By Erik Bleich, Charles A. Dana Professor of Political Science, Middlebury and Christopher Star, Professor of Classics, Middlebury .Originally published at The Conversation

The exponential growth of artificial intelligence over the past year has sparked discussions about whether the era of human domination of our planet is drawing to a close. The most dire predictions claim that the machines will take over within five to 10 years.

Fears of AI are not the only things driving public concern about the end of the world. Climate change and pandemic diseases are also well-known threats. Reporting on these challenges and dubbing them a potential “apocalypse” has become common in the media – so common, in fact, that it might go unnoticed, or may simply be written off as hyperbole.

Is the use of the word “apocalypse” in the media significant? Our common interest in how the American public understands apocalyptic threats brought us together to answer this question. One of us is a scholar of the apocalypse in the ancient world, and the other studies press coverage of contemporary concerns.

By tracing what events the media describe as “apocalyptic,” we can gain insight into our changing fears about potential catastrophes. We have found that discussions of the apocalypse unite the ancient and modern, the religious and secular, and the revelatory and the rational. They show how a term with roots in classical Greece and early Christianity helps us articulate our deepest anxieties today.

What Is an Apocalypse?

Humans have been fascinated by the demise of the world since ancient times. However, the word apocalypse was not intended to convey this preoccupation. In Greek, the verb “apokalyptein” originally meant simply to uncover, or to reveal.

In his dialogue “Protagoras,” Plato used this term to describe how a doctor may ask a patient to uncover his body for a medical exam. He also used it metaphorically when he asked an interlocutor to reveal his thoughts.

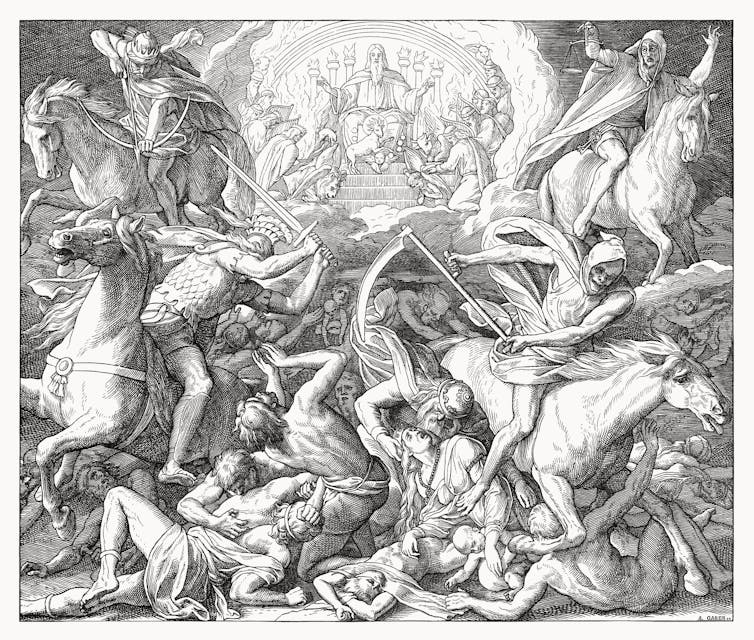

A wood engraving by German painter Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld illustrates a scene from the Book of Revelation.

New Testament authors used the noun “apokalypsis” to refer to the “revelation” of God’s divine plan for the world. In the original Koine Greek version, “apokalypsis” is the first word of the Book of Revelation, which describes not only the impending arrival of a painful inferno for sinners, but also a second coming of Christ that will bring eternal salvation for the faithful.

The Apocalypse in the Contemporary World

Many merican Christians today feel that the day of God’s judgment is just around the corner. In a December 2022 Pew Research Center Survey, 39% of those polled believed they were “living in the end times,” while 10% said that Jesus will “definitely” or “probably” return in their lifetime.

Yet for some believers, the Christian apocalypse is not viewed entirely negatively. Rather, it is a moment that will elevate the righteous and cleanse the world of sinners.

Secular understandings of the word, by contrast, rarely include this redeeming element. An apocalypse is more commonly understood as a cataclysmic, catastrophic event that will irreparably alter our world for the worse. It is something to avoid, not something to await.

What We Fear Most, Decade by Decade

Political communications scholars Christopher Wlezien and Stuart Soroka demonstrate in their research that the media are likely to reflect public opinion even more than they direct it or alter it. While their study focused largely on Americans’ views of important policy decisions, their findings, they argue, apply beyond those domains.

