By Lambert Strether of Corrente.

In a recent — and very stimulating — discussion between Michael Hudson and Steve Keen, a question arose: When was the term “capitalism,” er, coined? This intrigued me, and being a glutton for punishment, I thought I’d look into “capital,” and “capitalist” as well.

I should caveat right away that, as far as possible, I’m looking at the emergence of the words in context (source, nation, date) with meanings as understood in normal commercial life. The post is in no sense systematic, it’s totally not an intellectual history, and it’s Anglo-Centric, since English is the language I speak, and English tools are the tools I have. The post only covers what Bourdieu would call economic capital (and not social or symbolic capital, even if understanding those two forms of capital has great potential for understanding why capitalism is so anti-fragile).

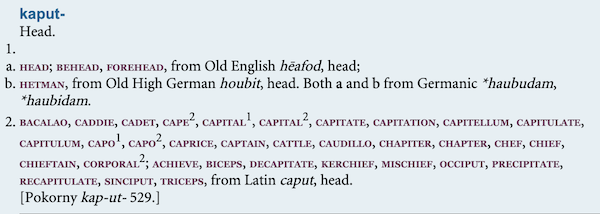

Here is the Indo-European root of “capital”, kaput (!):

(I love this stuff. From the root, branching out: “capital”, “caprice,” “cattle,” “caudillo,” “chef”….) Historically, “capital” comes first, followed by “capitalist,” and lastly by “capitalism,” and I will take the terms up in that order. First, a perspective that applies to all three from Stephen Stoll, “The History of ‘Capital’“:

So complete has capital become throughout the social order that it appears to have emerged from the natural order, and the behavior it instills seems to many people to be an expression of universal human motives and aspirations. As three historians observe, “One of the distinguishing features of a free-enterprise economy is that its coercion is veiled … Far from being natural, the cues for market participation are given through complicated social codes [social capital, symbolic capital]. Indeed, the illusion that compliance in the dominant economic system is voluntary is itself an amazing cultural artifact.” It might be true that the gentry did the same thing in 1650 that they did in 1250. They extracted value from people and environments. But they did it differently than anyone had before, through a discipline imposed by rents and wages, through social codes and cues that appeared to be independent of people. They aren’t. Perhaps the most radical idea we can have about capital, the single most subversive thing we can think about it, is that it begins as nothing more than a relationship between people. Like the meanings of words, relationships change.

Of all the insights of the people who coined “capitalism,” I think that is the most important, if not exactly mainstream.

Capital

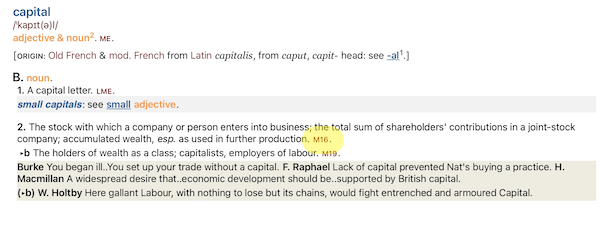

My Oxford English Dictionary (OED), dates “capital” to M16, that is to the middle of the 16th Century CE:

Frederic Pryor, in Capitalism Reassessed, “Appendix 2-1: Etymology Of ‘Capitalism’” gives the word’s history after the Indo-Europeans but before the English glommed onto it, as we do (which is why English is such a wonderful language and there are so many volumes to the OED[1]):

[The word “capital”] comes from the Latin words capitalis, capitale, which in Western Europe in the Middle Ages designated, among other things, “property” and “wealth.” (Berger, 1986: pp. 17-18). In classical Latin, however, “property” was designated by a different word, namely caput. The Thesaurus Linguae Latinae (1906-12, vol. 3: 43-34) provides examples of this usage: for instance, around 30 B.C., Horace employed it to indicate “property” in his Satire 1 (Book 2, line 14). Several decades after Horace, Livy also employed the word with roughly the same meaning. A common derivation linking “capital” to “head of cattle” (hence wealth) appears to be incorrect.

(On “cattle,” the American Heritage Dictionary would appear to disagree. “Infinite are the arguments of mages” applies to a lot of the derivations here presented, and, I think, to etymology in general.) Franz Rainer, in “Word formation and word history: The case of CAPITALIST and CAPITALISM” adds a twist:

[B]y the time that the first derivative, capitalist, appeared, capital generally referred to the property, not necessarily only money, that a rich person owned. In double-entry bookkeeping, the term referred to the net worth owned by the merchant after taking away the liabilities from the assets.

