Yves here. This article on the effort to move to cleaner energy sources suffers from being written by economists. It sees falling costs of these new power technologies as having the promise of faster uptake. But it also presents offsetting forces, such as “‘distributional effects” (key interests not wanting their rice bowls broken; also lower income households being unable to afford green tech absent big subsidies, which are being cut due to competing demands like more war). Another bugboo is “populism” as in supposedly ideologically-motivated opposition to climate-friendly policies.

That is not to say that there is not substantial “because freedumb” opposition to efforts to reduce greenhouse gases, since they entail a lot of government intervention: subsidies, taxes, prohibitions, regulation. But here and in many cases, resistance to uptake of these newer energy sources is not due simply to libertarian cussedness but often to bona fide issues that transition touts are loath to acknowledge.

Back in the stone ages of my youth, I had a gig where I got to evaluate pretty much all the oddball tech deals that came in over the transom to a well-heeled VC fund. They had bona fide experts on normal tech like computers, software, communications. I got all the “none of the above” deals, like a new way to make synthetic diamonds, thin film solar panels, advanced batteries, a new cooking technology, and even what are now called QR codes (this over a decade before smart phones). They saw someone was going to have to figure them out de novo and I would be as good as anyone else they had to assign to do that.

I quickly worked out that most investors got derailed by letting the inventors pull them into focusing on whether the new technology performed as advertised. That was necessary but far from sufficient to see if an investment made sense.

The critical questions, which I soon inferred many moneybags overlooked, were:

1. What were the competing products and technologies, and how did this offering stack up? The inventors almost without exception defined competition too narrowly, as around their technology, and not in terms of what customers or consumers would see as potential substitutes.

2. How much will consumers/customers need to change behavior to employ this new technology?

3. How long will it take to achieve production efficiencies?

Let’s start with electric vehicles. Sales in the US have stalled. One common belief, with a lot of merit, is prices are still too high for many potential buyers. But there is a tendency to wave off #2 type issues, above all, charging. There aren’t enough EV charging stations relative to what will be, and arguably now is needed, so home charging remains very important. The cost of having an EV run out of charge is higher than having a gas car go empty, since an EV has to be towed. So there’s greater downside and cost. Most importantly, despite the press tending to focus on consumers not yet eating enough of the EV dogfood, there’s a failure to deal with the faltering state of the US grid, the reported failure of utilities to invest to increase capacity, and the resulting potential for brownouts and rolling blackouts. I am sure readers can add other EV questions, like heavier cars leading to shorter tire life, and replacing tires is not just a hard cost but also a time cast.

So this article implicitly ignores some of the neglected real world issues with a big technology/infrastructure changeover as bona fide reasons for foot-dragging.

By Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas, Research Director and Economic Counsellor International Monetary Fund; Director, Clausen Center for International Business and Policy; S.K. and Angela Chan Professor of Global Management in the Department of Economics and Haas School of Business University Of California, Berkeley; Gregor Schwerhoff, Economist International Monetary Fund; and Antonio Spilimbergo, Deputy Director, IMF Research Department International Monetary Fund. .Originally published at VoxEU

The ambition of the Paris Agreement is to limit global warming to “well below 2°C”. This column argues that while some progress towards this aim has been made, substantially more policy action is required. Since 2015, new challenges have emerged for climate policy, including rising populism, shrinking fiscal space, a surge in inflation, higher interest rates, and concerns for energy security. At the same time, technology has progressed faster than expected, bringing a substantial cost reduction for green energy. The success of green policies in containing greenhouse gases depends on the race between political backlash and technological progress.

Recent developments in climate policy paint a gloomy picture: the UK government is backtracking on previous climate commitments; the US is delaying and watering down planned pollution regulation; and China and India continue to build coal power plants. 1 As a result, current efforts are far from sufficient to honour the 2015 Paris Agreement, which requires limiting global warming to “well below 2°C” (Black et al. 2023).

Since then, new political challenges have been added to existing ones (Gourinchas et al. 2024). Among the existing domestic challenges are the distributional effects of climate policy. Even a well-designed climate policy, with minimal impact on aggregate activity (Metcalf and Stock 2023), could lead to significant sectoral reallocation. This causes political resistance from sectors expecting to shrink. The voluntary nature of the Paris Agreement is another existing challenge. It causes concerns about losing competitiveness through climate policy if other countries do not comply.

Among the new challenges are the economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and its aftermath. Government programmes to support households and sectors affected by the pandemic have resulted in much-reduced fiscal space to finance the green transition. At the same time, the surge in inflation forced central banks to raise interest rates. Higher rates curtail financing for clean technology investments more than for conventional technology, because clean technology typically has a more front-loaded investment profile (Hirth and Steckel 2016).

