By Delphine Farmer, a professor of Chemistry, Colorado State University. Originally published at The Conversation.

When wildfire smoke turns the air brown and hazy, you might think about heading indoors with the windows closed, running an air purifier or even wearing a mask. These are all good strategies to reduce exposure to the particles in wildfire smoke, but smoky air is also filled with potentially harmful gases. Those gases can get into buildings and remain in the walls and floors for weeks.

Getting rid of these gases isn’t as simple as turning on an air purifier or opening a window on a clear day.

In a new study published in the journal Science Advances, colleagues and I tracked the life of these gases in a home exposed to wildfire smoke. We also found that the best way to get rid of the risk is among the simplest: start cleaning.

The Challenge of Smoke Particles and Gases

In December 2021, several of my friends and colleagues were affected by the Marshall Fire that burned about 1,000 homes in Boulder County, Colorado. The “lucky” ones, whose homes were still standing, asked me what they should do to clean their houses. I am an atmospheric and indoor chemist, so I started looking into the published research, but I found very few studies on what happens after a building is exposed to smoke.

What scientists did know was that smoke particles end up on indoor surfaces – floors, walls, ceilings. We knew that air filters could remove particles from the air. And colleagues and I were just beginning to understand that volatile organic compounds, which are traditionally thought to stay in the air, could actually stick to surfaces inside a home and build up reservoirs – invisible pools of organic molecules that can contribute to the air chemistry inside the house.

Volatile organic compounds, or VOCs, are compounds that easily become gases at room temperature. They include everything from limonene in lemons to benzene in gasoline. VOCs aren’t always hazardous to human health, but many VOCs in smoke are. I started to wonder whether the VOCs in wildfire smoke could also stick to the surfaces of a house.

Tracking Lingering Risks in a Test House

I worked with researchers from across the U.S. and Canada to explore this problem during the Chemical Assessment of Surfaces and Air, or CASA, study in 2022. We built on HOMEChem, a previous study in which we looked at how cooking, cleaning and occupancy could change indoor air.

In CASA, we studied what happens when pollutants and chemicals get inside our homes – pesticides, smog and even wood smoke.

Using a cocktail smoker and wood chips, we created a surprisingly chemically accurate proxy for wildfire smoke and released small doses into a test house built by the National Institute of Standards and Technology. NIST’s house allowed us to conduct controlled chemistry experiments in a real-world setting.

We even aged the smoke in a large bag with ozone to simulate what happens when smoke travels long distances, like the smoke from Canadian wildfires that moved into the U.S. in the summer of 2023. Smoke chemistry changes as it travels: Particles become more oxidized and brown, while VOCs break down and the smoke loses its distinctive smell.

How VOCs Behave in Your Home

What we found in CASA was intriguing. While smoke particles quickly settled on indoor surfaces, VOCs were more insidious.

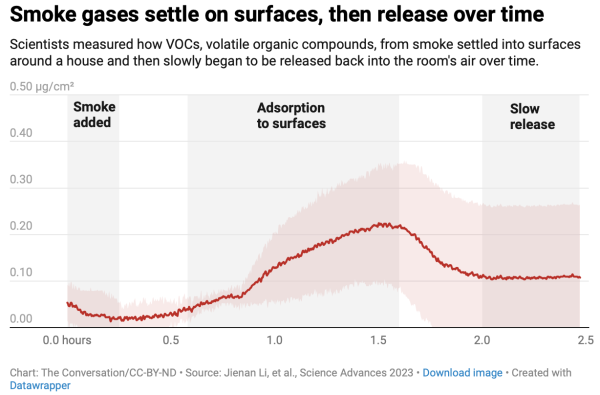

At first, the house took up these smoke VOCs – on floors, walls and building surfaces. But once the initial smoke cleared, the house would slowly release those VOCs back out over the next hours, days or even months, depending on the type of VOC.

This release is what we call a partitioning process: During the smoke event, individual VOC molecules in the air attach to indoor surfaces with weak chemical bonds. The process is called adsorption. As smoke clears and the air cleans out, the bonds can break, and molecules “desorb” back out into the air.

We could watch this partitioning happen in the air by measuring smoke VOC concentrations. On surfaces, we could measure the weight of smoke VOCs that deposited on very sensitive balances and then were slowly released.

Overall, we concluded that this surface reservoir allows smoke VOCs to linger indoors, meaning that people are exposed to them not just during the major smoke event but also long after.

Why Worry about VOCs?

Smoke VOCs include well-known carcinogens, and high levels of exposure can induce respiratory and health problems.

While smoke VOC concentrations in our test house decreased with time, they remained persistently elevated above normal levels.

Given that VOC concentrations from other sources, such as cooking and cleaning, can already be high enough in homes to harm health, this additional long-term exposure source from smoke could be important. Further toxicology studies will be needed to determine the significance of its health effects.

