Yves here. This paper provides yet another lens into the deterioration of civic values in the US and the more-related-than-you’d-think difficulties the US is having meeting military recruitment goals, In the UK, there’s a solid correlation between per capita WWI losses in the UK and various pro-social activities….including enlistment for WWII. The authors posit a big reason for that outcome is that these communities, and the country as a whole, commemorated the loss of these young men in war.

When I was in Australia, I was struck at how serious (in the early 2000s) Anzac day was, even though the underlying event was a close to a debacle. From Wikipedia:

In 1915, Australian and New Zealand soldiers formed part of an Allied expedition that set out to capture the Gallipoli Peninsula to open the way to the Black Sea for the Allied navies. The objective was to capture Constantinople, the capital of the Ottoman Empire, which was an ally of Germany during the war. The ANZAC force landed at Gallipoli on 25 April, meeting fierce resistance from the Ottoman Army commanded by Mustafa Kemal (later known as Atatürk).[8] What had been planned as a bold strike to knock the Ottomans out of the war quickly became a stalemate, and the campaign dragged on for eight months. At the end of 1915, the Allied forces were evacuated after both sides had suffered heavy casualties and endured great hardships.

The entry continues to describe how the campaign became a defining event for both young nations:

Though the Gallipoli campaign failed to achieve its military objectives of capturing Constantinople and knocking the Ottoman Empire out of the war, the actions of the Australian and New Zealand troops during the campaign bequeathed an intangible but powerful legacy. The creation of what became known as an “Anzac legend” became an important part of the national identity in both countries. This has shaped the way their citizens have viewed both their past and their understanding of the present. The heroism of the soldiers in the failed Gallipoli campaign made their sacrifices iconic in New Zealand memory, and is often credited with securing the psychological independence of the nation.

Similarly, as many readers know, Russia continues to honor the memory of the very many who died in World War II via “Immortal Regiment” ceremonies.

By contrast, with the Iraq War, the US started trying to pretend our conflicts had no human cost. I recall military families being upset that videos of soldiers returning home in coffins suddenly were verboten on TV, when in the past these sacrifices were honored.

By Felipe Carozzi, Associate Professor of Urban Economics and Economic Geography in the Department of Geography and Environment London School Of Economics And Political Science; Edward Pinchbeck, Birmingham Fellow, Birmingham Business School University Of Birmingham; and Luca Repetto, Associate Professor Uppsala University. Originally published at VoxEU

Countries currently involved in active warfare – Ukraine, Russia, and Israel most prominently – have launched intense mobilisation campaigns to expand their armies. This column examines what compels ordinary men and women to fight. Specifically, the authors study how the memorialisation of British soldiers who died in WWI affected civic capital in the communities they came from, and whether that spirit shaped the behaviour of soldiers in WWII. Subsequent generations of soldiers from those communities were more likely to also give their lives in battle, and to be commended with military honours.

Data from the Uppsala Conflict Data Program indicate that 2022 was the year with the largest number of fatalities in state-based conflicts in over three decades. According to the Global Peace Index, produced by the Institute for Economics & Peace, the world has become progressively less peaceful over the last 15 years. Countries currently involved in active high-intensity warfare such as Ukraine, Russia, and Israel have launched intense mobilisation campaigns to expand their armies with fresh recruits. What motivates these men and women to fight, to take often fatal risks on the battlefield?

The actions of individuals in war pose a paradox for social scientists, especially for economists. Combat represents a topical example of a collective action problem, whereby most benefits from fighting accrue to a third-party – for example, the nation – while costs fall squarely on those who fight, particularly those who die (Campante and Yanagizawa-Drott 2015). It is therefore hard to rationalise the behaviour of soldiers in battle as motivated by pecuniary cost/benefit calculations. Yet, nations have long found individuals willing to engage in combat. A series of recent papers in economics and political science attempt to understand what motivates them to fight. Studies have focused on different drivers such as propaganda (Barber and Miller 2019), religious and cultural beliefs (Beatton et al. 2019), public recognition (Ager et al. 2021), and state repression (Rozenas et al. 2022), among other factors.

