Yves here. I look forward to EU and UK readers to chime in, but this posts gives an interesting perspective of what seems to be driving the increasingly rebellious posture among European voters towards the EU project. The short version is James Carville’s “It’s the economy, stupid.” Here, that means regions that are lagging compared to others, particularly those that seem to have poor prospects for turning things around.

And it’s not as if voters in these declining areas can be stereotyped as deplorables, as they are in the US. The authors point out that they often were once prosperous. And Europe being Europe, I would imagine many of these falling sections have universities or at least technical colleges, meaning there is still a decent cadre of the well educated.

Another noteworthy feature of this article is the lack of agency as to how this sorry state of affairs developed. EU budget rules? Kick the can approaches to the financial crisis bank losses? The failure to move to more Eurozone level spending to buffer national and regional disparities (thank you Germany and friends)? Not that it could have been stopped, but the impact of the destruction of NordStream2 and the other anti-Russian energy measures? Admittedly, the authors do recommend policies to bolster economic activity in these laggard areas. But how much will be possible given that Europe seems to be moving in guns over butter mode?

Nevertheless, one can only say so much in a compact article and this one is a useful addition.

By Andrés Rodríguez-Pose; Lewis Dijkstra, Urban and Head of the Territorial Analysis Team, Joint Research Centre European Commission; and Hugo Poelman, Senior Assistant, DG Regional and Urban Policy European Commission. Originally published at VoxEU

Political discontent has been on the rise across Europe. This column draws on the concept of regional ‘development traps’ to examine the complex relationship between regional economic stagnation and increasing Euroscepticism within the EU. Regions mired in long-term economic decline, with limited economic prospects and a declining standard of living compared to more prosperous regions, are ensnared in a cycle of deep political discontent and are driving the rise in support for Eurosceptic parties. Addressing these economic disparities is essential for reducing Eurosceptic sentiments and ensuring the cohesion of the European project.

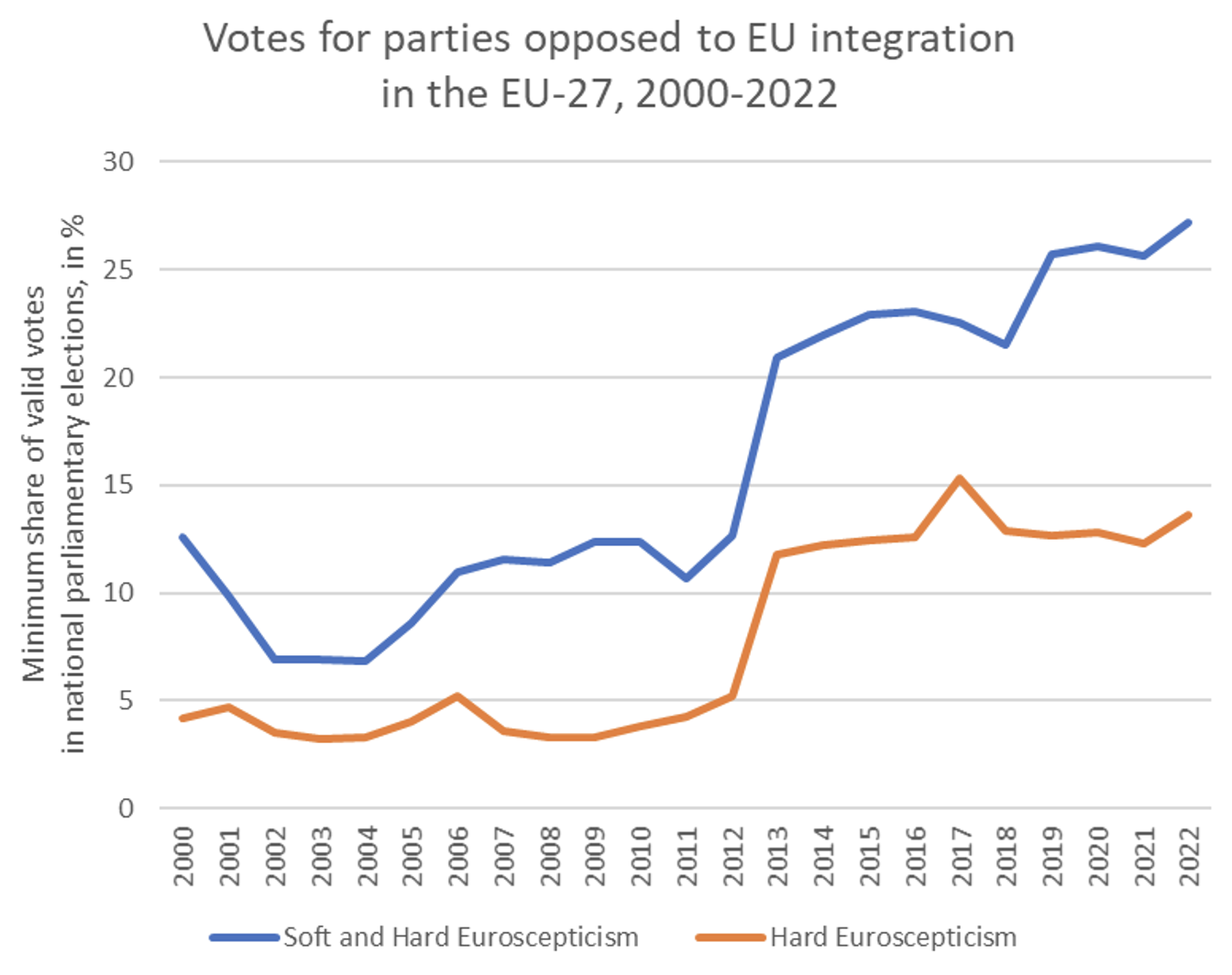

Political discontent has been on the rise across Europe. A manifestation of this dissatisfaction is the surge in support for Eurosceptic parties, particularly following the 2008 financial crisis. Voter disaffection with the EU is evident from the rising shares of support for both ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ Eurosceptic parties (Greven 2016, Zakaria 2016, Hopkin 2020, Dijkstra et al. 2020), which has grown from a mere 4% in 2002 to 27% in 2022. Identity crises and cultural conflicts are significant driver of this rise in discontent (Norris and Inglehart 2019, Hopkin 2020). However, economic decline, particularly in regions of Europe previously noted for their prosperity, is further fuelling this trend (Becker et al. 2017, Rodríguez-Pose 2018, Fetzer 2019, Lenzi and Perucca 2021, McKay et al. 2021).

