Yves here. This post usefully provides an analysis of the degree to which trade relations have changed as a result of Western sanctions and tariffs. It shows that patterns started shifting after 2018, as in a year after Trump implemented tariffs on China. Note that after the global financial crisis, there was a lot of hand-wringing among multinationals about the need to simplify supply chains and shift more production closer to final sales markets, but this post suggests not much actually happened.

The post is nevertheless timely because the Biden Administration is doubling down with China:

White House announces new anti-China tariffs:

🚗 Electric vehicles: from 25% to 100%

🔋 EVs batteries: from 7.5% to 25%

🌞 Solar cells: from 25% to 50%

🏭 Steel and aluminum: from 0%-7.5% to 25%#EnergyTransition #EVshttps://t.co/gSnLerBfz0— Javier Blas (@JavierBlas) May 14, 2024

One thing about this post is the remarkable lack of agency, starting with the first sentence: “There has been a rise in trade restrictions…” Another striking feature is the use of MBA-evocative intended-to-become buzzwords like “slowbalification” and sadly established ones like “friend-shoring” and “de-risking.” “De-risking” is particularly obfuscatory. How does the EU dropping cheap Russian gas reduce risk….unless you admit those dastardly Rooskies had no reason to blow up their own pipeline and have Europe shift to high price LNG, which increases economic risk by increasing costs. The piece kinda-sorta acknowledges that business margins are taking hits, but not the severe damage of slow motion European de-industrialization. However, in a highly coded manner, it suggests that former exports may still be getting there via other routed.

So I am left wondering if this sort of soft self-censorship has become endemic, at least among European economists whose areas of expertise impinge on the new Cold War.

By Costanza Bosone, PhD candidate University Of Pavia; PhD candidate University School Of Advanced Studies (IUSS) – Pavia; ;Ernest Dautović, Supervisor European Central Bank; Michael Fidora, Senior Lead Economist European Central Bank; and Giovanni Stamato, Consultant European Central Bank. Originally published at VoxEU

There has been a rise in trade restrictions since the US-China tariff war and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. This column explores the impact of geopolitical tensions on trade flows over the last decade. Geopolitical factors have affected global trade only after 2018, mostly driven by deteriorating geopolitical relations between the US and China. Trade between geopolitically aligned countries, or friend-shoring, has increased since 2018, while trade between rivals has decreased. There is little evidence of near-shoring. Global trade is no longer guided by profit-oriented strategies alone – geopolitical alignment is now a force.

Since the global financial crisis, trade has been growing more slowly than GDP, ushering in an era of ‘slowbalisation’ (Antràs 2021). As suggested by Baldwin (2022) and Goldberg and Reed (2023), among others, such a slowdown could be read as a natural development in global trade following its earlier fast growth. Yet, a surge in trade restriction measures has been evident since the tariff war between the US and China (see Fajgelbaum and Khandelwal 2022) and geopolitical concerns have been heightened in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, with growing debate about the need for protectionism, near-shoring, or friend-shoring.

The Impact of Geopolitical Distance on International Trade

Rising trade tensions amid heightened uncertainty have sparked a growing literature on the implications of fragmentation of trade across geopolitical lines (Aiyar et al. 2023, Attinasi et al. 2023, Campos et al. 2023, Goes and Bekker 2022).

In Bosone et al. (2024), we present new evidence and quantify the timing and impact of geopolitical tensions in shaping trade flows over the last decade. To do so, we use the latest developments in trade gravity models. We find that geopolitics starts to significantly affect global trade only after 2018, which, timewise, is in line with the tariff war between the US and China, followed by the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Furthermore, the analysis sheds light on the heterogeneity of the effect of geopolitical distance by groups of countries: we find compelling evidence of friend-shoring, while our estimates do not reveal the presence of near-shoring. Finally, we show that geopolitical considerations are shaping European Union trade, with a particular focus on strategic goods.

