Yves here. It’s revealing that Serious Economist Jeffrey Frankel limits himself to third-world examples in his case studies below on post-election devaluations. Perhaps it would be unseemly to look at, say, the US, UK, Japan, South Korea, or even Australia (admittedly the latter and Canada have their currency values substantially affected by commodity prices). Of course, Frankel might contend that any politically-related currency action in an advanced economy would not amount to a depreciation-level decline. After all, they have independent central banks.

As many, including your humble blogger, have noted, the US is running a very hot fiscal policy along side tight monetary policy. Hence America has persisted in having solid to very strong groaf figures, leading the Fed to persist in tight monetary policy. All of that has led the dollar to trade at very lofty levels.

One has to think the dollar will start to reverse near the election, say in October. But inflation has been very sticky, and it’s interest rates that are buoying the greenback, so it might stay comparatively strong even past the election. In addition, the US has, at least since the Clinton Administration, has had an explicit strong dollar policy. Weak currencies and financial centers do not co-exist happily. The Fed has historically not cared a whit about what moves in interest rates have done in terms of in and out flows to emerging economies, who are routinely whipsawed by hot money moves. One wonders if we will eventually see the Fed become more attentive to the value of the dollar.

Any readers who are currency-knowledgeable are encouraged to opine on which countries might look more attractive as King Dollar retreats from its current high.

By Jeffrey Frankel, Economist and Professor, Harvard Kennedy School. Originally published at VoxEU

An unprecedented number of voters will go to the polls globally in 2024. It has long been noted that incumbents tend to engage in expansive fiscal (and where possible monetary) policy in the run up to elections in order to buoy the economy and therefore their electoral prospects. This column extends this concept to look at exchange rates and finds that currencies frequently depreciate following an election as the incumbent’s efforts to overvalue the currency in the run up to the election are unwound and the new government comes to terms with depleted reserves and current account woes.

Lots of countries are voting, with 2024 an unprecedented year in terms of the number of people who will go to the polls. Recent elections in a number of emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs) have demonstrated anew the proposition that major currency devaluations are more likely to come immediately after an election, rather than before one. Indeed, Nigeria, Turkey, Argentina, Egypt, and Indonesia are five countries that have experienced post-election devaluations within the last year.

The Election–Devaluation Cycle

Economists will recall a 50-year-old paper by Nobel Prize winning professor Bill Nordhaus as essentially initiating research on the political business cycle (PBC). The PBC refers to governments’ general inclination towards fiscal and monetary expansion in the year leading up to an election, in hopes of the incumbent president, or at least the incumbent party, being re-elected. The idea is that growth in output and employment will accelerate before the election, boosting the government’s popularity, whereas the major costs in terms of debt troubles and inflation will come after the election.

But the seminal 1975 paper by Nordhaus also included the prediction of a foreign exchange cycle particularly relevant for EMDEs. That is the proposition that countries generally seek to prop up the value of their currencies before an election, spending down their foreign exchange reserves, if necessary, only to undergo a devaluation after the election.

Nordhaus wrote: “It is predicted that the concern with loss of reserves and balance of payments deficits will be greater in the beginning of electoral regimes, and less toward the end.…The basic difficulty in making intertemporal choices in democratic systems is that the implicit weighting function on consumption has positive weight during the electoral period and zero (or small) weights in the future.”

The devaluation may be undertaken deliberately by an incoming government, choosing to get the unpleasant step – with its unpopular exacerbation of inflation – out of the way while it can still blame it on its predecessors. Or the devaluation may take the form of an overwhelming balance-of-payments crisis soon after the election. Either way, a government has an incentive to hoard international reserves during the early part of its term in office, and to spend them more freely to defend the currency toward the end of its term.

