A reason to pay a bit of attention to the Wall Street Journal’s Greg Ip joining the ranks of “China still could wind up in a world of hurt” prognosticators is that Ip has long been a Fed whisperer. That does not mean Ip is retailing central bank views in his new piece, Don’t Rule Out a Financial Crisis in China. But it does mean his reading has likely been influenced by conversations with Fed economists.

Needless to say, Ip’s views are conventional if carefully argued. As we’ll indicate, he also misses a couple of key issues stressed by China optimists. However, consistent with the title, Ip is flagging that China’s economy is unbalanced and therefore subject to crash risk, as opposed to making a call.

The world’s second largest economy has a deflating property bubble, local governments struggling to pay their debts and a banking system heavily exposed to both.

Anywhere else these factors would be seen as precursors of a financial crisis. But not in China, conventional wisdom goes, because its debts are owed to domestic rather than foreign investors, the government already stands behind much of the financial system and capable technocrats are on top of things.

Conventional wisdom might be dangerously out of date.

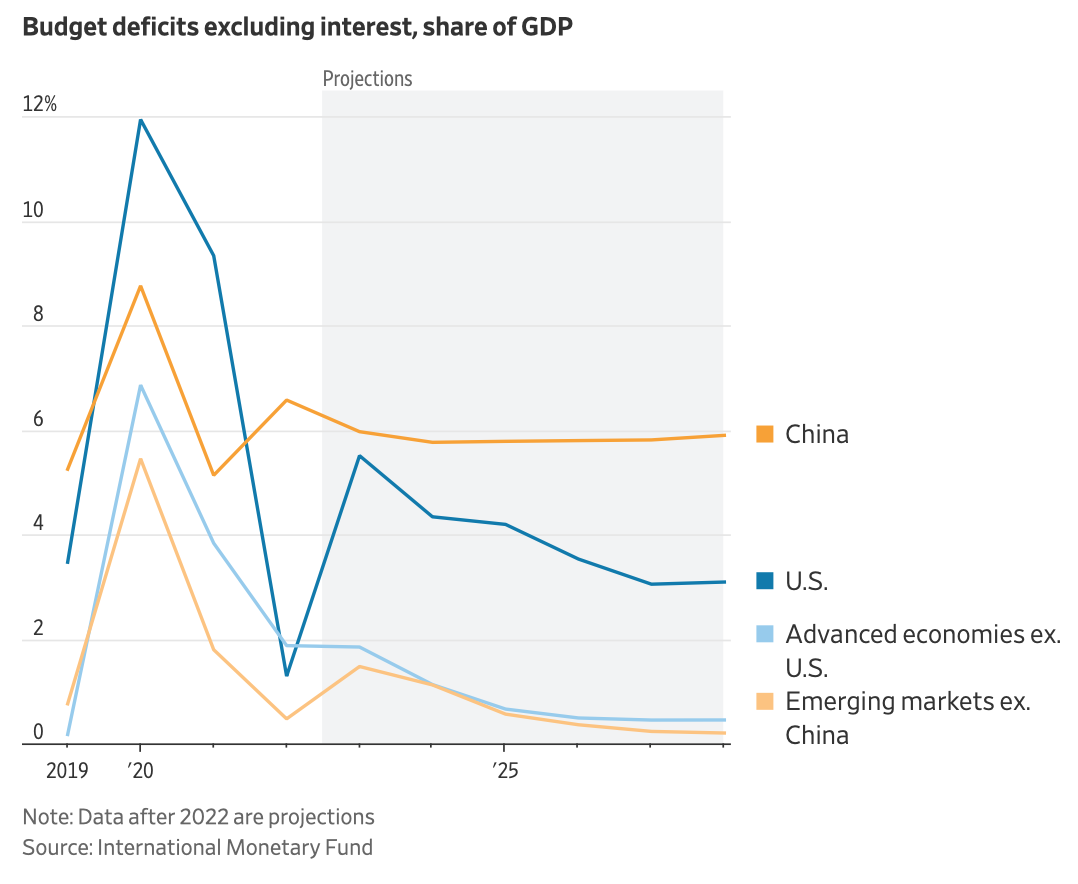

Ip then turns to fresh IMF data, noting that even though China slightly beat growth expectations through the 3rd quarter with results of 4.9%, the international agency lowered its forecast for China to 4% over the next for years. That’s a cut from its year-ago estimate of 4.6% for that four-year projection. Note this decelerating growth, which is not great by China standards, comes despite sustained and high fiscal stimulus:

Ip then takes a neoliberal view, warning of China’s debt to GDP ratio, projected to rise to 149% of GDP by 2027, if local government debt (45% of GDP) were included. The local government and private debt are what bear watching. The Chinese government, like ours, can always “net spend,” as in run deficits, whether nominally financed by bonds or not. That risks creating too much inflation, not default risk.

The reason for respectable if not impressive growth results despite a seriously deflating housing sector is that government spending into sectors like green energy. Consumer spending also increased. Some see the 4th quarter as accelerating, but that does not necessarily contradict the IMF view about the medium term:

'China: Just-fine growth allows prudent policy' sees 5.6% GDP growth in Q4 following 4.9% Q3 upside surprise; consumption, infrastructure spending and real estate contributed to Q3 outcome while infrastructure to be main source of Q4 gains: https://t.co/aWD9d8FHry pic.twitter.com/56qvkPWtuZ

— Medley Advisors (@medleyadvisors) October 18, 2023

Michael Pettis, who also weighed in on the 3Q performance, was cautionary about longer-term outcomes:

5/9

And that surge has been substantial. At the beginning of this year I wrote that after the terrible 10 percentage point increase in China's debt-to-GDP ratio in 2022, I expected a much lower increase in 2023, perhaps of 2-4 percentage points.— Michael Pettis (@michaelxpettis) October 18, 2023

7/9

This increase in debt, remember, is supposed to lead to a nominal increase in GDP of about 5-6 percent. That’s an awful lot of debt for so little growth. That is why I argue that the extent of high-quality growth matters far more than the extent of GDP growth.— Michael Pettis (@michaelxpettis) October 18, 2023

Even though Pettis IMHO similarly falls for the neoliberal fixation on government debt to GDP, not distinguishing whether the government in question is a currency issuer or user, he nevertheless makes an important and often neglected point about the productivity of government spending. It’s one thing if a substantial amount is going into activities that will increase productivity in the future, like education, health care, and improved energy efficiency. It’s another when, say as in the US, it goes to things like military pork and pharma grifting, rentier activities that come at the expense not just of growth but even lifespans.