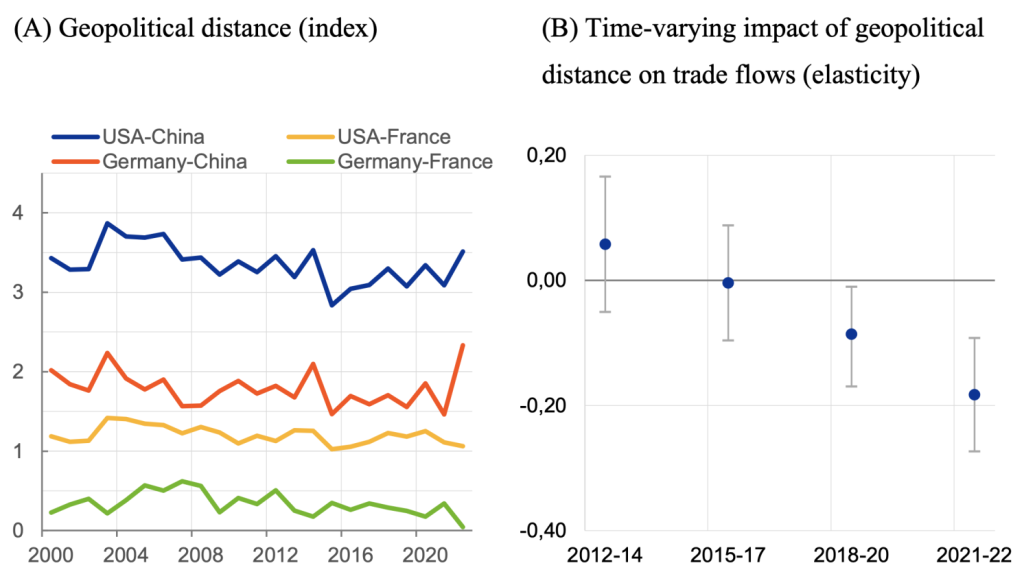

In this study, geopolitics is proxied by the geopolitical distance between country pairs (Bailey et al. 2017). As an illustration, Figure 1 (Panel A) plots the evolution over time of the geopolitical distance between four country pairs: US-China, US-France, Germany-China, and Germany-France. This chart shows a consistently higher distance from China for both the US and Germany, as well as a further increase in that distance over recent years.

Geopolitical distance is then included in a standard gravity model with a full set of fixed effects, which allow us to control for unobservable factors affecting trade. We also control for international border effects and bilateral time-varying trade cost variables, such as tariffs and a trade agreement indicator. This approach minimises the possibility that the index of geopolitical distance captures the role of other factors that could drive trade flows. We then estimate a set of time-varying elasticities of trade flows with respect to geopolitical distance to track the evolution of the role of geopolitics from 2012 to 2022. To the best of our knowledge, we cover the latest horizon on similar studies on geopolitical tensions and trade. To rule out the potential bias deriving from the use of energy flows as political leverage by opposing countries, we use manufacturing goods excluding energy as the dependent variable. We present our results based on three-year averages of data.

Figure 1 Evolution of geopolitical distance between selected country pairs and its estimated impact on bilateral trade flows

Notes: Panel A: geopolitical distance is based on the ideal point distance proposed by Bailey et al. (2017), which measures countries’ disagreements in their voting behaviour in the UN General Assembly. Higher values mean higher geopolitical distance. Panel B: Dots are the coefficient of geopolitical distance, represented by the logarithm of the ideal point distance interacted with a time dummy, using 3-year averages of data and based on a gravity model estimated for 67 countries from 2012 to 2022. Whiskers represent 95% confidence bands. The dependent variable is nominal trade in manufacturing goods, excluding energy. Estimation performed using the PPML estimator. The estimation accounts for bilateral time-varying controls, exporter/importer-year fixed effects, and pair fixed effects.

Sources: TDM, IMF, Bailey et al. (2017), Egger and Larch (2008), WITS, Eurostat, and ECB calculations.

Our estimates reveal that geopolitical distance became a significant driver of trade flows only since 2018, and its impact has steadily increased over time (Figure 1, Panel B). The fall in the elasticity of geopolitical distance is mostly driven by deteriorating geopolitical relations, most notably between the US and China and more generally between the West and the East. These reflect the effect of increased trade restrictions in key strategic sectors associated to the COVID-19 pandemic crisis, economic sanctions imposed to Russia, and the rise of import substituting industrial policies.

The impact of geopolitical distance is also economically significant: a 10% increase in geopolitical distance (like the observed increase in the USA-China distance since 2018, in Figure 1) is found to decrease bilateral trade flows by about 2%. In Bosone and Stamato (forthcoming), we show that these results are robust to several specifications and to an instrumental variable approach.

Friend-Shoring or Near-Shoring?