A political leader is almost twice as likely to lose office in the six months following a major devaluation as otherwise, especially among presidential democracies (Frankel 2005). Why are devaluations so unpopular that governments fear to undertake them before elections? In the traditional textbook model, a devaluation stimulates the economy by improving the trade balance. But devaluations are always inflationary in countries which import at least a portion of the basket of goods consumed. Furthermore, devaluations in EMDEs often are contractionary for economic activity, particularly via the adverse balance sheet effects on those domestic borrowers who had incurred debts denominated in dollars.

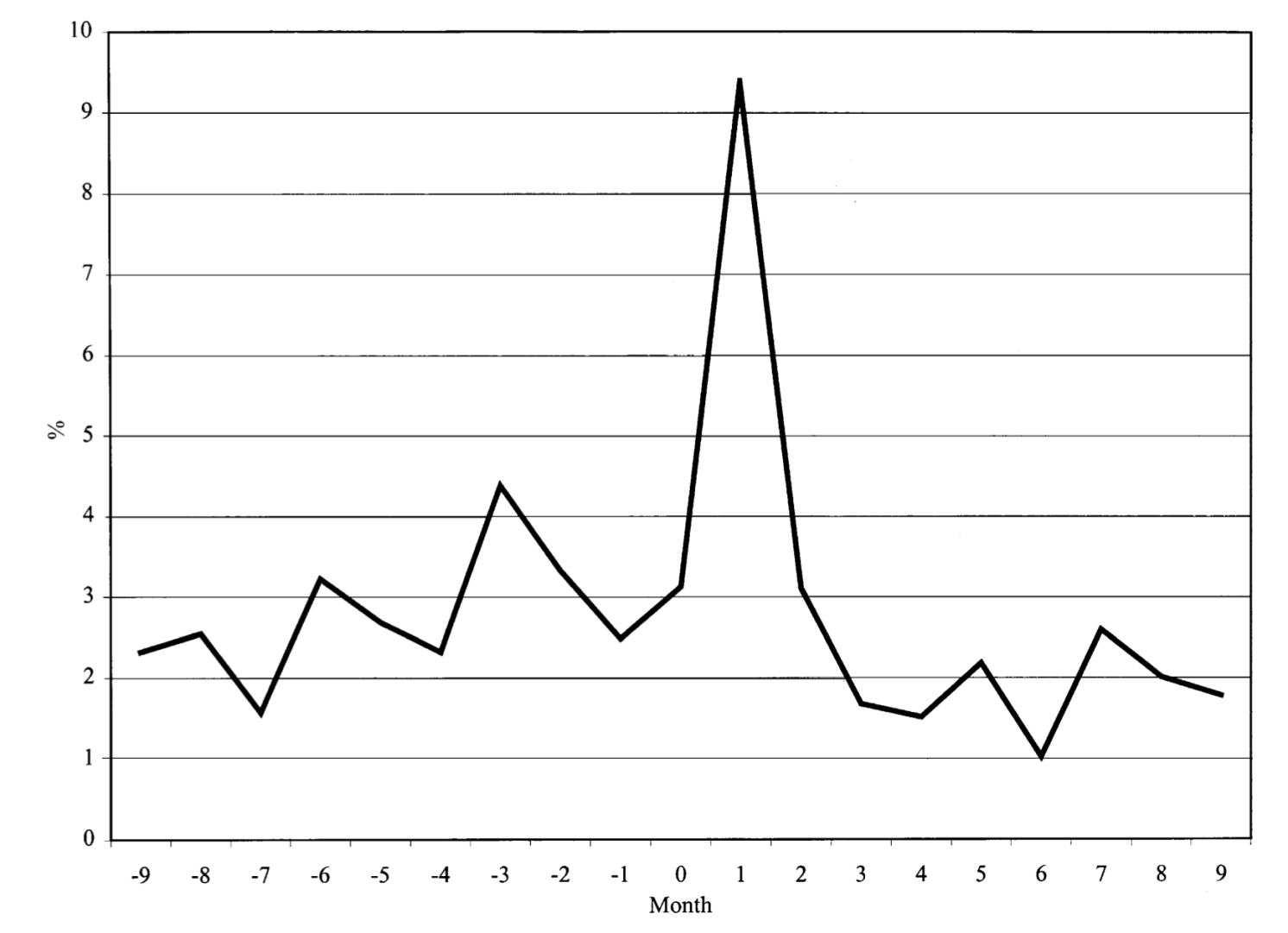

The theory of the political devaluation cycle was developed in a series of papers by Ernesto Stein and co-authors. One might think that voters would wise up to these cycles and vote against a leader who sneakily postponed a needed exchange rate adjustment. But given a lack of information about the true nature of the politicians, voters may in fact be acting rationally. Figure 1, from Stein and Streb (2005) shows that devaluations are far more common in the immediate aftermath of changes in government. (The sample covers 118 episodes of changes, excluding coups, among 26 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean between 1960 and 1994.) 1

Figure 1 Average devaluation pattern before and after elections

Source: Stein and Streb (2004).

Some Devaluations Over the Past Year

Many EMDEs have been under balance-of-payments pressure during the last two years. One factor is that the US Federal Reserve raised interest rates sharply in 2022-23 and is now leaving them higher for longer than markets had been expecting. Consequently, international investors find US treasury bills more attractive than EMDE loans and securities.

A good example of the political devaluation cycle is Nigeria. Africa’s most populous country held a contentious presidential election on 25 February 2023. The incumbent, who was term-limited, had long used foreign exchange intervention, capital controls, and multiple exchange rates to avoid devaluing the currency, the naira. The new Nigerian president, Bola Tinabu, was inaugurated on 29 May 2023. Two weeks later, on 14 June, the government devalued the naira by 49% (from 465 naira/$, to 760 naira/$, computed logarithmically). It soon turned out that this was not enough to restore equilibrium in the balance of payments. At the end of January 2024, the government abandoned its effort to prop up the official value of the naira, devaluing another 45% (from 900 naira/$ to 1,418 naira/$, logarithmically).