If they are correct, we can use discussions of the apocalypse in the media over the past few decades as a barometer of prevailing public concerns.

Following this logic, we collected all articles mentioning the words “apocalypse” or “apocalyptic” from The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal and The Washington Post between Jan. 1, 1980, and Dec. 31, 2023. After filtering out articles centered on religion and entertainment, there were 9,380 articles that mentioned one or more of four prominent apocalyptic concerns: nuclear war, disease, climate change and AI.

Through the end of the Cold War, fears of nuclear apocalypse predominated not only in the newspaper data we assembled, but also in visual media such as the 1983 post-apocalyptic film “The Day After,” which was watched by as many as 100 million Americans.

By the 1990s, however, articles linking the word apocalypse to climate and disease – in roughly equal measure – had surpassed those focused on nuclear war. By the 2000s, and even more so during the 2010s, newspaper attention had turned squarely in the direction of environmental concerns.

The 2020s disrupted this pattern. COVID-19 caused a spike in articles mentioning the pandemic. There were almost three times as many stories linking disease to the apocalypse in the first four years of this decade compared to the entire 2010s.

In addition, while AI was practically absent from media coverage through 2015, recent technological breakthroughs generated more apocalypse articles touching on AI than on nuclear concerns in 2023 for the first time ever.

What Should We Fear Most?

Do the apocalyptic fears we read about most actually pose the greatest danger to humanity? Some journalists have recently issued warnings that a nuclear war is more plausible than we realize.

That jibes with the perspective of scientists responsible for the Doomsday Clock who track what they think of as the critical threats to human existence. They focus principally on nuclear concerns, followed by climate, biological threats and AI.

It might appear that the use of apocalyptic language to describe these challenges represents an increasing secularization of the concept. For example, the philosopher Giorgio Agamben has argued that the media’s portrayal of COVID-19 as a potentially apocalyptic event reflects the replacement of religion by science. Similarly, the cultural historian Eva Horn has asserted that the contemporary vision of the end of the world is an apocalypse without God.

However, as the Pew poll demonstrates, apocalyptic thinking remains common among American Christians.

The key point is that both religious and secular views of the end of the world make use of the same word. The meaning of “apocalypse” has thus expanded in recent decades from an exclusively religious idea to include other, more human-driven apocalyptic scenarios, such as a “nuclear apocalypse,” a “climate apocalypse,” a “COVID-19 apocalypse” or an “AI apocalypse.”

In short, the reporting of apocalypses in the media does indeed provide a revelation – not of how the world will end but of the ever-increasing ways in which it could end. It also reveals a paradox: that people today often envision the future most vividly when they revive and adapt an ancient word.![]()

AI is not an existential, apocalyptic threat. The human beings who think it’s a good idea to shove it down our throats, maybe, but not the AI itself, which can presumably be unplugged. Plus, judging by recent interactions with it, it’s dumber than a bag of hammers.

Another apocalypse, one I much prefer to the options listed above, four Scandinavians doing heavy metal cello covers of classical music – Hall of the Mountain King

Rock on until it’s all gone!

The current AI is not an existential threat. The near future AI probably will be. The current models may be able to be shutoff, future models probably won’t be.

It doesn’t require animus on the part of the AI; just a goal and sufficient agency.

I’d recommend familiarising yourself with the ideas of Eliezer Yudkowsky (eg https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gA1sNLL6yg4)

Yes I’m familiar with his basilisk thought experiment. I don’t really take it seriously. Again, human beings program these AIs, human beings create the algorithms they run on. If they act badly, it’s because some human being wanted it that way.

You are unfamiliar with the concept of software bug?

The moderation team let a doofus peddling Yudkowsky to post a comment? This techno cult of neurodivergent losers needs to die already. Go back to LessWrong, please.

Please read our Moderation policies. Posting material from provocative sources is not a violation. The onus is on you to explain why he is part of a “techno cult of neurodivergent losers” and not use that as a ad hom.

AI requires energy and at present we are dependent on a declining base of fossil fuels for the vast portion of our energy. No energy, no AI. We’re at the limits to growth, with energy constraints one of the limits humanity faces. Apocalyptic? It all depends on how humanity -various segments of humanity, that is– will react to hitting these limits -and if these segments ever realize that’s what’s going on. Mine is a purely secular view, I believe.

What happened to the planet known as Apollo? Also known as Abel.