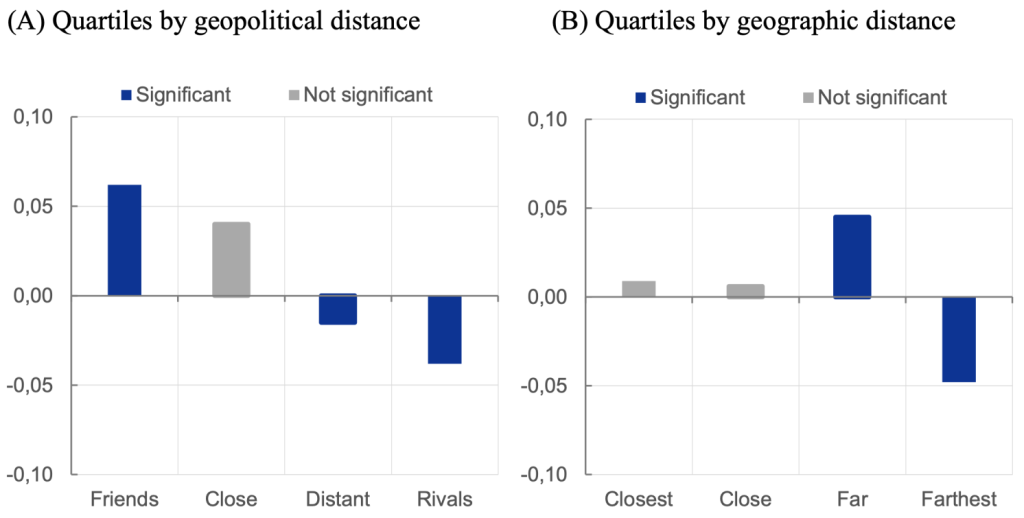

Recent narratives surrounding trade and economic interdependence increasingly argue for localisation of supply chains through near-shoring and strengthening production networks with like-minded countries through friend-shoring (Yellen 2022). To offer quantitative evidence on these trends, we first regress bilateral trade flows on a set of four dummy variables that identify the four quartiles of the distribution of geopolitical distance across country pairs. To capture the effect of growing geopolitical tensions on trade, each dummy is equal to 1 for trade within the same quartile from 2018 and zero otherwise.

We find compelling evidence of friend-shoring. Trade between geopolitically aligned countries increased by 6% since 2018 compared to the 2012–2017 period. Meanwhile, trade between rivals decreased by 4% (Figure 2, Panel A). In contrast, our estimates do not reveal the presence of near-shoring trends (Figure 2, Panel B). Instead, we find a significant increase in trade between far-country pairs, offset by a relatively similar decline in trade between the farthest-country pairs. Overall, shifts toward geographically close partners are less pronounced than toward geopolitically aligned partners.

Figure 2 Impact of trading within groups since 2018 (semi-elasticities)

Notes: Estimates in both panels are obtained by PPML on the sample period 2012–2022 using consecutive years. Please refer to Figure 1 for details on estimation. The effects on each group are identified based on a dummy for quartiles of the distribution of geopolitical distance (panel A) and on a dummy for quartiles of the distribution of geographic distance (panel B) across country pairs. The dummy becomes 1 in case of trade between country pairs belonging to the same quartile since 2018. A semi-elasticity corresponds to a percentage change of 100*(exp()-1).

Sources: TDM, IMF, Bailey et al. (2017), Egger and Larch (2008), WITS, Eurostat, CEPII, and ECB calculations.

