Yves here. Once in a while, there is some good news on the environmental front. I wonder if the same trend toward lower city speed is operative in Europe, or if they were already pretty tame due to greater bike prevalence and perhaps also winding streets.

I also find it funny that the story is mainly about Seattle but the photo is obviously of New York City.

By Sarah Wesseler, a writer and editor with more than a decade of experience covering climate change and the built environment. Originally published at Yale Climate Connection

(Image credit: Anubhav Saxena on Unsplash)

Since 2015, Seattle has lowered speed limits across much of its road network, setting residential streets at 20 miles per hour and most larger urban corridors at 25 miles per hour. After these changes took effect, studies showed that car crashes fell by approximately 20%, while the crashes that did occur resulted in significantly fewer injuries.

Cities across the U.S. are following Seattle’s lead, with speed limits dropping from Denver and Minneapolis to Washington, D.C., and Hoboken. Although these changes are motivated by the need to reduce deaths and injuries from car crashes, there’s a growing recognition that they also benefit the climate.

“Safety and environmental goals go together. They’re inevitably interlinked,” said Venu Nemani, the chief safety officer of the Seattle Department of Transportation.

High Speed Limits Are a Barrier to Climate-Friendly Transportation

Transportation is the largest source of emissions in the United States, and passenger vehicles are the leading offenders within the sector. Electric vehicles can help reduce these emissions, but they’re not a silver bullet — many experts agree that meeting climate targets will also require car use to fall. As a result, it’s vital for governments to help people meet their needs by walking, cycling, and taking public transportation (which often requires traveling on foot to a transit stop).

But achieving this will require making streets safer for people moving around on foot or by bike, as concerns over road safety are a common barrier to walking and cycling. Unfortunately, these concerns are justified. According to the World Health Organization, more than 1 million people die on roads every year around the world. More than half of all deaths and injuries from crashes involve vulnerable groups such as pedestrians, cyclists, and motorcyclists.

In the United States, pedestrian and cyclist fatalities have risen in recent years against the backdrop of a wider road system failure that kills tens of thousands of people annually.

“We have a traffic death crisis in the U.S.,” said Alex Engel, senior manager of communications at the National Association of City Transportation Officials. “Traffic deaths are unbelievably high, especially compared to our peers. They’re getting worse, for a variety of different reasons.”

Vehicle speed plays a major role in these incidents, with faster motion leading to more and deadlier crashes. Higher speeds are especially dangerous for people outside cars. According to the AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety, a pedestrian struck by a vehicle traveling at 23 miles per hour faces a 10% risk of death. At 46 miles per hour, this rises to 90%.

A Global Push for Safer Streets

The movement to lower speed limits in U.S. cities represents a much-needed break with the past, Engel said.

“The way we’ve set speed limits in the U.S. for decades has been really quite outdated, and it was based around essentially pseudoscience,” he said.

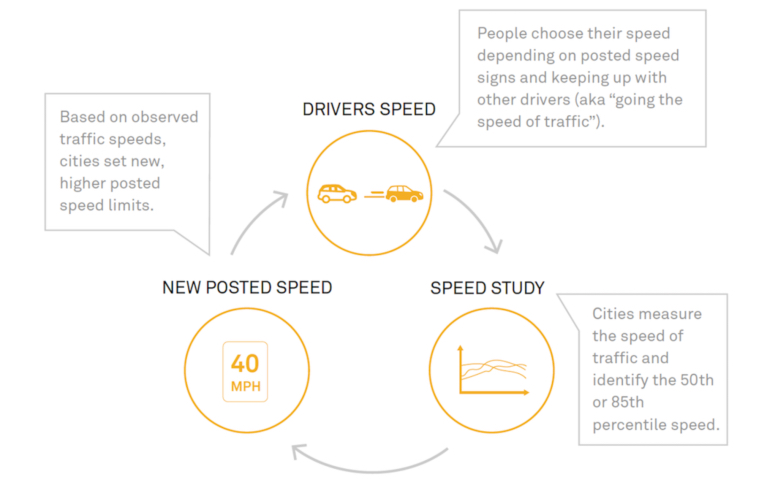

The traditional method essentially allows drivers themselves to determine speed limits. In this model — still used in much of the country — transportation officials measure the speed at which all cars on a particular road are moving during a given period with no traffic congestion, then determine the speed above which the fastest 15% of this group are traveling. This number (rounded) then becomes the new speed limit for the road. However, since some drivers travel above the posted limit, this approach causes speed limits to rise over time.