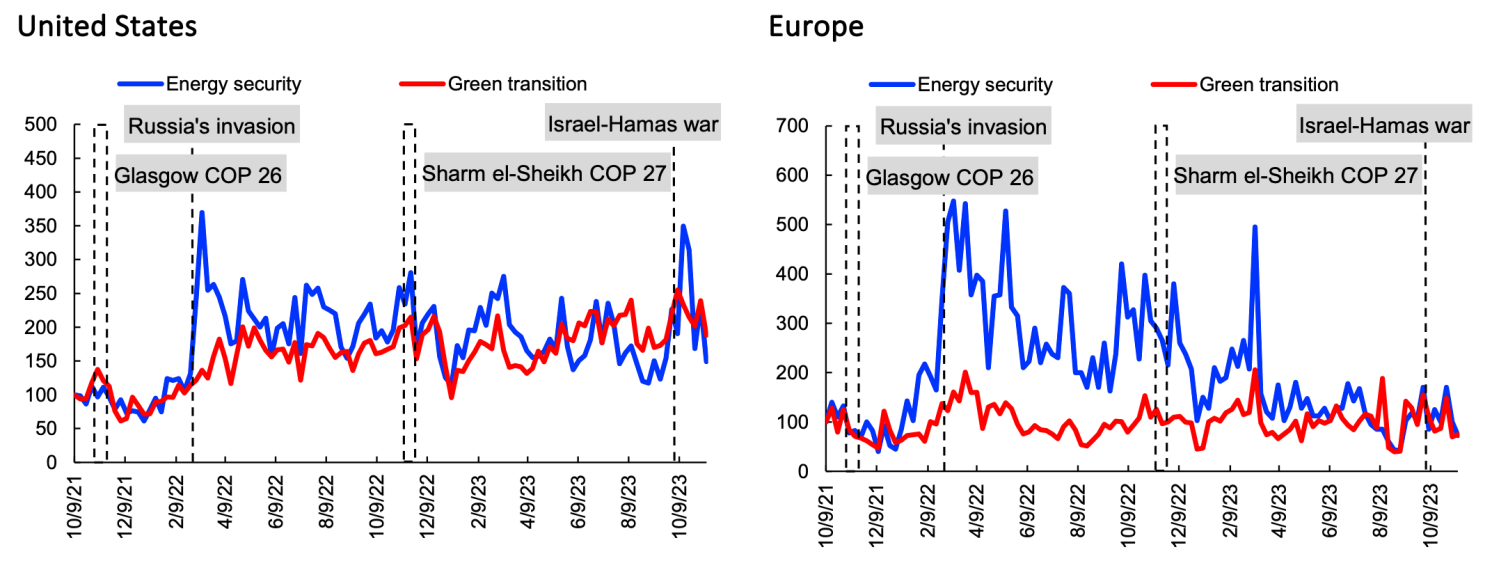

Additional new challenges arise from the effect of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on energy supply. With the abrupt decrease in energy trade from Russia to Europe, concerns about energy security soared and remained high for over a year (Figure 1.) The scramble to secure energy supply resulted in increased investments in fossil fuel infrastructure, especially oil and natural gas (IEA 2023). At the same time, Russia re-directed its supply of oil and natural gas away from Europe to China and India at a discount, which increased the consumption of these fuels in these two countries.

Figure 1 Weekly number of US and European newspaper articles referencing “energy security” and “green transition”, 9 October 2021 to 9 October 2023 (9 October 2021 = 100)

Sources: ProQuest, IMF staff calculations.

Note: The green transition line comprises both “green transition” and “energy transition.”

A third group of challenges arises from rising populism. Populist movements have tended to challenge climate policies following the narrative that climate policy is a project of the ‘elites’, who stand against the will of ‘the people’, similarly to what happened to health policies during COVID-19 (Fiorino 2022, Spilimbergo 2021). Being so visible, carbon pricing – the most efficient economic tool for emission reductions – has become a primary target and source for discontent. For instance, the ‘yellow vest’ protests in France stopped an increase in gasoline taxes in 2018, and the recent protests in Europe in the agriculture and transportation sectors are focused on the Green Deal. As a result of rising populist pressures, governments have leaned against previous climate policy instead of advancing it. In the US, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) achieved support in the US Congress partly through potentially protectionist measures, such as local content requirements that might contravene WTO rules. This reduces the opportunities for trade partners to benefit from the US green investment push. The IRA also generates an estimated $391 billion in expenses (CRFB 2022), while carbon pricing would have generated a revenue.

