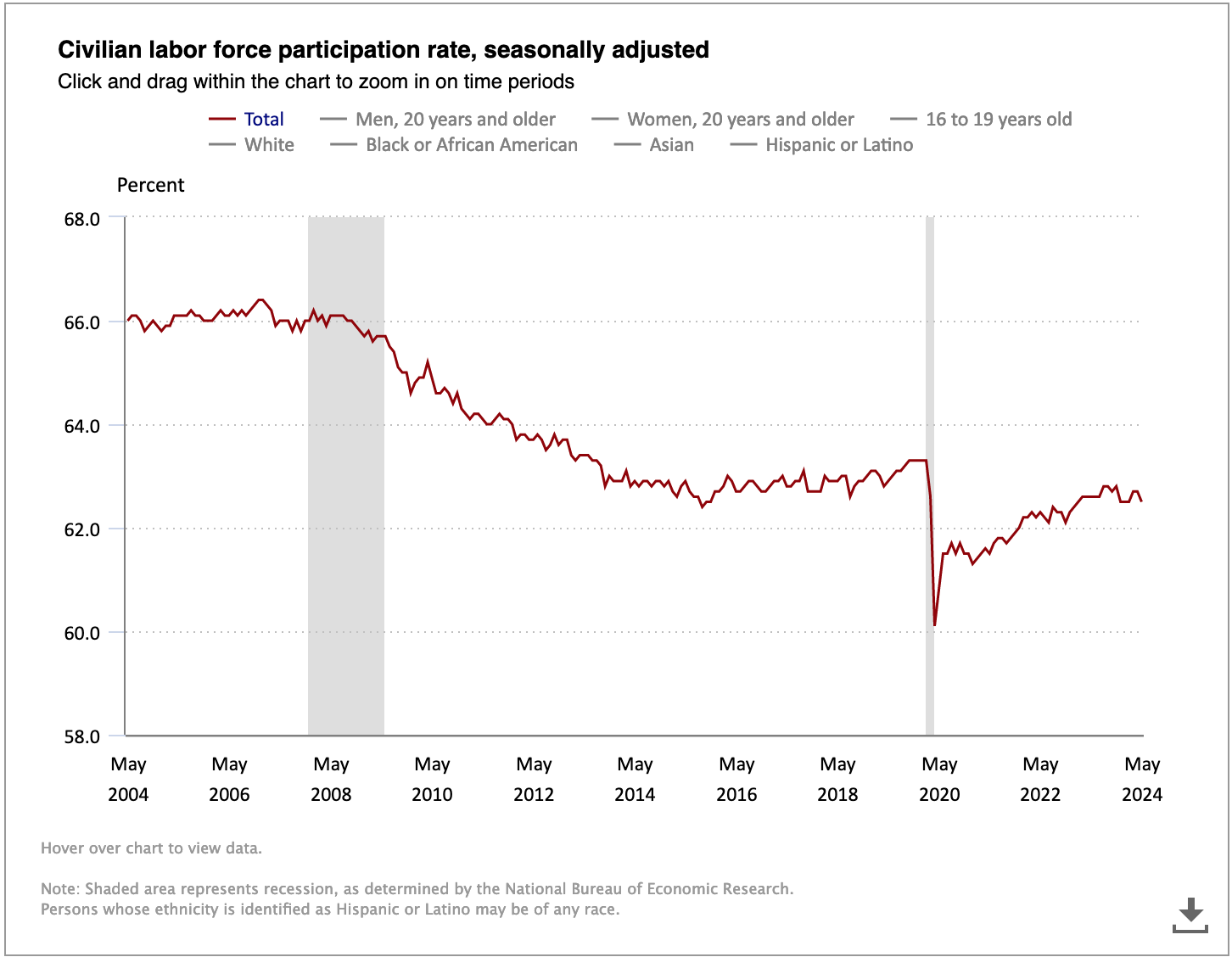

Yves here. It is striking to see how long it has taken for economists to take a serious look at how retirements, particularly earlier-than-otherwise-might-have-happened retirements have helped produce tight labor markets and thus contributed to inflation. The long-term trend is apparent below. Labor force participation never recovered during the post-financial-crisis era to earlier levels; that was why economists and policy-makers regularly wrung their hands about secular stagnation. And after the Covid downdraft, even with massive federal deficits providing a tailwind, labor force participation has not returned to pre-Covid rates:

Note that the detailed breakdown at the Bureau of Labor Statistics site shows that the age range in the table above is 16 to “75 and older”, so it does include the recent trend of some older people working beyond retirement age.

