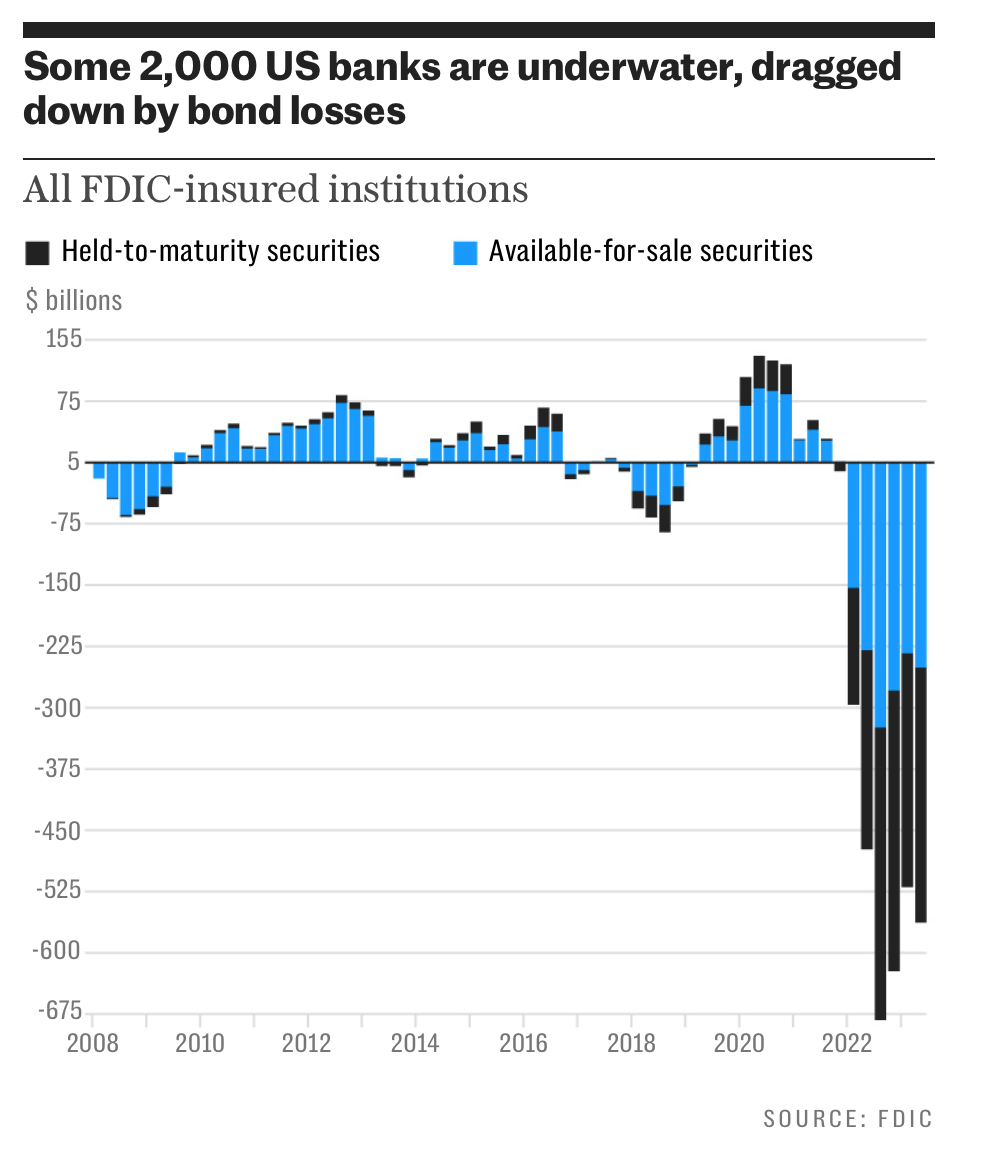

We pointed out last year during the Silicon Valley Bank and similarly-situated “too many supersized deposits” mini-panic that the bank tsuris was entirely the Fed’s creation. That bad spell of indigestion did not in and of itself point to a widespread crisis. The immediate cause (aside from inadequate supervision of deposit flight risk) was too many years of super low interest rates, which had lulled banks and investors into complacency about interest rates, followed by the worst possible action imaginable: a series of unprecedentedly fast increases in interest rates.

