integrates and distributes price, cost and output information among competing meat processors, which allows them to coordinate output and prices in order to maximize profits. That, in turn, means grocery stores and consumers pay much more.

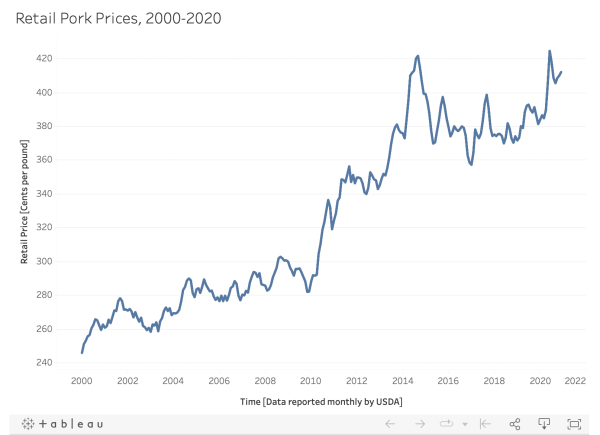

Here you can see what effect the information sharing has had on pork prices:

It sure took the DOJ long enough to get on the case as Agri Stats has been the subject of several private antitrust lawsuits in recent years. Details from Investigate Midwest:

Agri Stats — a widely utilized, privately-held data and analytics firm for the meat processing industry — has been named in more than 90 lawsuits since 2016, making it the second-most sued company in the industry over that time span (Tyson Foods is first). All the lawsuits accuse the company of facilitating anti-competitive behavior because, with the almost real-time data, meat processors can see what their counterparts are planning…

Most allegations are similar, even across industries. Meat producers “conspired and combined to fix, raise, maintain, and stabilize the price of” product, reads the first lawsuit, filed in 2016 on behalf of Maplevale Farms, a New York food service company.

Wholesale and retail price data from the USDA reflects a rise and stabilization in consumer prices since early 2008, when the conspiracy is alleged to have started affecting the market, particularly in pork.

Agri Stats paused its turkey and pork reporting in the face of these private antitrust lawsuits, but according to the DOJ, “has expressed an intent to resume such reporting after these lawsuits’ resolution,” and Agri Stats’ scheme continues to this day in the chicken processing industry.

It would be nice to see the DOJ go after price- and wage-fixing schemes that aren’t first uncovered by private lawsuits. To glean some insight into Agri Stats, they would have only had to walk a half mile across Washington DC to the US Department of Agriculture. That’s because the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service has long purchased data from Agri Stats. From Investigate Midwest:

While the terms of the contract aren’t perfectly clear, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, or APHIS, has purchased data from Agri Stats over the last decade — something that surprised [a former branch chief for the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service James] MacDonald, who worked in a different area of the USDA.

“Wow,” he said when asked about the government’s purchase orders. Because of meat production’s concentration and buy-in from the biggest companies, “Agri Stats is this industry statistics source in a way that you don’t really see anywhere else in other industries,” he said.

An APHIS spokesperson said the department purchased data to calculate indemnity values for poultry should animals need to be euthanized due to a disease outbreak.

“Agri Stats was chosen as a data source for APHIS to calculate the fair market value for various types of poultry because some of these animals are not commonly bought and sold on the marketplace, so price data is not publicly available,” the spokesperson wrote in an email.

That the data isn’t publicly available is the problem. According to the DOJ:

While distributing troves of competitively sensitive information among participating processors, Agri Stats withholds its reports from meat purchasers, workers and American consumers, resulting in an information asymmetry that further exacerbates the competitive harm of Agri Stats’ information exchanges.

MacDonald’s claim that “Agri Stats is this industry statistics source in a way that you don’t really see anywhere else in other industries” may have been true in the past, but it certainly isn’t anymore. It’s increasingly coming to light how widespread this “information sharing” is across the big players in the US economy. Pick a field and you can likely find cases of this type of price fixing.

One of the biggest is Texas-based RealPage, which is accused of acting as an information-sharing middleman for real estate rental giants. The company is facing several lawsuits contending that the property managers agreed to set prices through RealPage’s software, which also allowed the companies to share data on vacancy rates and prices in many of the US’ most expensive markets.

Many of the rental markets dominated by large landlords have seen astronomical growth in rental prices in recent years (even before the pandemic), as well as a rising number of evictions and spikes in homelessness. The lawsuits against RealPage and the rental management companies contend that its software covers at least 16 million units across the US, and private equity-owned property management companies are the most enthusiastic adopters of the RealPage technology.

