Yves here. The press has been reporting on more and more extreme weather events, not just unusual heat but also torrential rains that dramatically flooded Dubai. That’s on top of atypically wet weather that wrecked UK crops. Without giving a catalogue, it’s becoming clear that more and more residences and livelihoods and therefore communities are at risk from climate change.

The Pentagon had the geopolitical impact of climate change on its radar in the early 2000s. One of the early concerns was sea level rises producing mass migration out of particularly vulnerable countries like Bangladesh. But as this article describes, climate migration has already come to the US and is set to increase.

By Jeff Masters. Originally published at Yale Climate Connections

limate-driven migration has already begun,” writes climate journalist Abrahm Lustgarten in his must-read book, “On the Move: The Overheating Earth and the Uprooting of America.”

“In the United States,” he continues, “a quiet retreat from the front lines of Western wildfires and Gulf Coast hurricanes is hollowing out small towns. These are the subtle first signals of an epochal slow-motion exodus out of inhospitable places that will, as the climate warms further over the lifetime of today’s children, unfold on a global scale.”

If you’re looking for a book that can help inform your personal choices on how to prepare for the future of climate change in the U.S., Lustgarten’s book is the best one I’ve seen yet. “On the Move” begins with a four-chapter overview of the tremendous pressure climate change is placing on us, using the latest scientific findings combined with interviews with some of the key scientists involved. It describes the shortsighted policies that have encouraged risky development in vulnerable areas, as well as how decades of economic policies have favored some Americans over others, leaving Black and poor communities in the most danger as the climate warms.

If you’re looking for a book that can help inform your personal choices on how to prepare for the future of climate change in the U.S., Lustgarten’s book is the best one I’ve seen yet. “On the Move” begins with a four-chapter overview of the tremendous pressure climate change is placing on us, using the latest scientific findings combined with interviews with some of the key scientists involved. It describes the shortsighted policies that have encouraged risky development in vulnerable areas, as well as how decades of economic policies have favored some Americans over others, leaving Black and poor communities in the most danger as the climate warms.

The next three chapters follow the emotional arc of Americans being forced to move or potentially forced to move by climate change. Large communities are already beginning to shift, displacing many people, but many others are becoming trapped by poverty, age, or the economic decline of their communities. The final two chapters present the latest research on how many Americans might move and from where: a portrait of “American society transformed.”

What follows below are some of the highlights from “On the Move.”

Life Is Different Now

The book begins by presenting what life might be like in the U.S. because of the rapid onslaught of forced climate change-induced migration over the next 10 to 20 years. The first chapter, “Life is Different Now,” includes a moving account of how one family’s once-safe home in the California San Francisco Bay Area has been transformed into a dangerous place because of unprecedented wildfires in recent years. Their agonizing decision: Should they stay or should they go?

Throughout the book, Lustgarten, who also lives in a wildfire-prone portion of the Bay Area, describes his angst about experiencing the new climate change reality there: skies turned orange by smoke, the constant tension of being prepared to evacuate, rolling blackouts that ruin perishable food, and increased insurance rates. One chapter ends with his phone conversation with Tulane University’s urban planning and climate migration expert, Jesse Keenan, where Lustgarten asks him:

“Should I be selling my house and getting —”

He cut me off. “Yes!” came his emphatic reply.

An Eyewitness Account of the Desperation of Central American Climate Migrants

The most powerful chapter of the book tells the story of the author’s visit to Central America to understand international migration to the U.S. He visits desperate farmers who face a new climate where the rains don’t come on time, bringing droughts too fierce to grow the crops they used to be able to. They have no option other than to abandon their homes and seek a better life elsewhere.

Recent research confirms the link between an increase in Central American drought and migration to the U.S. According to a 2023 paper, “Dry growing seasons predicted Central American migration to the U.S. from 2012 to 2018,” “Unusual weather variability and unpredictable seasons has contributed to migration globally. We found 70.7% more emigration to the U.S. when local growing seasons in Central America were recently drier than the historical average since 1901.”

