By Casper Worm Hansen, Professor of Economics University Of Copenhagen, and Asger Wingender, Associate Professor of Economics University Of Copenhagen. Originally published at VoxEU.

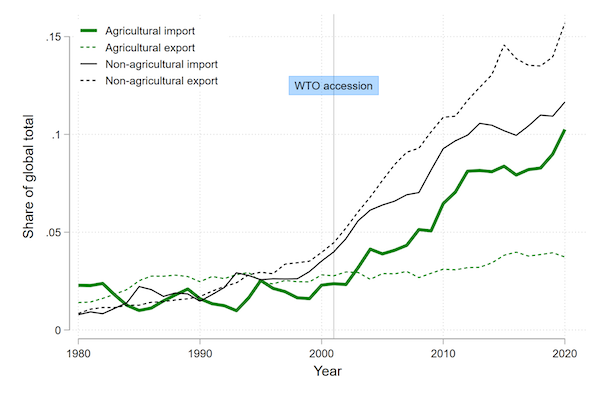

China’s emergence as the world’s leading manufacturer has created headlines for decades. Scores of research papers, policy papers, and newspapers have documented what shiploads of cheap Chinese goods meant for manufacturers, workers, and consumers elsewhere (see Assche and Ma 2011, Acemoglu et al. 2014, Hombert and Matray 2015, Marin 2017, Feenstra et al. 2018, and Rodríguez-Clare et al. 2022). To feed its manufacturing industry, and economic development more broadly, China became the world’s largest importer of fossil fuels and minerals. The black curves in Figure 1 clearly illustrates the relentless rise of Chinese manufacturing in terms of both exports of final goods and imports of inputs. Also visible in the figure is another, less publicised shock to the global economy: after joining the WTO in 2001, China quickly went from being a net exporter of agricultural products to being the world’s largest importer. China currently imports more than 10% of all internationally traded agricultural goods, and more than 5% of global agricultural production.

Figure 1 China’s trade in agricultural and non-agricultural goods

Note: Agricultural import is the dollar value of Chinese imports of agricultural goods relative to the total value of internationally traded agricultural good (green curve). The other variables are similarly defined. The vertical line indicates China’s accession to the WTO in 2001.

That China as a consumer of agricultural products has drawn far less attention than China as a manufacturer would strike an observer from the 1990s as odd. With its large population and its increasing taste for meat, it was a legitimate concern whether global agriculture could satisfy increasing Chinese demand. “Who will feed China?”, asked Lester Brown in an influential article of the same title (Brown 1994). In the article, later expanded into a bestselling book with the subtitle “Wake-up Call for a Small Planet”, he predicted that with just 0.08 acres of grain land per capita, and little room for further expansion, China would soon have to import large quantities of food (Brown 1995). Farmers around the world would struggle to expand supply to meet Chinese demand, Brown warned, and the resulting steep increase in global food prices would be disastrous for the world’s poor.

With the benefit of 30 years of hindsight, we revisit Brown’s question in a recent paper (Hansen and Wingender 2023a). How did the world manage to supply China without apparent disastrous consequences for the world’s poor? And what about the broader question of how global agriculture adjusts to large demand shocks? The empirical literature contains few answers, which may seem surprising until one realises how hard it is to disentangle cause and effect. Trends in global demand are usually gradual and intertwined with demography, technical change, and other factors simultaneously affecting supply, not to mention that supply growth by itself may lead to higher demand. But in this particular case, quirks of Chinese trade policies allow us to discern the causal effects of a large demand shock to global agriculture.

Self-Sufficiency and Surging Imports

China started to ease restrictions on imports of soybeans and a few other crops in 1995. Although a more substantial liberalisation of agricultural imports followed China’s accession to the WTO in 2001, China still kept a policy of self-sufficiency in important food crops, notably maize, rice, and wheat. The policy was introduced in the 1960s shortly after the famine caused by the Great Leap Forward, when food security became a pillar of legitimacy for the Communist Party (Zhan 2022). The Party reconfirmed the policy in response to the publication of Brown’s book to assure global leaders that China could indeed feed itself. To this day, China imports almost nothing of the crops covered by the self-sufficiency policy, but large quantities of other agricultural products. Countries and regions specialised in the crops covered by the policy were consequently far less exposed to rising Chinese demand than other places. We use this variation in exposure to Chinese demand to trace its effects from the global level to the country level and down to the local level in Brazil and the US, China’s biggest agricultural suppliers.

