Yves here. Wolf Richter provides some important sightings confirming that there’s plenty of liquidity in the financial system, which is at odds with what the Fed has been trying to achieve with its rapid interest rate increases and its intention not to back off until it sees results. We said from the get-go that the Fed was unlikely to be able to whip inflation via interest rates increases, short of killing the economy stone cold dead, since many of forces driving this inflation were the result of supply factors that interest rates cannot address.

But Wolf’s factoids suggest that the Fed tightening is failing even in its own terms, of trying to dry up credit to dampen down business activity and above all, wages. Why might that be?

Looking at money supply is a poor metric. Monetarist experiments in the US and UK in the early 1980s established that changing money supply levels correlated with no significant macroeconomic variable, even on a lagged basis. A big reason, if you believe in that framework, is that prices are supposedly a function of monetary velocity as well as supply. What might be increasing monetary velocity? Various forms of shadow banking, ranging from the rise of private credit funds, as opposed to banks, as suppliers of funds. Another is the use of derivatives to increase leverage, witness the Fed-approved bank use of synthetic risk transfers, which allow banks to blunt the effect of tighter capital requirements.

In the runup to the 2008 crisis, some analysts and reporters (including yours truly) took note of and tried to understand the so-called “wall of liquidity” which resulted in pervasive underpricing of credit risk. That’s finance-speak were “lenders not demanding high enough interest rates to compensate for the risks they were taking.” The culprit then was structures and strategies that created leverage on leverage, particularly asset-backed CDOs and credit default swaps. One leverage on leverage strategy operating now is private equity subscription credit lines, where private equity firms borrow against unused limited partner capital commitments rather than simply use that source of funding. But it is well nigh impossible to get good data on the use and impact of this approach.

Readers who have intel on subscription credit lines and other leverage on leverage strategies are very much encouraged to speak up in comments.

By Wolf Richter, editor of Wolf Street. Originally published at Wolf Street

One of the big surprises this year is that the Fed’s 5.5% policy rates and $1.1 trillion in QT have neither meaningfully tightened financial conditions nor slowed the economy.

The Fed has been “tightening” since early 2022 in order to “tighten” the financial conditions, and these tighter financial conditions are then supposed to make it harder and more expensive to borrow which is supposed to slow economic growth and remove the fuel that drives inflation. “Financial conditions,” which are tracked by various indices, got a little less loose, and then they re-loosened all over again. It’s almost funny.

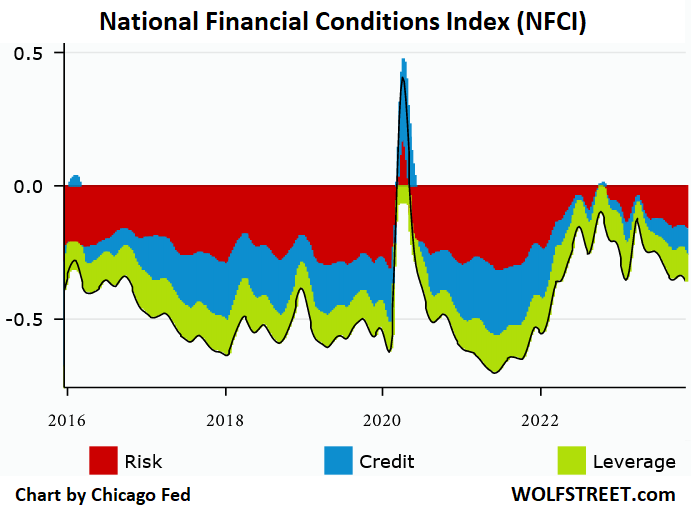

The Chicago Fed’s National Financial Conditions Index (NFCI) loosened further, dipping to -0.36 in the latest reporting week, the loosest since May 2022, when the Fed just started its tightening cycle. The index is constructed to have an average value of zero going back to 1971. Negative values show that financial conditions are looser than average, and they have been loosening since April 2023, after a brief tightening episode during the bank panic (chart via Chicago Fed):

You can see in the chart above how financial conditions tightened in March 2020, but not for long – by May 2020, as the Fed was dousing the land with trillions in QE, they were already loose again.

So, despite the rate hikes and QT by the Fed, financial conditions are as loose as they were when the Fed had just started tightening in May 2022, and they are far looser than the long-term average, though they have become somewhat less loosey-goosey than during the free-money era starting in mid-2020 through early 2022.

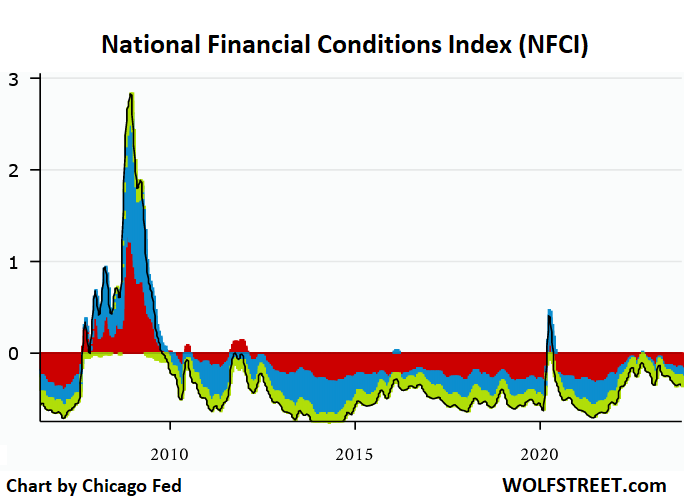

The long-term chart below of the NFCI shows what happens when financial conditions tighten so much that they strangle the economy, as they did during the Financial Crisis. The March-2020 spike barely registers in comparison.