Despite these bad conditions, we didn’t think in and of themselves they were portents of more widespread bank industry distress. The Fed created yet another emergency liquidity scheme. But we mistakenly thought it would recognize the systemic risk of keeping rates high (by recent standards) for much longer and would back as quickly as possible out of its overly aggressive stance.1

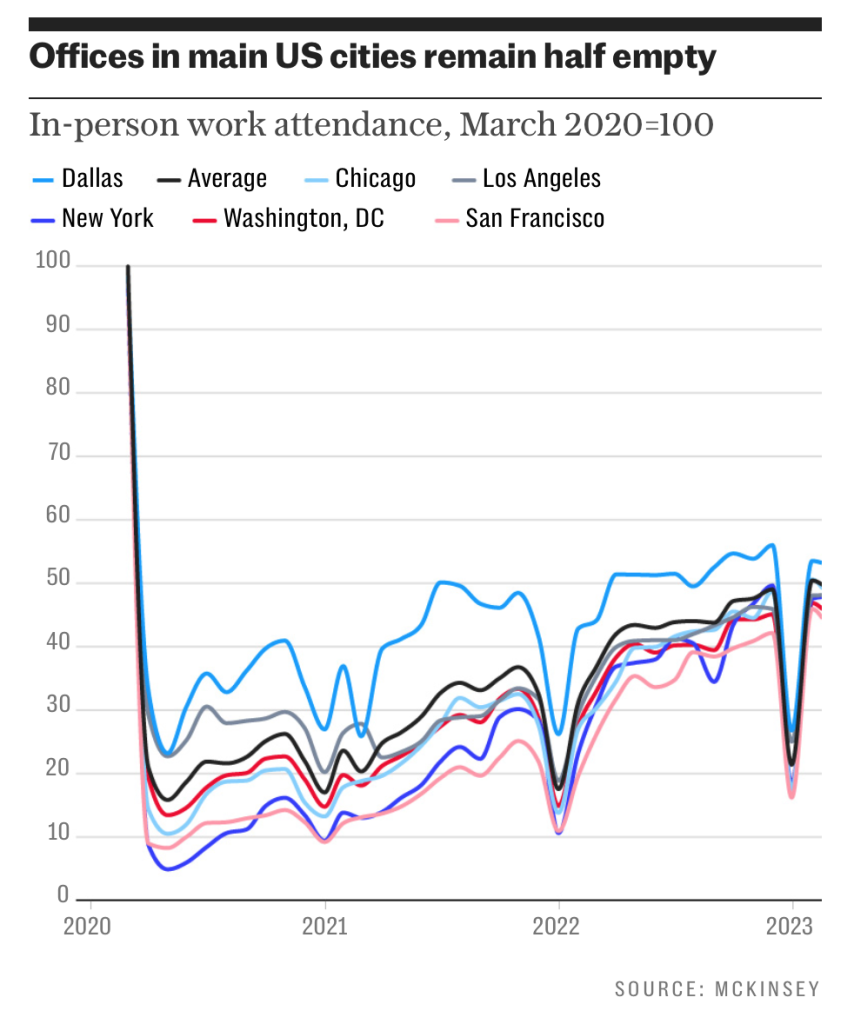

The fact that the Fed has been able to “emergency liquidity program” its way out of every major problem it created or at least could have prevented has made the Fed insensitive to the risk of blowing up banks. And so problems that could have been tamped down via corrective action a year ago are instead metastasizing. We’ll discuss two recent articles that provide supporting evidence, one a new piece at the Financial Times on expected losses at the biggest US banks, the second a much broader-scope look by Ambrose Evans-Pritchard, based on an NBER paper, on how continuing high interest rates plus too many cubicle denizens refusing to turn up at the shop every weekday is devastating the value of big city office space, particularly in less than prime buildings.