In a new article (Rodríguez-Pose et al. 2024), we build on Diemer et al.’s (2022) concept of ‘development traps’ to analyse the extent to which economic stagnation at a regional level in the EU is driving discontent and stoking Euroscepticism. We find that Euroscepticism is thriving in places that become stuck in long-term development traps and that the longer the period of stagnation, the stronger the support for parties opposed to European integration.

The Rise of Euroscepticism

Two decades ago, Euroscepticism was a marginal phenomenon. It was confined to fringe parties – such as the French National Front, the Danish Progress Party, or the Austrian Freedom Party, among others – that, at the time, struggled to survive at the extremes of the political spectrum. However, Euroscepticism is no longer marginal and many of those parties and new ones are now strong contenders for power. ‘Hard’ Euroscepticism, denoting outright opposition to EU integration, has regularly garnered almost 15% of the vote in national legislative elections since the mid-2010s (Figure 1). When ‘soft’ Euroscepticism – involving strong opposition to certain EU policies rather than the outright demise of the EU – is also considered, votes for Eurosceptic parties reached more than 27% of the total in national actions by 2022 (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Votes for parties opposed to EU integration in national parliamentary elections in the EU-27, 2000-2022

Source: DG REGIO calculations based on the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES) (Jolly et al., 2022) and DG REGIO data collection.

Note: Hard Euroscepticism is defined as a score of 2.5 or lower on the EU-position index on the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES). Soft and hard Euroscepticism is defined as a score of 3.5 or lower on the EU-position index.

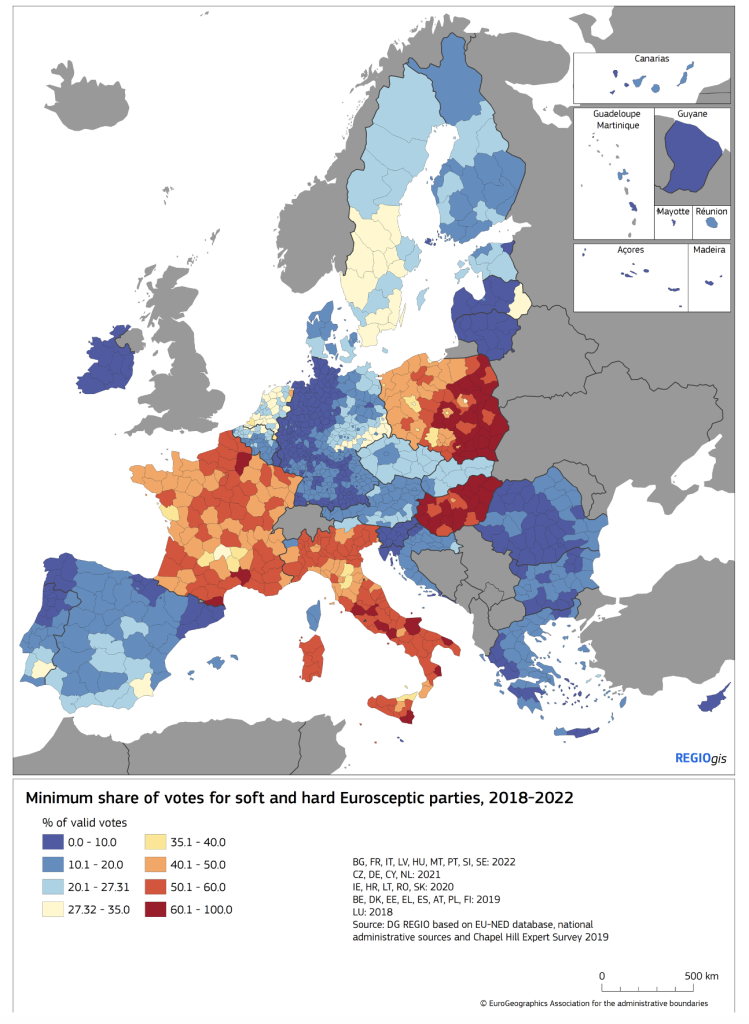

The increase in Eurosceptic sentiment has been particularly pronounced since the financial crisis and the subsequent implementation of austerity measures. It has also been in evidence in most EU member states, with the share of overall Eurosceptic vote exceeding 50% of the electorate in Hungary, Italy, Poland, and France (Figure 2). Despite Brexit possibly dampening the allure of hard Euroscepticism, the broad spectrum of Eurosceptic sentiment remains robust, suggesting a persistent and complex challenge to EU cohesion and policymaking (Stubenrauch et al. 2019, Jolly et al. 2022).

Figure 2 Votes for hard and soft Eurosceptic parties in parliamentary elections, 2018-2022

The Drivers of Discontent

The drivers of discontent in Europe are complex. As in most places where discontent has risen in recent times, they intertwine cultural, identity, economic, and demographic factors.

Cultural and identity-driven discontent stems from rapid social changes in Western societies, where increasing diversity and progressive values sometimes clash with the perceptions and adaptability of certain demographic groups. Scholars such as Hochschild (2016) highlight how these transformations can alienate those uncomfortable with new societal norms, leading to a sense of being ‘strangers in their own land’. This sentiment is particularly pronounced in rural areas and regions with older or less-educated populations, where changes in societal values and limited population mobility foster a breeding ground for Euroscepticism (Koeppen et al. 2021, Lee et al. 2018).

The economic drivers of discontent include prolonged stagnation and decline (Rodríguez-Pose 2018, McCann and Ortega-Argilés 2021). The loss of economic dynamism, coupled with demographic challenges, has left many regions across the EU particularly vulnerable to Euroscepticism. In particular, regions that have fallen into a ‘development trap’ have witnessed a rapid expansion of all forms of discontent.

The regional development trap describes areas that fail to keep pace with broader economic trends relative to other regions in their countries and to the EU and themselves in the past. Such stagnation triggers feelings of neglect and disillusionment. Frequently, the inhabitants of these regions not only feel left behind but also resent the stark and growing contrast to their more prosperous pasts and neighbours, fostering fertile ground for discontent and political disaffection (Diemer et al. 2022).