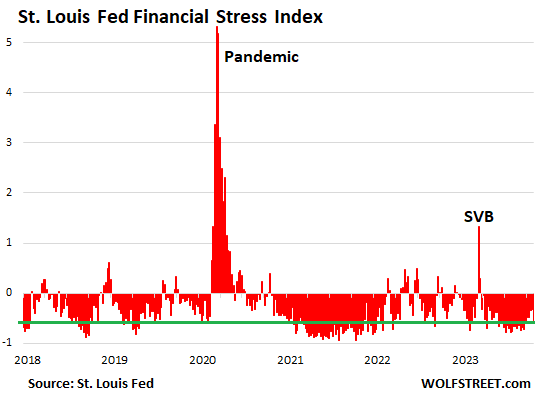

The St. Louis Fed’s Financial Stress Index takes a similar approach and measures financial stress in the credit markets. The zero line denotes average financial stress. Negative values denote less than average financial stress. In the current week, it dropped to -0.56. The green line shows this current value across time and denotes that credit markets are still in la-la-land.

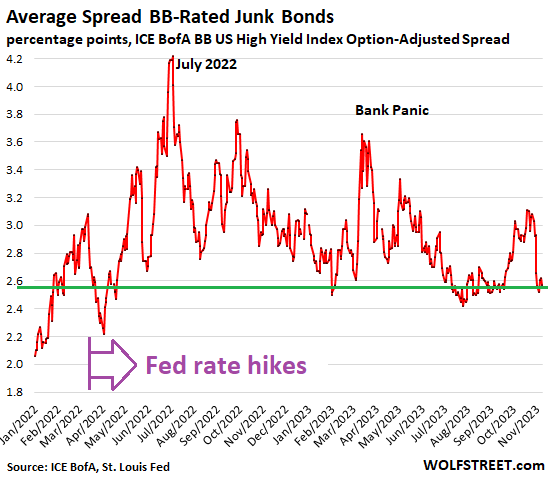

The BB-rated junk-bond spreads are another measure of financial conditions. Corporate bond yields should rise or fall with Treasury yields. But a wider spread between those corporate bond yields and Treasury yields indicates tighter financial conditions; a narrower spread indicates looser financial conditions.

The average spread of BB-rated bonds, the less risky end of high-yield (my cheat sheet for corporate bond rating scales) narrowed further yesterday to 2.57 percentage points. So this is going in the wrong direction, in terms of what the Fed wants to accomplish.

Sure, some sectors are stressed and financial conditions tightened in those sectors, such as the office sector of commercial real estate, but the troubles in the office sector have structural causes, including working from home and the corporate realization that they don’t need all this vacant office space that they have been hogging for years, and will never grow into.

And home sales have plunged because potential sellers don’t want to give up the 40% to 60% price spike they got over the period of pandemic QE; and buyers just laugh at those prices and go blow their down-payment on all kinds of stuff and services, including travels and cars – new vehicle sales surged 20% year-over-year in Q3 – contributing to consumer spending.

And sure, the major stock indices are down from their highs a couple of years ago. Sharply higher yields (lower bond prices) have put pressure on bank balance sheets, and a few, run by goofballs that failed to manage this properly, have collapsed.

But consumers are working in record numbers and are making record amounts of money, after receiving the biggest pay increases in 40 years that in 2023 are finally outrunning inflation, and they’re spending huge amounts of money and are still able to save some. We’ve been lovingly and facetiously calling them our Drunken Sailors here since at least March.

And companies, flush with cash from selling a tsunami of bonds at low rates during the Fed’s 0% era, are investing, including in a huge construction boom of factories. And they’ve raised their prices, because, you know, this is inflation, and they got away with it.

And the true Drunken Sailors, the folks in Congress, are throwing trillions of dollars a year in still easily borrowed money at the economy to fuel growth and inflation.

So the Fed’s policy rates that went from 0.25% to 5.5%, and its $1.1 trillion in QT so far have failed to broadly tighten financial conditions and slow down this train.

Could it be... that so much central bank liquidity was created during and before the pandemic that financial conditions cannot meaningfully tighten, despite the Fed’s tightening, until this liquidity gets burned up?

The Fed alone, not counting other central banks, created $4.8 trillion within two years of giga-money-printing, as Musk would say; it has now removed $1.1 trillion of it via QT.

Could it be, with so much liquidity still out there, that it might take a lot more and a lot longer to tighten financial conditions enough to where they have even a chance of removing the fuel from inflation?