(Rainer’s scholarship is a real pleasure to read, and if you have the time to sit with it, I recommend you make a cup of coffee and do so.) Sadly, Rainer doesn’t footnote when and where the double-entry bookkeeping usage appeared, but it would be pleasing if it were Italy, where double-entry bookkeeping (at least for the West) first propagated, and even more pleasing if it were one of the Italian city-states where, at least according to Giovanni Arrighi (The Long Twentieth Century) capitalism originated. Rank speculation! We turn now to a later addition to our stock of words, “capitalist.”

Capitalist

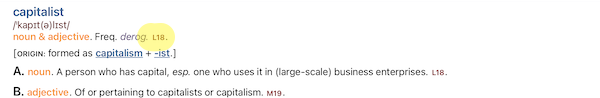

My OED dates “capitalist” to the late 18th Century:

It’s interesting that we have a word for the thing relation, “Capital,” and had to wait two centuries to have a word for the owner of the thing relation.

Here we turn again to Rainer, “Word Formation,” whose research is exhaustive and properly sourced:

[T]he noun Capitalist was indeed coined in the Netherlands (then: “United Provinces”) back in 1621 by tax authorities in order to designate a wealthy citizen who possessed 2,000 guilders or more… [For the] Dutch Capitalist was a complex concept, designating at the same time a wealthy person, mostly engaged in money-lending or investment activities, as well as a category of the tax authorities.

And:

The 17th century is called the “Golden Age” in Dutch historiography, because the United Provinces at that time were at the forefront of trade, military, science and art. This background, especially their eminent position in international finance, explains how a Dutch neologism could spread abroad and start an astounding international career. Already by the end of the 17th century, we find loan translations in German and French. German Capitalist (today written Kapitalist) appears as early as 1671 in a document on the financial system of the United Provinces, where, due to its novelty, it is glossed as ‘money-lender’ The German word, as far as I can see, had no influence on French.

“Capitalist” now hops to France, rather like a virus on an airplane, still in Rainer’s telling:

The few examples that we find in French until the middle of the 18th century…. refer to that same Dutch reality. In the second half of the 18th century, however, the noun capitaliste firmly established itself in French with a reference independent from the Dutch context. Here is a quote from the Dictionnaire domestique portatif (Paris: Vincent 1765), vol. 3, p. 505: “RENTIERS; ce terme est synonyme à capitaliste, c’est-à-dire, à celui qui fait valoir son argent, en le disposant suivant le cours de la place, & qui vit de ses rentes.”The diffusion of the term among a wider public was furthered by its adoption by the Physiocrats [Turgort, 1788], an economic school that began holding much sway at that time, in France and abroad.

(Sadly, “rentiers” is out of scope for this post.) Finally, “Capitalist” now crosses both the Atlantic and the Channel to the English-speaking peoples[2]:

Nowadays we strongly associate capitalism with the Anglo-Saxon world, but the truth is that Great Britain and the United States were the last among the big, developed nations to take up the word capitalist. In English, capitalist does not make its appearance before 1787, when the following example is attested in Madison’s [(!!!!)] writings… “In other Countries this dependence results in some from the relations between Landlords and Tenants in others both from that source and from the relations between wealthy capitalists and indigent labourers.” Four years later, the word is used in England by Edmund Burke…. There can be no doubt that French was the donor language for the English calque.

(A “calque” is “a word or phrase borrowed from another language by literal word-for-word or root-for-root translation” (English “hamburger” to French “hambourgeois”). And so to the final addition to our word hoard, “capitalism.”

Capitalism

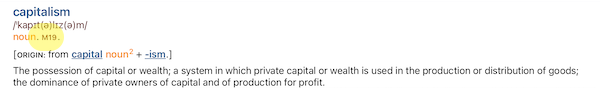

My OED dates “capitalism” to the middle of the 19th Century:

So, from move from the relation, “capital,” to the person playing one of the roles in that relation, “capitalist,” and then to the system in which those players play those roles, “capitalism,” takes about three hundred years.

