Yves here. As global conflicts seem way too likely to blow big, and US politics look, as Lambert would say, overly dynamic, the global warming train is not slowing down. Matthew Simmons and his peak oil confreres look to have called for a turn way too early. Needless to say, the projected continuing fossil fuel production levels are to the detriment of the environment and in due course, civilization as we know it.

Green energy projects, based on the neoliberal premise that letting people shop “smarter,” perhaps with tax incentives and disincentives and even mandating an end to new internal combustion car production, will curb fossil fuel use. The post explains that that is not expected to happen, at least not on anything resembling the timetable needed to prevent worst outcomes.

Contrast the post below with the recent peak oil consensus, oddly not updated in Wikipedia:

There was [when?] a consensus between industry leaders and analysts that world oil production would peak between 2010 and 2030, with a significant chance that the peak will occur before 2020. Dates after 2030 were considered implausible by some. Determining a more specific range is difficult due to the lack of certainty over the actual size of world oil reserves. Unconventional oil is not currently predicted to meet the expected shortfall even in a best-case scenario. For unconventional oil to fill the gap without “potentially serious impacts on the global economy”, oil production would have to remain stable after its peak, until 2035 at the earliest.

Now admittedly, the post is talking about oil demand, not supply, but there seems to be no concern that the spice will still flow.

By Alex Kimani, a veteran finance writer, investor, engineer and researcher for Safehaven.com. Originally published at OilPrice

- Whereas the short-term oil price outlook appears murky, leading oil agencies remain largely bullish about the long-term outlook.

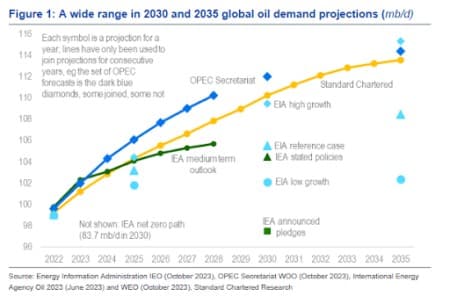

- Interestingly, over the medium-and long-term, only the IEA sees global oil demand peaking before 2030.

- Standard Chartered has predicted global oil demand will hit 110.2 mb/d in 2030 and increase further to 113.5 mb/d in 2035.

The oil price rally has lately lost some steam, with WTI for May delivery and June Brent futures slipping more than 5% since Friday after the Energy Information Administration (EIA) released bearish weekly data that triggered demand concerns. According to the EIA, crude inventories rose 5.84 mb w/w and oil product inventories rose 6.57 mb; however, the builds relative to the five-year average were modest, at just 0.11mb for crude oil and 1.24mb for products. U.S. commercial inventories now stand 16.47mb below the five-year average, with crude inventories at Cushing 7.35 mb below the five-year average. The EIA also estimates U.S. crude oil output clocked in at 13.1 mb/d for a fifth consecutive week, 0.8 mb/d higher y/y but 0.2 mb/d lower than December 2023 production.

Whereas the short-term oil price outlook appears murky, leading oil agencies remain largely bullish about the long-term outlook. Last week, the International Energy Agency (IEA) published its latest monthly Oil Market Report (OMR), including its first detailed 2025 forecast. The Paris-based energy watchdog predicted that global oil demand in 2025 demand will be 1.147 mb/d higher than 2024 levels, higher than the 1.0 mb/d estimate it had released in June 2023. Other leading agencies have predicted even higher demand growth in 2025: the EIA forecast is 1.351 mb/d, Standard Chartered’s forecast is 1.444 mb/d while the OPEC Secretariat has predicted a 1.847 mb/d increase in demand.

Interestingly, over the medium-and long-term, only the IEA sees global oil demand peaking before 2030, even in its most optimistic forecast (high growth). However, the IEA says an oil demand peak doesn’t necessarily mean a rapid plunge in fossil fuel consumption is imminent, adding that it will probably be followed by “an undulating plateau lasting for many years.”

The EIA is the most bullish on long-term oil demand, and has predicted a demand peak will come in 2050 while the OPEC Secretariat sees it coming five years earlier. Meanwhile, Standard Chartered has predicted global oil demand will hit 110.2 mb/d in 2030 and increase further to 113.5 mb/d in 2035. However, the commodity experts have not projected a demand peak beyond the end of their modeling horizon in 2035. According to StanChart, a structural long-term peak is very unlikely within 10 years despite a high probability of cyclical downturns over the period. StanChart has argued that the current gulf between demand views creates significant investment uncertainty which that’s likely to force longer-term prices higher.

In other words, the energy agencies appear to agree that an oil demand peak is nowhere on the horizon.

Source: Standard Chartered Research

Traders Still Betting On The Energy Sector

The energy sector has been a standout performer in the current year, managing a 15.8% return in the year-to-date, the second highest amongst 11 U.S. market sectors. However, the sector has slipped nearly 5% over the past week with Wall Street experts warning that oil prices sit in a precarious position, which could lead to price swings as geopolitical tensions continue to escalate all throughout the Middle East.

Thankfully, traders are still betting on the energy sector.

Last week, U.S. fund assets (exchange-traded funds and conventional funds) recorded $29.7B in net outflows–in large part to money market funds–marking the third week in four that money flowed from the space. Money market funds recorded $35.3B in net outflows, equity funds lost $1B, commodities funds gave back $207M, and mixed-assets funds observed outflows of $168M.

Interestingly, two funds that recorded the most significant amount of capital inflows on the week were the Invesco S&P 500 Equal Weight ETF (NYSEARCA:RSP) at $2.8B and the Energy Select Sector SPDR Fund (NYSEARCA:XLE) at $756M.