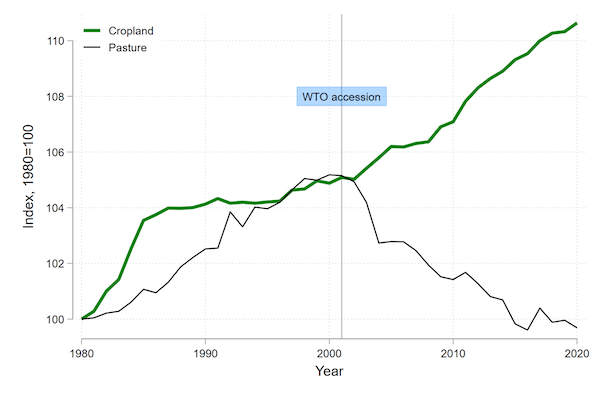

Chinese Demand and Global Land Use

Across all levels of aggregation, we find that farmers met Chinese demand by expanding cropland rather than by increasing yields. The response was so large that it is visible with the naked eye in global data. The green curve in Figure 2 shows that the extent of global cropland, which had been stagnating for a decade, began to increase after China liberalised imports of certain crops in 1995. The pace increased after China joined the WTO in 2001, leaving the extent of global cropland 7% larger in 2020 than in 1995. Our statistical analysis indicates that Chinese demand caused this entire increase.

Figure 2 Global land use

Notes: The green curve is global cropland. The black curve is global pastureland. We index both variables to 1980=100. The vertical line indicates China’s accession to the WTO in 2001. China began liberalising import of soybeans and few other crops already in 1995.

That farmers expanded crop cultivation to meet Chinese demand benefited consumers, who did not experience soaring food prices, as Lester Brown predicted they would. Farmers benefitted, too, at least in the US, where detailed agricultural census data allow us to show that profit margins rose in areas exposed to Chinese demand.

The low food prices and the high profits came at an environmental cost. Much of the expansion of cropland came from cultivating land formerly used as pasture, as also suggested by the black curve in Figure 2. While conversion of pasture did result in a loss of biodiversity, an even greater loss of biodiversity came from expanding production into areas previously untouched by agriculture. We find that Chinese demand for agricultural products was the likely cause for between one third and two thirds of global deforestation since 1995.

Lessons and Perspectives

As its population declines and economy slows, China’s demand for agricultural products will grow at slower pace in the future, but global demand will keep rising fast thanks to other big countries in Asia and Africa (Fukase and Martin 2016, 2020). Will the world be able to feed these countries, too? Our results suggest that it might. Pasture still constitutes more than half of global agricultural land, so further conversion of pasture into cropland could meet much of the shortfall. Such intensification reduces biodiversity, however, and our results suggest that global forests will continue to be under pressure as well.

The trade-off between food security and environmental degradation in a world with a rising demand for calories and animal protein can only be eased by increasing crop yields. High-yielding crop varieties associated with the Green Revolution and genetically modified crops have, for instance, substantially increased agricultural production without any expansion of cropland, on balance leading to better outcomes for both the environment and the poor (Gollin et al. 2021, Hansen and Wingender 2023b). Further investments in such innovations should have a high priority for both humanitarians and environmentalists.

Nice graphs. Not mentioned is the gigantic waste of food whereby nearly half the calories produced are thrown in the garbage.

https://www.cbc.ca/news/science/food-waste-un-reportx-1.5936245

900 million tons of food in the garbage

Then we get to the ridiculous amounts of fake food of which I include poisons such as Pepsi and Coke. Trucks guzzling diesel to deliver that diabetes inducing crap is insanity. Yeah, Captain Greed, WB makes billions poisoning the population, and is revered for it so it must be all good.

And why do we waste so much food? Supermarkets and restaurants.

Thank you! This needs saying every time someone mentions food waste.

The food waste narrative otherwise becomes like recycling or carbon footprint, a personal responsibility.

All of these are artifacts of capitalist complexity and concentration, converting ecological devastation into money profits, systemic problems that can only be effectively addressed at the systemic level.

The biggest irony comes when media writes about people helping themselves to thrown out prepacked salads etc, and in response the supermarkets putting locks on their dumpsters rather than work out some system of donation.

And don’t forget the most insidious and most inescapable poison of all, High Fructose Corn Syrup (“HFCS”), which is in almost every food in the U.S., even baked beans!

HFCS is addictive and rewires the brain to make you crave more sweets. The “bad” (i.e., “thrifty”) buggies in gut your gut biome LOVE HFCS, and the rise in obesity in America tracks the rise of consumption of HFCS fairly closely.

It’s worth emphasising that a huge proportion of these imports are not feeding Chinese people. They are feeding Chinese pigs. The Chinese taste for pork – which is intimately tied to notions of wealth and progress – (like the French ‘chicken in a pot on a Sunday’) – is doing enormous environmental damage, as much as the American taste for oversized trucks. Current Chinese government policy is to persuade people to eat more chicken than pork due to the birds more efficient use of feed.