Here we have two different narratives that, so far as I can tell, do not intersect. First, Rainer:

[C]apitalist acquired the sense ‘entrepreneur’ after having crossed the Channel (and the Atlantic), a sense that migrated back to France from the 1830s onwards, where it has cohabitated with the original sense ever since. Capitaliste, in that way, became the antonym of ouvrier, travailleur (both ‘worker’) and prolétaire ‘proletarian’, just like capital ‘capital’ had become the antonym of travail ‘work’. This lexical opposition simply reflected an extra-linguistic phenomenon, namely the well-known social divide created by the Industrial Revolution. In the 1840s, French capitalisme was also attracted by this lexical field and thereby was converted into the standard designation of the new economic system characterized by the exploitation of workers in factories owned and often run by a small group of capitalists/entrepreneurs. Here are some of the first examples of this new sense, which are probably attributable to Louis Blanc: “Une lutte récemment engagée entre Lamartine et L. Blanc a donné naissance à un nouveau mot ; le capitalism. Ce n’est pas au capital, s’écrie ce dernier, que nous avons déclaré la guerre, mais au capitalisme ; c’est-à-dire, sans doute, aux capitalistes“

(Louis Blanc was a French utopian socialist.) Importantly, from its formation, “capitalism” was always explicitly oppositional both in nature and in conception:

[T]he new lexical opposition [of capitalism] with socialisme and communisme could be viewed either as a consequence of this conceptual change, or as its trigger. In fact, the relevant meaning of these two terms, namely an ‘economic system where the means of production pertains to the workers or to society as a whole’, called for a designation for the opposite concept of an economic system where the means of production was concentrated in the hands of a small group of wealthy individuals. Since this means of production was referred to technically as capital and the entrepreneurs had come to be called capitalistes, capitalisme was a natural choice. This reconstruction of the word’s origin also neatly explains why the word was used with negative connotations right from the beginning: it was launched by the opponents of capitalism, while capitalists themselves and circles close to them used to call the then prevailing economic system libéralisme (économie de marché ‘market economy’ is of much more recent vintage).

The second narrative comes from Michael Sonenscher, “Capitalism: The word and the thing.” Here again “capitalism” is oppositional, although framed by post-1789 French reactionaries, rather than utopian socialists:

[A] number of royalist publications that began to circulate before and after the French Revolution of July 1830 [used the word, inspired by a Royalist named Bonard]. Here, capitalism became a shorthand for a fusion of two related problems. Behind the political question of the type of constitution suitable for the new regime, there was also, they argued, a social question, which asked whether any or all of the constitutional arrangements established by the July Monarchy were compatible with the combination of the division of labour, public debt, and inequality that, they claimed, were the hallmarks of capitalisme. No simple constitutional adjustment, they argued, could erase the legacy of the French Revolution. Real closure would have to come from erasing the French Revolution itself.

Capitalism, in this setting, began as a French royalist and legitimist concept that was designed to expose the limitations and fragility of the Restoration settlement and July Monarchy. It also, more importantly, began as a real political problem since the original concept of capitalism was a palimpsest of many of the most morally and socially explosive issues to have arisen over the course of the eighteenth century and the French Revolution: from war and debt to constitutional crisis and social dissolution. Positioning the concept of capitalism in a context that, right from the start, was significantly more apocalyptic than that of an industrial revolution or an economic category helps to explain the urgency and intensity of efforts made to understand the nature of the thing itself.

Whether from the right or from the left, “capitalism” propagated rapidly until “legitimized” in Germany in 1902. Rainer once more:

A more interesting conceptual change occurred at the beginning of the 20th century. At that time, academic circles began using the term not only to refer to the contemporary economic system, what we now call industrial capitalism, but also to economic systems of past times that, in their opinion, presented sufficient similarities with the contemporary system to be called capitalism. Proto-capitalism was located in the Renaissance, in the Middle Ages, or even in Antiquity. This conceptual change, which was the result of conscious conceptual manipulation for scientific purposes, resulted in a more abstract concept of capitalism, freed from some of the more contingent aspects of 19th century industrial capitalism, as well as its negative overtones…. [T]he international success of this scientific sense was certainly due to the publication, of Werner Sombart’s monumental Der modern Kapitalismus [in 1902].