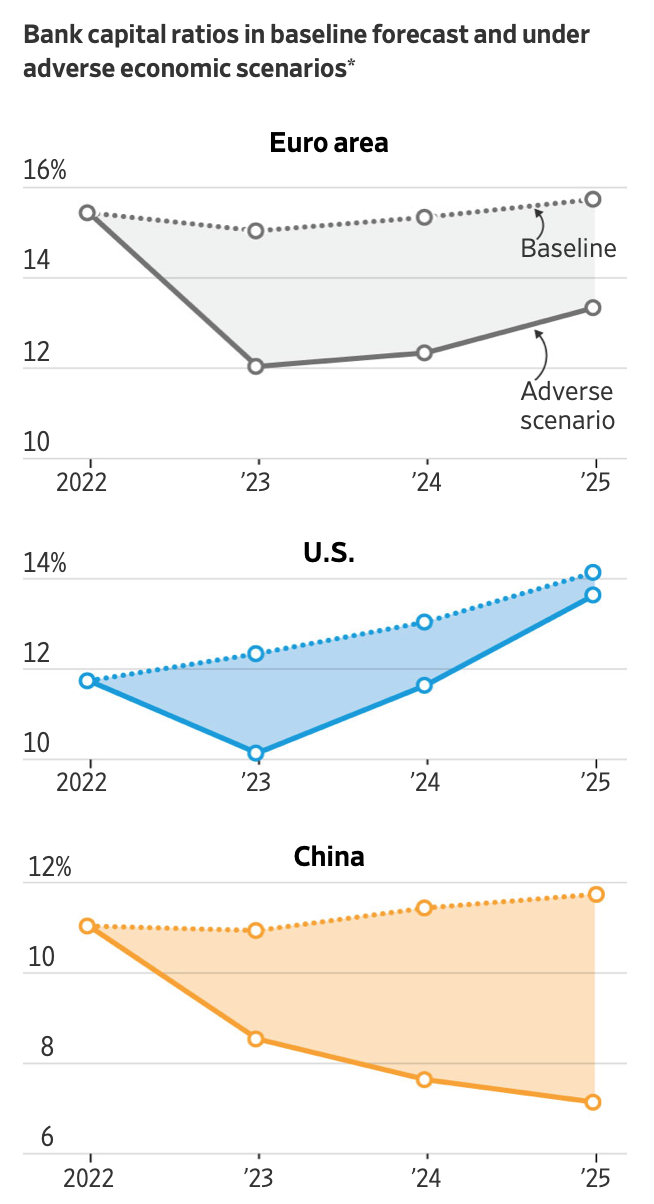

IP includes another IMF chart, showing bank Tier 1 capital projections:

He points out that Chinese banks are not exposed to typical flight risk:

Chinese banks are also mostly owned or controlled by the central or local governments that would presumably not let them fail, precluding bank runs and panics. In China’s last bout of banking trouble 20 years ago, bad loans were transferred at par value to state asset-management companies.

But sometimes financial crises occur because local, not foreign, investors flee. Nor are they always fast and violent, like the global financial crisis from 2007 to 2009. Some unfold over years as occurred in Spain in the 1970s, the U.S. (with its savings-and-loan institutions) in the 1980s, and Sweden and Japan in the 1990s.

But as Pwttis pointed out (and the state of search means I can’t find his precise formulation), the Chinese approach to that crisis had the effect of making the economy even more imbalanced, by putting the cost of the bank crisis on consumers, among other things via financial repression. That led consumers to save even more and spend less as their earnings on safe investments greatly lagged inflation. China needs the reverse, to move to a more consumption-led economy. Every large economy that has made that transition has experienced a financial crisis. China keeps deferring that crisis by not making that transition. But how long can it keep it up?

9/9

But until there is a real transfer of income to households that boosts domestic consumption sustainably, and a declining reliance on surging debt to keep the numbers growing, China's structural problems are unchanged.— Michael Pettis (@michaelxpettis) October 18, 2023

So again, China has kept its unbalanced model functioning. Will intensified political stress play out in ways that lead to bigger China wobbles? We are set to find out, like it or not.

Just a point about Pettis’s view on debt – he has in the past written quite favorably about MMT, I think its fair to describe him as an MMT lite economist (or as far as one can be without losing your mainstream academic cred), so he is well aware that government debt denominated in a fiat currency is nowhere near as important or dangerous as other forms of debt. He does, however, believe that there is only limited scope to monetize the debt away in China, although I confess to not fully understanding his reasoning. While I like his analyses and think he is broadly correct, he has been wrong in the past in his predictions about the impact of debt on the Euro.

I think a China economic crisis is unlikely, for all the reasons outlined above and elsewhere. A medium to long term Japanese style stagnation along with deflation is a far more likely risk for China if it insists on repeating the same policies over and over again. However, I suspect that if a crisis does arise, it will be in local government financing. Its hard to exaggerate just how important the various levels of local government are in China in driving local economies, and how dependent they are on property values for financing these works, and how interrelated the networks of local government, banking and business is within most regions. I suspect that nobody really knows how much debt is lurking on balance sheets and who really owns it. The reality is now that local governments have been told to increase spending rapidly while their source of funding is disintegrating, more or less permanently. At some stage there will be a crunch, and Beijing will have to step in. The problem seems to be political rather than economic – for reasons beyond my limited knowledge there seems to be a very deep reluctance by Beijing to bail out any local public debts – probably because they see this as ultimately pulling a thread with no known ending. My guess is that they believe that if they try to bail out local governments a lot of previously ‘private’ debt will somehow or other end up on a public balance sheet.

None of China’s problems are permanent or incurable – many of the solutions are pretty obvious (like giving everyone a raise, creating a proper local tax base and investing more in social protections). But the networks of power and influence in China are very opaque and its not certain at all that even if Beijing understands what needs doing, it has the political or administrative capacity to do it.