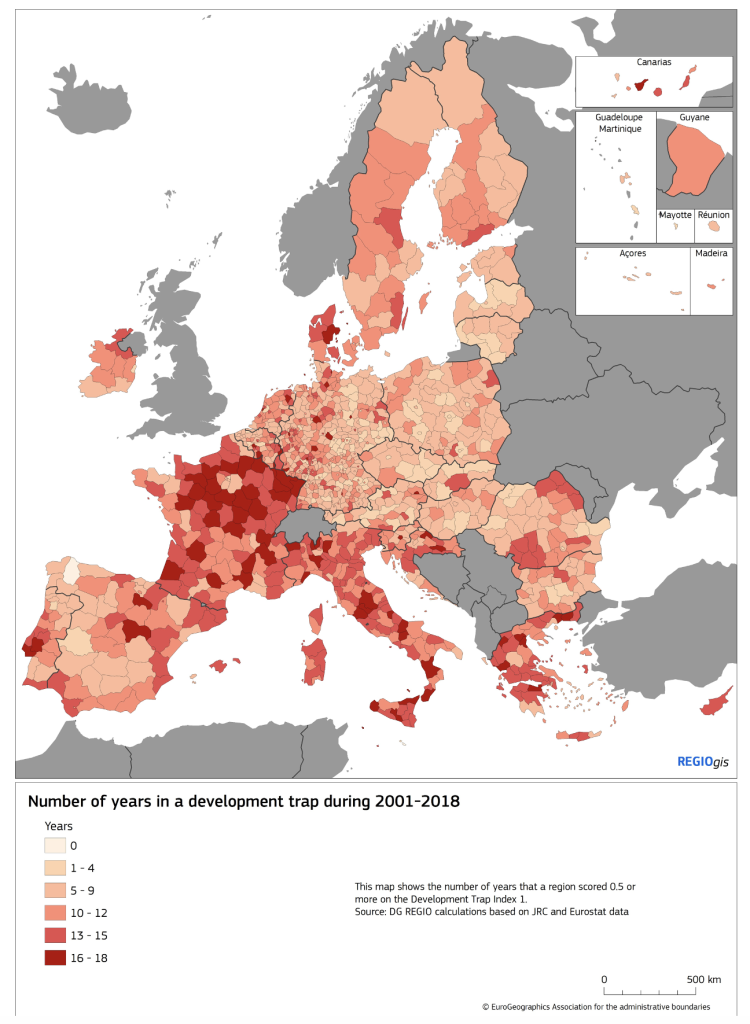

The research we conducted identifies the risk, intensity, and duration of development traps across regions of Europe since 2001. These traps are particularly pronounced in regions throughout France, Italy, and Greece, where they are widespread and enduring, inflicting profound economic scars on a population that increasingly feels neglected (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Length of the development trap (years spent in a trap), 2001-2018

The Regional Development Trap and the Geography of EU Discontent

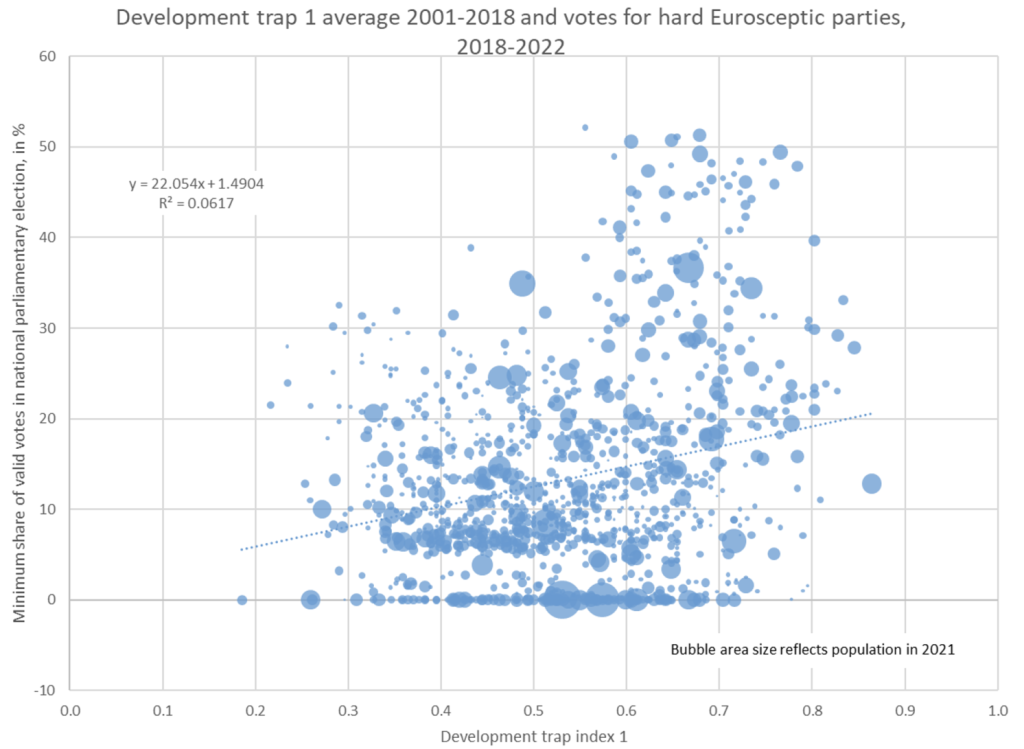

Our analysis establishes a causal link between the risk, intensity, and duration of regional development traps since the turn of the 21st century and the rise of Euroscepticism. Development trapped regions, on average, have supported hard Eurosceptic parties to a far greater extent than their non-trapped counterparts, though the relationship presents anomalies, with some high-risk areas showing negligible Eurosceptic support and vice versa (Figure 4). This positive relationship is robust to controlling for a range of regional characteristics that includes demographic factors, migration, levels of education of the population, local government quality, and other regional economic indicators. Overall, trapped regions are significantly more likely to vote for hard Eurosceptic options.

Figure 4 Correlation between the trap risk (DT1) and the hard Eurosceptic vote, 2018-2022

The analysis shows that it is not only the presence of a trap but also its depth and duration that significantly influence Eurosceptic voting patterns. Regions experiencing long-term economic decline, where the public perceives a relative decrease in their standard of living compared to other regions, show a stronger propensity to support hard Eurosceptic parties. And the longer a region remains trapped, the stronger the Eurosceptic sentiment becomes. This finding aligns with theories suggesting that perceptions of relative economic decline play a crucial role in political disaffection.

Moreover, when expanding the analysis to cover two electoral cycles, the persistence of the development trap’s impact on Eurosceptic voting is evident, emphasising that economic stagnation’s influence is not confined to a single election period. Both the risk and intensity of the development trap are crucial for understanding the geography of EU discontent, with regions that have been economically stagnant for longer periods showing considerably higher levels of Eurosceptic voting.