How Water Availability Can Lead to the Slow Abandonment of a Community

Another moving section of the book looks at how climate change can slowly degrade the quality of life in portions of the U.S. where water availability is declining. Lustgarten recounts his visit to the rural Eastern Colorado farming town of Ordway (pop. 1,100). Beginning in the 1920s, water from the Colorado River was diverted to irrigate Ordway, resulting in a financial boom. But as Colorado’s nearby cities grew and the climate grew hotter and drier, water became more scarce and more valuable, resulting in a major move for residents to sell their water rights and leave the farming business. As a result, Ordway suffered a “fast-forward” version of how climate change might affect places with water scarcity in the non-too-distant future. Lustgarten writes how the town has “essentially turned into a desert”:

The water sales made the county and its farmers more dependent than ever on the temperamental rains of the prairies, just as climate change began causing a long-term decline in the state’s overall water supply. After the water sales, thousands of acres of farmland dried up almost overnight. One by one, people shuttered their farms and moved. The dealerships closed; the tractor store went belly-up. Without enough produce to can or beets to process, the factories closed, too. Then, without goods to ship, the railroad went away. Then people began to slip away, too. Of the 65,000 acres once farmed here, just 1,500 still produced crops. Empty fields extend for miles, patches of raw ground filled with tufts of weeds. Even the wildlife is gone. Few birds chirp. Nothing will grow because the soil is used up, devoid of nutrients. A merciless wind rakes across its surface, scouring the loose soil. Huge Dust Bowl-like clouds of sand blow in, making it difficult to see across the street.

The Shifting Human Climate Niche

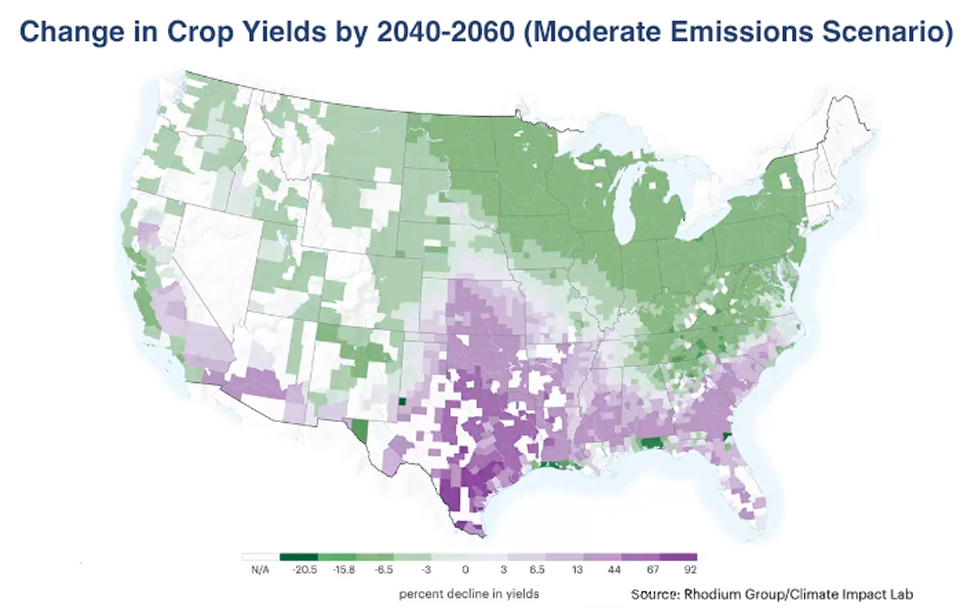

Throughout the book, Lustgarten intersperses a number of helpful maps from climate migration researchers. Many of these can be found at a 2020 article by ProPublica.org, New Climate Maps Show a Transformed United States. One particularly telling map shows the potential change in agricultural crop yields in the U.S. from climate change (Figure 3).

One researcher interviewed is Marten Scheffer, co-author of a 2020 study, “Future of the human climate niche.” The book includes three maps based on this paper displaying how the ideal human habitat in the U.S. will shift dramatically northward between now and 2070, even under a relatively modest climate change scenario. Lustgarten writes, “The map suggests that almost all of the southernmost latitudes of the United States, roughly following the Interstate 10 corridor from San Diego, California, to Jacksonville, Florida, are destined for enormous challenges as the climate continues to warm.”

