Lambert here: Wait a minute. Cartels… “consumer welfare”… Reminds me of something, can’t quite put my finger on it….

By Marit Hinnosaar, Assistant Professor University Of Nottingham, and Toomas Hinnosaar, University of Nottingham Economic Theory Centre. Originally published at VoxEU.

Social media influencers account for a growing share of marketing budgets worldwide. This column examines a problem within this rapidly expanding advertising market – influencer cartels, in which groups of influencers collude to increase advertising revenue by inflating each other’s engagement numbers. Influencer cartels can improve consumer welfare if they expand social media engagement to the target audience, but reduce welfare if they divert engagement to less relevant audiences. Rewarding engagement quantity encourages harmful collusion. Instead, the authors suggest, influencers should be compensated based on the actual value they provide.

Imagine a university that rewards professors based on the number of citations to their research. In response, a group of colleagues might agree to cite each other’s work in every paper they write. What would be the positive and negative effects of our imaginary citation cartel? Economists are not known for excessive citations, which could be explained by positive externalities: the citing author bears all the costs, while the cited author reaps the benefits. As citing authors can’t internalise this positive externality, we end up with fewer citations than is socially optimal.

A citation cartel could solve this issue via reciprocal behaviour: by the cartel agreement, members would receive as many citations as they give. However, this can go too far. If this agreement requires citing unrelated papers, it might be good for group members but lead to meaningless literature reviews. Thus, the benefit of such agreements depends on their nature: making more effort to cite related papers could be good, while citing unrelated papers is probably bad.

Such academic citation cartels are not purely hypothetical. Academic journals have been found to form agreements to boost each other’s journals in the rankings (Van Noorden 2013). Similarly, universities have boosted their colleagues’ citation counts to advance in university rankings (Catanzaro 2024). Due to such citation patterns, Clarivate (Thomson Reuters) has excluded journals from Impact Factor listings, and most recently excluded the entire field of mathematics (Van Noorden 2013, Catanzaro 2024).

Academic citation cartels are difficult to study because there is no data on explicit cartel agreements. But in influencer marketing, cartel agreements are observable. In our new paper (Hinnosaar and Hinnosaar 2024), we study how influencers collude to inflate engagement and the conditions under which influencer cartels can be welfare-improving.

Distorted Incentives and Fraudulent Behaviour in Influencer Marketing

Influencer marketing has become a key part of modern advertising. In 2023, spending on influencer marketing reached $31 billion, already rivalling the entirety of print newspaper advertising. Influencer marketing allows advertisers fine targeting based on consumer interests by choosing a good product-influencer-consumer match.

Many non-celebrity influencers are not paid based on the success of their marketing campaigns. In fact, less than 20% of companies track the sales induced by their influencer marketing campaigns. Instead, influencers’ pay is based on impact measures such as the number of followers and engagement (likes and comments), furnishing an incentive for fraudulent behaviour – for inflating their influence. Inflating influence is a form of advertising fraud that causes market inefficiencies by directing ads to the wrong audience. An estimated 15% of influencer marketing spending is misused due to exaggerated influence. To address this issue, the US Federal Trade Commission proposed a rule in 2023 to ban the sale and purchase of false indicators of social media influence. Cartels provide a way of obtaining fake engagement that does not fall directly under the proposed rule – because no money changes hands – but is still in the same spirit. While there is substantial literature on fake consumer reviews (Mayzlin et al. 2014, Luca and Zervas 2016) and other forms of advertising fraud (Zinman and Zitzewitz 2016), the literature on influencer marketing has focused mostly on advertising disclosure (Ershov and Mitchell 2023, Pei and Mayzlin 2022, Mitchell 2021, Fainmesser and Galeotti 2021), leaving the fraudulent behaviour unstudied.

How Do Instagram Cartels Work?

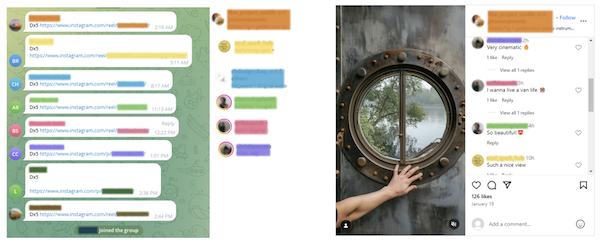

An influencer cartel is a group of influencers who collude to boost their advertising fees by inflating engagement metrics. As in traditional industries (Steen et al. 2013), influencer cartels involve a formal agreement to manipulate the market for the members’ benefit. The cartels operate in online chatrooms. The screenshots below show how one such cartel operates in practice. The image on the left is from an online chat room, where cartel members submit links to their content for extra engagement. Before submitting a link, they must reciprocate by liking and commenting on other members’ posts. An algorithm enforces these rules. The image on the right shows these cartel-induced comments on Instagram. The cartel history and rules make it possible to observe which engagement (comments) originate from the cartel.