A second example is Turkey’s election in May 2023. President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan had long pursued economic growth by obliging the central bank to keep interest rates low – a populist monetary policy that was widely ridiculed because of the president’s insistence that it would reduce soaring inflation – while simultaneously intervening to support the value of the lira. The government guaranteed Turkish bank deposits against depreciation, an expensive and unsustainable way to prolong the currency overvaluation. After the elections, the lira was immediately devalued, as the theory predicts. The currency continued to depreciate during the remainder of the year.

Next, on 19 November 2023, Argentina elected a surprise candidate as president, Javier Milei. Often described as a far-right libertarian, he comes from none of the established political parties. He campaigned on a platform of diminishing sharply the role of the government in the economy and abolishing the ability of the central bank to print money. Milei was sworn in on December 10. Two days later, on 12 December he cut the official value of the peso by more than half (a 78% devaluation, computed logarithmically, from 367 pesos/$ to 800 pesos/$). At the same time, he took a chain saw to government spending such as energy subsidies rapidly achieved a budget surplus, and initiated sweeping reforms. Argentine inflation remains very high, but the central bank stopped losing foreign exchange reserves after the devaluation, again as predicted by the theory.

A fourth example is Egypt, where President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi just started a third term, on 2 April 2024. The economy has been in crisis for some time. Nevertheless, the government had ensured its overwhelming re-election on 10-12 December 2023 by postponing unpleasant economic measures, not to mention by preventing serious opponents from running. The widely expected devaluation of the Egyptian pound, came on 6 March 2024 depreciating 45% (from 31 egyptian pounds/$ to 49 pounds/$, logarithmically). It was part of an enhanced-access IMF programme, which also included the usual unpopular monetary and fiscal discipline.