Conclusions

The rise in Eurosceptic voting reflects a broader political shift driven by various social, economic, and demographic factors. But over the long-term, relative local economic decline is fundamental to explain galloping discontent and Euroscepticism across the EU.

Residents of regions trapped in a cycle of low employment, poor productivity, and slow growth, compared to their past performance and that of their country and European peers, are increasingly leaning towards Euroscepticism. This trend is evident across different timeframes, showing the persistent and long-term nature of these effects. The data indicate that the longer and more intense the economic hardships, the greater the susceptibility to Euroscepticism. Discontent arises not only from current economic conditions but also from a prolonged period of comparative decline, where residents perceive a continuous erosion of their quality of life. This ongoing decline contraposes the winners and losers from structural economic changes (Stanig and Colantone 2019) and exacerbates the deterioration of public services and infrastructure, intensifying the feeling of being trapped in ‘places that do not matter’. Our analysis also suggests a directional causality from falling into a development trap to the rise of Euroscepticism, not vice versa. Persistent economic stagnation and growing regional inequality are shaping political attitudes and preferences towards European integration, thus endangering the future of the European project.

Our findings call for a significant re-evaluation of economic geography theories and the relationship between economic conditions and political orientations. They advocate for new theoretical frameworks that view political attitudes as both a result and a catalyst of economic conditions. Our study challenges conventional views that primarily attribute political discontent to cultural factors and underscores the need for policies that prevent and address development traps. These policies should include enhancing government quality, fostering innovation, and prioritising education to mitigate Eurosceptic sentiments and promote more cohesive regional development.

See original post for references

Traps are usually designed.

I’m always reminded of Prof. Michael Hudson’s quote somewhere: “The EU is a fascist project, designed to increase mortality rates and lower living standards by 20, 30 percent.” I’ll have to dig up the link somewhere

on a harddrive.

My first reaction to this was that the geographical approach is incorrect, or at least not completely correct. If one wants to locate those development traps in, for instance, Spain it i best to check the geographical distribution of votes by electoral districts obtained by VOX in recent elections. VOX is the Spanish version of the French Rassemblement National (RN) and shows Euroscepticism mostly if not uniquely related with rural policies. The Green Europe and things like that (which by the way are ill designed policies IMO even if I can agree with the supposed objectives). There are quite possibly giant pockets of development traps possibly in every European Region that cannot be identified by the administrative division in provinces.

The paper limits its scope to the identification of those pockets and some low level analysis on the underlying causes. Better job does in this sense Yves Smith in the preface and I guess one cannot expect anybody from the EU-JRC starting a rant against the general course of European PMC-directed policies. That would too much to ask for.

Anyway this was an interesting read though I suppose that there is no one in the political class in Europe able to read it and really understand what is going on.

To add something more substantial to the analysis one of the biggest mistakes that the EU is making is the belief that in all cases applies the subsidiarity principle as stated in the EU treaties. I, for instance, believe that regarding the application of rural development policies in a very diverse environment (physical, cultural, historical and economical circumstances) the issue is better dealt at state level or even at regional level rather than at EU level. The EC has outreached in its competences and we are paying for it.

I ran across mention in an article in the newspaper that half of all Italians express disapproval / disappointment with the EU. As I have mentioned, Italy has sacrificed unduly. The EU demanded dissolution of the IRI and sell-off of state-owned industries. Other casualties include the Italian labor movement and the Partito Comunista Italiano (and the left-wing socialists).

Conor Gallagher detailed the Italian economic conundrum:

https://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2023/01/italy-and-european-central-bank-are-on-collision-course-as-eu-economic-conditions-worsen.html

Italians thought (or seem to have thought) and the Italian elites seem to have schemed that giving up sovereignty to the EU would stabilize the lira (now the inflexible euro), prevent a return to fascism, and give Italy a security umbrella. The result is stagnant family incomes, the current comically greedy coalition of the “centrodestra” plus Matteo Renzi (the Hillary Clinton of Italian politics), and Carlo Calenda (kind of a Lindsay Graham but slightly less deluded), and Italy as cat’s paw for the empire’s wars in Libya and the Levant.

One might become a euroskeptic, eh.

Here is the graphic that explains the Italian distemper. Thirty years of stagnant wages, which means in effect the gradual impoverishment of the population.

https://www.openpolis.it/numeri/litalia-e-lunico-paese-europeo-in-cui-i-salari-sono-diminuiti-rispetto-al-1990/

Openpolis is, as the name suggests, an “observatory” that monitors the openness and responsiveness of the Italian government.

The Gini quotient in Italy has risen also, a signal of further wealth inequality and another indication of social tensions.

Most peripheral regions already have enough trouble getting their national governments to listen. Getting Brussels to listen as well is basically impossible unless you are some big industry lobby.

I don’t really think this study has much validity except to say that areas in long term decline are more likely to vote for radical parties, mostly of the right. I think its always an error to equate votes for specific parties as indicating public opinion on a topic – people vote according to a package of ideas and a general sense of whether a party represents their view, rarely on specific policies.

An important counterweight to the idea that an increase in the vote for those parties (which the article seems to equate with the populist right) is that while right wing Eurosceptic parties are growing, as they grow their Euroscepticism has grown weaker (paradoxically, as they focus more on specific Euro-level issues, such as the Nitrates Directive). The Ressemblement National in France and AFW in Germany have stepped back significantly over the years in advocating leaving the EU and the East European populist right are only interested in grandstanding on the issue, not actually doing anything to leave. Left wing eurosceptic parties tend to keep very quiet about this element of their policies – the Nordic Green Left and EACL groupings have noticeably stepped back in recent years from saying much about the EU apart from making vague noises about wanting more reform. There is no way these parties would be moving in this direction if they felt moving in a different one was a vote winner.

The main long term studies, by Eurobarometer and Pew, indicate no specific increase in Euroscepticism, despite votes for nominally anti-EU parties. This strongly suggests to me that the increase in vote for these parties has far more to do with issues like immigration and a general discontent with the way things are won than any specific views on the EU.

The simple reality is that if there was a genuine strong wave of anti-EU feeling in Europe, those parties would put leaving the EU front and centre of their campaigns. The fact that they don’t, indicates that this is simply not a vote winner. There is clearly a rise in anti-government and anti-establishment voices in Europe, but it is overwhelmingly aimed at national governments, not the EU.

“more likely to vote for radical parties, mostly of the right.”