First to the Financial Times story, Largest US banks set to log sharp rise in bad loans:

Non-performing loans — debt tied to borrowers who have not made a payment in at least the past 90 days — are expected to have risen to a combined $24.4bn in the last three months of 2023 at the four largest US lenders — JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, Wells Fargo and Citigroup, according to a Bloomberg analysts’ consensus. That is up nearly $6bn since the end of 2022…

The current level of non-performing loans is still below the $30bn peak of the pandemic. The big banks have indicated they think the rise in unpaid debts could slow soon. A number of banks cut the amount of money they put away for future bad loans, so-called provisions, in the third quarter….

More recently though, delinquencies have been rising on consumer loans, particularly credit cards and car debt. That has made some analysts nervous, especially because what the banks are putting away for loan-loss reserves now is considerably smaller than what they set aside when bad loans were rising at the start of the pandemic.

Bank stock prices are rising, which for now offers considerable protection against a widespread crisis. When financial firms become distressed, their borrowing costs shoot up, which is an immediate problem since a lot of their funding is short-tern. So increase in borrowing costs can translate very quickly into losses and in a more dire scenario, an inability to secure debt funding in needed volumes. Lenders want the sick borrower to raise more equity so they have better protection against borrower losses. But when banks are having liquidity problems, their stock prices plummet, so that raising new equity becomes catastrophically costly (assuming it can be done at all…).

The very fact that big banks cheekily are not putting away as much as they have been to cover for possible loan losses can be viewed as a sign of confidence. Lower loan loss reserves also boost current profits.

But banks and investors are essentially betting on the Fed easing off on interest rates. That is not a given. December job growth was much better than forecast, but in and of itself, that sign of economic peppiness wasn’t enough to rouse interest rate worry-warts. However, the stock jockeys are arguably underestimating the odds of Red Sea shipping disruption blowback. From Business Insider (hat tip BC):

Inflation cooled rapidly across the world last year, but it might be a touch too early for a victory lap….

Shipping companies including MSC, Maersk, and Hapag-Lloyd, as well as oil-and-gas giants such as BP, have responded to the [Houthi] attacks by diverting their vessels away from the Suez Canal, the waterway that connects Asia with Europe and the US.

That means container ships are sailing around Africa’s Cape of Good Hope, making journey times about 40% longer, according to The New York Times….

The Houthis’ attacks are already driving up big shipping companies’ costs.

Drewry’s World Container Index, which tracks global container rates, jumped 61% over the first week of 2024, with the maritime research consultancy attributing the spike to the ongoing chaos in the Red Sea…

Journeys from Singapore to Rotterdam in the Netherlands were most likely to be affected by the disruption, with freight costs jumping 115% to as much as $3,600 per forty-foot box.

As well as causing significant delays, the threat posed by the Houthis has forced shipping companies to pay more for marine insurance – and they could respond by upping their prices in a bid to pass higher costs onto consumers.

The wild card is oil. Analysts so far have not expected Houthi action in the Red Sea to have more than a $3-$4 a barrel impact on oil prices. Experts think the Houthis would not threaten the Strait of Hormuz, which would presumably make Iran unhappy as well as seriously jack up oil prices. But what if the Houthis hit a tanker and make Middle East oil much pricier via both much higher insurance costs and shipper reluctance to transit while the area was too hot for their liking?

I remember all too well in January 2007 when the subprime crisis was supposedly over and parties that should have known better tried to catch that falling safe by buying subprime servicers.

Ambrose Evans-Pritchard is more dire, as in his wont, but he also provides much more substantial analysis than the pink paper did. His recent article, Fed rate cuts come too late to avert a fresh wave of US bank failures, relies heavily on a granular analysis published by the NBER, Monetary Tightening, Commercial Real Estate Distress, and US Bank Fragility. Its authors contend that (quelle suprise!) banks have been understating the severity of their current and pretty likely losses on loans to office buildings. Lower interest rates will not bail them out of this distress by much, since it is driven by the lasting shift to work-at-home and the impossible economics of repurposing these assets. From their abstract:

We focus on commercial real estate (CRE) loans that account for about quarter of assets for an average bank and about $2.7 trillion of bank assets in the aggregate. Using loan-level data we find that after recent declines in property values following higher interest rates and adoption of hybrid working patterns about 14% of all loans and 44% of office loans appear to be in a “negative equity” where their current property values are less than the outstanding loan balances. Additionally, around one-third of all loans and the majority of office loans may encounter substantial cash flow problems and refinancing challenges. A 10% (20%) default rate on CRE loans – a range close to what one saw in the Great Recession on the lower end — would result in about $80 ($160) billion of additional bank losses. If CRE loan distress would manifest itself early in 2022 when interest rates were low, not a single bank would fail, even under our most pessimistic scenario. However, after more than $2 trillion decline in banks’ asset values following the monetary tightening of 2022, additional 231 (482) banks with aggregate assets of $1 trillion ($1.4 trillion) would have their marked to market value of assets below the face value of all their non-equity liabilities.