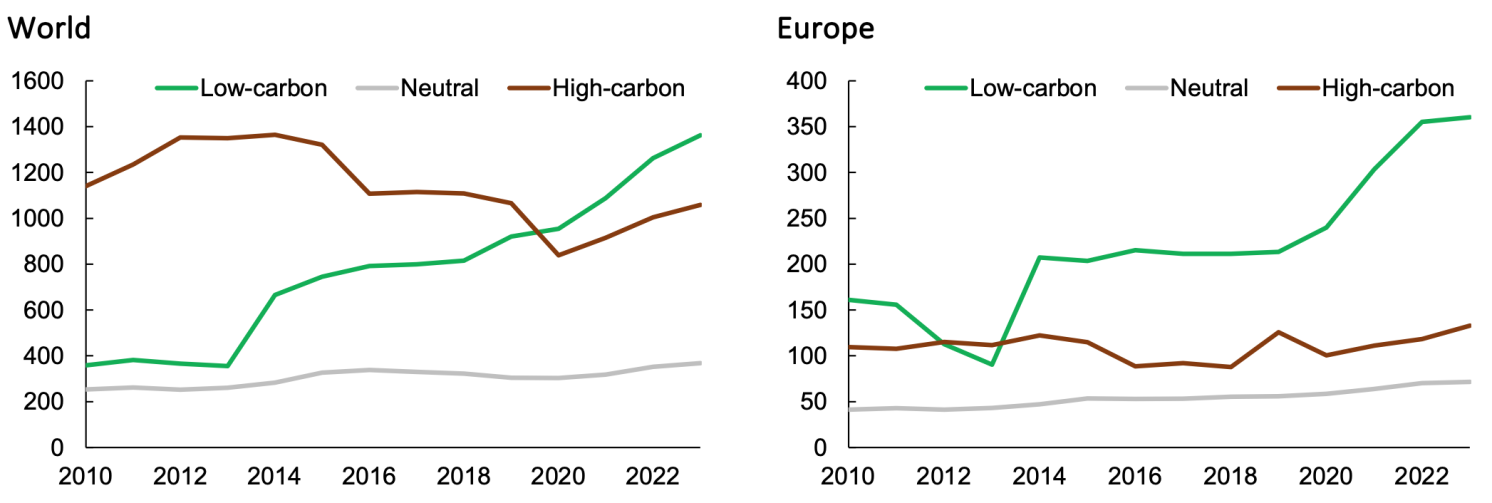

At the same time, climate policy was supported by significantly faster than expected technological achievements. This translated into rapid declines in the prices of low-carbon energy. As a result, the share of investments allocated to low-carbon energy technology has surpassed the share going to high-carbon energy technology (Figure 2). This process is self-reinforcing through two mechanisms. The first is learning by doing. This is most striking for solar panels: it is estimated that each doubling in cumulative production capacity in solar photovoltaics reduces prices by 22.5% (Creutzig et al. 2017). The speed of these developments has surprised even experts. Until recently, World Energy Outlook reports from the International Energy Agency projected solar energy production well below the level of what eventually materialised.

Figure 2 Global energy investment, 2010–23 (billions of 2021 USD)

Sources: IEA (2023b), IMF staff calculations.

Note: Low-carbon = renewables, nuclear, fossil fuels with carbon capture and storage, and energy efficiency; Neutral = electricity networks and storage; High-carbon = fossil fuel generation and fuel production; 2023 numbers are IEA estimates from May 2023.