Is mass consumerism actually a more balanced economy? as suggested by Pettis – “consumption-led economy” –

I for one, don’t think so – at least not in the form of got-to-have-the-latest-model of some planned-obsolescent crappified widget

Yes it is. You can’t keep exporting and investing enough to support goaf as an economy gets bigger. Witness the housing bust in China.

I think the investment type is important – investment in pre-existing assets to make those assets worth more is mal-investment of financial capital at the expense of citizens (known officially as consumers) who can not eat financial capital but must eat the products of industrial capital and buy or rent housing (real capital) that is in balance with the tangible economy. A housing bust is termed a bust because the financial value of property suddenly goes down – I think…. so that a bust in the Chinese market would actually be a positive in that housing would become more affordable to a larger group who then would have more left over for more consumption to lead the economy towards balance. At least it would lower the cost of living which would lower the demand for higher wages which would would be an advantage on global market competitiveness. In the USA – we have goosed the prices of so many asset classes through financial speculation that the cost of living has accelerated past the income needed to live — and have priced us out of real goods global markets. I guess I am trying to say that the cost of living going up is due to financial speculation and renterism that is not tied to production-and-consumption economy.

owning their homes at the same cost they would have had to pay in rent – the economic definition of equilibrium in property prices.

Sorry, China has massively over-invested and not just in real estate. China has cement capacity of 3.5 billion tons v. global consumption of 4.4 billion. There were reports years back of excess capacity in various types of high end manufacturing. You cannot keep investing on China’s scale and not have a lot wind up being unproductive. Japan did bridges and roads to nowhere in the early 1990s. China’s overinvestment in real estate is an echo of that.

“…China needs the reverse, to move to a more consumption-led economy. Every large economy that has made that transition has experienced a financial crisis. China keeps deferring that crisis by not making that transition…”

Does the Chinese government really want to make that transition or do others want that for them? Are there competing sides within their establishment about the idea?

Yes, there has long been arguments/discussions within China (or at least, public statements that we know of) about the direction and purpose of China’s growth policy, and there have been for decades – especially in the context of the Japanese collapse in the late 1990’s which was intensively studied by the Chinese government and has long been their fear.

The main arguments are about how long they can maintain a policy of focusing on internal infrastructure investment and exports as the main driver of growth over domestic consumption. Plenty of analysts inside and outside China are arguing that there is still scope for further capital investment (albeit with shrinking returns), but obviously there is a limit to how long you can maintain an export led economy before you run out of countries willing to buy your surpluses, and likewise there is a limit to how many factories and railways and houses you can build before it becomes self defeating (i.e. the costs of overbuilding reduce, rather than increase productivity).

In the end, its a banal insight that if you can’t export any more products, and you’ve run out of anything left to build that needs building, the only source of growth can be internal demand (ok, there is also military spending, but thats another topic). So its either that, or abandon growth in favour of redistribution, which is of course another possibility, albeit one that nobody wants to talk about.

Thank you. There seems to be an urgency among some economists for China to rush into a decision.

I thought the last sentence of Mikel’s comment got to the heart of the issue. After all, if reading NC has taught me anything, it’s that economic power goes hand in hand with political power. Which is to say, perhaps the “financial crises” experienced by other countries that transitioned to a consumption-led economy should instead be seen as a political one and each delay in making that transition a political victory for Chinese property developers and their allies, and a defeat by those few who would most benefit from the change.

Perhaps changing rates of employment in different sectors of the economy among the CPC princes and princesses are a better predictor than debt ratios etc?

That’s a very complex subject, and one beyond my knowledge of China – probably one beyond any agreement among experts, Chinese or otherwise.

As has been often described and analysed by development economists/geographers, there is a fundamental problem in rapid catch up growth, in that the policies needed to promote rapid growth are not the same as those needed to mature as an economy. And there is a paradox in that the success of a rapid catch up model builds up strong forces within the country which can make the transition very difficult. As one obvious example, if you’ve built up a range of companies which specialize in exports, they will resist the policies needed to build up your internal economy such as a stronger currency, higher wages, more social spending. There is plenty of evidence that this is a significant factor in China right now just as it has been in the Asian Tiger economies or countries like Germany. I think its very significant that the current Beijing policy is to push even more investment into railways, ports and factories despite clear evidence of existing overcapacity. This is good news for the rest of the world (even more cheap solar panels, cars, batteries, etc. flooding markets), but its doubtful whether its a sustainable policy for China.