After 1902, of course, came 1917[3], after which “capitalism,” still oppositionally charged, exploded into the American media environment of that time. From Steven G. Marks, “The Word ‘Capitalism’: The Soviet Union’s Gift to America“:

As the press conveyed the earth-shattering events occurring in Russia they adopted the word “capitalism” en route. Nearly every New York Times article that mentioned it in the 1920s had to do with the Soviet Union and its rulers Lenin, Trotsky, and Stalin. Simple reporting on the USSR required adoption of the term, and editorializing necessitated defining it. The definitions varied according to the political orientation of the writers and publications. By 1919, the first Red Scare was in full fury, and conservatives in the US were denouncing Bolshevism as a ‘menace to Americanism.’

Fast forward to the present day:

[M]y purpose has been to call into question what we really know about capitalism by showing that at nearly every moment since the word came into use it was defined by way of comparison with the dreaded Soviet Frankenstein economy. As a result, American conceptions of capitalism have been, and still are, imbued with what Samuelson once called the economic ‘science fiction of the right as well as of the left and center.

Let me close by quoting Christine Lagarde, “Economic Inclusion and Financial Integrity—an Address to the Conference on Inclusive Capitalism,” in a speech before the International Monetary Fund:

Capitalism originates from the Latin “caput”, cattle heads, and refers to possessions. Capital is used in the 12th century and designates the use of funds. The term “capitalism” is only used for the first time in 1854 by an Englishman, the novelist William Thackeray—and he simply meant private ownership of money.

Holy moley. But I don’t have time to put on yellow waders. Perhaps, armed with this post, readers can pick apart LaGarde’s words….

Conclusion

I should really have a terrific peroration here, but since the goal of the post was purely to explain, perhaps not. Once again, the moral:

So, from move from the relation, “capital,” to the person playing one of the roles in that relation, “capitalist,” and then to the system in which those players play those roles, “capitalism,” takes about three hundred years.

That’s a long time to rectify the names. Are we doing any better today?

NOTES

[1] Sadly, my printed Shorter OED, the one with the magnifying glass, which I got as a signing bonus from the Book of the Month Club, is gone where the woodbine twineth. All I have now is an app!

[2] I am guessing many usage examples could be gleaned from the “Positive Good” theorists in what would become the Confederate States. From George Fitzhugh, Cannibals All, 1857:

The capitalists, in free society, live in ten times the luxury and show that Southern masters do, because the slaves to capital work harder and cost less, than negro slaves.

[3] Here is an interesting discussion on the issue of whether The Bearded One used the word “capitalism.” From his letters, yes he did.

>>>The capitalists, in free society, live in ten times the luxury and show that Southern masters do, because the slaves to capital work harder and cost less, than negro slaves.

I think that capitalism’s greatest weapon is its ability to convince people who are essentially indentured servants at best that they too will have the ability to be as wealthy as the few successful robber barons are. Those barons then capture the extra wealth created by those hamsters in their wheels trying to become successful. Slaves in the Southern Slavocracy knew that they were slaves and therefore were not going to work any harder than they had to.

Then there is the corollary that if one has a chance to be successful, however unlikely it is, failure means a lack of will, virtue, intelligence, something in the failure’s self.

Also the slave owner has to provide for the slaves, the capitalist employer only have to pay the employees the agreed upon sum for the work done. If that is not enough to keep the employees alive, that is not the problem of the capitalist. At least until it starts to hurt his revenue.

> Also the slave owner has to provide for the slaves

That was in fact an argument of the “positive good” theorists (who weren’t stupid, and had a very interesting critique of “The North”‘s political economy). Of course, there’s the whipping part. And the slave block part.

Slavery could have been substantially improved by the slave states criminalizing the worst abuses of the slave owners.

I came across a meme online recently which said something along the lines of: “You are not capitalists. You are workers with Stockholm Syndrome”.

“capitalists themselves and circles close to them used to call the then prevailing economic system libéralisme”

This is the essence of “liberalism”. Capitalism itself. Bourgeois Ideology….

Wally Ballou interviews a paperclip magnate in Napoleon, Ohio, date hard to find.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QQna34cbPpg

Very pleased to see a fellow Bob and Ray enthusiast! Timeless values!