IM Doc has provided ample anecdata of very high levels of early doctor and nurse retirements, not just in his hospital, but reported by his many former students in their health care systems. Doctors are admittedly a special case because the practice of medicine has become much less psychologically rewarding, due to the rise of intrusive oversight, non-care-enhancing administrativa, Covid stresses, and now staff shortages producing a further down spiral (doctors having to take up the case load of retiring colleagues).

Another factor that this post does not explore is the runup in house prices (at least in bigger homes with work-at-home potential) in the wake of Covid. Did some wannabe retirees cash out, or alternatively take more comfort in the (hopefully sustained) improvement in their net worth?

Similarly, the authors have not considered whether Covid directly contributed to accelerated retirement via health costs such as Long Covid, or alternatively (as happened with both health care workers and pilots), refusal to take the vaccines led to firings or resignations in meaningful numbers. So there is more analytical work to do on this topic!

By Guido Ascari, Economic Advisor and Head of Monetary Policy Research De Nederlandsche Bank; Professor of Economics, Department of Economics and Management University Of Pavia; Jakob Grazzini, Associate Professor University Of Pavia; and Domenico Massaro, Associate Professor University Of Milan. Originally published at VoxEU

The Covid-19 lockdowns and other anti-pandemic measures triggered a surge in layoffs and discharges. This column investigates the impact of these layoffs on the post-pandemic surge in inflation. Workers unemployed due to a layoff are more likely to retire than employed workers. Pandemic-induced layoffs led to early retirements, which decreased labour supply, increased labour market tightness, and caused inflationary pressures by driving up wages. While the pandemic shock had only transitory effects on output dynamics, it caused a persistent decrease in the labour force due to an unprecedented increase in retirees.

Inflation surged unexpectedly after the Covid-19 pandemic, prompting significant discussion among scholars and policymakers about its causes. In the context of the US economy, recent studies have identified several key factors driving inflation. These include a sharp rise in demand for goods over services (Blanchard and Bernanke 2023, Ferrante et al. 2023), domestic and international supply chain disruptions (Amiti et al. 2023, di Giovanni et al. 2023, Ascari et al. 2024a), substantial fiscal measures combined with accommodative monetary policy boosting demand in a constrained supply environment (Bianchi et al. 2023, Jorda and Nechio 2023, Comin et al. 2023), rising energy prices (Gagliardone and Gertler 2023 Leigh et al. 2022), and a tight labour market (Koch and Nourelding 2023, Benigno and Eggertsson 2023).

In a recent paper (Ascari et al. 2024b), we explore how the temporary layoffs at the onset of the pandemic contributed to inflation outcomes via their large and persistent impact on retirement behaviour and on the labour force. More specifically, we show that pandemic-induced layoffs led to early retirements – a phenomenon known as the ‘Great Retirement’ (Montes et al. 2022) – which decreased labour supply, increased labour market tightness, and caused inflationary pressures by driving up wages.