But as you suggest, there are also the social problem of having created a range of very wealthy people who like things as they are. There are lots of anecdotes – many I’ve heard personally from Chinese friends – of a new elite – a Chinese PMC if you like – who are closing the door to those coming up behind them. Its not just elite princelings (who have long been loathed by most Chinese) who you will see at play all over the world – on a more mundane level just getting a job in any big company is now increasingly difficult if you don’t have a well connected relative. My closest Chinese friend had to pay a very large sum of money last year just to ensure her engineer nephew didn’t lose his new job to someone less qualified but more able to pull the right strings. And this was just for a standard starting job for a new engineer in a city metro.

One thing I haven’t seen yet, but maybe it will come, is what the Korean-British economist Ha Joon Chang has written about in labour markets, whereby the best and brightest migrate from ‘productive’ sectors like engineering into sectors like medicine and law, which seem to offer a more guaranteed entry to the upper middle classes. He sees this as characteristic of countries which have lost their way economically. I suppose its a variation of the theory of elite overproduction, whereby the upper middle classes create niches for their offspring to protect their status, often at the expense of the overall economy. For now, China is still very good at pushing its smartest kids into productive sectors, although whether it can keep creating jobs for them is another matter.

I think a useful metric for comparing national economies would one be that measures the extent to

which the each country’s PTB, especially its government, puts a value on maintenance of the wealth of its wealthiest members and, consequently, of the wealth and income disparities that result.

I do not expect to see such a measure appearing in any econ text books soon.

This “crisis” never made sense to me. Americans are obsessed with investment forgetting primary purpose of housing sector. Rentier classes living from investments are actually burden to society, it is not a bad thing when they lose money.

Some time ago I ran across an article on China’s poverty-alleviation process. CPC cadre are sent out to live in the impoverished villages, find out who is impoverished and why, and to engineer solutions and educate the local population. They’re coordinators and facilitators. Interestingly, these rarely involve money from Beijing. Often they take the form of infrastructure obtained by partnerships with wealthier towns or companies donating material, setting up new branches to provide employment, etc. It’s highly cooperative and focused on increasing the productivity of the whole area. The participation of companies was especially interesting. China is fostering a ‘corporate responsibility’ model that you don’t see anywhere else in any great degree. They need to be deeply connected to the community and socially useful not only to exist but to thrive there.

Where there is disability, etc. They will hook people up with government-supplied funding, but they also find ways for them to be productive and to be able to improve their own condition at the same time (instead of, as in the US, punishing such attempts by cutting them off.)

This sort of widespread local initiative undoubtedly makes it more difficult for outsiders to assess and predict the larger effects on the economy, though. Perhaps local debt is less of a problem than it appears to the ordinary cutthroat-capitalist economist. ;)

Beijing has pretty much eradicated rural Chinese subsistence poverty.

Makes the West’s decades-long effort in the developing world look pathetic.

I agree with Pettis on China’s rebalancing in the sense that as long has the country relies on a large trade surplus, it is exposed to risks from loss of trade. The direct solution is to pay workers more so there is more internal demand and more balanced trade.

I find the chart on budget deficits excluding interest to be problematic. Why exclude interest on debt? Isn’t it a budget item that takes resources from other areas? How did the US numbers drop so fast when the country ran a $2.5 trillion deficit in FY22 – net of interest expense is about $1.8 trillion or 7% of GDP. Meanwhile the chart shows less than 2%. My guess is that interest is excluded to make China look worse and the US look better. Imagine if interest rates stay and the US has $1 trillion in interest expense in FY24? Budget deficit less interest will surely go down – but the pressure on the economy will be the opposite.

The purpose of exports is to earn foreign currency that can be used for buying imports. You can’t replace exports with domestic consumption.

One reason a country could be export driven is because it does not generate enough internal demand. Paying people more, without raising prices, means that they can buy more domestic goods and imports – either way net exports drop.

Remember we are talking about the world’s largest exporting economy, they are not lacking in foreign currency.