Finally, in Indonesia the widely liked but term-limited President Jokowi is soon to be succeeded by the Defense Minister Prabowo Subianto, who is less widely liked but was backed by the incumbent in the 14 February election. The rupiah has been depreciating ever since the 20 March announcement of the outcome of the contentious presidential vote. It fell almost to an all-time record low against the dollar on 16 April.

What next?

Of course, the association between elections and the exchange rate is not inevitable. India is undergoing elections now and Mexico will in June. But neither seems especially in need of major currency adjustment.

Venezuela is scheduled to hold a presidential election in July. As with some other countries, the election is expected to be a sham because no major opposition candidates are allowed to run. The economy is in a shambles due to long-time mismanagement featuring hyperinflation in the recent past and a chronically overvalued bolivar. But the same government that essentially outlaws political opposition also essentially outlaws buying foreign exchange. So, equilibrium may not be restored to the foreign exchange market for some time.

To stave off devaluation, these countries do more than just spend their foreign exchange reserves. They often use capital controls or multiple exchange rates, as opposed to allowing free financial markets. That doesn’t invalidate the phenomenon of post-election devaluations; it just works to insulate the governments a bit longer from the need to adjust to the reality of macroeconomic fundamentals. Unfortunately, many of these countries also fail to allow free and fair elections, which works to also insulate the government from the need to respond to the voters’ verdict.

Author’s note: A shorter version of this column appeared on Project Syndicate. I thank Sohaib Nasim for research assistance.

See original post for references

So the value of the US$ will collapse in December? And is this going to happen regardless of who wins in November? Or is Frankel just a bloviating jackass?

It’s already collapsed quite a bit. The strength of the USD is measured against other currencies, if it was measured by the amount of commodities it could buy that would probably be more accurate.

$2400+ gold by the end of the year is likely.

Sorry that is not a valid measure. The dollar is super strong v. pretty much all currencies. You can’t buy coffee with gold anywhere in the world. And in economies that have gone into crisis (Vietnam during its war, Argentina at various points) the value of gold in buying real things like food was WAY below its theoretical value based on investment market prices.

I am not a currency expert, but this statement here “The rupiah has been depreciating ever since the 20 March announcement of the outcome of the contentious presidential vote. ” needs to be put into context. The following, https://tradingeconomics.com/indonesia/currency, shows that devaluation of the Indonesian Rupiah is more the rule than the exception, it’s predictability is almost like the sun rising in the morning every day :(.

Since Jokowi was first elected in 2014, the Rupiah has depreciated by 50% and yet it never affected his popularity. Additionally, in a recent statement, the current President elect, Prabowo also attributed his victory in the recent election to the Jokowi effect, Link in Indonesian. I’ve said in previous comments that the Wizard of Kalorama can learn a thing or two from Jokowi.

The fate of Indonesia really rests on capable bureaucrats like the Indonesian Minister of Finance, Sri Mulyani, who I think will be retained by Prabowo, although at the same time, I think it’s early to tell whether my prediction will come true.

Last but not least, from the following sentence towards the end of the article, “Unfortunately, many of these countries also fail to allow free and fair elections,”, I think the author is simply echoing the the sour grapes sentiment of the US establishment that their preferred candidates didn’t win the elections.

Brad Setzer recently commented that Asian currency devaluations against the dollar tend not to be reversed. Since most are exporting countries, there are powerful interest groups who are generally quite happy to keep things the way they are (since the rich usually have plenty of dollars and Swiss francs, they are rarely directly affected).

In my experience, people only tend to ‘feel’ devaluations if they are travelling abroad. People don’t always connect the rise in price of fuel or food they are complaining about to the devaluation that occurred 6 months before. So it may well be true that in a country like Indonesia, allowing devaluations can be a fairly safe way for a politician to ‘relatively’ painlessly redistribute money from ordinary people to vested interests (usually wealthy business owners). I’m not suggesting this was Jokowi’s plan, but it often works out this way. This is one reason why institutionally weak countries usually end up with banknotes with lots of zeroes on them.