Ouch.

The authors depict this problem as savings & loan crisis level, not Great Financial Crisis level. However, what most choose to forget is the S&L crisis was expected to produce a much longer period of distress and slow growth than it actually did. The reason for less-than-expected damage was that Alan Greenspan succeeded in engineering a very steep yield curve, with the Fed dropping short-term rates dramatically while the yields on longer-term assets remained relatively high. That enabled the banks to earn much-higher-than-normal easy dumb profits by their classic strategy of borrowing short and lending long. They rebuilt their balances sheets comparatively quickly and were able to resume normal levels of lending.

Evens-Pritchard provides his usually fine, colorful exposition. From his account:

Emergency lending by the US federal authorities has bathed America’s struggling regional banks in short-term liquidity, disguising the slow-burn damage of the US commercial property slump…

“It’s not a liquidity problem; it’s a solvency problem,” said Professor Tomasz Piskorski, a banking specialist at Columbia University, and one of the lead authors [of the NBER paper]. “Temporary measures have calmed the market but half of all US banks are running short of deposits with assets worth less than their liabilities, and we are talking about $9 trillion,” he said.

“They are bleeding capital and could not survive if something triggers a sudden loss of confidence. It is a very fragile situation and the Federal Reserve is watching it closely”….

Property developers must refinance their debts into the most hostile lending market in living memory, while falling rents and soaring insurance costs are eroding their revenue streams. Almost $1.5 trillion comes due by the end of next year.

A Long Island developer and New York Fed board member Scott Rechler described to Evans-Prichard that the best office space, so-called Class A buildings, were still holding their value, but there was carnage in the next tier, Class B and C. He remarked: “It’s stuff that’s competitively obsolete: side-streets, dark buildings. You can’t give them away.”

Understand the implications of distress in these lower-quality buildings. A restructuring might result in a 50% loss on the loan value. And the real estate indices that most investors rely on are slow to register price declines and here are understating them more by following only the prices of Class A space.

And you can’t fix problems like this with lower interest rates or emergency facilities:

More cheery information from Evans-Pritchard:

The paper estimates that 300 banks risk “solvency runs”. The trouble may not stop there: contagion could trigger “a widespread run by uninsured depositors, unravelling a fragile equilibrium in the banking system.”

The Fed and Treasury also believed that worked could be compelled to return to work, so that office rents would return to old-normalish levels. So the regulators are likely in denial about the severity of this slow-motion but very painful unwind.

So downside risk to banks is understated. But there are still enough in the way of wild cards to have much confidence as to how things will play out.

____

1 We do not have the time today to relitigate the matter of interest rate increases being the wrong remedy for the current inflation. The Fed has become the inflation first responder, which is the result of mission creep plus the Administration and Congress being derelict in its duty of managing the economy. A simple thought experiment for now: how will Fed interest rates cure the high price of eggs? Sanctions blowback? Worker shortages? Oh, ultimately the central bank can prevail by killing the economy stone cold dead….but that’s not a great idea. The failure of the Fed for decades to advocate for more countercyclical spending programs suggests it may be delighted to play an outsized role, even when it can’t perform it properly.

And as to broader Fed culpability: the central bank knew by 2014 (and contacts say even earlier) that its super low interest rate policy had become counterproductive. Yet Bernanke lost his nerve when faced with the so-called taper tantrum.

This has parallels with the sub-prime MBS situation back in 2007-08. Remember how AAA-rated mortgage bonds were “safe” until they weren’t? My memory is hazy and I am sure Yves will correct me here, but I believe it was because of the way the pools were constructed, some bad mortgages were mixed in kind of like a tiny bit of dog poop mixed in the cake.