Efforts to move beyond this approach have been inspired by international precedents. Vision Zero, a strategy first adopted by Sweden’s parliament in 1997, has been particularly influential. Whereas traditional approaches to road safety emphasize individuals’ responsibility to prevent crashes, Vision Zero focuses on creating a system in which human error — which is impossible to completely eliminate — is less likely to cause serious harm. Some of the measures used to achieve this include reducing speed limits, redesigning streets (by adding roundabouts, for example), and mapping crashes to enable stronger interventions in hot spots.

Another force shaping the global debate over traffic speeds is 20’s Plenty for Us, a volunteer-driven organization based in the United Kingdom. The group was founded in 2007 by Rod King, an avid cyclist who experienced the benefits of 20-mile-per-hour speed limits while visiting the bike-friendly city of Hilden, Germany. Variations of the campaign’s name have been adopted as a slogan by transportation agencies and advocates, with “20 is plenty” appearing everywhere from buses in Washington, D.C. to yard signs in Salt Lake City.

Policymakers across Europe and the U.S. have been receptive to Vision Zero and 20’s Plenty ideas. According to King, in the United Kingdom, 28 million people — nearly 42% of the total population — now live in a 20-mile-per-hour community. London has lowered its speed limits, as have Brussels, Paris, and other European capitals. At the national level, Spain and Wales have set default limits of 30 kilometers per hour (around 19 miles per hour) and 20 miles per hour, respectively, on many roads.

Designing a Safe Transportation System

Wen Hu, a senior research transportation engineer at the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, has examined the effects of lower speed limits in Seattle and Boston. She said that these and similar studies from other countries have largely confirmed that lowering speed limits brings real benefits. “Basically, all this research tells the same story: Reducing speed limits can reduce speeding and reduce crash severity.”

Drawing on studies from Hu and others, “City Limits,” a 2020 report published by the National Association of City Transportation Officials, concluded that the relatively simple act of changing speed limit signs can lead to a significant return on investment for municipalities. “A growing body of evidence in places like Seattle, Boston, and Toronto shows that drivers respond to posted speed limits even without any enforcement efforts,” the authors wrote.

But lower speed limits alone can’t completely eliminate crashes, of course. Hu cautioned that while speed limit reductions are effective, they need to be combined with other safety-focused interventions. “It’s not as simple as you just reduce speed limits and that solves the problem,” she said.

The intervention most familiar to many Americans — police enforcement — is far less than ideal, according to “City Limits.” The report’s authors write that police disproportionately stop people of color when enforcing traffic laws and that police-led speed limit enforcement can have damaging unintended consequences in communities of color.

Instead, the report says, the most effective way to slow traffic on streets where speeding is common is to change the physical design and operation of the street itself; for example, by adding speed humps and reducing the length of green lights at stop signals. Speed cameras can also help.

Seattle Redesigns Its Streets to Protect Cyclists and Pedestrians

In recent years, Seattle has successfully redesigned a number of streets to slow traffic, said Clara Cantor, a community organizer with urban advocacy group Seattle Neighborhood Greenways. However, some streets still encourage speeding, and a high percentage of the city’s 28 average annual traffic deaths occur on these corridors.

“There’s still some streets in Seattle that are really designed like highways and feel like you should be driving on it like a highway. And that’s where we’re seeing most of the major crashes where people are dying,” she said.

And though lower speed limits alone aren’t enough to prevent all deaths or change every driver’s behavior overnight, they play a crucial role in “the long game,” as Cantor put it. “Now, when SDOT (the Seattle Department of Transportation) is going in on every single one of those streets, any little tiny project that they’re doing, they’re designing for a lower speed limit than they would have been otherwise. And so over time that’s made a really big impact on a lot of streets.”