Figure 1 Left panel shows posts in online chatroom submitted for cartel engagement; right panel shows Instagram comments originating from the cartel

Source: Left panel is a screenshot of a Telegram group; right panel is a screenshot from Instagram. To preserve anonymity, account identifiers are blurred and the photo is replaced with an analogous photo by an AI image generator.

What Distinguishes ‘Bad’ from ‘Not-So-Bad’ Cartels?

Our theoretical model formalises the main trade-offs in this setting, in the spirit of the imaginary citation group discussed earlier. The model focuses on strategic engagement, a decision that affects social media content distribution and consumption (Aridor et al. 2024) but has been underexplored (with the exception of Filippas et al. 2023, who studied attention bartering in Twitter). Engaging with other influencers’ content has a positive externality, leading to too little engagement in equilibrium. Forming a cartel to reciprocally engage with each other’s content can internalise this externality and might be socially desirable. However, it can also result in low-value engagement, especially when advertisers pay based on quantity rather than quality.

The key dimension to differentiating ‘bad’ from ‘not-so-bad’ cartels is the quality of cartel engagement. By ‘high quality’, we mean engagement coming from influencers with similar interests. The idea is that influencers provide value to advertisers by promoting a product among the target audience: people with similar interests, such as vegan burgers to vegans. If a cartel generates engagement from influencers with other interests (meat lovers), this hurts consumers and advertisers. It hurts consumers because the platform will show them irrelevant content, and advertisers are hurt because their ads are shown to the wrong audience. Whether or not a particular cartel is welfare-reducing or welfare-improving is an empirical question.

Evaluating engagement quality using machine-learning methods

To answer this empirical question, we use novel data from influencer cartels and machine learning to analyse Instagram text and photos. The cartel data allows us to directly observe which Instagram posts are included in the cartel and which engagement originates from the cartel (via cartel rules). Our dataset includes two types of cartels, differentiated by cartel entry rules: topic cartels (which only accept influencers posting on specific topics) and general cartels (with unrestricted topics).

Our goal is to compare the quality of natural engagement to that originating from the cartel. We measure the quality by the topic match between the cartel member and the Instagram user who engages. To quantify the similarity of Instagram users, we generate numeric vectors (embeddings) from the text and photos in Instagram posts using a large language model (Language-agnostic BERT Sentence Embedding) and an analogous large neural network (Contrastive Language Image Pre-training model). Then we calculate cosine similarity between the Instagram users based on these numeric vectors.

Are the Cartels Likely to Be Welfare-Improving?

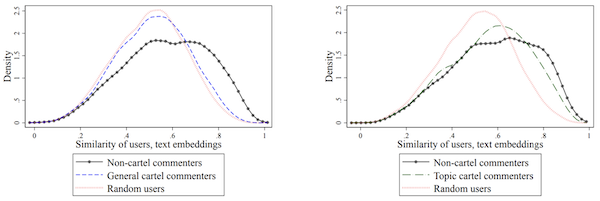

We find that engagement from general cartels is significantly lower in quality compared to natural engagement. Specifically, the quality of engagement from these cartels is nearly as low as that from a counterfactual engagement from a random Instagram user. In contrast, engagement from topic cartels is much closer to the quality of natural engagement.

The figure below illustrates these effects using raw data (see the paper for regression estimates, robustness checks, and additional analysis). It presents distributions of cosine similarity between the author and commenter, separately for general (left panel) and topic (right panel) cartels. It shows that non-cartel commenters (natural engagement) have the highest similarity with the author of the content, and random users have the lowest. Match quality from general cartels is similar to random engagement (left panel). In contrast, topic cartel engagement is much closer to natural engagement (right panel).

Figure 2 Probability density of authors’ similarity to commenters and random users in general cartels (left) and topic cartels (right)

Back-of-the-envelope calculations (based on regression analysis) show that if advertisers pay for cartel engagement as if it were natural engagement, they receive only 3–18% of the value with general cartels, and 60–85% with topic cartels. In other words, general cartels provide nearly worthless engagement for advertisers, while topic cartels cause less distortion.