And that’s kind of funny because if financial conditions don’t tighten enough to slow the economy and remove inflationary fuel, and if it then turns out that this dip in year-over-year inflation rates was just a “head fake,” to then resurge again, as Powell said he suspects it might, the Fed will go at it with more rate hikes. Powell made that clear. With credit markets still blowing off the Fed, are they trying to make sure that “higher for longer” gets entrenched? That would be funny.

I’ve been saying this years (the title of this article) that the Fed needs to sell off ALL it’s QE NOW – just to bring back normal. And what about stealth QE happening all time via monetary essissions like bailing out Silicon Valley banks which is QE for The Especially Rich? And yes, it may not be possible for the Fed to sell off its assets close to what it paid for. So that might imply other measures are needed like huge tax increases on the rich and Financial Sector. Interest rates are normal-ish, so let’s not throw away that improvement.

Small detail Timbers, QE has always been for the Especially Rich. I didn’t see credit card rates come down with QE. The poor depend on credit card borrowing to help pay their bills.

I hate to seem cranky but you say, apparently in all seriousness:

Talk about fire sale prices and profits for the rich. You clearly understand the implications of this:

Why create conditions that will absolutely kill the economy with an interest rate spike, and enrich the wealthy even more with essentially trillions in bond give-aways? Your proposed “solution” is:

This “solution” would only be adopted as a political expedient after the deep recession or depression this strategy would unleash. And even then I doubt it.

I sympathize with your aim, but the cure you propose is worse than the disease.,

….And home sales have plunged because potential sellers don’t want to give up the 40% to 60% price spike t….

The home market is frozen because sellers have to give up their 3% to 6%, 30-yr. mortgage. The appreciation doesn’t make up for the 8% mortgage on the housing ladder.

Homes sales are only liquid for retirees wanting to downsize, or first-time buyers who can get help from their the assets of their parents.

Last Thanksgiving, my cousin’s husband quipped that his family can never move from their just-moved-into house. The numbers will never work out again, particularly as their union-contract has not kept up with the 2020 to 2023 inflation.

And to me it’s gob-smacking (but not surprising as it’s a very-high-local-tax area, no more blood in the stones) as the area municipal-teachers contracts are being renewed, the workers are not finalizing contracts that put them into the same position as 2019 monetarily—they are not getting the >25% pay hikes that UPS/Teamsters and UAW got

People sell because they have to, buyers buy because they want to.

And yes at the current costs it makes no sense to move if they bought at the right time. Until the overall affordability changes, which means housing prices ces have to go down or stagnate. Which is what is happening nationwide.

Only those sellers who have lost their incomes will feel the imperative to sell NOW. The Fed is trying mightily to increase their numbers. This is another way the banks and the CDO mortgage bundlers make obscene profits every business cycle: buy housing low, bundle, then sell high when the market recovers.

All the other sellers can and will hold back, enjoy the roof over their heads, and ride out the cycle (disproportionately the PMC). They’ll rent their homes out if they need to. When the PMC starts getting pink slips in large numbers, the Fed will know the end of the hiking cycle has arrived.

False. Divorce. Estate sales. Elderly needing to move into assisted or a nursing home. Someone who’s gotten a job in another city. Loss of income so owner can no longer afford current house.

We had a house down the street go on the market just before I was about to list my mother’s house. They had bought that house to live in while they were doing a huge reno of another house, and put the neighboring house on the market when their big house was ready.

If someone sells a home at an inflated price why would they then need to borrow money to buy another home? Pay cash for the next home. Lots of Boomers are good candidates for downsizing – selling the big suburban house and then either renting or purchasing a smaller place. They would not need to borrow any money to purchase a smaller place. Why is this not happening?

It is happening. They snap up many of the good smaller home listings. There has been price inflation like the Austin example where Californians moving/downsizing to lower cost areas, with fat equity to transfer, have created so much demand that prices increased, only now with new supply are they starting to trend down in Austin, but still high elsewhere.

There is a severe shortage of listings in the ‘affordable’ range because oldsters, flippers, and young families are all competing for these, while so many owners are sitting tight because they don’t want a new mortgage at 8%. Meanwhile the builders only want to build apartment complexes and luxury subdivisions.

My mother is selling her home right now and has lots of interest (no pun intended) because her 2.2% mortgage is assumable. Selling a house has circled back to 1977 but with inflated base prices.

The Federal Reserve Board’s performance in all manner of things, like bank regulation, monetary affairs, 100 cents on the dollar for AIG’s CDS, failure to discipline the market when the market had its taper tantrum (I mean the list just goes on and on and on…), has been subpar for quite a number of years. I hope the Board’s subpar performance becomes subject to a long-term, consistent cascade of criticism from right and left. I mean, there are just so many things for which the Board can be criticized. Pure crapification, it seems to me.

One of my fave Board failures, as I’ve mentioned in prior NC comment sections, is the Board’s failure to enforce GAAP relative to SVB’s securities classifications. Another one of my fave examples for Board sub-par-edness, though perhaps lesser known then many other examples, is the Board’s (and other banking regulator’s) utter failure to move against predatory lending in the early 1990s.