Seattle Neighborhood Greenways is still pushing the city to do more to protect cyclists, pedestrians, and transit riders, but Cantor said that even for cynical transportation activists, the department of transportation’s progress since adopting Vision Zero is impressive. The experience of biking around the city “is completely, completely transformed from how it was in 2016,” she said. “It’s way, way, way, way, way better and feels safer.” The public transportation system has also become more robust, she noted, and pedestrian access has improved.

These changes have made it easier for people in Seattle to get around without cars. “Over the last decade, our population grew by about 20%, and during the same time our traffic volumes pretty much stayed the same on our [street] network, and our transit user ridership has grown by about 30%,” said Venu Nemani. “We are basically providing more and more options every day for people of the city of Seattle to make their trips by using non-auto modes.”

According to Rod King of 20’s Plenty for Us, setting the stage for wide-ranging changes like these is a common benefit of 20-mile-per-hour speed limits. This makes speed limit reductions a critical first step for cities wanting to improve road safety and reduce emissions.

“The speed of vehicles affects your [road] crossings. It affects what you have to do to protect cyclists. It affects what you have to do to protect other motorists,” King said. “So get the speed down — get the kinetic energy in a road network down — and you will find you have more options.”

” taking public transportation (which often requires traveling on foot to a transit stop)” <– It is heart warming to read unexpected discoveries made by intrepid reporters. In this case, the report possibly went as far as taking a few public transit trips herself. But indeed, it is not THAT obvious, in my town many buses have bicycle racks in front is so you can get to a bus stop and from bus stop on bicycle. Add foldable electric scooter, accommodations for wheelchairs…

We’ve had 3 infections & PASC, since 3/20 & I’ve never been as upright about SARS-CoV2 damage as about our sneeringly brainwashed MASKLESS mouth-breather neighbors on e-scooters, unicycles & 80lb unlit delivery e-bikes cutting in and out of speciously obliviousness coots like us, on sticks, walkers or in chairs (vindictively ignoring lights, traffic, strings of babies, sirens & locals staggering like Redd Foxx on ether, kvetching into iPhone 15s @ 98dB. E micro-mobility COULD make a HUGE difference in a city, NOT run by dead-eyed kleptocracts, FOR sneering multinational oilgarchy (who’d murdered 1.8M sero-naive Chinese, to SHORT successful AGW mitigating equities).

“After these changes took effect, studies showed that car crashes fell by approximately 20%…”

More importantly, I bet police revenue from automated roadside speed camera systems increased by an order of magnitude.

Vision Zero emphasizes redesigning the streets in conjunction with reducing speed limits. That includes curb extensions, protected bike lanes, speed bumps, raised pedestrian crossings, protected intersections, etc.

Jersey City managed to get to zero traffic fatalities in 2022.

And to answer Yves question, European countries have actively change their regulations to move car centered development into more pedestrian and bike friendly cities. Not Just Bikes has a 22-minute video essay of how Oslo made a major change of direction in 2015. Norway is an outlier in EU in terms of auto ownership, so they had to deal with decades of policy.

There are a number of quick and easy ‘wins’ in transport planning – lowering speed limits is one that should be mind-blowingly obvious but is rarely implemented for ‘reasons’ (i.e. motorists vote). The irony is that lower speed limits frequently speed up speed to destination – slower steady traffic is less likely to knot up. Anyone who has travelled around Japan will note the very different environment very slow traffic speeds create, even in otherwise congested areas.

It has to be said that the US and Canada are major outliers in transportation planning – almost everywhere, from Europe to Asia to Latin America, its recognized that reducing emissions and increasing safety is more than just a matter of providing buses and bike lanes. There is simply no good reason for allowing 2 tons of steel to be moved around urban areas at more than 20mph. Sometimes this is done implicitly by road design (this is the norm in much of Europe), the use of enforcement should be a fall back, not the sole method.

Of course the big question is why any car is allowed to be sold that can break the speed limit. The technology to put speed limiters on cars has been around for decades, but mysteriously has never been mandated for vehicles. As we face a proliferation of non-car/truck EVs this will become ever more important.

I have a car that I drive only once or twice a week. I walk from my home in the suburbs two miles to the MBTA station, I try to do most of my shopping and errands on foot either during my commute or consolidated in trips.