How to Clean Up When Smoke Gets In

So, what can you do to remove these lingering smoke gases?

We found that air purifiers can remove only some of the VOCs that are in the air – they can’t clean the VOCs on your floors or in your walls. They also work only when they’re running, and even then, air purifiers don’t work particularly well to reduce VOCs.

Opening windows to ventilate will clean the air, if it isn’t smoggy or smoky outside. But as soon as we closed windows and doors, smoke VOCs started to bleed off the surface reservoirs and into the air again, resulting in an elevated, near-constant concentration.

We realized that to permanently remove those smoke VOCs, we had to physically remove them from surfaces.The good news is that cleaning surfaces by vacuuming, dusting and mopping with a commercial, nonbleach solution did the trick. While some remediation companies may do this surface cleaning for you after extreme exposures, surface cleaning after any smoke event – like Canadian wildfire smoke drifting into homes in 2023 – should effectively and permanently reduced smoke VOC levels indoors.

Of course, we could reach only a certain number of surfaces – it’s hard to vacuum the ceiling! That meant that surface cleaning improved but didn’t eliminate smoke VOC levels in the house. But our study at least provides a path forward for cleaning indoor spaces affected by air pollutants, whether from wildfires, chemical spills or other events.

With wildfires becoming more frequent, surface cleaning can be an easy, cheap and effective way to improve indoor air quality.

When I first read this all I could think was “WASH YOUR HANDS!”, but as a transport phenomena enthusiast I can see there point. The main driver of transport, in this case diffusion, is concentration gradient. The article says that you can open windows to reduce the VOC concentration, but when you close the windows you see an uptick in concentration. This is due to the concentration gradient from the adsorbed surface to the relatively pure air. Tesla in China had a novel solution to a similar problem with the plasticizers in their new cars, that new car smell to Mericans. Tesla had a program that would turn on the heaters in the car and jack up the temperature, to increase the “carrying capacity” of the air, and then open the windows to remove the plasticizer from the system.

That ‘new car smell’ has been around a lot longer than there have been (so many) plastics, or plasticizers [?], in automobiles. I was once told that it comes from the formaldehyde used in making the upholstery.

I hate new car smell! When I bought my car I asked the dealership to leave it outside during the day with the windows down for a few days before I picked it up. They thought I was nuts. Really, it isn’t just the health problems for me, it is that awful smell.

So many products have that good chemical smell – IKEA furniture, yuck. We once bought a foam topper for an older mattress, we aired it out for days outside and the smell was no less, ended up returning it. I am currently shopping for carpet (for many reasons tile or hardwood won’t work). You can get low VOC carpets but no one will guarantee me that they won’t smell. Leaning towards wool, but, my oh my, it will blow the renovation budget!

The thought occurred to me that in olden days people would open up all their windows and perhaps wash the interior of their homes to clean out the remnants of this smoke. But these days lots of homes are built with only small windows as any cooling or heating is being done by an air-conditioner by design. So it would be interesting to see if those air-conditioners get rid of this residual smoke or just recirculate it around the rooms in those homes.

Air conditioners and heat furnaces (using the same ducts) have filters, perhaps there are adequate filters for forest smoke residue. But should the ducts be cleaned from inside? In old days, chimney sweepers were employed.

During the 2007 Buckweed fire, my parents home and property were mildly damaged by the fire and the surrounding countryside was black. They had the keep the house closed up because the burnt smoky smell was worse outside than inside. My mother cleaned, they ran the AC and changed the filters frequently + ran extra hepa air purifiers, but the smell inside the house persisted. The insurance adjuster gave her a tip that worked like a charm within a week. This was cheap and non-toxic. He said to place 2 cut up apples in a bowl in each room. Replace them every couple of days until the smell is gone. I’m guessing they absorbed the chemicals releasing from the surfaces that the article is talking about. Worked!

More expensive than apples but another great absorber is ground coffee. My mother-in-law was a very heavy smoker. She had some very nice furniture and when she died we had trouble selling or even giving it away because of the smell. We steam cleaned all the upholstered furniture, cleaned all the hard surfaces with Simple Green and on a neighbours’s advice put ground coffee in all the drawers and nooks. It worked really well. The high end consignment shop that turned up their noses at first ended up taking and selling everything for us.

Ps – Thanks for this info Conor, as Lambert says – news you can use!

The apples may give off ethylene gas that has an effect on adsorbed VOCs.

It’s not hard to vacuum the ceiling! Have these people never cleaned the tops of their door jambs or light fixtures?

What’s hard is replacing a dang popcorn ceiling.

Truth, popcorn (low levels of asbestos, sometimes) is awful to remove unless you get down to the drywall.