Evidence of De-Risking in EU Trade

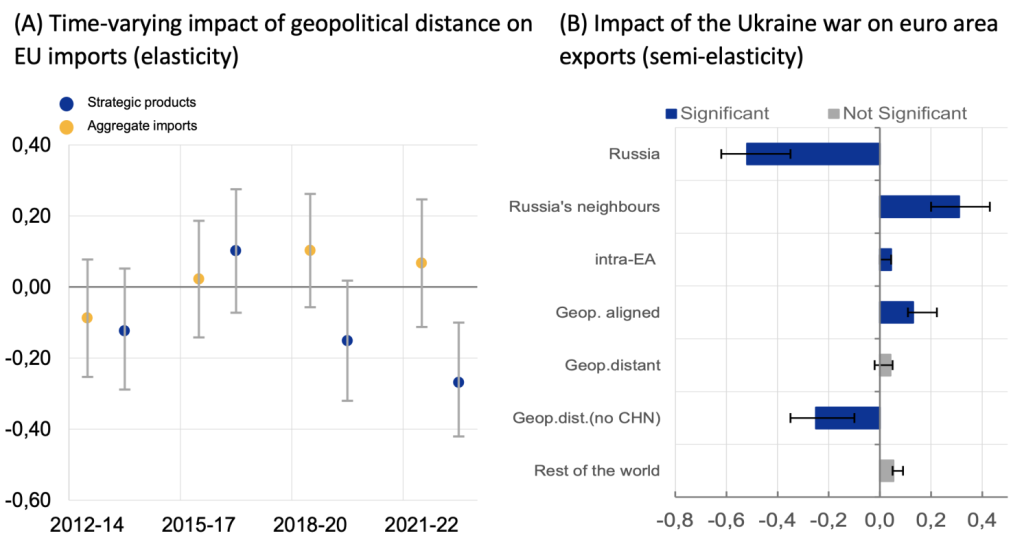

The trade impact of geopolitical distance on the EU is isolated by interacting geopolitical distance with a dummy for EU imports. We find that EU aggregate imports are not significantly affected by geopolitical considerations (Figure 3, Panel A). This result is robust to alternative specifications and may reflect the EU’s high degree of global supply chain integration, the fact that production structures are highly inflexible to changes in prices, at least in the short term, and that such rigidities increase when countries are deeply integrated into global supply chains (Bayoumi et al. 2019). Nonetheless, we find evidence of de-risking in strategic sectors. 1 When we use trade in strategic products as the dependent variable, we find that geopolitical distance significantly reduces EU imports (Figure 3, Panel A).

Figure 3 Impact of geopolitical distance on EU imports and of the Ukraine war on euro area exports

Notes: Estimates in both panels are obtained by PPML on the sample period 2012–2022. Panel A: Dots represent the coefficient of geopolitical distance interacted with a time dummy and with a dummy for EU imports, using 3-year averages of data. Lines represent 95% confidence bands. Panel B: The sample includes quarterly data over 2012–2022 for 67 exporters and 118 importers. Effects on the level of euro area exports are identified by a dummy variable for dates after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Trading partners are Russia; Russia’s neighbours Armenia, Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, and Georgia; geopolitical friends, distant, and neutral countries are respectively those countries that voted against or in favour of Russia or abstained on both fundamental UN resolutions on 7 April and 11 October 2022. The whiskers represent minimum and maximum coefficients estimated across several robustness checks.

Sources: TDM, IMF, Bailey et al. (2017), Egger and Larch (2008), WITS, Eurostat, European Commission, and ECB calculations.

We conduct an event analysis to explore the implications of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on euro area exports. We find that the war has reduced euro area exports to Russia by more than half (Figure 3, Panel B), but trade flows to Russia’s neighbours have picked up, possibly due to a reordering of the supply chain. Euro area exports with geopolitically aligned countries are estimated to have been about 13% higher following the war, compared with the counterfactual scenario of no war. We find no signs of euro area trade reorientation away from China, possibly reflecting China’s market power in key industries. However, when China is excluded from the geopolitically distant countries, the impact of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on euro area exports becomes strongly significant and negative.

Concluding Remarks

Our findings point to a redistribution of global trade flows driven by geopolitical forces, reflected in the increasing importance of geopolitical distance as a barrier to trade. In this column we review recent findings on geopolitics in trade and their impact since 2018, the emergence of friend-shoring rather than near-shoring, and the interactions of strategic sectors with geopolitics in Europe. In sum, we bring evidence of new forces that now drive global trade – forces that are no longer guided by profit-oriented strategies alone but also by geopolitical alignment.

_______

I guess the 2008 GFC was the high water mark of international cooperation. Since then, the world has split back into two rival poles and the emergence of a new, non-aligned bloc.

First came the eviction of Russia from the G8, with problems beginning in 2012 with the Snowden asylum. Then came the Maidan, Russiagate, and now the war. This helped peel China away, too.

Covid was another giant step in the process with the West using their ‘vaccines’ as a geopolitical weapon. Chinese and Russian vaccines were not recognised and so exchange plummeted.