I am also concerned that the Board’s failure to control inflation creates space for people to argue that the early CV19-era spending programs were inflationary and that this country should therefore never again engage in such social spending. The CV19-era spending programs, perhaps the first wide-spread example of universal basic income in the US, did an enormous amount of good. It seems to me now, though, that progressive economists who care about poverty issues may have to engage in an exercise whereby they will allocate and attribute X percent of inflation to Board policy failures and Y percent of inflation to early CV19-era UBI/social spending. I don’t see that working out well.

Golf clap for the Board! Caveat: I’m not an economist, but am an interested and long-time observer.

And Z percent due to good old GREEDflation. Why is this so seldom included in the spreadsheets?

“We screw you because we can, and it’s actually a lot of fun!”

Check out the initial commentary for an insight – even a blind squirrel finds an acorn once in awhile…https://creditbubblebulletin.blogspot.com/2023/11/weekly-commentary-most-critical-stage.html

This may seem completely off-the-wall.. but Federal spending on Ukraine and other wars is off the charts and, like the weapons leaking out of Ukraine all over Europe.. could well be offsetting Fed tightening. It’s estimated that actual spending on war (as well as propaganda) is at least double the published numbers. I could be (probably am) wrong somewhere here, but it seems as if this source of liquidity is largely ignored in financial reporting.

And a dollar spent on a 155mm NATOUKRO artillery shell fired into the schools and markets and hospitals of Donetsk or Gaza has about zero multiplier effect on “the market” us mopes inhabit. But of course there will be “profit” from “rebuilding country 404, paid to the same people who hold all the Raytheon and LockheedMartin etc stock.

I wonder if the old-soft-shoe-side-step in this case is (at least partly) the CLO, collateralized loan obligation, comprised of senior loans, top of the capital stack, leveraged a further 10X. Makes a sort of synthetic bank which is not susceptible to a social media triggered run. They have been around for some years. They have some opacity, are poorly understood by those who play the ponies,

and are of growing interest to seniors with small portfolios chasing yield, such as myself.

Just my two cents.

Yves said:

Which of those forces are still operating?

– reduced labor force?

– supply disruptions?

– corporate price-rise opportunism?

– trade war with China or financial and military war with Russia?

– monetary value reduction via gargantuan increase in money supply?

The – by far – biggest elephant in the room is money supply expansion; it dwarfs the other factors, does it not?

Purchasing power of consumer dollar, last 100 years. St Louis Fed

And that’s been going on for decades. At some point, it’s going to show up as inflation, won’t it? Of course it will, and it has; it’s just a bit more blatant lately. The pace of inflation is quickening, and that’s all that’s different. The pace of inflation is quickening because the money supply expansion – all forms – is also quickening.

The supply shocks were mostly used as rubric to raise prices, and – thankfully – to raise wages some. That wage-rate spending blip won’t last long, because continued inflation will offset it. How many wage-rate leverage events do workers have at their disposal?

So now you’re the Fed. Your job is to contain inflation, but the only tool remaining to keep up the appearance of economic vitality is … to increase the money supply. But if you do that, you get more inflation – almost immediately. If you tap on the brakes (raise interest rates) the appearance of econ vitality takes a fast and obvious hit.

There aren’t any good moves left that don’t involve structural reform of the economy, and boy, that’s a risky move.

War isn’t working all that well. Former colonies are not cooperating as they once did. Investment and wealth creation is moving into regions the West doesn’t control very well.

What to do.

.

Wash your mouth out. Money supply has ABSOLUTELY NOTHING to do with inflation. They don’t correlate. That has been demonstrated repeatedly. Japan has had absolutely insane levels of money supply growth for two decades and could not get out of borderline deflation.

The chip shortages were starting to ease but we screwed that up with China sanctions: https://epsnews.com/2022/10/31/how-china-sanctions-will-further-disrupt-the-supply-chain/

Falling energy prices had lowered overall inflation rates but that is now reversing.

Greedflation is very much with us.

Labor markets are tight IMHO to those who can quitting (employment conditions poor, this is particularly true for doctors and nurses) and Long Covid sufferers working less or not at all. The US has seen a big increase in disability rates: https://www.americanprogress.org/article/the-recent-covid-fueled-rise-in-disability-calls-for-better-worker-protections/

If you want to blame a government action, it’s the big Federal deficit spending.

Two questions

If supply chain issues were the real culprit behind the inflation, why are prices not coming down now that those issues have been solved? Actually prices are on average 30 to 40% including real estate which seems to correlate with the increase in the money supply.

If money supply has absolutely nothing to do with inflation, why not have the Fed directly monetize all government debt and abolish taxation?

1. According to official statistics, inflation has come down. But as I indicated, many supply issues are NOT resolved, most of all labor, which is a much bigger component of costs economy-wide than any commodity, even oil. And greedflation has not gone away. Producers are increasing prices because they can, not due to cost pressures.