In a recent discussion paper (Carozzi 2023), we turn to this question by studying how past deaths in combat affect a community’s values and, through those values, how they shape combat motivation for the next generation of soldiers. Specifically, we study how the deaths of soldiers who fought in WWI affected civic capital in the communities these soldiers came from and, through this effect, shaped the behaviour of soldiers in WWII. For this purpose, we conduct an empirical analysis that focuses on the British experience in the two World Wars.

Great War Remembrance in the UK

Over 700,000 British servicemen died fighting in WWI, making it by far the deadliest war in the long history of the British Army. This severe shock triggered a wave of commemoration and remembrance that became a characteristic feature of British life to this day. A day of remembrance, instituted in 1919 to commemorate the Armistice of 11 November 1918, has been celebrated every year since with parades and ceremonies. The ceremonial laying of wreaths at the Cenotaph in Whitehall on Remembrance Day 2022 was one of the first public acts of King Charles III after his coronation. It is around this Remembrance Day that the Poppy Appeal is still held annually, with over 30 million of the well-known commemorative poppies produced by the Poppy Factory each year.

In Great Britain alone, over 50,000 war memorials were built after WWI (IWM 2024). These monuments can still be found in towns and villages throughout the country and were often built using funds raised by local communities. They serve as tangible symbols of the sacrifices that community members made in the war and call new generations to exhibit similar behaviour (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Message in Southern Hospital Great Hall, University of Birmingham

Notes: Birmingham University First Southern General Hospital WWI Memorial Plaque, ref no. WMO/236786.

Great War Deaths, Local Communities, and Battle Motivation in WWII

We can use the context presented by the UK in the first half of the 20th century to explore whether sacrifice in past wars has lasting effects on local communities by changing the behaviour of subsequent generations. We ask both if sacrifice in WWI had an impact on civic capital in the interwar period, and if these deaths affected the actions of the next generation of soldiers in WWII. Our hypothesis is that past acts of sacrifice and their commemoration can affect combat motivation because they foster values that encourage and normalise pro-social behaviour. That is, people raised in communities in which past generations are commemorated for their self-sacrifice will develop a set of values that emphasise collective action, and this will affect their behaviour. Building on previous work (Guiso et al. 2011), we refer to these shared prosocial values as ‘civic capital’.