Conclusions and Policy Implications

Our findings lead to three policy implications. First, since general cartels are likely to reduce welfare, stronger regulation of their activities would benefit society. Second, regulations that prohibit buying and selling fake social media indicators should also cover in-kind transfers, such as paying for engagement with reciprocal engagement. Third, the current practice of rewarding engagement quantity encourages harmful collusion. A better approach would be to compensate influencers based on the actual value they provide. Luckily, many advertisers are already moving in this direction. Until they get there, platforms could improve outcomes by reporting match-quality-weighted engagement.

“A better approach would be to compensate influencers based on the actual value they provide.”

We already have that. It’s called a Darwin Award.

“A better approach would be to compensate influencers based on the actual value they provide. Luckily, many advertisers are already moving in this direction.”

Luckily??? Only an economist could write such dribble. The question that should be asked is whether advertisers add any “actual value” to society since they are the real ‘influencers.’ As best I can tell, advertising costs just get tacked on to consumer costs in an arms race for customers — so we end up paying more for useless profit shuffling. And all the while advertisers are programming people to buy crap they don’t really need, which generates massive waste that ends up at the dump, while making climate chaos worse, and annoying all of us with commercial jingles and distracting images along the way. Maybe the solution is to regulate advertising — as in doing away with it entirely. And then people might go back to buying only what they need, to reading books instead of watching a computer screen, and to talking to each other rather than reading some numbskull’s twitter feed. And perhaps along the way we can go back to actual journalism, rather than a corporate-funded mass media designed to manufacture consent. News funded via advertising has been a disaster. It continues to create a bunch of mindless consumers incapable of critical thinking — which is why we end up with choices like Trump and Biden. The old saying – ‘you get what you pay for’ — has never been more true. Free infotainment is about controlling our world views for corporate profit — to maintain a system of mafia-monopoly capitalism.

“A world built on fantasy. Synthetic emotions in the form of pills. Psychological warfare in the form of advertising. Mind-altering chemicals in the form of… food! Brainwashing seminars in the form of media. Controlled isolated bubbles in the form of social networks. Real? You want to talk about reality? We haven’t lived in anything remotely close to it since the turn of the century. We turned it off, took out the batteries, snacked on a bag of GMOs while we tossed the remnants in the ever-expanding Dumpster of the human condition. We live in branded houses trademarked by corporations built on bipolar numbers jumping up and down on digital displays, hypnotizing us into the biggest slumber mankind has ever seen. You have to dig pretty deep, kiddo, before you can find anything real. We live in a kingdom of bullshit. A kingdom you’ve lived in for far too long. So don’t tell me about not being real. I’m no less real than the f**king beef patty in your Big Mac.” Mr. Robot

This behavior was identified even in the 2010s, before the rise of the term & formalized position of “influencer”, for its detrimental effects within nominally leftist & social justice-oriented digital spaces.

https://scribe.rip/what-is-social-capitalism-c7e01007d058 (quoted below)

Second screenshot of 2 tweets from one Twitter user reads: “From what I know a number of big accounts use DM groups to excommunicate accounts they find annoying by collectively muting since blocking affects patreon substriptions… I heard they keep a ledger with sensitive info on them to blackmail them later to market their merch or they’ll expose them at work for listening to problematic content”

Referenced also is a BuzzFeed article on the generalized practice.

https://www.buzzfeed.com/juliareinstein/exclusive-networks-of-teens-are-making-thousands-of-dollars?bftwnews&utm_term=4ldqpgc#4ldqpgc (quoted below)

Teens and twentysomethings with large Twitter followings are making thousands each month by selling retweets, multiple users who engage in the practice told BuzzFeed News.

The practice is known as “tweetdecking,” so named because those involved form secret Tweetdeck groups, which they call “decks.” Scoring an invite to join a deck usually requires a follower count in the tens of thousands.

Within these decks, a highly organized system of mass-retweeting exists in order to launch deck members’ tweets — and paying customers’ tweets — into meticulously manufactured virality.

Customers, which can include both individuals and brands, pay deck owners to retweet one or more of their tweets a specified number of times across deck member accounts. Some decks even allow customers temporary access to the deck, almost like a short-term subscription to unlimited deck retweets. Single retweets tend to cost around $5 or $10. Week- or monthlong subscriptions can cost several hundreds of dollars, depending on the deck’s popularity.