The Impact of the Great Layoff: Empirical Evidence

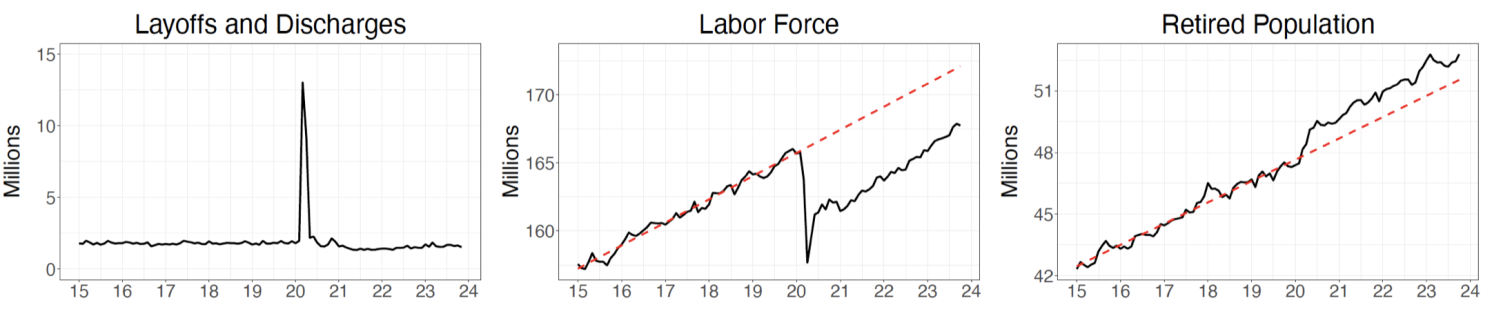

During March and April 2020, lockdowns and anti-pandemic measures triggered the Great Layoff, an unprecedented surge in layoffs and discharges, with about 22 million workers separated from their jobs in only two months (Figure 1, left panel). Concurrently, the labour force dropped dramatically, with about 8 million individuals exiting the workforce (Figure 1, middle panel). Importantly, this labour force drop has been very persistent and has only partially recovered. Additionally, the number of retirees increased by 2 million in a few months (from February to July 2020), opening a persistent gap in levels with respect to the pre-pandemic trend of roughly 1.2 million people that has not been reabsorbed (Figure 1, right panel).

Figure 1 Unprecedented surge in layoffs, persistent drop in the labour force, increase in retirements

Note: Left: Layoffs and discharges in millions (data: FRB San Francisco, based on JOLTS, BLS). Middle: Solid black line is the labour force (age 16+) in millions; dashed red line is a linear trend estimated from 2015:M1 to 2020:M2 (data: CPS-IPUMS, BLS). Right: Solid black line is the retired percentage of the population (age 16+); dashed red line is a linear trend estimated from 2015:M1 to 2020:M2 (data: CPS-IPUMS, BLS).

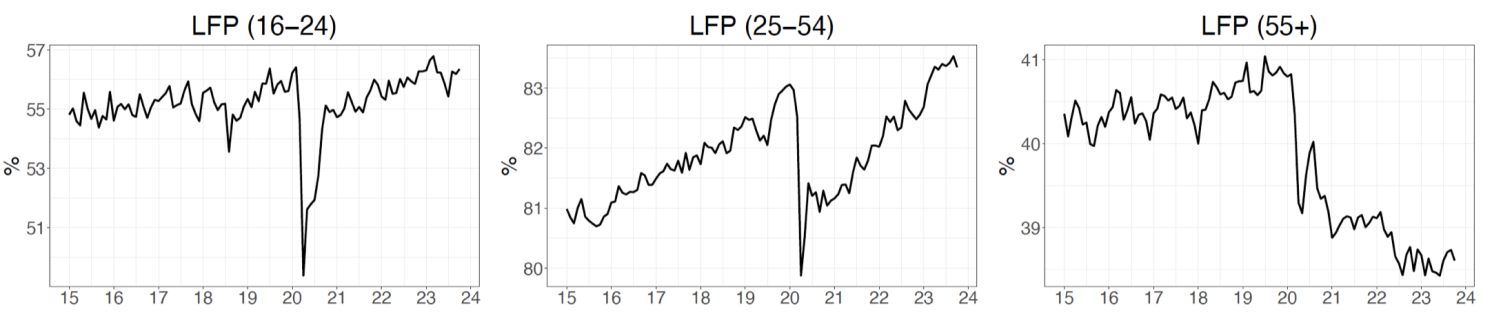

Figure 2 displays labour force participation (LFP) by age group. Following the sudden drop in the first months of the Covid-19 pandemic, LFP recovered for individuals in both the 16–24 and the 25–54 age groups. The former recovered after a few months while the latter displayed much more persistent effects from the initial shock. On the other hand, LFP for individuals aged 55 or older showed an overall downward trend.

Figure 2 Labour force participation by age group

Note: Left: Age group 16–24. Middle: Age group 25–55. Right: Age group 55+ (data: CPS-IPUMS, BLS).

Motivated by the evidence above, in what follows we discuss: 1) the relationship between layoffs, retirement behaviour, and inflationary pressures in the form of higher wages, and 2) the impact of the Great Retirement on recent inflation.