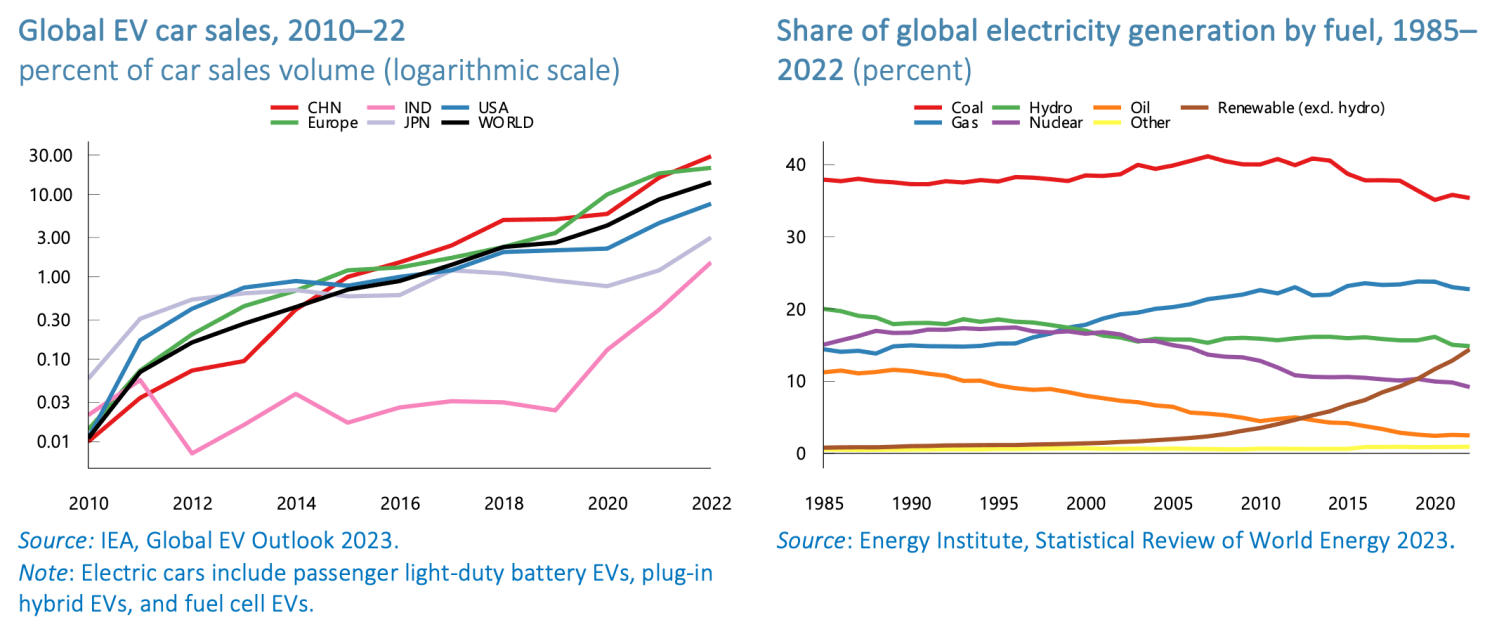

The second self-reinforcing mechanism is network externalities. Until a few years ago, applied research, supply chains and human capital were fully locked into a fossil fuel equilibrium. For example, refuelling a conventional car is extremely convenient due to a dense network of petrol stations. Now, electric vehicles and renewable energy generation have reached considerable market shares and continue to grow strongly globally (Figure 3). As low-carbon infrastructure expands, low-carbon technology becomes locked in. Already, the boom in low-carbon technology is significantly affecting investments in oil and natural gas, and market expectations are changing (Bogmans et al. 2023). Tellingly, even the energy crisis of 2022 did not cause an increase in investments for fossil fuel-based powerplants (IEA 2023). For automobile manufacturers, for example, it is more profitable to invest all research and development funds into one technology in order stay at the technology frontier. Once a critical threshold is reached, a new self-sustaining equilibrium of electric vehicles can emerge (Koch et al. 2022).

Figure 3 Global electric vehicle (EV) sales and electricity generation sources

How should policymakers navigate the race between political backlash and technological progress? First, they should further enable low-carbon technology development. Reinforcing the ongoing shift to clean technology could involve restricting sales of high-pollution goods, taxation, or phasing out polluting technologies (Van Der Ploeg and Venables 2023). The government also has an important role in directing basic research towards technologies – such as green hydrogen and negative emission technology – that are currently still expensive but are needed at a large scale by mid-century. In addition, the diffusion of technology to emerging markets and developing economies needs to be actively supported. Key to this are climate policies, both among innovating countries and recipients of technology transfers, as well as lower trade barriers (Hasna et al. 2023).

Second, climate policies should be designed to ensure fair burden sharing within and across countries, to prevent further political backlash. Surveys show that support for climate policies increases when they are effective, social fairness is ensured, and the policies are communicated well (Dechezleprêtre et al. 2022). Climate policy also needs to be designed in a way that supports international cooperation. On this, the IRA is an interesting example. The protectionist features of the policy package are not cooperative and should not be imitated. At the same time, the package is expected to accelerate low-carbon technology deployment in the US and, as a result, boost clean technology innovation. The net effect on other countries could well be positive. It is hoped that these positive spillovers will be sufficient to avert a harmful round of protectionist retaliation from other countries. But designing climate policies that are fully consistent with the international trading system is possible – and would be even more beneficial.

See original post for references

I think this might have posted early: all lead and no article. :-)

“The government also has an important role in directing basic research towards technologies – such as green hydrogen and negative emission technology…”

Yes and no. Yes to hydrogen, which can burn hot enough to replace fossil fuels, and no to negative emission technologies, which seem like nothing more than greenwashing so that we can use more dirty fuels but not feel so bad about it.

“A third group of challenges arises from rising populism. Populist movements have tended to challenge climate policies following the narrative that climate policy is a project of the ‘elites’, who stand against the will of ‘the people’,”

Well, we the people/plebs are told to cut back on air travel, to drive less, to eat less meat/more bugs, shower for less time, heat our homes less, etc. etc.

And yet, the ‘elites’ continue to use private jets, often to fly between their numerous massive need a lot of heating and A/C homes, enjoy unrestricted diets, drive top of the range cars ad infinitum.

This do as we say, not as we do is a big problem when trying to claim it is not a project of the elites. Their behaviour makes it look very much like it is.

Yes, it’s difficult to hear what they are saying over the dull roar of their own hypocritical actions.

Yes the Al Gore and his mansion problem. The essence seems to be that while virtue signaling is easy and low cost actual virtue doesn’t come naturally. I used to be a fan of Larry David’s Curb Your Enthusiasm and when the show started out he was driving a Prius and by the later seasons he had ditched the small car for a luxury BMW and used ethic humor props in what was once self satire. Edgy had curdled into smarmy.

And so current culture with its celebration of self realization works against the social solidarity needed for larger goals like solving the climate problem. The complacency re Gaza among the upper echelons shows they were never really serious about bigotry either. We have DEI simultaneous with Palestinians as the new blacks.