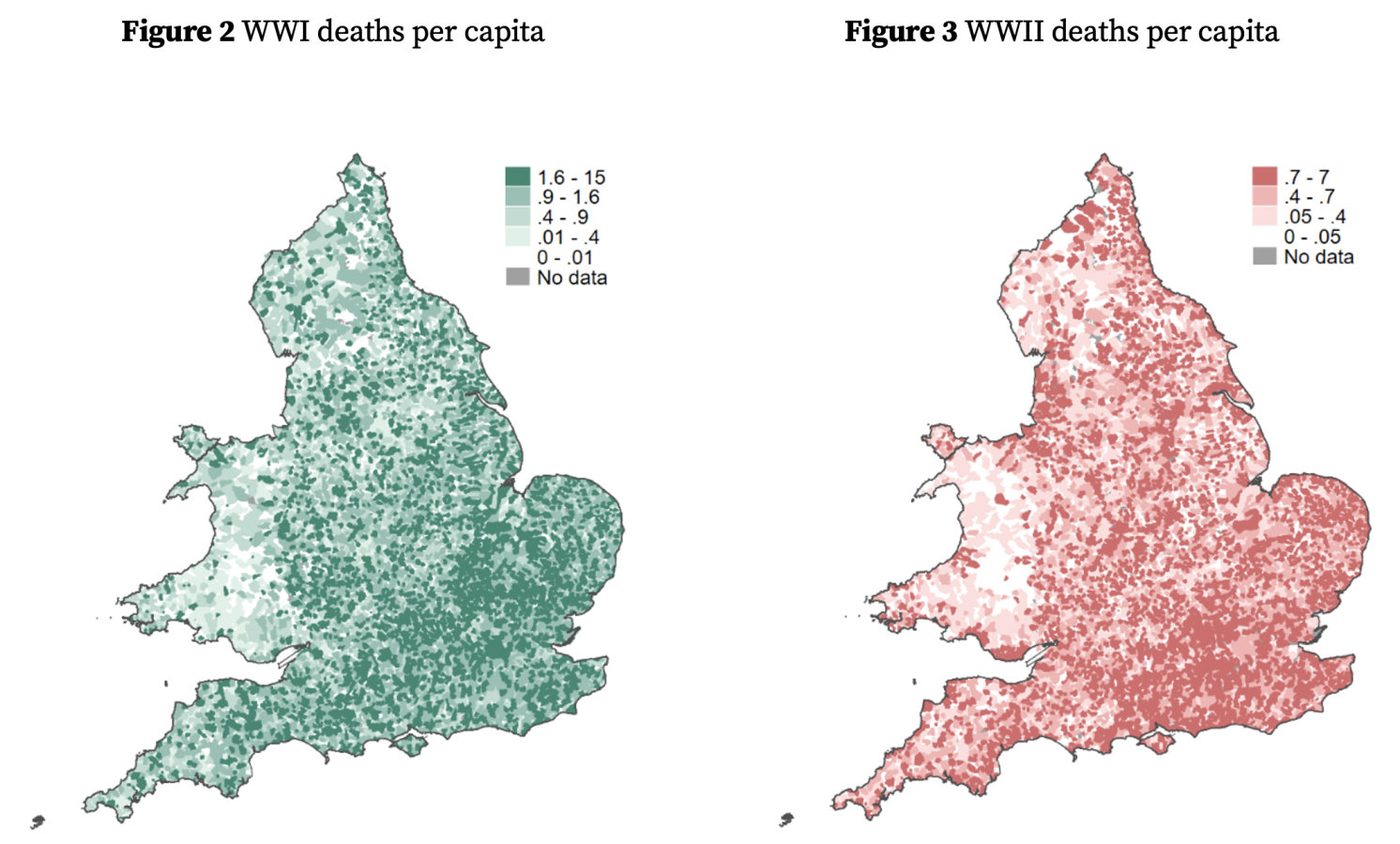

To test this hypothesis, we built a database combining information from individual-level WWI and WWII records on mobilised servicemen and deaths during the war. We geolocate these records to individual parishes of origin and use these parishes as our unit of observation in much of the analysis. For the sake of illustration, Figures 2 and 3 represent deaths per capita in WWI and WWII, respectively. We can observe that there is substantial between-parish variation in death rates in both wars. The same can be said about mobilisation rates in WWI (not shown).