From the Great Layoff to Inflationary Pressures

Our empirical analysis articulates in two main points. First, using data from the Current Population Survey (CPS), a monthly survey of about 60,000 US households conducted by the US Census Bureau for the Bureau of Labor Statistics, we evaluate the relationship between layoff and retirement behaviour. 1 Our results suggest that workers who are unemployed due to a layoff are, in general, significantly more likely to retire than employed workers. Furthermore, the effect of a layoff on retirement decisions is significantly greater for older workers. As suggested in the literature, older displaced workers face more difficulties in securing new employment due to the loss of firm-specific skills, employers’ reluctance to invest in workers near the end of their careers, high job-search costs, and other reemployment barriers such as age discrimination (Chan and Stevens 2004, Coile and Levine 2011). Our empirical findings indicate that the link between layoffs and retirement decisions is not unique to the pandemic crisis. The peculiarity of the Covid-19 shock lies in its unprecedented size: a Great Layoff is at the origin of the Great Retirement.

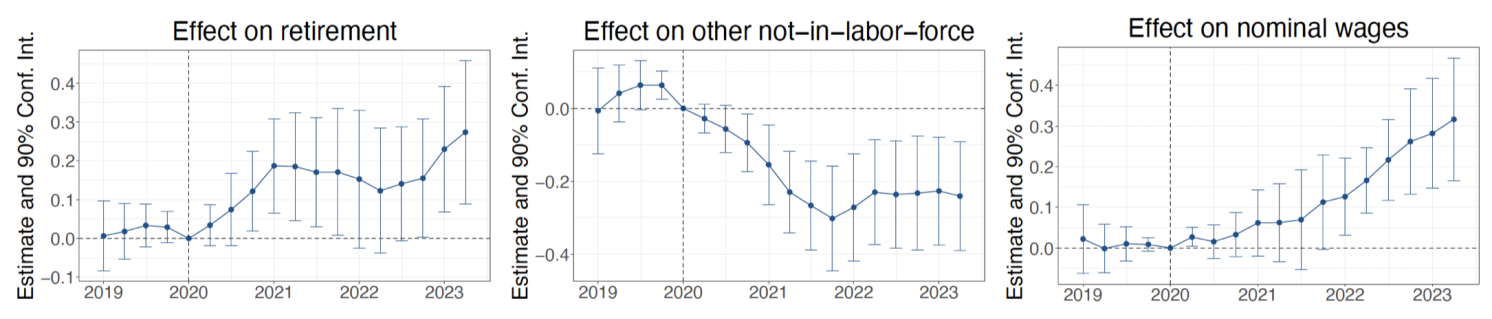

Second, we study whether the mechanism relating layoffs to retirement decisions generated inflationary pressure via higher wage growth. To this end, we estimate dynamic responses of retirement and wages to exogenous shifts of labour demand using a county-level exposure research design that leverages the Great Layoff natural experiment. Our measure of county exposure to the common labour demand shock that occurred in March and April 2020 is the average change in employment across industries, weighted by industry shares in each county’s employment before the Covid shock. Estimated multipliers use data from the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW) by the Bureau of Labor Statistics and are reported in Figure 3.

Figure 3 Counties more exposed to the Great Layoff display more retirements and higher wages

Note: Left: Dynamic response of retirement to the Great Layoff (data: CPS-IPUMS, BLS and QCEW, BLS). Middle: Dynamic response of individuals not in labour force and not retired to the Great Layoff (data: CPS-IPUMS, BLS and QCEW, BLS). Right: Dynamic response of nominal wages to the Great Layoff (data: QCEW, BLS).

The estimated response of retirement (Figure 3, left panel) confirms that the Great Layoff led to early retirements among older displaced workers. We thus observe a stronger increase in retirement in counties most exposed to contact-intensive industries. The response of the share of individuals who are not in the labour force but not retired (Figure 3, middle panel) is consistent with the evidence presented in Figure 2: counties more exposed to the Great Layoff because of their industrial composition display a stronger reduction of individuals not in the labour force and not retired – that is, younger workers flowing into the labour force. The response of nominal wages (Figure 3, right panel) documents the inflationary effect of the Great Layoff: counties more exposed to the temporary negative labour demand shock experience a larger increase in nominal wages.