Now the rift is almost complete. On the one hand, you have the genocidaire west ; on the other, BRICS. The non-aligned world is the biggest there has been since the cold war, and most want to join BRICS.

“The non-aligned world is the biggest there has been since the cold war, and most want to join BRICS.”

April 15, 2024

BRICS = Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa.

BRICS+ = Egypt, Ethiopia, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates and Iran

are now full members of BRICS, while Algeria is a partial BRICS or New

Development Bank member.

Share of World GDP, 2023

Brazil ( 2.3)

China ( 19.1)

India ( 7.6)

Russia ( 2.9)

South Africa ( 0.6)

https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2024/April/weo-report?c=223,924,532,534,546,922,199,&s=PPPGDP,PPPSH,&sy=2007&ey=2023&ssm=0&scsm=1&scc=0&ssd=1&ssc=0&sic=0&sort=country&ds=.&br=1

Algeria ( 0.4) *

Egypt ( 1.0)

Ethiopia ( 0.2)

Iran ( 1.0)

Saudi Arabia ( 1.3)

United Arab Emirates ( 0.5)

* Member of BRICS Bank

Hate to break it to you, but there’s no such thing as BRICS, except in the addled minds of journalists who think snazzy acronyms are more important than actually understanding complex geopolitical relationships.

India and China, the two biggest economies of the so-called BRICS, absolutely loathe each other and are one misstep on a remote Himalayan mountaintop away from a nuclear exchange.

While both are nominally allies of Russia, it’s no secret that China views its relationship with Russia as purely an extractive one, a ready source of cheap raw materials to feed its economy and absorb its exports. Some Chinese have even started referring to Vladivostok by their Chinese name for it: Hǎishēnwǎi, which any neighbor of China can tell you, is an ominous sign.

India’s relationship with Russia is actually somewhat more genuine, forged over decades when Russia was their main great power supporter on the world stage and the largest and most reliable source of their arms imports. But India is increasingly aligning itself with the West (e.g. the Quad, and mainly to counterbalance China) and while some residual closeness remains, most people on both sides feel this relationship is close to running its course.

And Russia is caught in the middle, trying to maintain alliances with both countries while each demands that Russia renounce the other one.

Brazil and South Africa are literally on different continents from each other and the rest of the BRICS, and are so far down the priority list of each of the other countries (and vice-versa) that to include them as some part of grand alliance is laughable.

I’m not joking when I say that if the names of these countries didn’t happen to make a catchy acronym in English, no journalist would mention them in the same breath.

Russia is a military superpower and this is why it is imporant for China. China is an economic superpower and this is why it is imporant for Russia. It is a symbiotic relationship in the context of the current world situation. Under different contexts that may be not true.

Thanks to its military strength Russia was able to undo all the US schemes in the middle East ( Arab spring wars ) and Africa ( instability in the Sahel).

The instability in Africa was targeting China. The US strategists were obsessed with the rising China but the instability they created in the Sahel weakened their influence over the local regimes.

The Cure for that instability was provided by russian military strength and the geopolitical landscape in the Sahel changed overnight.

The same can be said for the situation in South America where the US were unable to do anything against Venezuela thanks to the military strenght of Russia and economic power of China.

Brics has to be seen as a coordination platform for the transition towards a new world order. That the relation between between China and India is complicated makes more sens for the existence of that platform to bring together these two big countries.

some misconceptions in this post I need to address. First, BRICS started off as a catchy acronym by Goldman’s Jim O’Neill but it absolutely is a real organization with membership, rules, summits, etc. Many countries do have some rivalry but the same can be said of Turkiye and the rest of NATO.

Second, there is ample evidence that the Sino-Russian relationship is anything but transactional, but I have no doubt that this is a framework that American leadership (mis)understand things. For both of these countries the USA is an existential threat. It is the number one threat. Not climate change or pandemics, but the USA. To defeat the US, they must both be strong so their prerogative is to strengthen each other. American thinkers, incapable of looking out past the next quarters, cannot understand this. To them, if Russia is under economic pressure from the west, it’s rational for China to strip Russia of her assets. For China, this would not be rational. The need for a strong Russia is greater than the need for assets and the leadership of both countries understands this. Whatever disputes they may have over Siberia and Kamchatka can be deferred until after the US is broken up. For now, if China needs extra fresh water Russia will be very happy to transport its surpluses at a discount. Same goes for oil and gas, and Chinese technology in the other direction.