2. The Fed is not allowed to monetize even though it does briefly prior to Treasury issuance. In the US, deficits required to be are financed by bond issuance. It’s a holdover from the gold standard era.

I was also remiss in not pointing out that QE is not “money printing”. It is an asset swap.

I think we have to differentiate between asset price inflation and consumer price inflation as well. QE appears to have spurred huge stock and real estate price rises. The more recent CPI rises were caused by what Yves outlines. It seems clear that money supply increase = inflation is not valid.

Any good discussion should start by defining the meaning of the words and you are right, but what I mean by inflation is CPI + asset prices and I think it should be how inflation should be defined otherwise anything goes as can be seen with countless definitions that exist currently that are but a smokescreen to allow for stealth taxation of the workers.

“Wash your mouth out.”

:) That was great.

On to the points you made:

Japan is not a good contra-example. Japan is an export economy, and starting with Plaza Accord then Taiwan, Korea and then China their market share and margin on sales took an awful beating. The expansion of their money supply was intended as a _remedy_ to deflation – they _knew_ that expanding money supply would help offset the awful deflationary effects of reduction of export earnings on their economy.

In order to support your assertion that expanding money supply has nothing to do with the buying power of the incremental dollar, you’ll have to rescind the law of supply and demand. Name me any asset wherein you can expand its supply (a lot, and for a long time) and the incremental instance of that asset doesn’t also fall in price.

All the rest of the factors you named do indeed apply, but they are relatively minor effects. What (finally) unleashed the inflationary trend was that the dam broke.

The “dam” was a buildup of repressed price pressure (from monetary expansion, mouth not washed out yet) and the gradual lessening of the deflationary effect of cheap imports and low energy costs (still very low by historical stds, factoring in the declining purchasing power of the dollar).

Then Covid, which was cover for all manner of (heretofore repressed) price increases; Covid was the cover story for the dam breaking.

The supply disruptions are largely behind us; in fact they were a good bit made-up ( port clogging is a great example). Yes, labor costs did rise – it’s a brief interlude of labor prices making up a little lost ground. And yes, lots of corporate “greedflation” as you mention, and that’ll go on till the up-blip in household income subsides, and Wolf’s “drunken sailors” run of rum money.

At which point the money supply will again be increased substantially, and the current pretense of reducing the money supply via “tightening” will be (very skillfully, of course) … forgotten.

And as you point out, the Fed’s fiscal engine never got the memo about “restraint”. They’ve been expanding the money supply hand over fist. As you’ve pointed out to me many a time, the Feds spend money into existence.

Sorry but a ton of this is wrong. Japan did not take an awful beating after the Plaza Accords, although that myth is promulgated by the likes of Jeffrey Sachs. I was working with the top Japanese keiretsu and visited a ton of branches in Japan in 1987-1989 (corporate business was done out of branches). There was absolutely no sign of any problem. No bitching about poor growth or difficulty in making loans (as in loan demand).

Its exports as a % of GDP fell a bit in 1985, then returned to virtually the same level as before the Plaza Accords. Japan did lower interest rates to try to stimulate more domestic spending (and speed up the transition to a more consumption-led economy) but all that did was fuel financial speculation, when Japan already had scary big asset bubbles and very unsophisticated banks that went wild because the US forced deregulation to help US investment banks.

And in the post bubble era, the drag on growth was the zombified domestic economy. Exports continued to be strong, to the degree that some financial analysts thought Japan was overplaying how bad things supposedly were so that no one would bust their chops over their somewhat weak currency in the 1990s.

Japan ran absolutely off the charts massive monetary stimulus for over two decades and did not generate inflation. That alone proves money supply growth does not create inflation.

Yves: if there was no problem with exports, why the deflation? Why the sudden dependence upon expanding the consumer economy?

And if Korea, Taiwan, China were all producing the same tradable goods, and the cost structures of the competitors were lower than Japan’s, how could export revenue and profits not be affected?

Re: “proves money supply growth doesn’t affect inflation”.

The money supply increase wasn’t directed toward the consumer (as it finally was during the tail end of the Covid crisis); it was substantially directed into real estate, with the effect of increasing household costs, reducing disposable income, making a consumer-driven economy _less_ possible, making banks unstable, etc. as Michael Hudson has been telling us for years. ‘

Why wasn’t that huge money supply (and concomitant debt, all those new loans you mentioned) directed toward addn’l industrial plant?

Same reason it wasn’t done here in the U.S. – underlying cost structure out of whack, imports were cheaper (but not from Japan), additional investment was made in regions where underlying cost structures would actually yield profits (e.g. Mexico, Korea, China, etc.).

The U.S. didn’t get a big new flood of Japan-sourced manufactures during the time of deflation (and money supply increase), right?

I posit that if the money had indeed gone to the households, then inflation surely would have happened, just like it did here during the Covid event.

What I can’t quantify is the degree of Japan’s deflation, and then compare that to the inflationary effect of asset bubbles. That cross-effect may explain why there was “no apparent inflation”.

Maybe no CPI inflation, but surely asset inflation.

Here’s a related quote from the World Economic Forum:

….. and this one, too:

Stagnant wages suggest that Japan’s corporations either aren’t doing well, or they’re not sharing their profits with their workers.