The fish really does rot from the head metaphorically if not actually. Perhaps a rising generation can do better.

“Perhaps a rising generation can do better.”

I wish, but right now it seems split between doubling down on the existing hustle, or out and out fascism…

words point to hustle, actions point to fascism….

Given that we earlier generations have diminished community and religion, removed the gender handrails, magnified racism and sexism, over-egged the climate pudding and made it impossible to buy a home, I think the rising generation already have more than enough on their plate.

NYC saw this pretty abruptly: PMC/ yuppie’s media conflated EVs with Tesla* (funny, huh?) when, what we’d noticed “during COVID,” were scores-of-thousands of HEAVY, silent, unlit e-bikes running lights in the wrong direction @ 22-38mph (frequently on sidewalks, dodging in & out of staggering survivors). Now, NY1’s going nuts, trying to equate e-mobility scooters, unicycles & bikes with “the help” out to kill affluent white people, burn down the city with slapped together batteries & of course: SPY for Chinese Communism!

*Foreign market Tesla have BYD components, that WORK & don’t burst into flames. Somehow, PHEV & BEVs are reserved for rich suburban honkies (sure can’t charge them, here in the UWS!)

https://www.nerdwallet.com/article/loans/auto-loans/china-electric-cars

https://electrek.co/2024/04/03/byds-affordable-seagull-likely-launch-uks-cheapest-ev/#:

https://infobrics.org/post/40868/

USA (or english?) do seem to have a bad habit of turning the “leading” brand into a synonym for the category…

Nissan’s Leaf came out, well after Renault’s crapification & plug-in Prius (with 80’s style batteries, you could change out for 20% Toyota’s price) were for us lesser folks. GM forgot to mention the batteries replacement price & reviews all seemed to ignore Kia/ Hyundai, as early adopters were most frequently those least likely to run PHEV off PV or use them as generator, power source & storage for off-grid homes? NYC was hilarious: yuppies going directly from gas/diesel guzzling Audi, BMW SUVs to i3 or Tesla, on virtue-signaling impulse, brand-recognition… or wanting to make the WORST people, the richest? To folks, skedaddlng upstate “during COVID” Maybachs were getting dented by all the tools dropping from scaffolding, or some damn self esteem BS fad!

Not only the english, I guarantee it.

Like some incantation? Cheap e-mobility, a return to mass transit, work from home, cycling & fear of flying did LOTS more to demonstrate the kinds of real AGW-mitigation virtue signaling PMC can’t conjur up, squealing Rumpelstiltskin or consuming their way out of what’s BEEN done to victims red-lined into sacrifice zones, so delusional senile yuppies could play Jetsons & make white-flight suburbia GREAT again?

Like Covid, climate change is a real threat. But the regime used Covid as a justification for measures that benefited elites at the expense of ordinary people. As NC has copiously documented, they didn’t even properly protect us from the disease. If anything, the measures they did take were used as excuses for letting the virus run rampant. Why trust that climate change policies will be any different?

People started to talk about the “regime” because this was not a phenomenon of individual countries. Across the West, governments, multinational corporations and NGOs acted in lockstep conformity. Whatever the regime is, people didn’t elect it and don’t trust it.

I watched in real time as people opposed to vaccine mandates applied the same skepticism to climate change policies. People who saw science and doctors censored during Covid logically asked whether the fossil fuel industry’s claims about about climate change censorship and groupthink were also true. Across the political spectrum, the failed and self-serving Covid response undermined faith that any policy of the regime can be taken at face value – especially if it is promoted on moral grounds. People hear the regime talk about climate change, think “you will own nothing and you will be happy,” and respond “hell no.”

Climate change is a potentially catastrophic threat, but can we trust that government will act in the public interest? I no longer think so. I think it is more likely that climate change will be used as an excuse for concentrating wealth and power. Positive environmental impact, if any, will be incidental.

Many people go a step further and figure that climate change is not a threat, just as they believe that Covid is not especially dangerous. I think they are mistaken – but who can blame them? A regime without legitimacy cannot be trusted on anything.

By contrast, here’s a mechanic talking about the economics.

As the owner of a plug-in hybrid (Chevy Volt), we would drive ~50 electric miles for our commute, round-trip.

The Volt replaced a Honda Civic–a nice car, too. When we drove the Civic for commuting, it cost $70/month in gas, plus maintenance.

Our electricity bills increased $4/month when we got the Volt, and the gasoline bill went to zero. So, with home charging, net savings of $66/month.

Internal Combustion Engines have ~2,000 parts. Electric motors have ~7. Guess whose maintenance is more frequent and more expensive?

I know Yves is saying electrifying cars is “dog food,” but that hasn’t been our experience.

Overall, the more genuine solution would be building less sprawl (where every significant trip must be a single-occupant-auto commute) and more transit… But that’s still a pipe dream.