I think you may be a victim of propaganda put out by our media.

China and India are in no way close to nuclear war. Just because a few hundred soldiers had skirmishes with each other using sticks and stones does not mean they are close to war. The two countries don’t loathe each other as you imply. Politically it is popular to whip up hate of China by the current administration in India. There is a lot of trade between the two. As to QUAD, it’s not going anywhere.

Russia and China have had a better relationship than Russia and the US. Why call trade of raw materials extractive when China is doing the same with other countries? Thanks to the West making the world’s manufacturer, China needs more raw materials to feed the demand.

BRICS is slowly become a reality and the US Dollar is losing its popularity due to sanctions. While China is reluctant to use their currency as a reserve currency, there is a move to use gold to solve trade imbalances between countries.

“it’s no secret that China views its relationship with Russia as purely an extractive one, a ready source of cheap raw materials to feed its economy and absorb its exports. Some Chinese have even started referring to Vladivostok by their Chinese name for it: Hǎishēnwǎi, which any neighbor of China can tell you, is an ominous sign”

This is just innuendo, without any proof being supplied. Your description of the China / Russia relationship is news to me, despite serious perusal of all the relevant information I can find. In reality, China and Russia are aware of the very plain fact that the US would like to dismantle and dominate both of them, (preferably separately, although in practice the ineptitude of the US has thrown them together,) and are keenly aware that the more they engage with and support each other, the less likely will be any US success. Additionally, Russia is still ahead of China in many highly technical areas, such as civil aviation and space technology, and China knows that.

April 15, 2024:

G7 counted for 30.1% of world GDP in purchasing-power-parity terms

BRICS+ counted for 36.9% of world GDP in PPP terms

BRICS+ GDP was 22.6% greater than G7

The study by Kenneth Rogoff and Carmen Reinhart, 800 Years of Financial Crises, found that high levels of international capital flows were strongly correlated with serious financial crises.

Unless you have largely balanced trade, a condition pretty much never observed in nature, high level of international trade produce high levels of international capital flows.

Friend-shoring without near-shoring ==> vassals.

None of this need have happened if FDR, Morgenthau and White had permitted the re-balancing of international trade by means of bancor and Keynes’s clearing union, and if the ITO had not failed in 1947.

By insisting on maintaining paramountcy the US wound up losing its gold and balances, and then seeing its wider economic position subverted, and now wants to resolve its deficits in ever more dangerous ways. More generally, it has now dawned on it (especially since Yellen’s abortive mission) that US policy has drawn China and Russia together in an alliance which is now nearly indissoluble.

In 1969 the new NSA Kissinger remarked “If there should be a Eurasia, either controlled from Moscow or effectively dominated by Moscow, we would then find that all other parts of the world…would fall ideologically in that order”. Therefore, the US could survive only “by a degree of regimentation that would leave dramatic transformations” and that its “ability to influence events in the world would gradually vanish”. “Never could we survive as an island in a totally hostile environment” (taken from pp. 20-21 here: https://www.cornellpress.cornell.edu/book/9781501774119/disruption/#bookTabs=1)

By driving China and Russia together, the US has created a new geopolitical force with a tremendous ‘gravitational pull’ for much of the rest of the world that is perhaps almost irresistible. The US can only counteract that pull by thrashing around in Ukraine and the Middle East, by means of punitive tariffs (which will stoke inflation at home) and by extorting wealth from European consumers. Specifically, it has to double down on hegemony in order to conserve the exorbitant privilege of the dollar, lest the US be drowned in its own liabilities, but hegemony is increasingly expensive and its liabilities have continued to grow as a result. The tragic paradox is that those very stratagems which are intended to prevent US isolation and insolvency might make those outcomes that much more inevitable.

from yer mouth, to god’s ear,lol.

it aint like it was hard to see this coming, after all.

i’m just surprised that it took this long for a relatively peer country to gather enough smash to actually challenge the hegemon.

Yes, the NewSpeak jargon is amusing, yet typical. The new phase of economic warfare against China will only make US domestic goods more expensive. These tariffs and “sanctions” will not help the US worker at all. The US cannot compete in manufacturing because the overhead costs and built-in economic rent are much too high. Reducing wages to subsistence level has not, and will not revive US manufacturing.