Because for some reason, the left wing ones gets attacked far more viciously even when their message is largely about neighborly compassion.

I guess it demonstrates that democracy, in whatever guise, is an abnormality. And that humanity will default back to some variant of feudalism/fascism when stressed.

I think it is the issue of tribalism that rears its head up – just look at the Israeli society today, all baying for blood like Dinah’s brothers…

The labour movement and labour associated parties are mummies. Democracy (in the real, athenian sense of sortition), demands for a modicum of success, a well informed citizenry. Likely as some of the societies described in The Dawn of Everything by Graeber.

But a proper reeducation of the population at large and political equalization will never be allowed. Only some massive wars with devastating losses, famines and death waves due to climate change, or virulent pandemics could give the opening for a rebalancing of the situation. The doomscrooling that my wife acuses me comes from the fact that I am looking for the silver lining. As it happened in the past more than once.

Absolutely correct (in my opinion, of course).

I usually agree with you but here I’m going to repeat something Yves has said repeatedly and which bigwigs financing the parties you mention know all too well: for most “leave the EU countries” this means leaving the Euro which would precipitate a financial collapse of epic proportions. It cannot be done quietly or planned and the mere suggestion will precipitate banking collapse. These parties are not yet willing to “Do a biblical Samson” so causing trouble is their only realistic way to ensure support and survival. They most certainly won’t advocate exit no matter what their supporters say.

Terry Flynn: for most “leave the EU countries” … leaving the Euro would precipitate a financial collapse of epic proportions. It cannot be done quietly or planned and the mere suggestion will precipitate banking collapse.

And that vastly understates the matter, if anything. More than a banking collapse, it would mean complete destruction of the existing wealth structure and socioeconomic relations in any Eurozone state that attempted it

‘You can check in, but you can never check out.’ Never were truer words spoken!

The UK was only able to do it, obviously, because it was still on the pound, and even there elites dug in their heels and fought it bitterly for three whole years.

.

Whither then Denmark, Sweden, Poland and Hungary? Do they have more vibrant EUxit parties because they still have monetary and banking sovereignty?

Whither then Denmark, Sweden, Poland and Hungary? Do they have more vibrant EUxit parties because they still have monetary and banking sovereignty?

To be Captain Obvious, I think Marx’s line — about men making their own history, though not as they please but rather under circumstances existing already — applies to countries too, with their specific historic sociopolitical situations and outlooks.

In other words, these four countries have derived from the EU precisely what their politicians and people possessed the wit to get from it for themselves, given the extra room for maneuver that having their own currencies provided.

Specifically, Hungary under Orban’s Fidesz with its forint clearly exploits its EU membership to benefit Hungary, while exhibiting far more autonomy than Brussels likes.

Likewise, Poland with its zloty is in it for the bennies — access to the single market and as a way to punch above its weight and stick its tongue out at Russia, meanwhile defying Brussels when it feels like it.

In Sweden with its krona and Denmark with its krone, conversely, elites there have bought rather more into neoliberalism, ‘Atlanticism,’ and liberal post-religious societies — the ‘European project’ — than the East European states. Sweden and Denmark’s consequent social problems related to neoliberalism are growing, but are not yet biting as hard as they would if they were in the Eurozone and had as little room to maneuver as, say, Italy does. Thus, no EU exit parties there yet.

All I’m saying is that the countries you mention don’t have an “economic doomsday device” of the sort Michaelmas mentions constraining them. Their level of acquiescence to EU laws they dislike can more easily vary. Each one can do its own cost-benefit analysis of membership without “kaboom” being on the “leave” side. So far benefits of membership still seem net positive but things could change fast.

I think we’ll learn a lot more over the next year when the consequences of stupid political decisions begin to hit home in a larger way.

I think it extends well beyond the Euro. Of course, for those in countries old enough to remember having currencies with lots of zeros the euro is still very popular. But freedom of travel, freedom to study, and all the other rights that go with the EU are very, very popular with people from all sorts of backgrounds. This especially applies to southern countries. And they get even more popular when people realise it could be taken away, as many British have found out.

I think people who live in ‘strong’ passport and currency countries have no idea how humiliating it is for people who live in what used to be ‘weaker’ countries. This is the primary reason the EU is so popular.

Thanks. I’ll be curious, going forward, whether Czechia and Slovakia come to differ more in attitudes and what the authorities push for in each. More “apples to apples” comparison than many you could choose in the EU whilst differing in monetary sovereignty.

However I am reasonably up to date on how they have historically differed in terms of industry and other factors so know to avoid being too simplistic. Bonus I have is that I get up to date stuff from Dad’s Slovakian employee!

There is also the view that populist parties are merely hiding their true colours or biding their time in response to actively pushing for the exiting the EU.

I suspect it’s more a case of slowly slowly catchee monkey strategy.

Meloni in Italy also knows the power of the ECB.

What the government in Finland at least doing is cutting salary’s for example my friend who worked at post lost 30% his pay, he quit after that became unemployed, same with people working at hospital 30% wage cut. They have sold the electric grid to caruna. They gave 600€ million tax break to company’s. Most companies dont even hire people straight anymore its trough middleman , so if you are a person planning family its impossible in this kind of situation.They have cut hospital service, in the 90s if you call the hospital someone would answer not anymore at the same time they are subsidese private hospital with hundred of million euro. Government owned thousand of care homes but they sold them long time ago.I was doing training at hospital and heard from the nurses that the doctors take the equipment to use at their private practice, they are even using loop holes to pay less tax. Their is alot more but you get my point, if its this bad in Finland one of the best country in Europe what about the rest of eu countries. What i have notice what the rich are now doing is lobbying for higher consumer tax so they get more money from the government while we get less service

That did not actually happen. The wide strikes forced the then CEO of postal services to resign and there was a two year contract between Post and the labor union.

Well, here is my proof that it did cut 30% https://www.is.fi/taloussanomat/art-2000006222947.html. So can you show me your proof that it dint cut 30%.

You can use google to translate the article. Hope link is ok for this site

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1mDwJ

August 4, 2014

Real per capita Gross Domestic Product for Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Finland and Germany, 2000-2022

(Percent change)

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1mDwO

August 4, 2014

Real per capita Gross Domestic Product for Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Finland and Germany, 2000-2022

(Indexed to 2000)

The ECU has been rejecting the will of the voters since the last century, the voters have begun to return the favor.

My thinking is:

– Poland is a high performing economy and I would imagine it gives more than it receives in ‘European wealth transfer’ at least for an Eastern European country.