First of all, Jokowi is just one person, so expecting him to fully turn Indonesia into some kind of well oiled machine in 10 years time is frankly too much, especially given his humble beginnings.

Indonesia’s problem is actually pretty simple, after the 2008 crisis, the country ran a trade deficit for many years, which can be seen in this graph https://tradingeconomics.com/indonesia/balance-of-trade.

It would have been worse if Jokowi hadn’t introduced a number of policies mandating foreign companies to manufacture their products in Indonesia if they want to sell to domestic customers. For a short while, that policy actually caused imports to increase, because Indonesia wasn’t producing many of the components required for the final products, but things started to turn sometime in 2020.

I can’t find any links right now, but I’ve a vague memory of reading some studies back when the Euro was being created on whether individual European currencies were politically influenced. From what I remember, there wasn’t a particularly strong link between elections and currency fluctuations. While I’m sure politicians back then were keen on manipulating the domestic currency for their own ends, the need for the institutional apparatus (i.e., finance ministries, central bank, etc) to appear apolitical would have made it very difficult for politicians to force through major monetary changes against official advice. Governments are far more likely to use fiscal measures (i.e. generous budgets before an election, retrenchments immediately after an election), which of course could have knock on monetary impacts, although not always the anticipated one.

Most industrial countries, especially those with strong export industries and big dollar holdings, are quite happy to see the dollar stay very strong – this includes of course China, Japan, Taiwan, ROK and (to a lesser extent), the eurozone, so its hard to see anyone welcoming a major inflow of buyers. If rumours are correct, certainly both the Japanese and Chinese central banks are ruminating on the potential benefits of devaluations (the yen of course has already somewhat succeeded). And of course, even a rumour of devaluation can make a currency far less attractive.

So its hard to see there as being any particularly attractive major safe haven for someone exiting the dollar except possibly the Euro or Sterling, and both currencies have their own particular issues of course, so its hard to see them getting too strong relative to the euro or other major currencies.

I’m no expert in currency movements, but I find it hard to see what would drive the dollar down significantly, as nobody has much incentive to allow their currency to rise too swiftly. If anything, since the US is the buyer of last resort for the rest of the planet, anything that hits its economy can, if anything, make its currency even more attractive as a safe haven. I think only a very dramatic reduction in interest rates could change this, and that assumes everyone else doesn’t follow suit.

In Argentina, Milei is a tool of the rich who won office posing as a populist and then revealed his true colors moments after winning by immediately appointing high officials of the discredited Macri regime to top posts. Seen in the context of his other actions (including the invitation to the US military), his devaluation can be seen as a sop to the country’s powerful ag industry, who likes it for the more favorable pricing it gives to their exports. Meanwhile, as mentioned, inflation continues to rage against the populace, which is now seeing over 50% poverty despite an unemployment rate under 6%—and far from throwing them a lifeline, Milei is ruthlessly stripping away the country’s social welfare programs and boating opely that he intends to repair the economy by causing further suffering. It is not good.

Not good for Venezuela but: Milei is a loyal vassal of el imperio norteamericano: he follows the Washington Consensus to the letter, loves Israel, and US military bases. Our friends in Langley must be very pleased.

Since exchange rate fluctuations gore different oxen, presumably any planned change for electoral gain would require the government in question to have some fairly reliable understanding of which group (the winners or losers from said change) is more numerous or can be relied upon to vote in larger numbers.

There is also the possibility, of course, that such manipulations could take place at the behest of the donor class, electoral outcomes be damned …

If your a country that has to pay debt back to the USA in US dollars – well then higher dollar value means your cash is worth less and you have got to shove any commodities/minerals/ onto a market where everybody else is tossing their stuff – and thus fire sale prices- to raise enough to pay back the vultures – add some interest into the equation and you got your (colonies) in the old debt peonage trap – the new state slaves to US imperialism

Strip and burn the planet

Another thing that might cause the dollar to lose value is if the Europeans were to go ahead and seize all of Russia’s reserves. The loss of confidence in the dollar might not happen overnight, but I think it will cause bilateral transactions to increase in number and value.