It is in pieces. They still occupy the orbit between Mars and Jupiter.

Why does Venus rotate the wrong way, yet is slowly reversing that spin?

Neptune has the fastest winds known in the solar system, yet is also the coldest planet.

Electromagnetism over distances is Alternating Current. Reversal of polarity happens every 530 years or so.

To correct its calendar, Rome added two months increasing the 304 days to 364. Decem ber was the tenth month, it became the twelth.

History has added 1000 years to our story. Lyellism just increased it a million times.

Is this post AI generated?

In our history when we thought about an apocalypse, the idea that came to mind was the Four Horsemen – conquest, war, famine, and death. But in the past three quarters of a century, there has been a shift where we have realized that we could create our own apocalypses. Nuclear war was the first followed by the idea of a nuclear winter. Then in the past few decades you have climate change, pandemics, dystopian governments, etc. so that the number of potential apocalypses actually increased. But more to the point, we are actually creating them and there is nothing natural about them. They are all on us.

It seems to me that the influence of zombie movies and games is responsible for the overuse of the term apocalypse.

Ah yes, that other Z. Some years back i learned that a forum i used to frequent had banned the term, as it was often used as a euphemism for rioting. In particular if the person was brandishing their “zombie survival kit” that included high caliber weapons etc.

What Should We Fear Most? The feamongers. Also, Russia, and China, and communism.

ANd you are not a fearmonger then?

The only reason to fear “Russia, and China, and communism” is through excessive consumption of US establishment propaganda. Stop doing it.

Well said, & so true.

Am i the only one left wondering what a “feamonger” is?

-monger, denoting a dealer or trader in a specified commodity.

Fea… Finite element analysis?

Dealer or trader in finite element analysis.

This is all getting too heady for me.

It may also be useful, especially in the context of Israel’s war on Gaza, to consider the antecedent of “apocalypse” in the Greek bible: the “day of the LORD” (yom YHWH) in the Hebrew bible.

First Isaiah is usually credited with being the first prophet to use the phrase in Isaiah 2:12.

This Isaiah passage seems directed against all humanity:

Isaiah 2:17.

Elsewhere in the Hebrew bible, the “day of the LORD” impacts Israelites and goyim, or in some cases, faithful believers and sinners in starkly different ways. For example, in Jeremiah 30, the prophet of the Babylonian destruction of Jerusalem depicts a “day of the LORD” that follows the destruction of the temple when YHWH “breaks the yoke” that has enslaved “Jacob” and brings to an end their suffering in a new Messianic age when YHWH will raise up a new David. (Jer. 30:8-9).

The short book of Zephaniah, which is entirely about the “day of the LORD,” exemplifies the ambiguous nature of Yom YHWH For Jerusalem and its rulers, there will be terror and destruction:

Zephaniah 1:8-9.

But this death and destruction is in reality a purification process that will result in Jerusalem’s exaltation above the nations:

Zephaniah 3:9-13.

And YHWH will go on to destroy the goyim who have abused and often conquered the weak nations of Israel and Judah like Philistia and Assyria. (Zeph. 2)

The prophets’ “day of the LORD,” and it is a prophet’s theme not found in the histories, is the day that YHWH sets things straight. Much of his wrath will be directed against the unfaithful Israelites, but ultimately, YHWH’s people will be cleansed, redeemed and exalted above the nations.

Given the history of Israel and Judah, in which these two small nations failed to maintain their independence under assault from the great empires of Egypt, Assyria and neo-Babylonia that surrounded them, the “day of the LORD” meant both a time of judgment against YHWH’s people for their chronic unfaithfulness and a time of revenge against the nations that had abused them. It was ultimately a message of consolation for the powerless faithful within those two nations who were suffering at the hands of foreign invaders along with the elites who were getting what they deserved. Ironically, the message of consolation and exaltation has been taken by those in power in today’s Israel to justify their slaughtering of innocent goyim in preparation for the Messiah’s arrival and Israel’s exaltation.

It’s a sadistic, hateful revenge porn fantasy of people who have very little power but really, really would like to have lots of it

How look forward to everyone else being given into their hands as their slaves.

All the whole purity Obsession and ranting about unfaithfulness does is making Yahweh look even more like a controlling, paranoid wifebeater.

It also should be pointed out that there isn’t much of anything resembling free will in that book.

Even when they are unfaithful, YHWH has nobody to blame but himself.

The new testament of course doubles down on that, with almost everyone being chosen for damnation from eternity and so on.