– Being in the European Monetary Union(EMU) is, and long has been, a very bad idea for Italy

– Germany likes being in the EMU because it artificially depresses their currency and thus artificially bolsters their exports/GDP. The same can be said for The Netherlands.

I would say the reason is because Poland is shipping the youth out, 2009 Poland did austerity on steroid so people moved to west Europe. This then made Poland economy look good, now when Eu do austerity they all say look at Poland austerity work.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1kUT1

August 4, 2014

Real per capita Gross Domestic Product for China, European Union, Poland and Hungary, 1992-2022

(Indexed to 1992)

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1ihMG

August 4, 2014

Real per capita Gross Domestic Product for United States, United Kingdom, Germany, France and Italy, 2000-2022

(Indexed to 2000)

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=oht2

January 15, 2018

Real Broad Effective Exchange Rate for Germany and Netherlands, 1994-2024

(Indexed to 1994)

Academic tools placed in the hands of mechanized minds may produce questionable, sometimes absurd, results. Correlation coefficients and linear regressions may produce all sorts of arguments needed to prove one’s point, whatever it may be. “Give me the gist, I’ll provide the wrapping”. The authors of the VoxEU article likely selected the variables and the data series more adept to support their conclusion, which is – don’t rock the boat, some cosmetics suffice. The sempiternal EU blabla, the same failed policies.

In the conclusion the authors “advocate for new theoretical frameworks that view political attitudes as both a result and a catalyst of economic conditions.” New, they say? The old Marx, two and a quarter century ago, posited that political attitudes, but also culture, religion, values, were the result of economic conditions. He spoke of politics as the “superstructure” of the production mode. I am not sure that economic relations determine political choices. But that would lead to a digression. As for now, I positively think that we cannot cure the European economics without previously draw a new political blueprint.

What is significant here, is that Europeans have plenty of good reasons to feel sore about the EU. They have lost economic muscle, they have lost diplomatic power, they have lost what we could name as cultural capital, they have lost their identity and they have lost their sovereignty.

“The growing dominance of the US within the Atlantic alliance is evident in virtually every area of national strength. On the crudest GDP measure, the US has dramatically outgrown the EU and the United Kingdom combined over the last 15 years. In 2008 the EU’s economy was somewhat larger than America’s: $16.2 trillion versus $14.7 trillion. By 2022, the US economy had grown to $25 trillion, whereas the EU and the UK together had only reached $19.8 trillion. America’s economy is now nearly one-third bigger. It is more than 50 per cent larger than the EU without the UK.

Of course, economic size is not everything when it comes to power. But Europe is falling behind on most other measures of power as well…American technological dominance over Europe has also grown. The large US tech companies – the ‘big five’ of Alphabet (Google), Amazon, Apple, Meta (Facebook), and Microsoft – are now close to dominating the tech landscape in Europe as they do in the US.” ( https://ecfr.eu/publication/the-art-of-vassalisation-how-russias-war-on-ukraine-has-transformed-transatlantic-relations/ )

The authors got it wrong in claiming that discontent is caused by backwardness : they assert that it is “particularly pronounced in rural areas and regions with older or less-educated populations, where changes in societal values and limited population mobility foster a breeding ground for Euroscepticism.”

EU-wariness has been fostered by the undemocratic genesis of the EU. The 2004 European Constitution was submitted to a referendum in Spain, France, the Netherlands and Luxembourg in 2005. It passed in Spain and Luxembourg, but it was vetoed in France and the Netherlands. The political elite decided there and then to put an end to other referendums, and to have a reshuffled Constitution adopted by the vassalized national parliaments. Forget the will of the people.

Another instance of undemocratic EU-building took place in 2008. The Irish people were called to vote on the 2007 Lisbon Treaty, and the result was a sound and clear no. The Irish “no” will not stop the process, asserted Zapatero in Spain, and Tusk, the chairman of the European Council, in Brussels. “The Irish will vote as many times as required until they say yes”.

Come 2015, in the middle of the Greek sovereign debt crisis, the Greek people are asked to say whether or not they accept the “troika” (EU, European Bank, IMF) financial plan. Another clear “no”, to no avail. A few weeks later, the Greek government fell, and the parliament accepted the plan.

The authors do not mention any of these episodes, because they would be hard-pressed to prove that the negative votes came from the European “deplorables”, as they suggest. Probably influenced by the social origins of the most vocal protesters against the Brussels eurocrats, the motley crowds of the Spanish Indignados, the French Nuits Debout and the Gilets Jaunes demonstrators, and the still on-going peasant protesters from France, the Netherlands, Belgium and Germany, they discard the deep meaning of the dissent by assigning it to the rural, uneducated, have-nots. A more thorough analysis would surely expose their mistake. EU-wariness is widespread among the higher-educated and often well-off strata.

The current economic reality flies in the face of the claim that “The regional development trap describes areas that fail to keep pace with broader economic trends relative to other regions in their countries and to the EU.” For whatever it is worth, GDP growth for Germany, the traditional economic engine of the European bloc, lags behind the one of such Southern countries as Greece, Spain and Portugal. The consequences of the war engaged by Europe against Russia, especially as it concerns the cost of energy, are straining the German economy to a point where it becomes difficult to guess how, to which extent, and when it will be able to recover its former health. As regards the Southern countries, their current economic good fortune rests to a large extent on the tourism services, which, further to being subject to a high volatility, are increasingly viewed by the locals concerned more as a curse than as a blessing.

Definitely, Europe is in a rut, to get out of which it has to get rid of the EU complex, and start to build from the bottom up, a new, cooperative, pragmatic, open, peer-to-peer community of nations. I feel somewhat embarrassed to say it, because the example I quote is not properly an archetype of a non-bourgeois society. Yet, couldn’t Europe become an association of independent and largely sovereign peoples, all keeping their unique culture and value-systems, engaging in mutually beneficial economic and scientific endeavors, with a subsidiary central coordinating body with limited powers, something like the Swiss federation of autonomous cantons, with different languages and cultures, and a weak federal government?

“Yet, couldn’t Europe become an association of independent and largely sovereign peoples”?

Only if Europe could successfully throw off US control, and get rid of the layers of US educated and indoctrinated compradors. That doesn’t seem likely just now.

“Only if Europe could successfully throw off US control”

So right! Regretfully, the European political and business elites have bowed, and scaled down their ambitions to just enter the contest for a well-paid job as US valets. There was a time when political leaders dreamed of winning a few pages in the history books, by embodying their people’s design to build dynamic, vigorous, prosperous and cultured societies. I guess the last representative of that breed in Europe was the French Charles de Gaulle (no personal sympathy though).