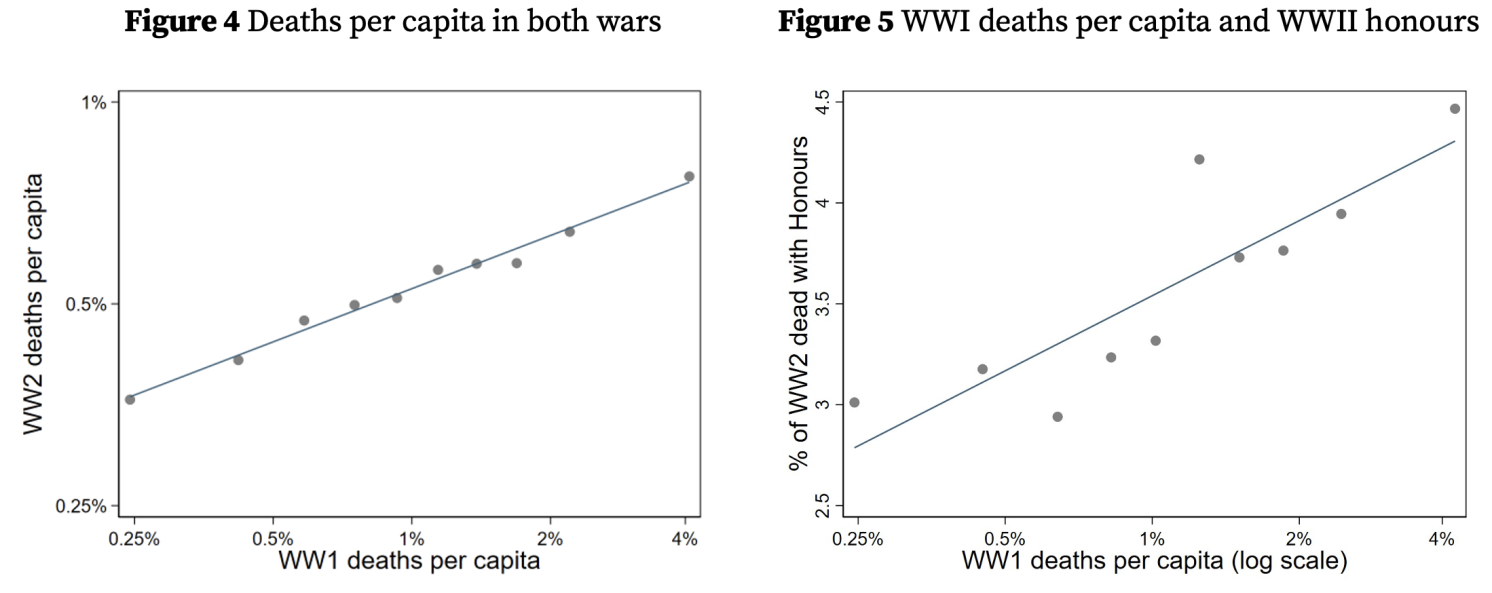

The first major finding in our empirical analysis is that community-wide soldier deaths in WWI strongly predict a community’s losses in WWII, as well as the likelihood that local soldiers are awarded gallantry medals in that conflict (see Figures 4 and 5). Critically, we use a shift-share instrumental variable strategy to establish that these connections are causal and not being driven by inherent, pre-determined social and economic characteristics of communities or their residents, such as their health status, income levels, or cultural factors.

We then use different measures of civic capital at the local level to study the role played by the transmission of prosocial values in explaining the observed changes in soldier behaviour during WWI. Because measuring a community’s civic capital is characteristically difficult, we use different outcomes as proxies for this (largely unobserved) variable in the interwar period: the creation of charities, the establishment of British Legion branches, the building of high-quality memorials (as measured by Listed status), and election turnout rates. We find a positive and significant effect of WWI deaths on all of these outcomes, lending support to the notion that a community’s sacrifices during WWI led to an increase in civic capital. Using tools borrowed from the mediation literature, we show suggestive evidence indicating that it is this process of civic capital accumulation and transmission that explains the results relating WWI deaths with WWII behaviour.

All told, our results strongly indicate that deaths taking place during a war, and their remembrance by subsequent generations, can be powerful determinants of value formation and future combat motivation. Our findings have several implications. They indicate that the experience of past wars can complement other forms of public effort to increase morale, such as propaganda campaigns or public recognition of actions in service. A darker interpretation is that war begets war by increasing the resources available for future conflicts. Because cultural transmission operates – at least in part – through local networks, this also implies that the human costs of conflict can become concentrated in particular locations, even if the locations themselves are not part of the battlefield.

The extent to which the legacies of past wars still influence British communities remains an open question, and exploring the enduring effects of war deaths is an ongoing focus of our research efforts. Equally, the extent to which these results can be generalised to other contexts remains unclear. If indeed the British experience in the first half of the 20th century is somewhat representative of broader patterns, this means that current conflicts will shape the values of communities that survive those conflicts and influence the combat motivation of future generations. We hope to explore these issues in future work.