Reporting, the lawsuits, and RealPage’s own statements showed that the company’s software said that it was often more profitable for mega landlords to have higher vacancy rates and keep rents elevated, which contradicted the old landlord practice of getting heads in beds even if that meant lowering rents.

Agri Stats, just like RealPage in the rental market, encouraged meat processors to raise prices and reduce supply.

Matt Stoller calls this the “price-fixing economy” and suspects that it is systemic across the country in every industry. It would be surprising if it wasn’t. In reality it’s hard to blame companies and middlemen for doing so, considering that the Clinton administration effectively legalized such schemes back in the 90s, and successive administrations failed to close the loophole.

That finally changed back in February, but first a quick review of the Clinton-era rule for “information sharing.”

In 1993, first lady Hillary Rodham Clinton and other officials announced steps to make healthcare more “available” and “affordable” to all Americans. The policy statements provided for antitrust “safety zones” which created circumstances under which the DOJ and the FTC would not challenge the following:

- Hospital mergers;

- Hospital joint ventures involving high-technology or other expensive medical equipment;

- Physicians’ provision of information to purchasers of health care services;

- Hospital participation in exchanges of price and cost information;

- Joint purchasing arrangements among health care providers;

- Physician network joint ventures.

These rules provided wiggle room around the Sherman Antitrust Act, which “sets forth the basic antitrust prohibition against contracts, combinations, and conspiracies in restraint of trade or commerce.”

And it wasn’t just in healthcare. The rules were interpreted to apply to all industries. To say it has been a disaster would be an understatement. Judging from Agri Stats and RealPage lawsuits, it is clear that companies increasingly turned to data firms offering software that “exchanges information” at lightning speed with competitors in order to keep wages low and prices high – effectively creating national cartels.

Recall that the same year HRC steered through the price fixing loophole, Archer Daniels Midland was prosecuted for rigging the international lysine market. Three of its officers were actually sent to prison back when the US used to do such a thing, and the company was fined $100 million, the largest antitrust fine on record at the time.

If there’s one positive that has come out of the Biden administration, it’s this: The DOJ finally admitted that these Clinton-era loopholes were a mistake and closed them back in February. Here is the Feb. 3 statement from the DOJ:

After careful review and consideration, the division has determined that the withdrawal of the three statements is the best course of action for promoting competition and transparency. Over the past three decades since this guidance was first released, the healthcare landscape has changed significantly. As a result, the statements are overly permissive on certain subjects, such as information sharing, and no longer serve their intended purposes of providing encompassing guidance to the public on relevant healthcare competition issues in today’s environment. Withdrawal therefore best serves the interest of transparency with respect to the Antitrust Division’s enforcement policy in healthcare markets. Recent enforcement actions and competition advocacy in healthcare provide guidance to the public, and a case-by-case enforcement approach will allow the Division to better evaluate mergers and conduct in healthcare markets that may harm competition.

In a Feb. 2 speech announcing the withdrawal, Principal Deputy Attorney General Doha Mekki explained that the development of technological tools such as data aggregation, machine learning, and pricing algorithms have increased the competitive value of historic information. In other words, it’s now (and has been for a number of years) way too easy for companies to use these safety zones to fix wages and prices.

It’s an open question as to how much this algorithmic price-fixing software could be contributing to inflation, but as the Kansas City Fed noted in January, “markups could account for more than half of 2021 inflation.” Mekki admitted as much on Feb. 2 at an antitrust conference in Miami:

An overly formalistic approach to information exchange risks permitting – or even endorsing – frameworks that may lead to higher prices, suppressed wages, or stifled innovation. A softening of competition through tacit coordination, facilitated by information sharing, distorts free market competition in the process.

Notwithstanding the serious risks that are associated with unlawful information exchanges, some of the Division’s older guidance documents set out so-called “safety zones” for information exchanges – i.e. circumstances under which the Division would exercise its prosecutorial discretion not to challenge companies that exchanged competitively-sensitive information. The safety zones were written at a time when information was shared in manila envelopes and through fax machines. Today, data is shared, analyzed, and used in ways that would be unrecognizable decades ago. We must account for these changes as we consider how best to enforce the antitrust laws.

The effect could be swift as businesses try to avoid antitrust suits. From ArentFox Schiff LLP, a national law and lobbying firm:

The withdrawal of the safety zone and increased scrutiny of information exchanges signal that broader enforcement against information sharing is coming. Companies should consult with their antitrust counsel to re-evaluate their current information-sharing practices.

The DOJ will have to make sure penalties are steep in order to prevent information sharing from becoming just another “cost of doing business.” It will also be tough for the antitrust division to take on too many cases. The fact that APHIS had to rely on AGri Stats for data and that it took the DOJ so long to go after Agri Stats are more signs of the hollowed out US government. The DOJ is woefully underfunded and understaffed for what it’s up against (and that’s if its attorneys have any actual interest in enforcing antitrust as opposed to simply deciding which revolving door is the most appealing).