I also think this time around the dollar will lose value against gold. The Central Bank of Singapore was never a big buyer of gold, but then something spooked them, and in 2023 they started buying gold in huge quantities. Singapore might not be a hub of innovation that its founders envisioned it to be, but when it comes to finance and money, Singaporean bureaucrats are pretty astute, well they should be since it’s a hub of money laundering for South East Asia and possibly more than that.

The author omitted the very important context and fact that Venezuela is under economic siege warfare. The US has been trying to regime change the country since Chavez. We can recall the theft of Venezuela’s gold by the BoE.

The elections in the US are a total sham, but no mention of that. The implicit assumption is that the US is a shining beacon of democracy and meaningful choice.

The author is clearly blinkered and biased in this regard and damages his own credibility. No matter what one feels about the Venezuelan govt., one must at least make an effort to put national bias aside and analyze the situation as objectively as possible.

“strong groaf figures” I like that. Yves, have you been in east London lately?

But seriously, what kind of economic growth are we talking about? I wonder how much of that “growth” can be attributed to price-gouging, interest, fees and financialized market-rigged “growth” (rather than productive economic activity), inflated medical costs (extortion). etc.? And then the question is: where are all the profits from “growth” going? Into the general economy, or into the hands of the .01% oligarchy?

Also, much of the massive deficit spending, as Michael Hudson often points out, is military in nature and ends up in foreign central banks. The dollar glut gets recycled into USD denominated assets: treasuries, US stocks, bonds, real-estate etc. In this way, the massive deficit spending does not cause domestic inflation, but rather contributes to asset price inflation.

After a decade-plus of mostly lurking here at NC, and recently rather avidly following Profs M. Hudson, S. Kelton and S. Keen, I still consider myself an economics amateur- my motivation has simply been to “follow the money” and “cui bono?”. That said, imho the Fed can pump up the economy by not cutting interest rates until after Nov. elections, and even ‘signal’ the intent to resume the ‘inflation fight’ by a token bump (say 25bp). The commercial (especially) RE market and us ‘deplorables’ will ‘take the pain’ but the private equity and hedgie fat cats will push the market higher and proclaim “life is good!”. After the election (assuming it even takes place ;^\ ) they can start cutting rates which will lower mortgages and RE valuations (sorry speculators!) and Mr. Market will have a “sad”. Business as usual – one hopes…… but If the new multipolar world starts dumping Treasuries then my “pitchfork futures” ought to do nicely. YMMV, of course.

“they can start cutting rates which will lower mortgages and RE valuations (sorry speculators!) and Mr. Market will have a “sad”. Business as usual .”

I think, that by lowering mortgages(interest rates and current interest payments) you will increase RE valuations because it gives the banks more room to lend to the ones willing to go into debt more. The speculator only cares about the largest return – lower rates enable larger returns.

What goes up must come down but, in my experience, the coming down is much slower than the going up. at least- that is (my interpretation) what has been the intent and the result of the bailouts and the pro-speculator ie -(wall street) -sort of a full-on predatory, speculative income and asset baseline support system — the productive economy be damned

In general, lowering interest rates will indeed cause the value of various assets to increase, but it also depends on where you are on the cycle. Cutting interest rates is after all a sign of weakness, not strength. If you look at the following, https://www.statista.com/statistics/188993/annual-change-in-house-prices-in-the-us-since-2008/, you’ll notice that housing prices continued to drop even after the Fed had lowered interest rates to almost zero close to the end of 2009. If consumers continue to bleed and the economy hasn’t bottomed, there’s zero incentive for banks to lend, after all they too probably have plenty of bad assets in their books.

Next time around though, everyone is going to get bailed out and that will probably do “wonders” to the value of the dollar.