The new loans were not directed towards industrial plant. They went into real estate, stock market speculation, overseas investments typically at bad prices, and to mid sized and small companies. Japan’s big international names behind them have many small and weak suppliers. Japan also had and still has fabulously inefficient retail. Many many little shops.

Thanks for that post, Yves. That helps me evolve my conception of the conditions under which the money supply can be expanded, and not have it result in inflation:

a. If the new money doesn’t get spent in the domestic economy (e.g. loans to other countries)

b. If the new money is used to create demand (e.g. real estate development) in an otherwise deflationary (demand destruction) environment (e.g. as a strategy to offset existing deflationary trends)

On the other hand, if the amount of money is sufficiently large, and is spent into an economy in near equilibrium (demand = supply), then you’re going to see inflation. If it’s spent into an economy that’s in supply deficit (demand > supply), then you’re going to see a lot more inflation.

And thanks for taking the time to explain all this to me, Yves. It must be frustrating, but keep in mind that we _are_ listening, and we _ do_ appreciate you.

What drives inflation is war time spending funded using debt and the economic conflict which results from that spending.

I will second Yves in all this, I’m an economist who specialized in Japan after working in a Japanese bank at the peak of the bubble … in Eurodollar syndicate loans to Latin America, that is. I was on sabbatical (a Japan Foundation grant) living in Tokyo for a year at the peak and initial downturn of the bubble in 1991-92. And so on.

Manufacturing economy? export-driven? Look at the numbers. They are a service economy – their late 1980s boom was driven by construction, not international trade. Again, I saw that first-hand, and not just in the data. Plus at the time I read 2 different Japanese business newspapers each day, and met with businessmen in a wide array of industries, and attended Japanese academic conferences in a couple different fields, and co-taught a course (in Japanese) at a leading law school.

Back to Wolf Richter, who cried wolf too many times for my taste, I stopped reading him 10+ years ago…short-term US macroeconomic performance is driven by construction/real estate and automotive, those are the volatile components of GDP. So interest rates, not liquidity.

In closing, kudos again to Yves, who is also right that we don’t have data for a lot of things that matter. Large parts of the financial system operate in unregulated or lightly regulated areas. Without regulation, there’s no reporting requirement. And as we saw with credit default swaps in 2008, even industry players have no way to know what’s really going on. Again, I saw that first-hand. One of my last projects before heading off to grad school in 1980 was to call around to Citi and Chase and BOA and First Chicago and the other big players in the eurodollar market and swap information on credit limits to Brazil (I worked at the long-defunct Bank of Tokyo, then the leading Asian player in many global markets). What I found was that everyone was at their ceiling, from direct lending to forex exposure to letters of credit to domestic operations (Bank of Tokyo ran a branch banking operation in Brazil, a legacy of largescale migration in the early 1900s of Japanese farmers recruited to open up new land). No one knew – not us, not Morgan, not the IMF, and certainly not Brazil, though within 6 months new credit dried up as more and more banks maxed out their exposure limits and others saw what I found. By then though it was too late, for the Bank of Tokyo (which was idiosyncratic in its reliance on international business, and was dissolved into merger) and for Brazil.

Mike: Thanks for that detailed reply.

This chart shows Japan’s exports as pct of gdp period 1970- 2020. Note what happens to exports @ 1985 (plaza accord). Took Japan almost 20 years to repair the damage to export earnings.

Japan did indeed stimulate other aspects of their economy, resulting in the bubbles you mentioned (same as U.S. did, btw, and with the same sort of results): Japan’s wage growth stagnant for decades (OECD chart in link).

While you may say “Japan is a service economy now”, you’d say the same about the U.S. How’s that working out for us? And why did we emphasize “service”? Because our export markets dried up, for the same reasons that Japan’s did. Competition.

And note that Japan’s moving their economy back into export-driven mfg’g after their experiment with service-driven economy. Refer again to the export as pct gdp chart above for verification.

You mentioned that you had tangential or direct involvement in Japan’s banks making loans into the developing world. Why, why would they do that if their export markets were healthy and growing? They’d invest in additional mfg’g capacity at home.

For those readers that would like a first-hand account of the impact the Plaza accords and Asian competition for markets had on Japan’s industrial investment decisions, see this article from Nippon.com that details the story of Japan’s once-dominant position in semiconductor manufacturing.

The question remains: why the deflation? I say “because wages stagnated, and they stagnated primarily because their biggest income source (mfg’g) faltered for decades”.

And where was all the new money that was created applied? Apparently it was used to fund construction and create a bubble, the destruction of which destroyed a lot of that money (does that sound familiar?).

And some was used to make loans in other countries … since it wasn’t deemed profitable to make those loans in Japan.

Money is not an asset. You can’t eat money, you can’t build a shelter with it, you can’t “consume” it. Money is a placeholder for assets. It is a reductionist fallacy to treat it as if there were literally a “supply” or “demand” for it, because 1) there is literally an infinite supply (because it’s made up), and 2) said ‘demand’ is ALWAYS artificial (because the government demands it for taxation). While it might be useful to see it that way in the paradigm of the closed-loop financial system, that reasoning breaks down when you try to relate it to the wider economy, actual goods/services and peoples’ behavior.