You’re lucky to have a safe place to charge your right-sized EV. If you charge it in Los Angeles your likely using coal generated electricity. Adding a charging station to one’s home is a substantial additional cost to owning and EV. The ChargePoint company that apartment owners relied on is now bankrupt and their services not available in my town.

While ICE vehicles are complex they are amazingly durable and adaptable. Even at $5/gal gas they are more affordable than what Tesla offers.

Fewer cars and more efficient public transit is the radical conservation needed.

“Government programmes to support households and sectors affected by the pandemic have resulted in much-reduced fiscal space to finance the green transition. At the same time, the surge in inflation forced central banks to raise interest rates.”

Nonsense macro like this is unhelpful. “Fiscal space” is a feature of hard currency regimes of the past and no longer applicable to currency issuers. And central banks are never “forced” into their rate decisions by anything other than their own “mind forg’d manacles.”

The most direct route to overcoming the objections of those distributionally harmed by the energy transition is to “stuff their mouths with gold.” Bad macro premises are the biggest obstacle to getting on with it.

“Bad macro premises are the biggest obstacle to getting on with it.”

Nope. Real-world technical constraints are the biggest obstacles, and we ignore them at our peril. It’s certainly possible to spend infinite amounts of money under a fiat money regime, but that doesn’t enable us to purchase infinite amounts of real-world resources.

For example, if we have a “plan” to convert the US to 100% renewable energy by 2035 that requires 500 million workers, that requires 500% of the world’s copper reserves and 2000% of the world’s lithium reserves, and will release 250 billion tons of CO2 during construction and deployment, then it will fail. Fiat vs hard currency doesn’t matter. There simply aren’t enough people and material available for such a plan, nor would we wish to endure the associated environmental damage.

That’s been the problem will all of the plans that our purported leaders have offered. As best I can tell, nobody has put together a firm plan that lists all of the equipment that would have to be deployed and then determined whether or not we can procure the material, labor, energy, and real-estate resources necessary to build and install it. What we instead see is politicians playing “whack-a-mole” with whatever shortage is biting us most acutely at the moment. [Or, more accurately, whatever shortage or fad is getting the most play in the press.]

And in the world of grid energy storage, I can assure you that our leaders have massively underestimated the resources required. Back in 2018, James Hansen said (in an article in the Boston Globe):

In the six years that have passed since Hansen wrote this commentary, I have seen nothing that convinces me he’s wrong. Global CO2 emissions continue to rise year after year. Fiat currencies won’t rescue bad plans.

Amen, brother (or sister) Grumpy.

One quibble: The politics of any transition is made more difficult by those unemployed by the change. Something like a job guarantee would be affordable, resourced, and kinder to those displaced…but I see nothing like this on the table, unless you want to talk military recruitment. That’s the US’ version of a job guarantee.

You spectacularly missed my point. I wasn’t talking about the technical barriers, but rather the political ones masquerading as economics.

Sorry, your obstacle is smaller :)

Do a search on YouTube for Simon Michaux and watch a few of the talks and interviews he has given. He dives deep into the materials that will be required to achieve the “energy transition” and concludes that it’s just not possible without major leaps in technology at the very least.

I have seen other similar analyses, but am yet to see anything that even vaguely attempts to show how it can be achieved, which is telling.

I stopped reading when they are using a study from 2017 about solar panels. 2017 study means 2015 and maybe 2016 year data. That’s ancient history for solar. It was right in the sweet spot of dropping prices. But the last 4-5 years prices have been very flat. Currently there is quite a glut causing some large if temporary(?) price drops.

Wind has also seen a similar trajectory, dropping then stabilizing then increasing. With the increase because of material and labor increases.

Speaking of political implications of the transition, I’ve been wondering what would become of the vast expanses of highly subsidized corn monoculture spread across the American heartland, if the large mandated ethanol demand for use in gasoline blends were to evaporate? Whatever would ADM (and their protégés in government) do?

The misuse of money, the incentive, was what got us here. Let’s use it to get outta here. Why not? Why should we gin up new industries based on the same old concepts of material gain so we can get ahead for the moment and survive? We can simply use money to pay people to live differently. We’ve already deindustrialized and that didn’t work so let’s try definancializing. Create a document, a constitution for the restoration of the planet, which supports everyone with the basics. Food, shelter, medicine, various services, education, etc. Instead of financing an industrial economy to keep the profits coming in, we can just allot everyone the necessary “credit” to thrive. The underlying requirement for this break with industrialism, would be some level of constructive work for everyone – a level that does not harm the planet. Designing a sustainable economy based on industrial production of billions of electric vehicles is an oxymoron. We simply need to eliminate the stuff that is counterproductive for our purposes. So, what are our purposes?

Yves’ summary and commentary on the article was better than the article itself. To quote: “But here and in many cases, resistance to uptake of these newer energy sources is not due simply to libertarian cussedness but often to bona fide issues that transition touts are loath to acknowledge.”