At some stage we will have to face the reality that while we may be able to feed the planet in the future, we can’t if meat consumption continues to rise. Probably one of the biggest climate changes ‘fixes’ possible would be viable synthetic meats if they could be produced sustainably.

Likewise, a great deal of Spanish grain imports are for pig & chicken feed. Spain, I believe, was the greatest beneficiary from the grain deal.

Yep, seen a fair bit about that in Norway as well. Talking about how the feed for cattle etc is grown in cleared out parts of the Amazon and like.

While i was growing up the feed was mostly hay, many a summer spent packing it away for winter while the sheep was off grazing in the hillsides.

May be I am old fashioned, but I find the idea of artificial meat bizarre. If you want to replace a hamburger with a legume-based protein rich product, you can eat falafels — I spend a year in Germany where Syrian and Kurds (my particular neighborhood) made excellent pita sandwiches, I did not see anything as good in USA, in particular their combination of falafels and salad vegetables.

But there is still a ton of options to have healthy tasty meals with less meat or no meat. Do we need science to reproduce tasteless hamburgers?

Meat is perhaps the original conspicuous consumption.

Korea has an excellent system for helping support its desire for pork and reducing total food waste. Food waste is meticulously segregated from trash, even in multi-high rise apartment complexes in Seoul. It all goes to pig feed. That doesn’t solve the factory farm waste output from pork production, which at the scale we’re discussing becomes a significant problem regardless of meat type.

Maybe they should look into going thunderdome, and run their energy grid on pig manure?

Everyone awhere, WH Group acquired Smithfield in 2013. Environmental restrictions in the US are less strict than restrictions in China…

Another change from 1994 was the emergence of Russia as the world’s largest grain exporter in 2020. In the ‘90s Russia’s ag sector was “reformed” & Russia imported half its food. Post 2014 investments brought the Russian ag sector back from the dead, and having become a huge grain exporter, they’re now exporting chicken, pork, & beef.

China has just done a $25b food deal with Russia.

The Chinese government does not want world domination, but it does want all Chinese to live like Americans. That would mean that all Americans would have to live like the Chinese.

https://www.statista.com/chart/24350/total-annual-household-waste-produced-in-selected-countries/

It seems the Chinese are already there, when it comes to food.

Does that mean that we all “meet in the middle” and all live like Chinamericanese?

To tie in with recent news articles, Iowa is a huge pork producer as well as corn for animal feed. Hence President Xi’s connections there.

Did not know about the switch to chicken. The problem there is that chicken is a poor replacement in many favorite foods, especially dishes that use ground pork. Eat more three cup chicken, drunken chicken, three pepper chicken, chicken broth, etc. Silkies are considered higher end food, so that’s not a problem.

This is a poorly concocted, self-contradicting attempt to shift the blame and to provide a thin veil of justification for the hand-wringing we see in the West as the Global South develops. The author closes with a hint at the appropriate solution, but fails to mention that the solution already exists.

Let’s break it down.

The above quote is preceded by the following:

So which is it? Did Chinese demand that caused the increase in cropland? Or did the farmers, by expanding cropland rather than increasing yields?

And here:

The above is followed by this non sequitur:

Here again, the author blames increased Chinese demand for causing a loss in biodiversity, when it is already plainly stated that the choice to expand cropland was “made by farmers”.

“Made by farmers” is an obfuscation. These “farmers” are primarily gigantic land-holding monopolies and agri-tech monopolies managed by banks and investment firms looking to maximise profits and rents.

And here the hand-wringing about Global South development:

On the other hand, the final paragraph starts finally in the right direction but misses the mark:

This is correct. However:

This final concluding statement omits the fact that we already have environmentally friendly agricultural methods to meet the current and projected demands by increasing yield and without expanding cropland. However, these methods are far less profitable than the currently-used destructive practices. Instead, the author prefers to continue and increase investment in the very same process that has caused the devastation he appears to be concerned about.

The expansion of cropland to meet rising demands for food is caused by the capitalist/imperialist organization of production. This is a conclusion such economists as this author train their whole careers to skirt around. Their job is to carefully and meticulously place curtains around the elephant in the room.

This article did a poor job of explaining, but the Chinese eating more protein (as in higher up the food chain) has had a significant environmental impact. Investment guru Jim Rogers said IIRC in the early 1990s that China meeting the official target of one more egg per person per week would require a massive expansion of global grain supplies. I don’t recall the exact # but it was something like 40%.

Thanks for your reply. It’s undeniable that Chinese eating more protein increased demand for grain supplies.