See original post for references

I am really surprised that people are surprised that some countries are having difficulties in recruiting more cannon fodder for their empire’s glory and the elites’ benefits. Yes, past service by past

generations in previous wars do have a correlation to future generations’ services in their countries’ wars, but the specific reasons for a war and just how mutual both service and risk are also influences a nation’s willingness. Note, that is a nation’s willing service to its country, which usually means its ruling government.

I see precious few of our ruling “elites” willing to risk their sons and daughters for their families’ investment portfolios, but they all seem just fine for the children of the poor and working classes to do so. It is just like with the trades or factory work, which is considered work done by the unworthy, the foolish, and the expendable, to shipped off to China or done by semi enslaved imported labor. And it seems fine with my local elites for people to live and die in filth out on the streets or the bushes and trees.

It would be nice to be proud enough of my country that the idea of serving it would not seem so ridiculous. Well, for the American nation or people, it is not. Even its putative ideas, but the country, that ghoulish empire? Well…

Of course past wars shape a country’s values. But it’s all about what remembrances get priority. Walk by the inscription in figure 1 every day, and you might get the idea that wars are somehow necessary and virtuous.

But if you start having too may people quoting Kipling (an elite who lost his son to WWI, back when the sense of noblesse oblige still existed to some extent at least) –

“If any question why we died

Tell them, because our fathers lied.”

– well, then you see how recruitment might begin to suffer.

If one looks at some of the myths propagated in the USA, it is easy to see why the elites behave as they do.

Iraq/Afghanistan war launching George W. Bush avoided the Vietnam war while he was flying stateside in the USA for the air national guard, Dick Cheney had multiple deferments to avoid Vietnam, Connecticut Senator Richard Blumenthal was willing to allow the story that he “served in Vietnam”, while stateside, be propagated for years

Yet John Kerry’s actual Vietnam service was denigrated by the Republicans.

Then there was super patriot, actor John Wayne, who avoided serving in WWII, but acted in numerous war based movies.

Wayne even got an airport named after himself.

Meanwhile, baseball star Ted Williams interrupted his baseball career for five years to serve in both WWII and Korea .

Chicken Hawks survive and encourage others to fight for “democracy”, “freedom” or “rules based order”

Elite control of the media helps the USA population remain complacent..

I have a relative who recently enlisted in the USA army.

He mentioned that one of his fellow enlistees described his prior position before enlisting as “homeless”.

At a televised press conference, Fico of the Slovak Republic has come out in support of Orban/ Hungary.

https://twitter.com/MyLordBebo/status/1749340805863510244?t=1vtMJ16QwfZ8F_fzWtskag&s=19

Fico of the Slovak Republic has come out in support of Orban/ Hungary.

I follow closely that call for the withdrawal of the voting rights of an EU member state. I can tell you very clearly that as long as I am the Prime Minister of the Slovak Republic I will never agree to punish a country for fighting for its sovereignty and national interests whether it is within the framework of national programs or within the framework of the European Union…

[ I immediately found this a most impressive and hopeful position; relatedly, I found the academic and editorial attacks on Hungarian sovereignty in the US to be a distressing disregard of Hungarian national integrity. ]

Similarly, the problem of George Soros in Hungary was that Soros came closer and closer to dismissing Hungarian sovereignty as the Hungarian government resisted taking increasingly aggressive stances towards Russia. Soros was not interested even a fig in Hungarian democracy, but in foreign policy control.

Of course, the same was evident for a number of foreign – American and British – NGOs in Hong Kong.