This geopolitical factor may partly be a convenient, cheap election-year stunt to distract folks from the 10s of billions given away to Ukraine, Israel etc. while the US population get extorted for health care, housing, food, energy and the basic necessities of life. Distract the D party faithful into voting for Genocide Joe because he cares about US workers and cares about the environment. This is only going to make solar and “green energy” equipment more expensive. They clearly don’t give a toss about the environment or climate issues, just a cynical political stunt. Just like Genocide Joe might limit the weapons shipments to Israel, it’s just BS as usual.

The US can huff and puff, threaten, ‘sanction’, etc. but if the Cold War between the US and China intensifies, and full-blown economic blockades are imposed, the US economy will likely fare far worse than China’s. This potentiality has serious implications for balance of trade and the value of the dollar as well.

I’d like to see them do a new analysis of the Houthi blockade of Suez. That might be too much of a hot-potato for them to ‘splain away.

How does the EU dropping cheap Russian gas reduce risk

No, you have got it wrong! Yesterday Rishi Sunak explained that Putin had cut off gas supplies and that had had a devastating impact on people’s lives and threatened EU energy security.

They really think the electorate have the memory of a goldfish

https://twitter.com/NationalIndNews/status/1789995608238940522

geez:

“The trade impact of geopolitical distance on the EU is isolated by interacting geopolitical distance with a dummy for EU imports. We find that EU aggregate imports are not significantly affected by geopolitical considerations (Figure 3, Panel A). This result is robust to alternative specifications and may reflect the EU’s high degree of global supply chain integration, the fact that production structures are highly inflexible to changes in prices, at least in the short term, and that such rigidities increase when countries are deeply integrated into global supply chains (Bayoumi et al. 2019). Nonetheless, we find evidence of de-risking in strategic sectors. 1 When we use trade in strategic products as the dependent variable, we find that geopolitical distance significantly reduces EU imports (Figure 3, Panel A).”

so…globalism was a bad idea, after all?

just like hoi polloi like meself were saying in the mid-90’s?

(before i undertook the study of economics)

do these folks ever accept responsibilty for their f&ckups?

or is that just for us little people?

Please forgive me, but economic or trade relations between the US and China began to openly change in April 2011 with the Congressional passing and Obama signing of the Wolf Amendment which cut off China from working on space exploration and program development with NASA. The intent was to limit China technology development and that intent never changed only became more intense to what the Washington Post explained was the intent of Trump to force China to limit manufacturing development. Biden has simply added to the force of the Trump trade war. The point now is evidently to prevent any further economic development of China.

Biden has indeed prevented the passing in the United Nations of an affirmation the nations have a right to economic development, but the intent was there from the Obama pivot to Asia or the Pacific and the express intent to “contain” China.

Amfortas: the Hippie: The perps are never held to account, you are right, taxes and the law are only for the little people.

“Globalism” is their word and it’s very inaccurate: the vast global majority are telling the empire to f-off. The Anglo-American Zionist imperial oligarchy fancy themselves as masters of the globe and universe – typical arrogance and hubris.

Those scrappy, badass “houthis” look like they have chased the US/UK navy out of the Red Sea https://sputnikglobe.com/20240514/us-destroyer-quits-red-sea-sails-home-as-houthis-warn-of-escalation-enemy-cant-imagine-1118423160.html

It’s all about the desperate, reckless declining empire trying to maintain their vassals and spheres of influence. But they forgot to crack open a history book, all this BS rhymes. Let’s just hope they don’t throw a tantrum and kick over the whole sand castle, and ruin it for everybody (like the privileged, spoiled brats that they are)

re held to account, I was just thinking on my walk about corporate persons and how they never die, like a real person would, and so never face the reckoning the real person must. I’d say every 80 years retract the corporate charter and tax the company like heirs would be taxed by valuing then taxing the transition and breaking up various parts reducing concentration. It’s only fair, but fair is where you judge pigs…or so I heard on the sports tv…

It’s obvious they have no plan B other than nukes, and that’s what has me quaking in my boots these days.

Also, quakeing.

Who really knows what is going on?

Where is the wealth moving to?

“Nukes” threaten real wealth.

Fear keeps the peasants in thrall.

Absolutely. Will second that. India and China have been crossing swords forever and even had a short war in the 1960s when India was under Nehru. The Chinese won that war but retreated voluntarily after coming across the borders a long way. A war with Pakistan is more likely.