It also seems unlikely that those class B and C owners won’t at some point compete to take business away from snooty class A owners. Sure, there will be clients like high powered law firms that will only want the best offices in town, on the penthouse level, to impress clients. But plenty of startups or tech firms can live with remodeled class B, if the price is right. Add some new carpet, an expresso machine, and a rent 50% lower than the LEED-certified palace downtown, and you might get tenants.

No, unfortunately you have this wrong. The subprime mortgage securitizations did not have other types of assets mixed in.

You are confusing subprime securitizations with CDOs, which were RESECURITIZATIONS.

4000-5000 subprime mortgages were put in a pool. Securities were issued against that pool. The AAA tranches (there were often more than one AAA tranches got ALL of the principal and interest (the two payment steams were separate) until they got what they were supposed to get, and then the monies went to the next tranche in line. The process was called a waterfall.

And the AAA tranches held up fairly well despite subprime being an infamous train wreck:

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3159552

The AAA tranches were popular since you got a higher than typical AAA yield.

CDOs were created to deal with the fact that the deal-packagers could not rip out all the fees they wanted and give all the potential investors high enough yields to get all the tranches sold. So they underpaid on the lowest rated tranche, typically BBB or BBB-. That was about 3% of total deal value. Sometimes the packagers could find suckers to buy them, but they were most often rolled into CDOs

Ah, thanks for the schooling. A lesson we may relearn. So maybe CMBS has a similar feature, but I have no idea whether the CMBS market works similar to the RMBS market.

I’ve worked in Class B and C buildings and the experience was awful. Most of us like nice things and nice places to work, compared to the alternative. Lots of businesses are having a hard time recruiting reasonably good workers. Recruiting them to work in crappy offices will be challenging.

I recall speculation here about the forces that kept NYC storefronts empty, and the hypothesis that lowering the rent would somehow trigger collateral increases or other unpleasant effects on the landlords’ loans, unlike empty units. As a result rent prices could not decrease to meet market conditions.

As great as the main piece is, I am even more impressed by the pithiness of the appended note which illustrates the grand delusion gripping simultaneously the Fed and the markets which hang on its every utterance — that somehow interest rate manipulation is a magic solution to every problem. It’s wishcasting as a substitute for thinking, the utility and credibility of which falls somewhere between that of a cargo cult and the Underpants Gnomes.

I just gotta say I love your coverage of bank stuff Yves, particularly when it’s combined with your unceasing sardonic tone.

Looking forward to how 2024 rattles this Jenga tower!

Of course, the next question is, will a renewed fiscal policy be restricted to only tax and spending cuts? Is anyone, these days, advocating for the opposite? Will ‘spend and tax’ ever become the accepted mantra. As Warren Mosler famously said, ‘you know, no matter how much I cut off it’s still too short”.

Good thing the Fed has prevented Americans from utilizing narrow banking. Wouldn’t want people to have any safe banking options.

The unnerving quality of an inflation is that no one knows anything for sure; how much his money is overvalued, how much of his prosperity is illusory, how much of his work is useless and would not even exist in conditions of stability. All standards are lost.

If there is any lesson to be learned from a study of inflations, it is that one never knows where he is in the midst of it, but he certainly is not where he appears to be.

Everyone loves an early inflation.

The effects at the beginning of an inflation are all good.

There is steepened money expansion, rising government spending, increased government budget deficits, booming stock markets, and spectacular general prosperity, all in the midst of temporarily stable prices.

Everyone benefits, and no one pays.

That is the early part of the cycle.

In the later inflation, on the other hand, the effects are all bad. The government may steadily increase the money inflation in order to stave off the later effects, but the later effects patiently wait. In the terminal inflation, there is faltering prosperity, tightness of money, falling stock markets, rising taxes, still larger government deficits, and still roaring money expansion, now accompanied by soaring prices and ineffectiveness of all traditional remedies.

Everyone pays and no one benefits.

That is the full cycle of every inflation.