Today’s incumbents are content with nurturing a career plan, expected to take them from a junior political job, to a government position, to an international assignment : EU Commission, IMF, ECB, UN, WB, OECD, WEF, you name it. Just look at the carousel of former government officials from different European states applying and lobbying for Jens Stoltenberg’s job at NATO. There is no room left in their minds to think of the good of their constituents, to look ahead, evaluate the challenges, and to clear the way leading their fellow citizens to a brighter future.

My reading is that Europe has become a zombie society. The elites betrayed the peoples. The common man, sedated by the mainstream propaganda, is kept in a state of drowsiness required to make the daily life sufferable, trying to escape the ghosts of precariousness, debt, crumbling social net, dire outlook, widespread hopelessness. It is important to keep outbursts to the bare minimum. Awareness is rising among an increasing number of people, we could say middle-class, but we are a long way from having anything like a coherent alternative vision, and a social force mighty enough to move society forward.

The likely development is an acute crisis, caused by the fallout of the ongoing wars in Ukraine and elsewhere, with the US retreating to their courtyard (pity their neighbors!), and Europe trying to make sense of the remains of its past grandeur hereafter reduced to rags. I cannot avoid thinking of the ruin of Athens after the ill-fated expedition to Sicily. But who does read Thucydides today?

You ask “Yet, couldn’t Europe become an association of independent and largely sovereign peoples, all keeping their unique culture and value-systems, engaging in mutually beneficial economic and scientific endeavors, with a subsidiary central coordinating body with limited powers..”

Er, no is short (less sweet) answer.

The EU is a political and regulatory behemoth – it works on the principle of ‘engrenage’ – whereby, in order to keep going, it has no other option (per J C Juncker bycycle analogy of going forward) but to expand its regulatory and political ambit by taking away (and never returning) a countries competencies be it in environmental, transport, financial or myriad of other areas – this is why the EU progenitors like Arthur Salter ( yes he was a Brit, civil servant ) , Monnet and Schuman wanted (and needed) the obviation of the nation state – pesky states all had (and have their own demos) – the Kratos ( as in power) has to lie at the centre in Brussles. Democracy and the EU cannot co-exist in any conventional sense.

For all the academic or dressed up academic ‘evidence’ in the cited article it’s pretty evident that ‘populist’ parties (left or right) merely wish to redress the democratic deficit that the ordo-technocrats of Brussels (and increasingly Frankfurt) give to the member states.

Pleasingly, the UK were never quite fooled by the affable technocrats of Brussels and the Judges of Luxembourg (at the ECJ/CJEU) – as I say later, the increasing ( and silly use) of legal lawfare by the The Commission and the ECJ/CJEU was always going to lead to tears before bedtime. Worse is to come when the whole international order comes under fire via the Council of Europe institution (not of the EU but allied to it) the ECHR in Strasbourg – its judicial over-reach and integrative nature is pretty well accepted, as is agreement that it is no longer fir for purpose as per its 1951 intentions.

The music has and had to stop sometime.

“The music has and had to stop sometime”

The music will stop, surely. Europe will be short of breath, deprived of instruments, and will find itself unable to compose a tune agreeable to anybody’s ears. I cannot quite fathom the fix that Europe could design to get out of the rut, financial, industrial, demographic, cultural, in which it let itself be dragged. Granted, the EU is a big machine, a potent “engrenage”. When it crumbles, it will produce more rubble, voilà!

I was not aware of J C Juncker’s bicycle analogy of going forward. You made me think of another, a bit cynical, bicycle metaphor, this one by a former boss of mine. Organization life, he used to say, is like bicycling : while you nod upwards, you shove your feet downwards. Isn’t it what the EU “democracy” is all about : yes to the master, crush the people.

I’m always reminded of the book by Ernest Hemingway – The Sun also Rises.

Two friends Bill & Mike –

” How did you go bankrupt?” asked Bill – “Two ways”, Mike said – “Gradually and then suddenly”.

Most empires expire relatively slowly but some were quite brittle – the EU and the European Central Bank in particular, are becoming more like a ‘House of Jenga’ as time goes by – I suspect they will become victims of their own contradictory (& contra reality) values – but hey – them’s the breaks.

This kind of analysis is irritating because it tiptoes around the real issues. There are essentially two.

First, so-called “Eurosceptic” parties, which in Europe means parties attached to local communities and national sovereignty, are gaining support because they are the only political forces not totally owned by the globalisation lobby and prepared to listen to the concerns of ordinary people. It’s a fundamental insight of practical politics (though not, sadly of political science) that people vote for parties for reasons that are not necessarily related to their overt policies. Often such votes are an expression of protest against, rather than support for.

Second, the twee references to “increasing diversity and progressive values” being unpopular (we really must abolish the people and elect another) is code for the massive uncontrolled immigration into European countries over the last generation, and the consequent social problems that are not allowed to be mentioned, and the increasingly bizarre and extreme social legislation being introduced under pressure from Brussels and the ECHR. In France, for example, the political, media, entertainment and sports elites have been completely transformed, and now have a much higher percentage of immigrant groups than the general population. For many French people it’s like living in a colonised country, not least because immigrants are dumped, not in the wealthy areas where opinion formers live, but in poor areas where life is hard enough already. And yes, most of these areas are in steep economic decline, which makes it worse.

I think the authors need to get out of Brussels a bit, or at least go to one of the poorer areas, and meet real humans.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mcL5dnxXdHQ (Quo Vadis The European Union)

this u-tube with Professor Wolfgang Streek explains the problems in Europe. The EU is a failed and bungled attempt to form a superstate as a response to generations of war in the 1950’s. It never worked beyond a trading arrangement, and in the Maastrich treaty became a bulwark of neo-liberalism. Its current NATO-isation and vassalisation by the US makes it unworkable in any conceivable future. It is gradually pulling itself apart. It might be able to evolve to a federacy of sovereign nations, but is more likely to be dragged down by the collapse of American imperialism, and by the infantilisation of the European political class.

UK reader chiming in, as requested.

In the 1940s and 1950s a number of the leading theorists of common markets (such as Balassa, Meade, Myrdal, Viner, etc.) argued that common markets tend to amplify existing strengths and weaknesses. Myrdal had developed his theory of circular and cumulative causation in his celebrated, and mammoth, study of US racial discrimination (1944), and it was refined by Kaldor and Wicksell.