To quote: “In 1993, first lady Hillary Rodham Clinton and other officials announced steps to make healthcare more “available” and “affordable” to all Americans. The policy statements provided for antitrust “safety zones” which created circumstances under which the DOJ and the FTC would not challenge exchanges of price and cost information”

Gosh golly, where have I heard that name before, Hillary Rodham Clinton? I’ll have to do some searching on the WWW. I may find that Bill Clinton was at the White House back then and had something to do with this arrangement, too.

Like Dick Cheney, Hillary Clinton has a career that consists of being wrong about everything.

As we see here, one must loot the village to raise its idiot.

It’s unfortunate indeed that all of this creative destruction by supposedly rational actors somehow engaged in criminality doesn’t conform to the scriptures handed down by Milton Friedman and Gary Becker, whose shades are now flitting about in Hades. Here on Earth, I’m getting a strong whiff of fraud.

Anti-trust safety zone, another bafflegab oxymoron entry for the lexicon. The ends can always justify the means with more persistence and the occasional bribery and shouting.

All it took was a crook from Arkansas to turn “Reaganomics” into “Rubinomics” and to codify the felt “pain” used to unite the Democrats under a feigned, saxophone-playing sympathy for the scummiest POTUS in my lifetime. Reagan proudly proclaimed the virtues of his scurrilous agenda. The Clintons hid behind a PR machine that destroyed FDR’s New Deal and pushed an already teetering Democratic party over the edge to a perdition from which the USA will never recover.

Never.

Hi, i have some experience in the food industry over here in Europe and I really (honestly!) cannot understand the logic behind this article.

First: at least here it is the retailers the party that does hold dominance when determining industrial food prices (better said: industrial profits). The supermarket chains regularly do strongarm the producers into lowering their prices and holding the producer´s profits in a very tight range (e.g. 5-10%), especially in products with short shelf life such as fresh produce or meat.

Second: how does sharing purchasing and processing costs substantially help meat packers to create some kind of cartel? I would say this is not necessary at all in order to agree some price fixing between them…

Would be very glad if other commenters could clarify a bit this topic!

The article does say at the beginning that price information is being shared, so that would allow the producers to monitor compliance with any “backroom” agreements on pricing.

This seems to be another example of how technology provides one-sided efficiency benefits by decreasing the cost of collusion.

Everything about the old Gilded Age is new again — including the “Trusts” and “Combines” of old.

This goes back a lot further than the Gilded Age.

“People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices.”

Adam Smith, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, 1776.

Yes, thanks, KLG. I hope the JD goes after AgriStats, but any high school kid with a computer and internet can go online and get nearly equivalent pricing information. Or just walk into a couple of supermarkets and pay attention to prices. The only way to put a lid on price fixing is to fix the Maximum Wage that the crooks at the top of these food chains are allowed to take home as a reward for their selfish behavior.

The only way that’s gonna happen is with another Great Depression. The West has made a good start on that. Unfortunately it’s going to cause a lot of pain and suffering to others before it repents.

How interesting to set a Maximum Wage. Because a corporation is “allowed” to be chartered, there must be underlying responsibilities. Do you know the basic rules of the road for a publicly chartered legal person aka corporation? That would be an interesting study–what is the implied social contract of a charter?

The airlines must have their own Agristats to share and post fares which seem to be the same across all airlines!

The old CAB*-regulated fixed-fare regime had its advantages. I remember being able to exchange unused tickets on one airline for tickets on any other airline, or for a credit voucher that could be redeemed on any airline.

* Civil Aeronautics Board

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Airline_Deregulation_Act

You can’t have efficient markets without price transparency. Commodity prices are available more or less constantly through the Chicago Board of Trade. Even the Red Chinese Communists have come to grips with global market prices.

US healthcare is not a rational market. Or a market at all.

People study this stuff endlessly.

Anyway, having price information isn’t close to price fixing. Markets set an upper bound on prices, and underlying cost sets a lower bound. Although firms have to make the extent to which they rely on variable or marginal costs verses total costs. Even with perfect information, firms have to decide on a pricing process, which tend to be complex.

Grains are below $10 bushel, or 40 cents a pound. So you cant say they aren’t brutally efficient.

Coke and Pepsi are a cartel of sorts, but you can but a 2 liter bottle in a convenience store for less than a bottle of water.

TPTB might look at the anti-competitive restrictions on supply of say, housing, medical care, etc. Or just shoot the messenger.