There are some good points in this article, though I have to question why hasn’t the author considered the effect of recent “successful wars” from the perspective of the US and UK i.e. Granada, Panama, the Gulf, Serbia, and the Falkland? Was there any noticeable increase in recruitment intake following these wars? I know how quickly forgotten they were made to be, but during their time they were widely broadcasted and used in propaganda efforts. I know veterans who enlisted in the US Army during the 90s, and from what they said even after the 1st Gulf War the army still had this stigma as the place to go for kids who didn’t know what to do with their lives. It was only after 9/11 that you began seeing enthusiastic volunteers.

Secondly, I really don’t know if the commemoration of Poppy Day was that big during the immediate aftermath of WWI and WWII. Ever since I was born until now, the boomers have always been the most enthusiastic participants in all the hubbubs and virtue signaling. The favorite hobby of columnists in this country is to evoke the blitz, something that they definitely have not lived through. It’s almost like they are trying to gain points with their late fathers and mothers, who were deeply traumatized by the war.

This was not a thought exercise. It was a data exercise. The study took advantage of potentially informative data. I doubt you could construct anything like it for the US. The Falklands was too small to have any societal impact, IMHO.

Recognizing why Russia remembers their dead from WWII is important: it lost approximately 30% of its population. In contrast, the US lost ~0.25% of its population. For the US the war was mostly a disruption to their ongoing lives (for women an opportunity to enter the workforce).

When was the last Veterans parade in the US? In Russia their remembrance day is a huge social event.

We did commemorate World War I and World War II dead. Veteran’s Day parades used to be important and the men who’d fought in those wars marched proudly. In the library of the Jewish Community Center in Birmingham, they have painted portraits of each of the seven young men who died in World War II.

Yet another study that purports to explain ‘social’ issues without reference to class! Except for the slightest (sleight?) of hand-waves:

> [W]e … establish that these connections are … not being driven by inherent, pre-determined social

> and economic characteristics of communities or their residents …

In the US, it is commonly recognised that a disproportionate number of military personnel are from the South. As Yves noted in a response yesterday, people enlist in the military because they are poor. Last I looked, as a region, the South had a higher prevalence of poverty than other parts of the country.

Also, the authors of this paper are not especially careful about details.

> The ceremonial laying of wreaths at the Cenotaph in Whitehall on Remembrance Day 2022

> was one of the first public acts of King Charles III after his coronation.

Was perhaps Remembrance Day 2022 delayed because of the corona or for some other reason? Otherwise, HRH must have employed the Royal TARDIS, since his coronation was on 6 May 2023.

Did you miss that this study was about the UK?

Oh, and one of the noteworthy features of the Great War in the UK was the degree to which boys from aristocratic families enlisted? It was assumed the war would take only weeks and these scions wanted to tell their girlfriends and young brides about the exciting experience of battle. If you knew anything about the UK of that era, you would know that.

In other words, stop Making Shit Up. You are earning demerits.

Gunna have to say that I am not a fan of this study as it lacks context. And a study that lack context is no study. So let’s look at a few countries mentioned here. First, Oz-

‘According to the First World War page on the Australian War Memorial website from a population of fewer than five million, 416,809 men enlisted, of which over 60,000 were killed and 156,000 wounded, gassed, or taken prisoner. The latest figure for those killed is given as 62,000.’

Every family here had lost someone to the war or knew personally someone that had been killed. A remarkable fact was that they were all of them volunteers. Twice the government tried to push through conscription but were defeated in two referendums. How did it effect recruitment in WW2? Hard to say as after Pearl Harbour, it became an existential fight to the finish and everybody got called up that could.

With the UK you have the same thing. Whatever the recruitment numbers, after the Fall of France it became an existential fight as it went on to a total war system. They knew full well what a German invasion would be like. I should note one thing here. I have read accounts by people that were in Germany, France and England when war broke out in 1939. None of them talk about cheering crowds or mass celebrations like in 1914 as they knew war only all too well and knew what was coming. Which brings me to France. I think I read that there was a reluctance to join up for war in 1939 which is not surprising. In WW1 the French army suffered around 6 million casualties, including 1.4 million dead and 4.2 million wounded – roughly 71% of those who fought – out of a population of less than 40 million people. That is colossal that and explains no rush to arms in 1939. To put that in context. the US lost “only” 116,516 people in WW1 out of a population of about 100,000. And yet it was enough to promote an Isolationist Movement in the 1930s that only died after Pearl Harbour. Adjusting the French experience to the US, how would that country have developed if it had some 15 million casualties in WW1?