A quote from the Muslim theologian Al-Ash’ari (c. 874–936 CE):

A section of the people (i.e., the Zahirites and others) made capital out of their own ignorance; discussions and rational thinking about matters of faith became a heavy burden for them, and, therefore, they became inclined to blind faith and blind following…

The word “capital” in the above quote is a translation of the Arabic “ra’s mal”. The word “ra’s” means “head” and the word “mal” means “wealth, money, property, etc.”. So we have an example of the word “capital” as related to the word “head” from the 9th or 10th century, depending on when Al-Ash’ari wrote the above.

> The word “ra’s” means “head” and the word “mal” means “wealth, money, property, etc.”. So we have an example of the word “capital” as related to the word “head” from the 9th or 10th century, depending on when Al-Ash’ari wrote the above.

That is super-interesting. OTOH, capitalism seems not to have developed (metastasized?) in the Muslim world as it did in the West. I wonder why?

Rhetorical question?

The Quran supposedly hold a very negative view on usury, or lending at interest in general.

And isn’t that supposedly one of two things that the Dutch added to the Italian merchant formula? With the other being fractional reserve banking.

Christianity as well originally had a very negative view of usury.

Which is a major reason that Jews became bankers and merchants.

Great post. A question: If capital is a relation, then wouldn’t it be the person who owns/ relates to the thing. Rather than who owns the thing / relation? (Used italics because I couldn’t find the strike through)

There were machines before and after they were called capital. There were merchants with stock before and after it was called capital. There was land and coin hordes as well. Calling one of these things capital names the relation the person has to the thing, rather than the any quality of thing itself. (Those are trading tuna cans).

Not just the use of thing (for consumption or production) but perhaps the socially acceptable uses? A person who relates to a piece of land as his capital stock is licensed to use that land in particular ways. A farmer who owns land and sees it as his farm first will perhaps care for it differently than the farmers’ business school grad son who is also a farmer but sees the land first as capital in his business.

Similarly with money. It is possible to have a relationship with the money one has that contemplates its use in investment as just one of several options. Viewing it as capital limits what you might license yourself to do with it. (And is it self or society or both that are doing this licensing?)

So then a capitalist is one who (habitually, primarily, exclusively) views his relationship to his things as capital. And capitalism is what we call it when that view is widely prevalent in society.

The legitimization story is neat too. Look, we’re not weird for viewing everything as a thing to be used up for our private benefit. All these other people did too!

> the any quality of thing itself

I believe we are talking about the use value/exchange value distinction. In fact, the quality of the thing itself — the use value — is abstracted away; like the tuna can, all that matters is that it can be traded. Like human labor power (i.e., the power to imagine a different world, and invest energy in bringing it about (i.e., humans are things)).

Maybe not just use/tradr, but other values. A man might value land simply as a piece of his creator’s creation or for its use for the birds as habitat or a combination of things, one of which includes producing his livelihood. He might value a tool because it is well made and aesthetically pleasing. He might value his occupation because of his family history or just he value of a job well done. But if he values any of these things solely or primarily for its profit producing value (whether trade or use) then he has capital.

Calling something capital erases those values. If you have intellectual capital, it is to be used for profit (whether use or exchange). But if you have wisdom or knowledge you can use it for many other human purposes.

As you call more and more things capital, you see them more and more as tools for profit (domination/power you pick). And less and less are you able to see other values. Scrooge saw everything as capital (or only the capital value of anything). Until the ghosts removed the scales from his eyes and he saw other values and other purposes for the things in this world.

Or maybe I’m just a romantic

I think it’s useful to keep in mind how Marx thought of the relational aspect of capital. Although it certainly can be argued with, a virtue of the labor theory of value is that it highlights the fact that capital must be deployed to matter. As a thing it is nothing, a horde is just a pile of metal. When it is transformed into a means of production, it grounds a social relation. It becomes a way of producing use values to draw surplus value out of the laborer working with it, the surplus lying in the gap between the value the laborer produces and their wage. The capitalist might see his things as capital, but that would be because s/he has given over management of their wealth to others who handle the problem of realizing the relational potential of capital.

> capital must be deployed to matter. As a thing it is nothing, a horde is just a pile of metal

Ding ding ding ding. I think that is the most important unseen thing to see.

Also, “hoard”:

Fascinating, so thank you. But also, damn you for making me wonder about “rentier” now!