The positive response of wages to a negative labour demand shock is consistent with the fact that the latter caused a persistent shift in the labour supply due to the Great Retirement. Eventually, re-entry of displaced younger workers in the labour force – together with the entry of new workers who were outside the labour force (Figure 3, middle panel) – are making up for the gap. But the process takes time, as suggested by Figures 1 and 2, such that a transitory labour demand shock determined persistent negative effects on labour supply.

Quantifying the Impact of the Great Retirement on Inflation

Given the lack of inflation data at the county level, we use a model to assess the quantitative effect of the Great Retirement on aggregate inflation. More precisely, we develop a New Keynesian model with two agent types, young and old, matching frictions and endogenous labour force participation. In our framework, the retirement trajectory influences inflation because an increase in retirements reduces labour force participation, thereby increasing labour market tightness. A tighter labour market decreases the vacancy filling rate, raising the value of a filled vacancy. This effect, combined with the increased outside option value for households deciding on labour market participation, exerts upward pressure on wages. This mechanism raises marginal costs for producers, leading to higher inflation.

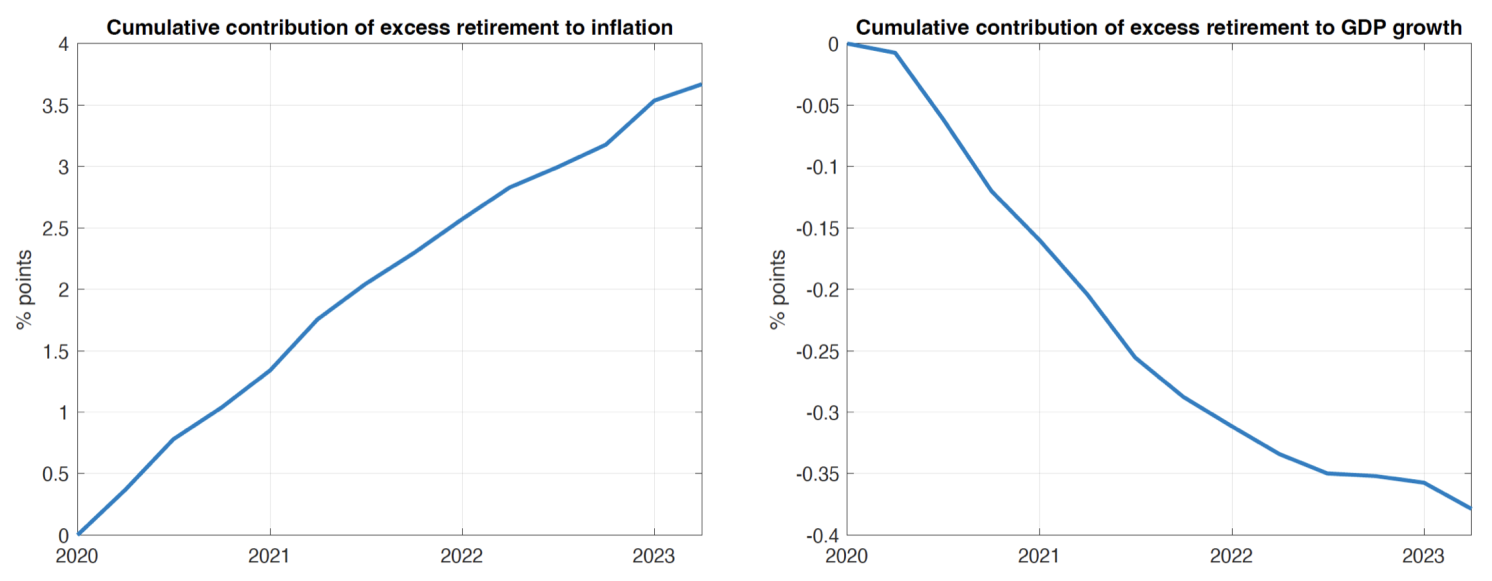

To quantify the role that the Great Retirement has played in the post-pandemic inflation dynamics, we first estimate the model with pre-Covid US data on real GDP growth, CPI inflation, policy rates, changes in labour force participation and retirement rate, real wage growth, and consumption growth. We then compare our baseline model with a counterfactual economy in which the Great Retirement never happened to isolate its impact on aggregate variables. 2Figure 4 reports the contribution of the Great Retirement on inflation and output by showing the cumulative percentage difference between the baseline and the counterfactual economy from 2020:Q1 to 2023:Q2.