And this brings me to Russia and the Ukraine. For Russia, they can see that the present war is an existential one and so recruitment is far more than expected. They see how the west tries to economically destroy their country and adopted a rabid racism that cancelled Russian culture, accomplishments, arts, music, dogs, trees – in fact any and everything that was Russian. So they are in no doubt what this war means and hearken back to their grandparents in the Great Patriotic War. We have seen how Ukrainian recruitment has went and the extreme reluctance to go to the front. It is not that they are not willing to fight for their country but they see how their lives are being senselessly squandered in meaningless attacks. So people are kidnapped off the streets as fresh meat and just this week I read of one young Ukrainian soldier’s funeral where the Commissars turned up and gave out conscription notices to mourners. So as I said, it is all a matter of context as without it, you ain’t got nuthin’.

Oops – I mistyped. The WW1 population of the US was about 100,000,000. And of those 116,000 that died, less than half was in actual combat.

Until WW2, the majority of soldiers died of disease, not wounds. Without the Spanish Flu, this number would probably have tilted in WW1.

The story of combat was that the winner was usually whoever managed to get his soldiers onto the battlefield before they died on the road.

“Amateurs talk tactics, professionals talk logistics.” It really is true, always has been.

The original discussion paper is behind a paywall, so I’m left to wonder if the British regimental system led to regiments usually recruiting from the same (regimental “home”) area thus instilling a certain esprit de corps to the civilian population. As in “me grandad was a volunteer in the Duke of Lancaster’s Yeomanry in the Boer war, me dad was a volunteer in the Duke of Lancaster’s Yeomanry in the Great War, and I shall now volunteer the same to show that Mr. Hitler what’s what”.

When my granddad was conscripted in the 1920’s, the Army in this corner of the globe was aiming to maximize the unit cohesion by constructing units on the base of municipalities. The idea was that men who already knew each other from the school and often had worked together in civilian life basically were already used to pulling together.

The war, when it came, then showed the concept to have a big, big weakness. A one battle gone bad could wipe out a huge portion of the working age male population of a single village – and that was not good for the morale either in the front or in the home. Within 6 months in the real war the system was changed to more “casualty aware” distribution of the rank and file.

On an anecdotal level, but related to the article: my granddad fought 3 years in WW2 and never spoke about it – except when any of his grandsons left to do the compulsory military service he had some personal anti-war story to tell. Only decades after his passing did we manage to find out the units and battles he had been in.

Your description of how the British Army recruited in WW1 is a damn good description of how it worked. Since the Cardwell reforms of the 1870s, each region had a Regimental Depot (e.g. that for the South Wales Borderers was in Brecon, Wales) and entire battalions were recruited from these regions. Then you had the “Pals battalions” which kept up until the Battle of the Somme and the massive casualties showed the folly of this approach-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pals_battalion

One of the most horrible things about recruitment from back then I read about was this football match in northern England. A titled Lady stepped forward and each man that signed up received a kiss from her and quite a few were recruited. It was probably only after they reached France that they discovered that it was more of a mafia kiss.

here is the original paper from LSE in PDF format for free: https://cep.lse.ac.uk/pubs/download/dp1940.pdf

” my granddad fought 3 years in WW2 and never spoke about it – except when any of his grandsons left to do the compulsory military service he had some personal anti-war story to tell. Only decades after his passing did we manage to find out the units and battles he had been in.”

This was my experience as well. PTSD was probably more prominent then but not recognized as such. ( it was shell shock). And, they went through much more horror than those did in later conflicts.