Lustgarten describes how this paper shows that climate change is fundamentally shifting the human climate niche:

For at least 6,000 years, people have lived in places that offered a very specific and narrow range of moderate temperatures and modest precipitation — a human niche. What Scheffer and his colleagues’ research suggested was that while migration might have always taken place, conditions are now being created for a sudden and dramatic uptick in both its scale and pace. What they discovered was a picture of mass upheaval that will likely be the largest demographic shift the world has ever seen.

Conclusion

“On the Move” is a timely and important book on the climate change-induced mass migration that has already begun and that will fundamentally rock society. At the end, Lustgarten recommends a holistic approach to the great climate migration crisis that is already unfolding:

This means doing the hard physical work of defense: building sea walls to hold back the ocean and managing forests to forestall wildfires. But it also means investing in transit systems and sewer systems and discounted health care and subsidized child care, because each of these social investments builds up the strength of communities and families so that when climate shocks arrive, households are financially sturdy enough to withstand the change.

On the Move: The Overheating Earth and the Uprooting of America (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2024) is $14.99 on Kindle at Amazon.com and $23.17 in hardcover.

Related reading

This is part one of a two-part series. Part two will look at the book’s portrayal of the challenges facing Atlanta, which may be the destination of over a million climate migrants this century.

For those wanting to learn more about climate change migration, another great book is “The Great Displacement” by Jake Bittle (my 2023 review here). I also recommend “Nomad Century,” by Gaia Vince, which argues that migration should be encouraged because it drives economic growth and reduces poverty. The author calls for a safe, fair process for migration, overseen by a global agency with powers to police it. Another recent book, which I did not get a chance to review, is “Planetary Specters.” It argues that to understand the systemic reasons for displacement, it is necessary to reframe climate disaster as interlinked with the history of capitalism and the global politics of race.

- Part one of my three-part sea level rise series: How fast are the seas rising?

- Part two of my three-part sea level rise series: Eight excellent books on sea level rise risk for U.S. cities

- Part three of my three-part sea level rise series: 30 great tools to determine your flood risk in the U.S.

- Bubble trouble: Climate change is creating a huge and growing U.S. real estate bubble

- ‘Where should I move to be safe from climate change?’

- Many coastal residents willing to relocate in the face of sea level rise

- Disasterology: a book review

- With global warming of just 1.2°C, why has the weather gotten so extreme?

- ‘Is it foolish to hold onto my family’s beloved waterfront home?’

Recommended reading:

- Susan Crawford’s awesome Substack feed on climate adaptation policy, Moving Day

Carbon Brief’s detailed 2024 report, In-depth Q&A: How does climate change drive human migration? - Gilbert Gaul’s 2019 book, The Geography of Risk

- Climate futurist Alex Steffen’s newsletter

Bob Henson contributed to this post.

I check this daily. Scary!

https://climatereanalyzer.org/clim/sst_daily/

Buy the f…ing ATH!

Love that bull rally from the 17th. Good technicals

The key central lesson of the past few years – and it will be a hard earned one – is that while climate models have proven very accurate and successful at predicting global and (sometimes) continental scale climate change, they are at a loss at predicting what really matters to most people – local and regional change. There are simply too many factors to consider. As one example, around 2 decades ago I was at a conference on climate change where someone asked the panel where they would move to if they wanted to protect their children. Most settled on the American/Canadian north west – one (semi-jokingly) said that the Seattle/Vancouver axis would be the new Venice Beach/Napa Valley in terms of liveability. But as we’ve seen, the impact of drought and forest fires would have made that a pretty bad move.

The message doesn’t always percolate down. I’ve been in meetings with engineers who calmly talked about ‘building in climate resilience by assuming a 30% increase in flood intensity’ as if this settled the question. When I’ve asked where that 30% figure comes from, they refer to model predictions. But when you ask the people who did the models, they will always tell you that figure is an overall average for a region – its impossible to predict what the impact will be on any one river catchment. A 30% average increase in rainfall over a region could well mean one catchment almost disappearing in drought, while the next catchment has a 100% increase in flood frequency/intensity.