Figure 4 Cumulative contribution of the Great Retirement to inflation and to output growth

Note: Left: Cumulative contribution to inflation. Right: Cumulative contribution to real GDP growth.

According to the counterfactual exercise, the Great Retirement had a positive impact on inflation equal to roughly 3.7 percentage (cumulative) points of inflation from 2020:Q1 up to 2023:Q2, divided roughly by 1% in 2020, 1.3% in 2021, 0.9% in 2022, and the rest in the first quarters of 2023. Moreover, it had a negative impact on output equal to roughly 0.38 percentage (cumulative) points of GDP growth from 2020:Q1 to 2023:Q2, divided roughly in 0.12% in 2020, 0.17% in 2021, 0.06% in 2022, and the rest in the first quarters of 2023.

Concluding Remarks

Labour market tightness has been identified as an important determinant of post-pandemic inflation. Our study focuses on a specific channel through which labour market dynamics could have affected inflation by investigating the role of retirement decisions and labour force participation. We show that while the pandemic shock had transitory effects on output dynamics, it caused a persistent decrease in the labour force due to an unprecedented increase in retirees. The persistent reduction in the labour supply to the Great Layoff had a significant impact on inflation, equal to roughly 3.7 percentage cumulative points from 2020:Q1 to 2023:Q2.

See original post for references

I read this carefully but never found the words “life expectancy”. I would be very surprised to learn that the drop in life expectancy (which is still dropping, last time I checked!) wasn’t a contributing factor to both labor force participation and people’s considerations in early retirement.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1pD6q

January 15, 2018

Life Expectancy at Birth for United States, United Kingdom and Ireland, 2017-2022

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1p7yP

January 15, 2018

Life Expectancy at Birth for United States, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan and United Kingdom, 2017-2022

Thanks. Happy to be wrong about “still dropping” but wondering if post pandemic expectations regarding longevity aren’t a factor.

“Happy to be wrong about “still dropping” but wondering if post pandemic expectations regarding longevity aren’t a factor.”

From my perspective, the answer is “surely.” US life expectancy is surely a factor. Life expectancy in the US is by far the lowest among the G7, US life expectancy was lower in 2022 than in 2004.

Again, US life expectancy was lower in 2022 than in 2004, and is far lower than in the G7 or European Union:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1pkwn

January 15, 2018

Life Expectancy at Birth for United States and European Union, 2000-2022

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1ads0

January 4, 2020

Labor Force and Population with a disability, * 2017-2024

* Age 16 and over

(Indexed to 2017)

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=16TwF

January 4, 2020

Labor Force with a disability, * 2017-2024

* Age 16 and over

(Indexed to 2017)

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=16TO1

January 4, 2020

Labor Force men and women with a disability, * 2017-2024

* Age 16 to 64

(Indexed to 2017)

I read this carefully but never found the words “life expectancy”…

[ This raises an important question, that remains after I have set down data on life expectancy and disability. Also, what role did productivity pay?

I appreciate the questioning of the article, and will do more questioning of my own from here. ]

Looks like the reports try to pick a kernel of truth from a pile corn.

Lets try to identify the large animal called inflation through a close microscopic inspection of mud found nearby.

Maybe inflation is caused by a misunderstanding of data structures — no need to worry that the dollars you work hard for, don’t go as far. Once the data is understood, you can be sure that the best minds will be put to use in some fashion.

A couple of reasons how the surge in retirement was possible:

Asset bubbles inflated, even with the employment and supply chain destabilization.

Also, this is a generation that still has some people with pension benefits (not only SS).

I suspect that combined with stock run-ups, more people are taking advantage of the “rule of 55” (or even rule of 50 for some people) that lets you take money from your last employer’s 401k with a penalty. I’m starting to think about it!

The big issue I think must be healthcare.

I retired at 65 which was a few years earlier than I planned, for personal reasons. Screw the economy I just like to sleep in and no more commuting.