One of the reasons why Kaldor was so viscerally opposed to UK accession to the EC was not because of any inherent Europhobia, but because he felt that the terms of entry would lock the UK into permanent depression, with it becoming the Northern Ireland of Europe. This was because the UK had run a cheap food policy since 1846, whilst the Six ran a dear food policy. Agricultural support in the UK was financed from 1939 by deficiency payments in which the burden was borne by the taxpayer (i.e., it was progressive), whereas in the Six it was borne via the consumer through higher retail prices (i.e., it was regressive). By ditching cheap food for dear food the UK’s cost base would increase; this would make its manufactures uncompetitive in world markets, and it would be forced into stagflation.

Kaldor also argued that if a country joined a common market on the wrong foot, as the UK was bound to do by ditching cheap food, it would stay wrong-footed, specifically through the current account. Once the current account went into deficit the UK would be forced to sell assets to yield a corresponding capital account surplus. This would harm domestic investment as revenue streams would be diverted overseas. Moreover, it would have a compounding effect over time. In a common market it would not be able to apply tariffs or quotas to restore balance to current account. If it could not do that, then there would need to be a very large system of regional transfers between the member states: the MacDougall Report (1977) argued for just such a large system, but all West Germany would permit under the austerian Schmidt was something rather pallid and feeble.

As mentioned, common markets increase existing strengths, and they also encourage specialisation. Faced with the prospect of being poor and becoming poorer, the UK effectively abandoned manufacturing (as Cripps, Godley, Kaldor, Johnson, Neild, Rowthorn, etc. warned) and turned to Finance. However, that turn to Finance increased regional inequality within the UK and slowly fractured the UK’s domestic socio-economic settlement, resulting in the rise of nationalism in Scotland and Wales, and the increasing disaffection of ‘left behind’ regions within England. The result was 2016.

That outcome was all the more ironic because the very reason why the British elite turned to accession from c. 1958-59 was that the political economy of empire had disintegrated (the UK no longer had the capital to divert overseas in order to satisfy the growth aspirations of Commonwealth countries who had adopted their own import substitution policies). Therefore, the UK needed the Six as an empire substitute, which would function as a vent to UK manufactures. Read the 1969 and 1970 white papers on accession and you will see that the primary purpose of accession was something called ‘dynamic effects’ for British industry: the Six would be a large ‘home’ market for British manufactures, and competition within the EC would stimulate productivity gains within the UK (and, sotto voce, discipline labour). No evidence or modelling was provided to support the dynamic effects argument; it was faith based. By 1979 – as Godley noted – there were dynamic effects, only they were negative. The dynamic effects argument could therefore be construed as comparable to the infamous number on the side of the bus. *If* Brexit has failed, it is surely due to the nature of the 2019 demission settlement, which preserves much of the political economy of the UK’s period as a member, in which it specialised as banker to the other member states, and in which it ran a permanent deficit in manufactures (in favour of Germany) which its surplus in services was never able to overbear (there being free movement in goods but not services), resulting in the need to run ever larger capital account surpluses.

In other words, a substantive intra-EU regional transfers policy – something very much larger than that currently extant – is necessary to buy off discontent in those areas which are falling ever further behind. The critical question now is whether the surplus countries within the EU (mostly in the north) have the means or the political will to finance large enough transfers to reduce mounting antipathy to the EU project. Given the EU (like the West in general) has decided to pay higher prices for key inputs – by sanctioning Russia and alienating the Global South – it seems unlikely that this will happen. Moreover, it also seems likely to result in continuing economic stagnation and relative decline, which will only serve to increase distributional conflicts within and between member states (as also within the UK).

A fascinating and incisive analysis, Froghole. Thank you for that.

I would never publish (or allow to pass review) with a R2=0.06 and then declare a trend. Given that they hypothesize there is a trend, this tells me their classification scheme (for whatever reason) is wrong if their hypothesis is correct, this means the underlying is not supported by the data, so it is just a viewpoint piece.

Opinion pieces are important, but should be labeled as such.

Why euroskepticism is not much more spread is because of particular benefit some countries received (Germany) and most importantly gaging any political skepticism while massively funding and controlling EU national media. What we have here is wholesale bribery and massive EU propaganda hiding huge costs least of complete loss of sovereignty which in this era of collapsing US hegemony is disastrous for EU.

Here is an excerpt from Polish conservative publication “Polish Thought”.

Another UK view:

Brexit in many ways merely corrected an historic anomaly – the UK was semi detached from the EU for most of its 45 years of membership, given it’s opt outs of most of the important integrative aspects of membership – the ‘party’ couldn’t last and didn’t. Plus, it’s genuinely hard to fool most of the people all of the time, especially when over a near 50 year period, vast swathes of sovereignty were given over to the technocrats of Brussels. Tears before bedtime became the watchword.

The combination of technocratic faux democracy & legal lawfare (of the ECJ/CJEU) played badly with the UKs concept of representative demos and sense of fair play – the EU/napoleonic codex always jarred with UK common law too. Plus the ever increasing caucusing of the eurozone finally did for many in the UK once it was understood how QMV supported & favoured the eurozone members over non members.

What’s happening in the EU today is partly a result of COVID – in which, despite the hype, the EU didn’t exactly cover itself with glory or competence. The Ukraine war has tragically exposed fractures in the EU polity that even the Commission can no longer hide.

But the real, larger tragedy is the Euro monetary system (EMS) known mainly by its physical manifestation and abject failure of ‘the euro’ to cause convergence in Eurozone member states. Most informed people know and reluctantly accept the inherent design failures in the Euro – unfortunately, the politicians at the time, were too keen to shoehorn a political and overly regulatory project without the economic foundations necessary to do so.

One doesn’t need to be a Professor or Reader in economics to understand the bizarre consequences of the EMS and its Target 2 measures on different economies (or regions) ( if you like) when the debt/surplus transfer mechanisms just don’t exist to enable stable economic or fiscal policies.

Add the legal lawfare by the ECB/ECJ and undoubted democratic deficit of the Commission into the equation – what could possibly go wrong?

The comments here comprehensively outshine the tepid effort of the authors themselves — I continue to be impressed with the breadth and depth of critical thought of the commentariat.

William Mitchell warned about the inevitable contradictions of the neoliberal trap which is the EU in Eurozone Dystopia: Groupthink and Denial on a Grand Scale and subsequently offered some way forward with Fazi in their Reclaiming the State