There’s also that nice Part where the Chosen who are “saved” still can/have to Look at those who are burning and eaten by the worms forever and ever.

Though this serves more as intimidation, it was only the later catholics who turned it into a füll blown excercise in pure sadism, where watching the eternal torture of the damned was supposed to be one of the greatest joys of heaven.

It certainly helped put this foundational believe that doing unimaginably horrible things can not only be fully justified and moral but even an act of love and compassion, at least as long as the right ones are doing it right at the center of western moral thinking where it remains deeply rooted.

In a way it certainly seems like progress to me that Apocalypse became more something horrible to avoided than something wished for.

Though the later could still perhaps be said to live on in various pseudo secularized forms as well.

Certainly with some of the post humanists and singularitarians, though of course those are often pretty much openly religious.

Even if they think they will have to create their God themselves or at least helping to ensure He will be Born.

They certainly share with their more conventionally theistic brethren the idea of a theocentric mortality that at least CAN very easily and completely divorced from any question of actual,concrete human wellbeing and even survival.

Those things being secondary to some higher, “transcendental” value or “truth” is of course also omnipresent in most western worldviews, no matter how secular..

An apocalypse is anything that forces North Americans and Europeans to give up their current lifestyles and standards of living based on continuous burning of fossil fuels.

Nuclear war is also a climate issue, since nuclear winter (with its resulting mass starvation) would be another human caused climate catastrophe. And the nuclear threat is unknowable because accidents and changes in leadership of countries with nuclear warhead equipped missiles could have an outsized effect.

Speaking of mass starvation, threats to our food supply from current agricultural practices not being resilient in the face of environmental changes (pests, plant diseases, livestock diseases, water table changes, etc.) could be another source of apocalypse. And there is another class of threats involving toxic chemicals saturating the environment, where effects may already be becoming evident in lower human fertility and lower life expectancies.

I would add a reference or two about this topic.

First of all is “Armageddon” by Bart Ehrman, one of our best Ancient Greek scholars in the USA.

This book is not really an exegesis, he does not delve too much into the Greek text, but it is a very thorough analysis of Revelation and its cultural significance. It is an extremely complete discussion and touches on most if not all of the points of the above article.

Ehrman briefly mentions another book by amazingly none other than DH Lawrence. After he got through with all his novels like Sons and Lovers, his very last book published in the immediate aftermath of the Stock Market Crash of 1929 and the onset of the Great Depression was called “Apocalypse”. It is Non Fiction. And one of the most amazing discussions of the true meaning of Revelation I have ever read. I have thought a few times over the years of why this book is not more known on this blog. In essence, he convincingly argues his point that Revelation is not so much about ultimate good vs ultimate evil – BUT it is about wealth and dominion and who gets to control it, how, and the consequences. It is an amazing read.

For an exegesis of the Apocalypse of John, I’d recommend Adela Collins‘ The Combat Myth in the Book of Revelation along with her other writings about apocalypse. When she taught at U. of Chicago Div School in the 90s, she was a member of the Jesus Seminar.

I guess in the end the original curse of the apple was to make the ape reflect on its predicament.

I always as well go further back in my own mind to thinking that ‘apocalypse’ can break down to “apo – calypso” which is the Greek phrasing for ‘from the island ‘ as Odysseus sets out on his voyage homeward. Which takes in the element of a homeward travel rather than absolute disaster, although that threatens our hero at every point on the journey. I know, that’s not the general understanding; it just sounds that way to my ears.

I also put the ‘revelation’ aspect to myself as, my having been born in the islands of New Zealand, there is a deep maori attitude towards the ocean shoreline, which includes the land that is ‘revealed’ when the tide goes out, I think designated as ‘ara moana’. Which has the element of extreme danger as a tsunami unfolds.

It is a very loaded word, triggering both apprehensive fear and the need to know what is happening in order to be safe.

The concept of Apocalypse doesn’t exist in traditional Chinese culture. Chinese people don’t think there will be an end of the world or the universe. In traditional Chinese values, the Sky and the way it exists is eternal. It always follows a regular, usual, everlasting path and will not change because of human society (天行有常,不为尧存,不为桀亡).

However, the Indians do enjoy devastations:

http://puneresearch.com/media/data/issues/5c0f6fde1c6db.pdf

A preference for a cyclical understanding of time rather than a teleological one.

Eternal time does not of itself imply teleology. For instance, shit might happen eternally, and so on.