> damn you for making me wonder about “rentier” now!

Lots of Easter eggs in this post :-)

Related word Wealth. Different meanings but the one I am familiar with is that wealth is the product of labor….a man made thing … computer programs(recordings), music, houses, furniture, shoes, cultivated products, clothing and on – and that indeed wealth is most assuredly not money. So with a definition of Capital being either (Physical) the equipment, tools, building, labor and not money or Capital being money to exchange for physical capital or means of production– Physical capital represents wealth.

Money represents the value for exchange given to wealth.

I guess I am confusing myself – but trying to say that a definition of wealth and money are needed to define Capitalism. I prefer to distinguish between Finance and Industrial Capitalism and to further distinguish between the economic toll booths representing overhead and rentier actions and that of wealth creation – financial capitalism imposing a doubling of debt that always outpaces industrial wealth creation’s slower pace

I think you are on the right track. Toll booths are key and often overlooked. Here’s where I am:

Wealth:- Man-made goods, services and powers (being variously named ‘rights’, ‘privileges’, ‘property’, ‘patents’, etc.)

Bounty:- The gifts of nature. Under Capitalism bounty is often ‘privatised’ and counted as wealth.

Capital:- That subset of wealth which can be employed to produce more wealth. Usually one or more powers combined with none or more goods and/or services.

Money:- A measure of how much wealth one is owed or entitled to but is not currently in one’s possession.

Capitalist (Industrial):- One who employs capital, and if necessary labour, to produce more wealth.

Capitalist (Financial):- One who employs money, and if necessary labour, to gather more money.

Capitalism:- A system for producing wealth (for sale) in which the Capitalist has the unilateral power to allocate the proceeds, labour has to take what the Capitalist offers.

Socialism:- A system for producing wealth in which labour has the power to allocate the proceeds. The Capitalist, if there is one, has to take what labour offers.

Aaargh. Fungibility of language means nouns and verbs are interchangeable. Fungibility in finance means debits and credits are interchangeable. And when we get really confused everything is reduced to an adjective.

The best description, of the origin of the word capital, that I ever encountered was given by Frank A. Fetter in his seminal 1937 text “Capital, Interest, and Rent: Essays in the Theory of Distribution. Part 1, Essay 11. Reformulation of the Concepts of Capital and Income in Economics and Accounting”. This text was reprinted in Econlib. under the title “Accounting Review”.

Here follows a quote that summarizes Fetter’s thinking :

I added the ordered list to this quote as reference to what Fernand Braudel wrote about the epistemology of the word capital. In substance he confirmed Fetter’s 3rd phase when he wrote the following in “Civilization and Capitalism”, volume 1, The Structure of Everyday Life” (my translation from the French edition) :

This third phase must necessarily have taken place within the context of the Champagne fairs that were the beating heart of the emerging European space of commercial capitalism along the whole 12th century. See the excellent paper from Jeremy Edwards and Sheilagh Ogilvie titled What Lessons for Economic Development Can We Draw from the Champagne Fairs?. This is also the thesis that I defend in “Modernity 01”.

I knew the NC Commentariat would shake loose a subject matter expert! This is very useful because I don’t have Braudel to hand, and was unfamiliar with Fetter.

What I like about Rainer is that he is very, very close to primary sources. For all three phases, plausible though they are, I would like to see documents. (I also have the gut feeling that the intellectual history of the (three) term(s) is far more complex than high level analysis would indicate. And why not, if you think how capital dominates….

Nice work.

I think it would also be helpful to do a similar historical overview of the definitions/analysis of differing markets and how they were/are structured (say the historical transition from markets for output to the creation and development of factor markets (land, labor and capital) and their consequences.

Is there a process of sclerosis in market institutions (rise of financial markets)–where holders of economic .power consolidate their economic, political and legal dominance and then economic decline accelerates (Hudson and Keen seem, in part, to be raising/pushing this point).

Maybe there is a historical endogenous dynamic in markets themselves, which leads to stagnation and decline, as certain types of market elites become more powerful and coercive.

> Maybe there is a historical endogenous dynamic in markets themselves, which leads to stagnation and decline, as certain types of market elites become more powerful and coercive.

Interesting idea. I wonder what a good case study would be….