Yves here. When McKinsey is as wrong as it is in predicting labor scarcity as a new normal (as the post shows, it isn’t even a current condition), one has to wonder why. On the one hand, there actually could be salutary motives, such as telling companies they have to start paying workers more, or stop being lazy in recruiting and focusing only on candidates who are presently or very recently did exactly the same job at a peer employer. But it seems more likely that this egregious misreading is the result of promoting AI, which is creating such a bubble that McKinsey either is getting or is eager to win its share of the lucre.

By Thomas Ferguson, Research Director, Institute for New Economic Thinking; Professor Emeritus, University of Massachusetts, Boston, and Servaas Storm, Senior Lecturer of Economics, Delft University of Technology. Originally published at the Institute for New Economic Thinking website

Every so often a publication comes along that more or less perfectly captures the Zeitgeist of world business elites. So it was on the 26th of June when the McKinsey Global Institute issued a new report: “Help Wanted: Charting the Challenge of Tight Labor Markets in Advanced Economies.”

The message its few pages of charts and text deliver is dire indeed: “Labor markets in advanced economies today are among the tightest in two decades, not merely a pandemic-induced blip but rather a long-term trend that may continue as workforces age.”

This constraining labor market, the report claims, “means forgone economic output,” since employers are not able to “fill their excess job vacancies.” “Companies and economies,” the authors warn, “will need to boost productivity and find new ways to expand the workforce. Otherwise, they will struggle to exceed—or even match—the relatively muted economic growth of the past decade.”

Less than two weeks later, on July 5, the United States Department of Labor released its “Employment Situation Summary” for the month of June. Lost in a wave of mostly upbeat press coverage were two striking facts utterly incongruent with the McKinsey report’s claims. Firstly, unemployment had risen to its highest point since November 2021: 4.1%. Even more awkwardly, Long Term Unemployment among the unemployed had spiked to 22.2% — more than five percentage points above its February 2023 low of 17.5%.

The measure of unemployment highlighted in the June release is the “narrow” measure, sometimes referred to as “U3.” It excludes many workers who we and many other analysts have long insisted should also be counted, such as discouraged workers and those working part-time because they could not find a full-time position. At no point during the pandemic did that “wider” measure, “U6,” in Labor Department parlance, ever fall below 6.7%. Since July of 2023, it has fitfully risen to 7.4. This means that, in June 2024, there are more than 13.1 million American workers willing to work but without a job.

These data are for the United States, but the situation in other developed countries is comparable; indeed, in many countries, the numbers are even more adverse to the McKinsey view. The authors of the report acknowledge that labor markets in some big countries, such as France and Italy, are not very tight, but they minimize the discrepancies, claiming that those are in fact tightening, too, just more slowly.

Rates of unemployment across developed countries differ and bounce around, as one might expect. But the June OECD figures (mostly reporting figures for April that OECD tries to make as comparable as possible), indicate that unemployment rates in most of developed countries run above current US rates and are trending up.

So how does McKinsey justify its conclusion that labor markets are tight and likely endemically so? The answer is simple: It ignores actual unemployment and instead builds its case in terms of data for “job vacancies.”

We have observed before that resorting to data about job vacancies became popular among mainstream economists as the much-touted Phillips Curve relation between unemployment and inflation broke down. And that a close look at US data raises deep doubts about these data’s reliability over time.