I’m bringing this up because I’ve noticed how cyclists have completely dominated discussions about changing road behaviors at the expense of pedestrians. Notice how cyclists and bikes are put first in both the article and Seattle’s policies. Whenever the topic of road safety comes up, the conversation is completely dominated by cyclists, with very little attention paid to pedestrians. And at least in my experience, cyclists tend to be younger, wealthier, and better educated than pedestrians. This has resulted in roads that have added bike lines while decreasing visibility at crosswalks; increased signage, but less predicable behavior from drivers, cyclists, and pedestrians.

Does King care about pedestrian safety? I’m assuming yes, but when quoted in the article, he only said that we need to protect cyclists. If we want to improve road safety for everyone, we need to treat all groups separately and implement policies that they will actually follow. And this means not conflating cyclists and pedestrians; they are different groups with different needs, concerns, and road usages, which need to be reflected in debates and government policies.

Here, dozens of HEAVY, clunky poorly maintained e-bikes are made available, at the top of a twisting 70′ 12% drop into a VERY verdant, shady park crowded with boomer yuppies, e-bike food deliveries infants & kids exiting a playground, pushed by coughing au-pair or sneezing parents on iPhones & dog-walkers. Kinda like a Woody Allen remake of The Road Warrior?

It’s been a while, but I don’t recall Hoboken or DC drivers to be even slightly concerned with the speed limits in force at the time.

Some of us are so old we can remember when Nixon declared a 55 mph limit on all interstates. This may have gotten him impeached /s

https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/nixon-signs-national-speed-limit-into-law

And just the other day LA Times on cyclists being “doored.”

https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2023-12-19/what-is-dooring-the-bicyclist-collision-that-killed-a-hollywood-producer

The truth is that cyclists and pedestrians are going to need a much bigger lobby if they expect to change the current dominance of the real estate and highway lobby. Only separated bike lanes are truly safe and those can threaten walkers if reasonable bike behavior not enforced.

Which comes to the other problem which is lack of enforcement. The reason those 55 mph limits were dropped was that hardly anybody respected them without highway patrol nearby.

Comparing cities in the US and in Europe is ludicrous to say the least. And then the focus is on the few cities on the coasts lol. Good stuff. Here in Houston… oh by the way, environmentally speaking my gas mileage is better on the city roads…

As someone who lives in Seattle – the lowering of speed limits is virtue signalling to the nth degree.

No one follows the speed limits here. There are no traffic cops to enforce the speed limits or any other driving rules due to the police staffing crisis that followed the whole “defund the police” movement”. Multiple police left due to that misguided policy and a bunch more left due to the vaccination mandate in 2021. They have not returned and the staffing levels of the police in this city are less cops per capita than the city had in 1995 when the population was 200,000 less people.

The city can redesign streets all they want, however the city won’t acknowledge that most of their pedestrian fatalities are people who are mentally ill, drugged up on something, or just out of it who wander across the street in traffic without any regard for themselves or what’s around them and keep telling themselves that it’s the evil car drivers who are the problem. The city refuses to acknowledge reality and the root cause of the problem in multiple areas.

I’ll just say that as a lifelong cyclist I strongly disagree with the attitude that bikes are legal vehicles and therefore must assert their rights by sharing the streets with cars in places where that is quite dangerous. It simply doesn’t work and kills a lot of cyclists.

Neighborhoods, sidewalks (legal or not), special trails are the place for bikes.

Or, alternately, everybody or most people ride bikes like used to be true in Europe.

Hey, Brian, it’s Slim here in Tucson! And permit me to offer a big, hearty amen to everything you just said.

Here in Tucson, our pedestrian fatalities are way up there, and, just like Seattle, the same causes lead here. Lotta broken people wandering out into traffic, with predictable results.

Our police numbers are down considerably, and for the same reasons as Seattle. It’s sort of like stupid on steroids.

As for redesigning streets, there was a big intersection painting party about a mile and a half away from the Arizona Slim Ranch. The project includes plastic bollards, and wonder of wonders, they haven’t been knocked down yet.

Stated reason for all of this redesigning was to slow the traffic, but I’m not convinced that it’s actually happening. If anything, I’m even more cautious while I’m bicycling through this intersection.