As always, the inflation which comes later is blamed on every sort of extraneous event that happened to coincide in time with the later emergence of the hidden inflation. It is reminiscent of the difficulty primitive peoples are said to have perceiving the causal connection between last night’s ecstasy and next year’s childbirth.

Inflation is a policy choice because the government always has the theoretical ability to draw a line and say, “No farther!” But it is those “crises and catastrophes” that would ensue that lead everyone to believe that inflation is less bad than the alternative.

Make no mistake about this further fact: it is not a matter of child’s play, in fact it is not possible, to stop an inflation at any time without paying the price.

The price of past misdeeds is always there, is finite in amount, is usually greater than is thought, invariably rises still higher the more it is evaded, is ineradicable, will not go away, and in the end will be paid.

This goes back to an earlier lesson that the banks forgot over the years. Banks are NOT making risk free “loans” they are making INVESTMENTS.

Unfortunately, the middle class taxpayers will bail them out again. It’s not likely to be the rich bailing them out. The Tax Fraud Caucus will make sure the IRS lacks the money to enforce tax laws.

“The very fact that big banks cheekily are not putting away as much as they have been to cover for possible loan losses can be viewed as a sign of confidence”

the other way to look at it is like the 2008 scenario where the Amercan people, congress and the president had the proverbial gun placed to its head when the Financial thugs demanded their bail out. So now, those same forces are confident that they can do it again.

‘A sign of confidence that they will be made whole again’

That’s how a con-men play the con – isn’t it?

It’s been said a hundred years ago and it applies today like nothing has changed

“He isn’t really a big time crook unless you must let him alone to prevent the loss of public confidence.”

J.P.Morgan’s criminal convictions are legendary, yet the bank keeps getting bigger. Almost like the bank has some sort of special protection. / ;)

I drove by a number of condo and apartment developments that are “In Progress” today, including “The Cannery at Railroad Square” here in Santa Rosa.

The construction loans were made 2-3 years ago when rates were lower and they will soon need “Take out” or permanent financing at current rates.

Oops.

Those numbers no longer work leaving the developers two choices.

1) Delay the final touches because the construction loans don’t come due until a “Certificate of Occupancy” is issued, hoping that rates will drop soon enough that you avoid Bankruptcy and can still make a profit..

2) Declare Bankruptcy and hand the property over to the current lender or lenders.

There are quite a few properties in this situation in Santa Rosa and they are not small developments.

Construction lending is almost always done using floating rate loans tied to Prime or another index like 30 Day SOFR, so I surmise that the developers may already be under water just by virtue of the interest rate and building supply increases and ultimately unable to complete the projects.

Metropolitan public train use in Melbourne, Australia is down 32% below pre-covid. Mondays and Fridays down 40%, other weekdays ~33%. A good proxy for willingness of workers to commute into the city. Suggests a significant amount of office space underutilisation that will likely drive future space consolidations leading to more outright vacant space without leasees.

https://www.theage.com.au/national/victoria/how-covid-crunched-melbourne-s-public-transport-use-and-the-unlikely-winner-20240105-p5evg6.html

Workers are getting a productivity gain from technology at the cost of the capital class. Which is a good thing so long as the capital losses don’t get socialised.

Thanks for this post.

My comment is the same as it has been for a long time: Since the Clinton administration years, the Fed has been trying to reduce the number of banks and consolidate them into bigger and fewer banks. If small local and regional banks go under and their deposits are consolidated under a bigger bank, I think that would suit the Fed’s goals just fine. I hope I’m wrong, but I think I’m right. The Too Big to Fail banks keep getting bigger and bigger, not smaller and broken up. If I am right the Fed would see small and regional bank carnage as a plus, not something to avoid. / My 2 cents.