So the only certainty is that we will have some very nasty surprises. Its also possible that we’ll have some pleasant surprises (right now, much of the Arabian peninsula is a beautiful shade of green due to unexpectedly good rains, one flipside of Dubai’s floods), but the nasty surprises will almost certainly outnumber the good ones.

One problem of course is that we are all tied up in ‘we should do X, not Y’ arguments on one topic or another. The core issue is that its way too late for any ‘one’ thing to work. Its not a case of reducing consumption drastically, or using technology to save us, or building in resilience to our cities/agricultural systems, or geoengineering. We have to do them all, and we have to do them quickly.

Geoengineering seems like one to avoid – not because it wouldn’t help if done effectively, but because it needs global coordination to be effective and we’ve pretty much conclusively demonstrated we’re incapable of such coordination.

‘The Pentagon had the geopolitical impact of climate change on its radar in the early 2000s. One of the early concerns was sea level rises producing mass migration out of particularly vulnerable countries like Bangladesh.’

There were other reasons why the Pentagon showed interest in climate change. It did not take long to work out that as the sea levels rose, that they would lose some of their most important US Navy bases to the rising tides and flooding of those base would become more and more frequent, not only in the US but in their overseas bases as well-

https://www.navytimes.com/news/your-navy/2016/07/29/rising-oceans-threaten-to-submerge-128-military-bases-report/

I know but not much has been done. And the land is subsiding along the east coast of the US in many places. So a double.

This site has addressed some of the issues, the problems that arise before inundation. Drinking water, flooding, sewage disposal all become issues, making habitation difficult.

But they did identify the problems, so you know. Can’t use Rumsfeld’s unknown unknowns. Seems increasingly apt, NK’s oft repeated “this is not a serious country.” I don’t know how else to describe it.

It might be that the ruling elites have already decided to treat America as a burndown. Lambert Strether has said that they regard America as a teardown. But a teardown implies a build-back of something new and different.

Whereas a burndown implies an end-goal of grabbing the insurance money and running to another country when the balloon goes up to burn the country down. For the insurance money.

If the mass majority of inhabitants decided to see the ruling elites for the burndowners they are, would the mass majority try to physically delete the burndowners from physical existence before the burndowners get the chance to finalise their Last Burndown and Last Thunder-Run with the insurance money they plan to grab on their way out?

I suspect the insurance companies would be the first out the door. They would NOT be left holding worthless properties.

I brought that up on a forum around that time, and got shouted down by the usual suspects. They were talking their book, or what they were paid to spout. Not much has changed although the methods have been updated for more FUD.

Recognizing bad-faith works of such groups, along with the varieties of persuasion techniques and counters thereto become even more important life skills, starting in the home and with school-age students.

Read it and HIGHLY recommend it!

“Anything south of I-10″…guess I’m safe. There have been stories about how the “halfbacks” who deserted the North for sunny Florida are now moving back north to Appalachian areas like mine. Ironically well watered areas such as upstate SC are turning farms into houses when that land may be needed to grow food once the West completely lapses into drought.

And it’s hard to feel sorry for those Colorado farmers who put communities where they were warned not to do so. Of course their forebears were likely poor people coming in covered wagons rather than alfalfa growers with hundred thousand dollar machines.

Which is to say the US has seen many migrations and was a country founded in part by real estate promoters like George Washington. In that sense not much has changed. One of them wants to be president again.

Ultimately this about the morality of climate change and its consequences. If the West retreats to building bigger AC while millions die from 35C Wet bulb temps then the immorality should be obvious. Nobody in Mali contributed to climate change. Besides that, if some people find themselves in precarious living circumstances it would be inhumane to let them die b/c they were born unlucky.

If the poor countries were populated with blond Swedish Lutherans they’d be welcome with open arms. And the West is tolerant compared to the Far East. It’s not an accident that JP and CN are extremely unwelcoming to non-Asian ethnics. Aging populations will force some agonizing re-appraisals by multiple countries.

At the risk of being flippant, may I say to my Aussie Bro’s, that New Zealand is looking better every day!

Its probably looking better to China, India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Indonesia, etc. every day too.