Anon:

There are a lot of accountants that will differ with you. Cash (money) is always classified as an asset on any entity’s balance sheet.

Money is (almost) always exchangeable for tangible assets, like food and energy. Unless the money you have is not currently exchangeable for other assets, it’s an asset.

“Exchangeable for” is not the same as “being”… a philosophical difference perhaps, but interestingly: it is because we forget money is an abstraction of value (and not value itself), which enables all manner of transmutation (and redistribution) of real value, so prodigiously documented here on NC. Not to mention crypto.

The money supply is both an asset and a liability. How can this be?

Because of double entry accounting with assets=liabilities + equity. The creation of money is sometimes called expanding the central banks balance sheet, because when assets are increased on the left side of the equation, liabilities have to increase on the right side to keep the equation balance. Likewise, the destruction of money causes the contraction of the central bank’s balance sheet.

The case of japan is indeed curious, and seems to be an outlier as in all other cases where money supply was increased, Milton Friedman has, I think convincingly showed that the outcome was corresponding inflation (provided the velocity of money – a very hard variable to calculate – remains more or less constant).

I think the jury is out on Japan, maybe Friedman will be proven right in the end, the issue being that in a globally integrated complex economy (and their proximity to China which I think was the major cause of low global inflation for the last 30 years) the lags between monetary policies could be indeed very long.

However, the supply chain issue does not seem to explain why prices haven’t come down by now.

Also dismissing the money supply argument seems specious as it gives the impression of no limits to how much money can be injected in an economy, so if $8 trillion in the Fed’s balance sheet don’t matter why not $80 trillion then?

Greedflation might be a valid argument but it does not explain why people got greedy all of the sudden in 2020 and not during the periods of low inflation we had before imho.

Curious indeed. I think Richard Koo has professed that Corporate Japan needed to pay down its massive debts and they may still be at it. Also the Japanese are savers. The carry trade? How much of that $$ was lent to speculators who we know never take losses and always need more $$.

Whatever the causes, and there are many imo, The financial wizards never sleep and are always up to no good.

>>>Greedflation might be a valid argument but it does not explain why people got greedy all of the sudden in 2020 and not during the periods of low inflation we had before imho.

There is the increasing monopolization of most of the American economy by the corporations, which means that there are not enough competitors to go to and even if there is someone, they likely have greedflation as well. Then add the mania for always having increasing profits and since the real economy is still a wasteland despite the small increase in manufacturing because of the forty years of hollowing the economy, insanely raising prices is the easiest and often the only way to get that extra profit.

in an anti competitive environment such as the one we live in once prices are raised there’s no reason to lower them

https://www.investopedia.com/terms/s/sticky-down.asp

FTL…

Sticky-down prices may be due to imperfect information, market distortions, or decisions to maximize profit in the short term.

…and the long term

No. Friedman was wrong.

Milton Friedman proved nothing. His monetarist theories have been decisively debunked, and monetarist experiments, as I pointed out, all failed too. There are a lot of appealing stories in economics that do not pan out in practice. We have a long discussion in ECONNED, how the most paradigmatic relationship in all economics, the upward sloping supply line intersecting with the downward sloping demand curve, does not hold in a tremendous cases. Even the slope of the lines often does not hold locally.

Let’s not forget U.S. economic sanctions (Russia, Iran, Venezuela et. al.) as a government action aggravating inflation.

Ugh. Will this vulgar Monetarism zombie NEVER die? Central banks stopped trying to control the money supply 30 years ago because commercial bank loans create deposits — period.

Our company got $1.2million in PPP money which was forgiven and deposited in the bank.

How does this fit in your description of money creation through loans.

All that liquidity has juiced up the markets and portfolios leading into 2024. The eventual crash will be harsher as more bad events play out around the globe.

Thanks, Joe, and all the rest. :/

Fed is still doing QE via BTFP , buying impaired bonds at face value, it will be interesting to know the size of their purchases since SVB debacle, that will give an idea of the size of new QE done to date this year.

https://www.federalreserve.gov/financial-stability/bank-term-funding-program.htm

part of the problem is that the NFCI is constructed to use a lot of spreads. ( eg, headline mortage rates v 3 mo t bills, corporate spreads, and CDS).

the current macro US problem isn’t spreads; the too-big-too-fail banks are in fine shape. so are large companies.

The problem is the effects of nominal interest rates and personal consumption, see >10% used car loans.

we are see high interest rates finally affect the proverbial minnows… see .used car sales slowdown.

won’t be long until the great minnow die-off hits the whales

Or could it be that the US government threw a whole bunch of extra government spending into the mix in Q3/Q4 last year, just as the US stock market looked increasingly vulnerable and kept the pump priming going ever since? All that “Ukraine” spending tends to end up back in the pockets of defence contractors in the US, so every dollar helps the economy. Nothing like a 5% GDP plus level of government deficit spending to offset the higher interest rates and QT.