Yep. One of these bona fide issues is the need for curtailment. Last year California curtailed (i.e., threw away) over 2.6 TWh (!!) of potential renewable energy generation because it came at the wrong time of day: https://www.caiso.com/informed/Pages/ManagingOversupply.aspx. And Ireland curtailed over 12% of their potential generation: https://blog.energyelephant.com/wind_curtailment_in_ireland/. Ouch. And these issues are driven purely by the technical requirements of the grid, and it’ll only get worse as more renewable energy assets are deployed.

And I very much liked Yves’ list of “critical questions”, but I do have a suggested change to the second question: “2. How much will consumers/customers/providers need to change behavior to employ this new technology?”

I mention this because electricity providers are having to wildly vary the output levels on their conventional equipment to compensate for the output swings that are intrinsic to renewable energy equipment. The net result is more thermal cycles on the equipment (which reduces service life), and the capital costs of said equipment are spread among fewer MWh. This means more costs elsewhere in the overall system.

The net result is higher electricity prices. California has embraced renewables, but even with the touted “substantial cost reductions,” they have the 3rd most expensive electricity in the nation at $0.295 USD per kWh. [Only Rhode Island and Hawaii are more expensive.] Ireland has embraced renewables even more strongly, and they have the most expensive electricity on the planet (at $0.533 USD per kWh).

Here in the foothills of Appalachia (where they still burn a lot of coal), I pay $0.135 USD per kWh. In nuclear-heavy South Korea, they pay only $0.124 USD per kWh.

problem w/solar is that solar power output peaks at solar noon (which can be as late as 1:45 depending on where you are in your time zone).

Peak AC usage in the summer comes at 3p to 5:30p—the one-two punch of peak temps and people arriving at home, turning on their AC (and perhaps in the future, people charging their cars in the afternoon).

Yes. And in the winter it’s even worse. Peak electricity use during winter is around 7AM, when heat pumps are running hard and people are starting to make coffee, cook breakfast, and/or take showers (which makes the hot water heater run). And the solar arrays don’t provide any meaningful contribution until two or three hours later. The timing is all wrong.

Political backlash has 2 components not adequately addressed: First, the defense by powerful industries of what may become stranded assets. This is both the fossil producers and the owners of those assets, be they NOCs, leassors, shareholders and bondholders. These are all well organized and extremely wealthy interests. Not surprising COP27 was in UAE and thousands came representing vested interests to lobby. The IRA certainly was engineered by lawyers and lobbyists representing vested interests.

Second, for the plebes, does the transition provide tangible benefits? Electrification greatly improved quality of life and made the sunbelt far more habitable. Rural electrification had wide support and was essentially socialism. Transition from wood or coal heating and hot water to oil or gas was a huge benefit. Automobiles enabled instant gratification. As damaging as sprawl and automobiles are, they provided the privacy of single family homes as opposed to crowded tenements.

Does the energy transition provide such step-change quality of life benefits for the 99%? I don’t see it. Look at how financialized rooftop solar has become. Had it been done right, it could’ve greatly reduced consumer costs; instead scammers leased panels leaving many with higher bills and reap renewable production credits. EVs require a hefty cost to install home chargers (eg, 30 amp 220V) and charging is very problematic for apartment and urban dwellers (charger rage and shootings certainly will come). Heat pumps require considerable capital expenditures for homes and apartments heated with gas.

Climate can be a civilization ending event. Unfortunately the elites are only concerned with short-term grifting.

Great points, Upstater. And thanks again for your continued advocacy for pumped-water power storage systems.

I agree with your assertion that migration to products which are better for the Earth is governed by the immediate benefits conferred upon the adopter. People tend to be selfish, short-term thinkers, so every new product has to pass that immediate-benefit threshold.

The boat-anchor effect of the “stranded assets” is monstrous, but big as it is, a properly-designed product can, and certainly will overcome it. Electric cars, wind turbines, solar panels, personal computers and work-from-home are notable examples of product benefits overwhelming entrenched boat-anchors.

The key, as I have said many a time, lies in new product development. The key variables are facilitating or impeding new product development are:

1) How many people are doing it,

2) how skilled are those people, and

3. How well do those people cooperate *

Each of those variables is heavily influenced by will. Drive. Determination, etc.

Same as it ever was.

Have you devised a new product today?

===

* Product development is the ultimate team sport. Long-lasting impact, while having fun in a social setting.

I agree with much of what you’re saying.

The biggest tell that the people pushing for the kinds of radical change mass adoption of renewable energy would create in our society aren’t serious is how they’re also the people who are pushing against permanent WFH. In stupid ways too. Biden could be a hero to the employees in his administration by allowing WFH on everything that didn’t have security requirements. He could roll it out as helping the environment and communities throughout the country. He could also use it to push for grants to various communities like Detroit or Cleveland to revitalize their grids to support WFH. Combine that with socialized broadband access and you’d have the start of something really helping people and addressing climates issues. That would reduce a lot of the driving population.