A great find, thank you, Yves, for the article. The experience of war and/or brutal occupation deeply affects the psyche of people for generations to come. Below are a couple of examples of how, to this day, it is possible to see the impact of the war in different parts of the UK.

8th May (VE/Victory in Europe day) is not marked by any significant celebration in the UK. However, the Channel Islands, the only part of Britain that was under the German occupation during WW2, made the 9th of May (Liberation Day) a national holiday and everyone, young and old, irrespective or religion and interests is celebrating the Liberation Day. Suffering experienced under the occupation is not forgotten and the memories and stories of occupation are passed on to future generations. To the Channel Islander the end of WW2 is a more significant event than to the average person residing in another part of the UK.

WW2 shook up the UK nation and brought about policies to improve the lives of British people – The Beveridge Report and the birth of the National Health Service are some of the examples (https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/guides/zsd68mn/revision/3)

Generations of Soviets and their descendants were and are continued to be influenced by the experiences of WW2. The losses of WW2 and the memories of atrocities committed by the Nazi Germany on the territory of the Soviet Union are still fresh in the psyche of people living in former USSR. It would be difficult to find a single family in former USSR that has not lost a close family member during WW2. There are still quite a few living survivors of the Siege of Leningrad who have children, great grand children. This could be one of the reasons why Russians have united so quickly under the external threat and the support for Putin went up after the events in Ukraine. The memories of WW2 are still fresh in former USSR republics.

A recent jump in Stalin’s popularity of Stalin could be attributed to the WW2 scars carried by the generations of descendants of Soviets who lived through the horrors of WW2.

https://www.rferl.org/a/stalin-s-appeal-surging-among-russians-opinion-poll-suggests/29884485.html

https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2021/07/23/why-is-stalins-popularity-on-the-rise-a74565

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liberation_of_the_German-occupied_Channel_Islands

http://www.germanoccupationmuseum.co.uk/

I find it unsurprising that those parishes that had fewer war deaths per capita (mostly in Celtic Wales) founded fewer charities for war widows and war orphans. I can believe that those parishes were also ‘pro-social’, but in a different way.

It should be noted that one of the chief proponents of Gallipoli was First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill.

What brought down Neville Chamberlain and made Churchill Prime Minister in 1940 was the abject failure of the Norway Campaign, which was run by Winston Churchill.

Seriously, Churchill failed up so many times, and had one good day.

He resembles Rudolph Giuliani without the bad hair dye.

An interesting anecdote from the 60s/70s.In our little mining town in the Forest of Dean,virtually each week one would read in the local paper when some young some young tyke was up on a misdemeanor (possibly the latest of many) his solicitor would say “He’s off to join the regiment your honour” In our case ‘The Gloucesters’.

Most of the men on our war memorial were in The Gloucester’s.

The war memorials in all those little villages,towns etc. throughout the UK will be linked umbilically to their local regiments.Which I guess reinforces the above article.However,very few British regiments of the line remain -the Gloucester’s were amalgamated many years ago.Thus greater efficiency broke the

local chain of mates growing up,fighting and dying together.A chain with hundreds of years of local history.

This I guess is possibly a small reason for current recruitment problems.

An anecdote from the 60/70s.In our little mining town in the Forest of Dean the local paper would publish the cases in the local Magistrates Court.

Each week invariably some local tyke up before the magistrate (possibly not for the first time) would be defended by his solicitor with the explanation.” He’s off to join the regiment your honour” In our case the regiment was The Gloucester’s.This plea was virtually always accepted.

Most of the servicemen on our memorial were in the Gloucester’s.This holds I suspect also for the whole of the UK and possibly other countries.where pride in the local regiment was paramount.These lads grew up,fought,and died together often in very large numbers.

Greater efficiency killed the regimental system and the Gloucester’s with most other regiments are long long gone.One small reason perhaps why recruitment is more difficult now.Hundreds of years of history for some little villages now a folk memory with every Armistice day now a nightmare of jingoism.