People who run their own decks frequently make several thousands of dollars each month, multiple deck owners said.

I think Gamergate uncovered something similar, where gaming journalists ran a mailing list where they coordinated their views on various games to give a unified “message”.

This “cartel” sounds like a lot or work. I was under the impression these influencers just purchased fake followers by the thousands to boost their appeal to advertisers.

The whole social media/influencer/advertising thing is just a huge heap of white hot stupid to begin with and the fact that time and effort is put into it and and lots of money exchanges hands because of it is further confirmation that humanity is probably not going to make it.

Eagerly awaiting the new, improved A.I. Influencer Tool, available to a select few, human or not.

Imagine the possibilities, where one merely inputs a theme and a desired result. Extra fees for broader reach

, throw weight, impact crater. /sI stumble on some of these influencers from time to time in my meanderings on YouTube but typically cannot say that I am impressed. So how do they get all those followers? I saw how Biden invited a whole bunch of them to the White House not that long ago but did not recognize any of the names. Maybe it is a generational thing or something. I don’t know. But be sure to go to my YouTube channel to find out and be sure to like and subscribe! /sarc

So, an experience related to this “cartel” (or fake engagement) behavior: I tried uploading a video clip to one of those Youtube channels that shows a bunch of video clips – a very big channel with over 18 million subscribers. To upload the video I was sent to a licensing agency (which does make sense – there is no way some of these clip channels can gather all the videos themselves. It also explains one reason for seeing the same clip in different places) but what was interesting about the licensing agency is that it was also a talent agency to represent Youtube personalities and they offered more than just access to licensed videos – no, they gave you access to all the other Youtube channels they represented as they would (for you) cross post between all their channels to support their group of creators they had under contract. I believe at the time they claimed to represent over 1800 influencers/creators over various platforms (Yeah, it’s not just Instagram to Instagram or Youtube to Youtube – it’s cross platform). You could submit a demo real to them to see if they would represent you – but they also accepted straight up auditions if you don’t have your own subject or thing established – just sit down and read off a piece of paper and if you do so articulately and with style and they liked you they could find you a subject or channel theme and they provide the backdrop, set, props, script, (and I suspect wardrobe in a couple of cases) …. which makes me think of reports where a quarter to a third of college students, undergrad and graduate, say their goal with the degree is to become an influencer – especially scary with journalism. This got me into a little rabbit hole but I can’t look at comments now without seeing obvious cross-commenting and the “astroturfing” that has always been a large part of Youtube but is only increasing.

As for the video clip, I didn’t upload it because of the terms. One eyebrow of suspicion went up when the webpage said something like “you might even make some money from it!” without disclosing even the broadest details of the agreement BEFORE submitting the form and video and was not included in the terms . I wasn’t looking for money but that rubbed me the wrong way – but not as much as the rights: You signed away all rights to the video except for *personal* use on social media and even the way this was worded sounded like that social media would be limited to your *personal* Facebook and Twitter accounts. So not only is somebody going to give you something for free that you will make money off of, you are going to limit that person’s usage of what they gave you for free? I passed.

The key problem is the engagement on the platform being the metric instead of the actual sales of the product. It’s like those IPOs that have never made a profit. Since the dot.com boom, reason has gone out the window.

“When a measure become a target, it stops being a good measure.”

Some variant of that has been stated time and time again across the social sciences.

I don’t understand why there is such a thing as “influencer marketing”. If you understood that influencers are not recommending something because they like it, but because advertisers are paying them, would you be inclined to buy?

Yes, a lot of people work that way. They really believe the influencer at least likes the product, their influencer imaginary friend would not deceive them!

My wife displays this behavior sometimes. She says “Oh this is recommended by X, but she also recommends less expensive items as well as top $$$ stuff, so she must be genuine.”

Well, to a first approximation it takes just as little effort to recommend product A at $100 as $B at $10. With LLM fakery, the difference in effort is almost certainly now epsilon.

An Asterix story came to mind:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Asterix_and_the_Soothsayer

This is a well known influence tactic. If you recommend something less expensive as well as the more expensive product, you are perceived as more sincere. In these cases the sales of the more expensive actually improve due to the perception of sincerity. Excellent book on this by Robert Cialdini “Influence, the Psychology of Persuasion”. It also has some possible explanations for general influencer effect. It can be due to Social Proof as you following what well known personalities are recommending or to Liking in which the like you have for the influencer has an outsize impact on your decisions.

Easy solution. We Always Ignore ALL advertisements and move on with Life.