“Here’s the deal, anyone can work for the federal government now, why just the other day, I hired my friend Cornpop to be the chief executive of NOAA. He’s thrilled that it means he doesn’t have to leave Poughkeepsie. Or Scranton. Whatever. The little crap hole he still lives in. But now everyone else in the same crap hole can work for me too! And so can you! And we’ll save lots of energy!”

Of course, this would decimate urban centers. It would also mean giving aid to deplorables. So we already know this will never happen :/

As far as electric cars go. I am hoping Aptera will start production of their car soon as it would solve many of the current issues with electric cars, as it is designed around efficiency, having the aerodynamic drag (CD 0.13) equivalent to that of the f150’s mirrors alone and about half that of a Tesla model 3. It weighs only around 1800 lbs and with only 3 tires may reduce tire wear costs. Optimally can charge itself with 40 miles/day solar. And with about 13 miles/hr charging on 110, depending how gregarious you are, that could alleviate much of the range anxiety by having the option of paying someone $10 to charge for 2hrs off their 110 for a 50 cents of their electricity to get you another 25miles down the road. Not ideal, but much better than calling a tow truck. Major drawback is it is only a two seater, though it has lots (32 cu ft) of cargo space. Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aptera_(solar_electric_vehicle))

New product development, take a (nother) bow.

And the Aptera development was crowd-funded.

Thanks, Henry D. Made my day.

Here is the VW XL1.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Volkswagen_1-litre_car

This time of year (spring in the northern hem., no-very limited AC use), peak electricity usage is roughly 25% higher than the nadir during the graveyard hours (usually around 3-4AM).

Where is the green baseload going to come from? Western-style civilization uses a huge level of inelastic electricity 24/7/365—refrigeration, sewer-water, servers, logistics, hospitals, HVAC, etc.

(happy for a Star Trek-like battery breakthrough, not holding my breath)

A challenge for the green movement which remains largely unaddressed is the developing world and how to bring more than half the worlds population into the fold. Many countries in the developing world contain a significant portion of the worlds carbon sink and storage capacity (e.g. rainforests in South America and Africa) that remain to this day, only marginally compensated for this precious resource for humanity, not to mention the biodiversity they contain). How does the modern world bring this massive segment of humanity along in a fair and just manner?

The Guana PM just pointed this out to a clueless BBC reporter trying to give him shite about the oil fields they are about to develop. “How much have you paid us for the largest preserved forest in South America”.. Orr something like that. It was impressive to see.

It was quite a smack down.

I think it’s very telling that a small country like that is pushing back.

Yes, the people who got rich and fat burning fossil fuels can hardly say “for me, but not for thee” to those who would like to be equally rich and fat.

From an account of a lecture given by Jane Goodall the week of her 90th birthday, linked to here at NC earlier:

https://grist.org/looking-forward/jane-goodalls-legacy-of-empathy-curiosity-and-courage/

I agree that it’s a long and dark tunnel, and it may also be smaller than the crowd that would like to go through it – that is to say, a bottleneck, as environmental sociologist/human ecologist William Catton titled his last book.

When I read analyses like this about the energy transition, I am reminded of the number crunchers at the Department of Defense while McNamara was running the Vietnam War. I might be very, very wrong, of course.

I wonder if fossil-fuel depletion might help explain the dark tunnel metaphor. We have no real alternatives to f-f, and they support this age of plenty pretty much entirely. Gail Tverberg writes on this topic @ Our Finite World.

I can’t figure it out but in my state we have a plan, a road map or whatever to be net-zero by 2050. The independent system operator (ISO-NE) seems to go along with it. The politicians say it will be nirvana. Jobs galore, reduced pollution and we save the world. But I see little actual progress, other than subsidized rooftop and community solar. There is nobody who wants wind turbines anywhere near where they live, and nobody wants to sacrifice farms, forests or nature preserves for solar farms.

Interesting piece. However the most important thing that we can all do to slow the effects of climate change is to only give birth to / father one child over the course of a lifetime. That and shift to a vegetarian diet. The amount of energy / resources that one human being uses over the course of a life time is huge. I just don’t see how we can provide food, water, consumer products, and energy for 9, or 10 or 11 Billion people.

Forcing everyone to purchase an EV is smacks of a heavy hand. Where is all the electricity going to come from? (Perhaps Elon Musk will write an app that will create electricity out of thin air).

Also, the groups that are leading the charge to electrification, the Political Class, the Professional Managerial Class and the Investor Class are the folks that have created and “managed” the great failures of,our time… Vietnam, Globalization, Monetization, Off-Shoring, Out-Sourcing, Afghan war, Iraq War, 2008 Financial Crisis… do you really have faith that they can manage the globe through this transition? Such a scary thought.

However, this energy transition will make a number of the above classes very wealthy and the rest of us… well you know the story already. Interestingly, having people work from home is a great way to reduce fossil fuel usage, and the PMC and Investor Class want us to all get back in our autos and commute to work every day and use fossil fuel while doing so.

I could go on but you get the idea. On another note, I think that NC is a great Blog, I always learn from the articles and also learn much from the comments.