Without any further increase in the US government deficit we should see some real impacts coming shortly, as long as Powell doesn’t lose his nerve. Actual real interest rates for a while would do the trick.

This seems right to me — it’s awfully hard for the US economy to tip into recession while the US Federal government is running record “peacetime” (LOL — Ukraine + Gaza, but hey, no Congressional declaration of war, amirite?) deficits.

Rock and a hard place? If consumers are 80% of the economy, the Fed has to keep them financed. Is it a big ponzi driven by financial profits or can consumerism level off in a perpetual balance between Fed infusions, rising inflation and higher interest rates, and higher wages? Otherwise it will crash, right? I haven’t seen any comment on how overvalued the dollar has become and how far it has to fall to become competitive. There is clearly a goal in all of this. The Fed knows better than Congress what it will take to prevent 1929. And the push to rev up the MIC is blatantly obvious, from selling off our old stock to Ukraine, to BS about running out of ammo, to better fighter jets, to the Pentagon officially making statements to gin up space aliens, etc. We just fall back on old familiar patterns. It would be nice if the engine of the economy, world-wide, could transition into sustainability and environmental protection and repair. Which transition could entail giving the US Military a new mandate. We’ve already got a zillion bases and outposts which could be coordinated on a local level for every conceivable environmental project. So my only question at this point is how do we switch from an environmental-destruction-profit-engine to an environmental-protection-profit-engine? And let the money flow like water. Clean water.

Yes. My eyes tend to glaze over with the various terms and explanations with QE and related issues. However, I think that the people running the economy do not understand that the hollow economy of today is not the robust economy of their childhood, military Keynesianism is about the worst kind of stimulus long term, and the money needed to build factories, plus the medium and small businesses, and to keep that 80% of the economy going is not coming through. I keep reading about all the money floating around, but I am not seeing it in regular people. If it is coming through, it is being eaten by the increasing cost of housing, food, medical, and education.

We can hate and rightly blame the Fed for much of this mess, but really, it requires Congress to have a long term industrial policy that is very well funded with additional funding for the state and municipal governments to do what they see is needed locally. Reversing the cuts in the child tax credit, SNAP, and Medicare again would also be a serious help for that 80%.

But Congress has gutted its structure for effective legislation and the increasing dysfunction and centralization of power into a handful of leaders means that it is becoming harder to actually create and fund that industrial policy.

I also have to add that all these bubbles seem to a complete waste of money as they create nothing at all useful except long term risk for catastrophe.

I wonder what sort of legislation it would take to require an industrial policy plan and update every 5 years that accounted for the assets and benefits accomplished by said plan instead of accounting for the tokens used as the means, medium of exchange, like a catalyst, to create the real assets and benefits. The way we account now is by making the catalyst the end goal and treating the benefit as just another “expense.” Effectively hoarding the catalyst. It’s almost moronic because we automatically devalue money by spending it when it should be accounted for in just the opposite direction. That’s why it is so important, for example, to prevent crypto from ever being allowed to be an official sovereign-backed currency. Crypto is a private asset, as it is designed. Counterfeit notwithstanding. Nobody sees the contradiction because it is so ingrained in our perception of money that money as an asset. Money is only as valuable as what it is able to accomplish. Bottom line, money is cooperation.

How to stop liquidity when deficit is 7% of gdp? That pushes about 140b/month into the economy, though a little leaks into Ukraine. The treasury giveth, the fed Taketh away thru high rates.

Granted treasury mostly gives to the wealthy bond holders and mic etc, not the struggling underclass (formerly middle), who can’t buy/sell homes while the wealthy can pay cash. According to plan.

I’ve watched reverse repurchase for a while.

Thursday the overnight sale of bills to banks broke below a trillion first time since the fed started tightening.

Before the great printing of green backs in 2020 and 2021 rev repo was very small. It hit over $2.2 trillion in summer 2022. Every time reverse repo goes down either the fed lets increased liquidity or bank reserves declined.

Recently the rev repo discount bills at 5.3%.

There remain about a trillion or so bank reserve with no place but to be lent overnight to the NY Fed.

Lots of liquidity!

So much for monetary policy … I thought the consolidation of u.s. commerce and industry also had something to do with inflation and the way wages have trouble keeping up. Between the structure of u.s. commerce and industry and the capture of government and regulatory bodies — it is getting harder and harder to blame capitalism for the manifold boils festering and consuming the economy and body politic.

WOW this topic always brings out the money cranks and via it the ideology behind it that has no retrospect to history and accounting – nada historically. People with out any education or relevant life experience in the guts of it opining from painted corners of some philosophical room. Then on top of it all make out like its the wellspring of all human woe and if we all just ascribed to some wobbly notion of money we would all be saved … rim shot …

Bill Mitchell has a good article up on his blog talking about Japan’s current approach and how it is diametrically opposed to the western approach.

https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=61341

Highly worthwhile to read; thx for the link, Jonhoops.

And btw, it bolsters my points made above re: Japan’s deflationary experience, so I like it even more. :)