If it is not just NYC, but all big US cities than have survived the now ebbing population boom and the waste and pollution of the Cold War, then dilapidation is the problem, not the dark street. We have ignored maintenance, now called sustainability, for three generations at least. Profit based on endless growth was based on the absurd equation that profit=infinity. Which explodes like a comedy skit. Even Biden has suggested the obvious for stressed commercial real estate: convert it into low income multi housing units. And for the neglected old buildings that are too far gone, we need a new Deconstruction and Recycling Industry. All of this requires government subsidy, which after the pillage of the middle class and the impoverishment of the poorest, is merely paying a long overdue debt to society. Adequate housing and urban renewal. And that’s only one of many overdue debts to American society. If the zeitgeist really is renewal, as it should be, it also must fit a new sustainability model. Which brings me to the recent revelation that the SEC is construing a new investment category called the NAC-natural asset company. I think this is obviously a financial solution to resolve stranded assets by turning them into a conserved natural commonwealth (the value of which we can simply fiat), call it a Conservation Fund which cannot be spent but only used as collateral. With the requirement that every investment it backs must serve to repair the environment and society and that any profits must all be invested in kind. So that these “assets” are self perpetuating and as exponentiating as debt and pollution now are. No changing lanes. A strictly limited fungibility based on sanity and survival. Basically.

You might want to think twice about the so-called NAC Natural Asset Class stocks.

Beware the SEC’s Creation of ‘Natural Asset’ Companies

https://www.realclearmarkets.com/articles/2023/12/01/beware_the_secs_creation_of_natural_asset_companies_996044.html

and earlier from Whitney Webb at Unlimited Hangout:

Wall Street’s Takeover of Nature Advances with Launch of New Asset Class

A project of the multilateral development banking system, the Rockefeller Foundation and the New York Stock Exchange recently created a new asset class that will put, not just the natural world, but the processes underpinning all life, up for sale under the guise of promoting “sustainability.”

https://unlimitedhangout.com/2021/10/investigative-reports/wall-streets-takeover-of-nature-advances-with-launch-of-new-asset-class/

This Natural Asset Company idea sound very much like the old enclosure acts, take from the commons to give/sell to the wealthy. / ;)

From the Unlimited Hangout article above:

Though described as acting like “any other entity” on the NYSE, it is alleged that NACs “will use the funds to help preserve a rain forest or undertake other conservation efforts, like changing a farm’s conventional agricultural production practices.” Yet, as explained towards the end of this article, even the creators of NACs admit that the ultimate goal is to extract near-infinite profits from the natural processes they seek to quantify and then monetize.

adding also from the same link:

Both the NYSE and IEG have marketed this new investment vehicle as being aimed at generating funds that will go back to conservation or sustainability efforts. However, on the IEG’s website, it notes that the goal is really endless profit from natural processes and ecosystems that were previously deemed to be part of “the commons”, i.e. the cultural and natural resources accessible to all members of a society, including natural materials such as air, water, and a habitable earth. Per the IEG, “as the natural asset prospers, providing a steady or increasing flow of ecosystem services, the company’s equity should appreciate accordingly providing investment returns. Shareholders and investors in the company through secondary offers, can take profit by selling shares. These sales can be gauged to reflect the increase in capital value of the stock, roughly in-line with its profitability, creating cashflow based on the health of the company and its assets.”

—

my comment: What’s the WEF’s talking point? “It’s 2030 and you will own nothing.”

I agree this is scary. Uncharted territory given the approval of the SEC. I’d feel more comfortable if the details on expected “profits” were given an open forum. Profits earned from natural assets have traditionally been outright extraction. Followed closely by profiteering on them by making them, the actual assets/collateral, into commodities. These new Natural Asset Companies will have to prevent commodifying all their valuable collateral in order to maintain their license to “own” them. We need a new word for a form of gain from these assets that actually makes them something like token assets so that it doesn’t become the same old plunder. The SEC could construe a recycle-restore-replenish requirement. Or stg like that. With teeth. I think it’s unsettling, but it could be the start of good conservation.

really you can’t fix stupid. service was a spinoff of manufacturing. bill clinton and his country club GOP allies free traded away 200 years of america manufacturing wealth, skills, machinery, factories, unions etc., and gutted the new deal so that wall street parasites can make more quick bucks.

so lots of empty factories, gutted supply chains and gutted value added, lots of unemployment and poverty was the results, and the dim wits thought that cheap money and service would carry the economy.

my thoughts are that even with the work at home scenario, many of those lesser tiered buildings would still be viable, because after all, the banks were part of the service industry and service was part of the supply chains.

maybe not as valuable as before, but still valuable.

what we are witnessing is this, the liquidation of the american economy.