As I mentioned, the agricultural practices to satisfy all this demand by increasing yield without expanding cropland already exist. No new technologies are required. What prevents them from being adopted (and indeed, tends to force them out of existence by the process of monopolization) is that they are significantly less profitable production methods.

On the other hand, the solution proposed by the authors is to invest in innovation. What does this mean? The lion’s share of such investments is taken up by the very same monopolies that ensure the destructive practices stay in place. These investments are directed to further increasing profitability, and perhaps a little bit of green-washing on the side so that they look like they are solving problems. More kicking the can down the road.

My conclusion is that if we really want to solve this problem – and we do need to solve it – we need to dismantle this system of production and replace it with a new one.

So it doesn’t matter that the article did a poor job of explaining the link between protein and grain. Overall it really looks like plain obfuscation. At best, it is ignorance of the topic, in which case they shouldn’t be writing about it.

As “profit” doesn’t just seem to be the priority, this evidence demonstrates it actually is, I see no reason to expect any changes as long as there is no accounting for damages.

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/pesticides-are-killing-the-worlds-soils/ and https://www.wsj.com/us-news/cancer-risk-pesticide-california-farmworkers-864174b2

Couldn’t agree more.

The existing food, energy and housing infrastructure is way beyond its sell-by date. We’re just struggling with the inertia of change resistance, not technology development.

But we won’t dismantle anything until we build viable alternatives, and that means a lot more people need to get involved in new product development and implementation … like all those labor-saving and local ag production methods ISL alludes to below.

The change is not going to come from the top; oligarchical, profit-driven (.vs. values-driven) operations will not do the changing for us.

If your core values include a viable biosphere, it might be time to look for or build some alternative products.

People are doing exactly that, as you’re reading this. It’s not that big a leap anymore.

Unforeseen developments in global grain trade include the unexpected recovery of Russian wheat production and exports from net importer to worlds leading wheat exporter, India’s rise and fall as wheat exporter, and Brazil’s safrina corn or 2nd crop increasing supply. Degradation of production lands remains problematic as do animal protein diets, animal “flu” of any kind, and of course the politics of food. Supply chains seem vulnerable, weather and climate uncertain, and genome of grains set for exploitation.

**High-yielding crop varieties associated with the Green Revolution and genetically modified crops have, for instance, substantially increased agricultural production without any expansion of cropland, on balance leading to better outcomes for both the environment and the poor (Gollin et al. 2021, Hansen and Wingender 2023b). Further investments in such innovations should have a high priority for both humanitarians and environmentalists.**

Or, we could have less humans instead of “genetically modifying” the ones we have by spraying chemicals all over the entire world and driving to extinction the species that depend on the habitat. But, I’m guessing the article was written by “orthodox” economists, which, consider the source:

https://theintercept.com/2023/10/29/william-nordhaus-climate-economics/

I had seen somewhere a list that China was dominating and growing rapidly in agricultural production of a wide range of categories – having trouble finding, but China is 33% of tomato production.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_tomato_production

and something like 87% of the global spinach production.

There are lots of videos like this:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y5ESBDJ1UqE

on China’s high-tech investment in high-value, intensive agricultural production (leveraging access to high-tech, low-cost manufacturing), IMO indicates the global agricultural industry will evolve along similar trends as with Chinese manufactured products. Focusing on Pig feed is missing the forest for the trees.

** Note, I have a microfarm where we produce all our veggie needs and give away to neighbors (S. California) from ~650 sq feet. We use many time, labor-saving, and efficiency-improving products from China, which are way way cheaper in China (or if ordered in bulk directly allowing for long lead times) than from US Ag suppliers.

Side note: Our food waste virtually all goes to our chickens.

Nice work, ISL; we’re following parallel paths.

I expect China to become a world leader in local-loop production methods, which enable the waste re-use, soil-building (nutrient cycling), distributed, low-density greenhouse and high-tunnel based food production .. especially where the soil and climate don’t support conventional (outdoors, year-round) production. The energy for these systems can readily be supplied by wind and solar renewables.

China might be wondering if it’s still a good idea to empty the countryside, concentrate workers in cities, and then import a lot of food to feed them. Might be better to move the work to the countryside, and do more distributed mfg’g. Like mfg’r all those labor-saving and environmental control tools (easy to mfg’r) in regional or even local facilities near where the people used to live, and might yet return to.

It’s also possible to manufacture high-thermal-efficiency building materials on a distributed basis, often using indigenous materials. Buildings fritter away about the same amount of energy as our current internal combustion engines do here in the U.S.

It’s not like we can’t do this; the technology and materials are already more than sufficiently developed and available.

This is why China has become such a big problem with unregulated / illegal overfishing worldwide.