Oil and gas stocks also remain among the least shorted. Last month, average short interest across energy stocks in the S&P 500 index increased 14 basis points to 2.56% of shares floating at the end of the month. APA Corp. (NYSE:APA) was the most-shorted energy stock, with 22.1 million shares sold short as of March 31, or just 5.98% of the shares float. EQT (NYSE:EQT) was the second most shorted energy stock at 5.85% of shares float, while Occidental Petroleum (NYSE:OXY) and Valero (NYSE:VLO) were in third and fourth place with 5.58% and 3.35%, of their floats sold short, respectively.

In comparison, medical services company IMAC Holdings Inc. is the most shorted stock in the S&P 500 with nearly 95% of its float sold short.

(inconvenient left hand anti-CO2 progressivism v. right hand pro-migration progressivism fact)

native birth rates (of all races and ethnicities) has been below 2.1 or declining for decades in the West, since the early 1970’s for Germany.

The West would be at near zero-negative population growth but for immigration.

Just saying, especially as this post is more about the financial side of continued oil demand. Not interested in a pointless discussion about the merits/detriments of (selective) de facto open borders during the Biden administration.

It’s not just the West. Japan, South Korea, Russia, and China are all seeing population declines. And even in India, the past 15 years have seen fewer births than the years before, which means that their population decline is coming. Of the five most populous countries on the planet, only Pakistan is rapidly growing.

The phenomenon seems to be widespread. I’m not sure what’s causing it.

>>> I’m not sure what’s causing it.

consumerist hyper-individualism, affecting men and women—-obviously not in all circumstances. (IMO).

Having a kid(s) is the ultimate in deferred gratification.

US female fertility was <2.1 in the mid-1970's long before immigration became a hot button issue.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/SPDYNTFRTINUSA

Then throw in other relevant reasons like real disposable income for the bottom 50%, etc.

Obviously there cannot be a switch from oil until all the capital invested in building all those oil wells, pipelines and refineries over the past century has been recouped. As soon as that money has been paid back, then they will make the switch.

There hasn’t been much investing in oil lately and you could hear the Russians, the Arabs, etc. complaining about it. The minimum rate of return in the sector is 8%. How long it would take to recoup the investment, at least for the lenders?

two seconds with search

https://search.brave.com/search?q=oil+and+gas+capex&source=desktop

Capex oil and gas was suppressed during Covid (what a shock), but grew last year 11% to 535 billion.

That is a whole lot of capex. It just aint in California.

Integration of infrastructure to complement decline in crude oil production is one of three system views that seems to be delayed.

Engineering has to improve lest no schedule is reliable

Good thing no military anywhere runs on oil.

Population decline or not, the world is using more energy than ever.

And I’d say the population decline is still outstripped by an overall growing global population.

Great Read: Countdown- by Alan Weisman.

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/18453080-countdown

Maybe when we reach peak population we should talk about peak oil…

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Projections_of_population_growth

Blame:

Bullying bankster barons (here’s lookin’ at ya, Jamie) press-ganging knowledge workers back to shiny office towers downtown, when they know damn well the work could be done from home, saving commutes & gas.

Cretinous charlatans promoting excessive travel and stupidities like ‘destination weddings’

Simple math – the amount of stored energy in a unit of gasoline (energy density) still exceeds anything fashionable like EV batteries, except nuclear, which isn’t fashionable.

The argument on the peak oil supply side is not that the spice will stop flowing anytime soon, but that the cost will unavoidably rise due to the greater expense of getting it out of the ground, as all the oil equivalents of low hanging fruit get picked and what’s left takes more effort and more technology. So the demand side will at some point be dragged down by the higher prices. Adding resource wars to the mix will also divert some money away from the demand side. I realize a lot of demand is “ineleastic”, but without money to pay for it, some people will be shut off.

Peak demand? Of course not! A barrel of that black gold does the work of hundreds of humans. Supply, and other little issues like climate change will put a stop to it.

https://www.artberman.com/blog/radical-acceptance-of-the-human-predicament/

Matthew Simmons was talking about supply not demand. There is a world of difference. Apparently peak conventional oil supply peaked in the mid to late 2000s, and peak unconventional oil (fracking) peaked in 2018.

I think Standard Chartered is being intentionally misleading here.

On the supply side commentators like Luke Gromen have analysed this area in terms of ‘peak cheap energy’

Luke Gromen: “Peak Cheap Oil and the Global Reserve Currency”

There is a lot of oil. However, the era of ‘easy access’ to oil is largely over. Extraction from new wells is likely to be more expensive (inflationary).

Yeah, the point with Peak Oil, afaik, is not so much oil will ‘run out’ per se, but that the it’ll become more and more expensive to extract it, thus driving prices up (which perversely could make supply even greater) and staying up. As Germany shows, high energy prices can be quite a problem. Solutions like fracking require financial metaphysics like ZIRP which come with their own, possibly even greater, problems.

Perhaps, but then again, the vast oil deposits in Siberia will become less expensive as the globe warms; it’s just that they won’t make their way to Western markets. And the potential for energy growth in the Chinese market is ginormous (and the Indian market, and lets not forget Africa and indonesia, and….. well, the global majority).

Oh goody. And after that oil is all sold and burned, the follow-on global warming should melt all the ice off of Greenland and Antarctica which will let the seekers of coal, gas and oil find new vast deposits all over Greenland and Antarctica. And sell them all for burning.