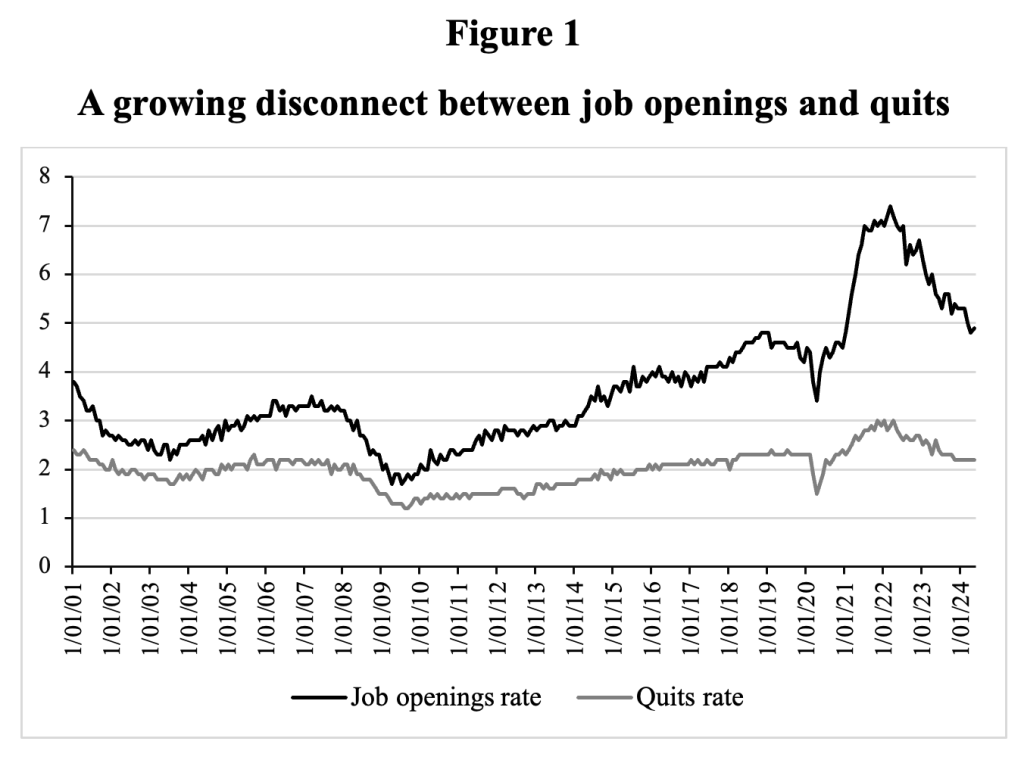

The emphasis McKinsey places on these numbers makes it worthwhile to reopen the case, so consider Figure 1. This plots the “job openings rate” and the “quits rate” since the beginning of this century. The first of these is computed by dividing the number of job openings by the sum of employment and job openings; the second refers to the percentage of workers who voluntarily leave their jobs each month. We are interested in the job openings rate because that is closely related to the job vacancy ratio, which is the ratio of job openings to unemployed workers.

Before 2010, the relationship between vacancies and quits was relatively stable. Between 2010 and 2019, however, the job openings rate began to surge relative to the quits rate. During the pandemic the relationship between the two indicators diverged markedly: as job openings rocketed upward, the quits rate remained rather steady.

Source: FRED database

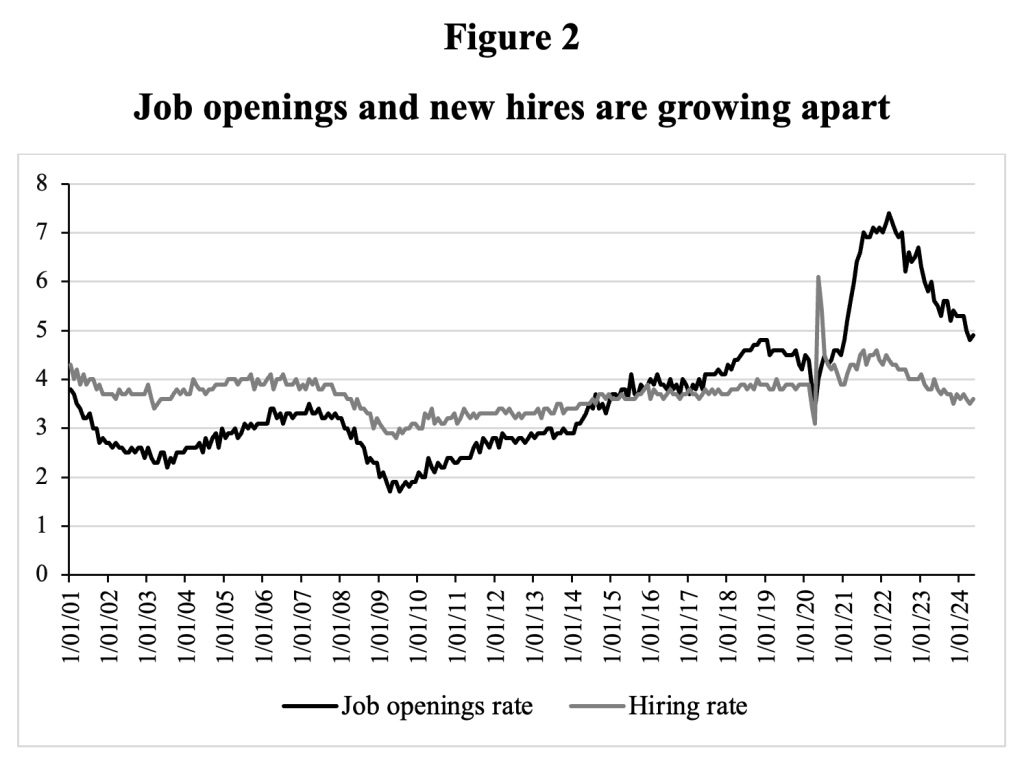

Similarly, the job openings rate and the hiring rate have grown apart, as is shown in Figure 2. Both moved closely together from 2001 to early 2020, but then the job openings rate almost doubled, whereas the hiring rate held fairly steady.

Source: FRED database.

These disparities raise further doubts about the reality of the sudden rise in the number of posted job openings. We could as well have pointed to the job-finding rate of the unemployed or any other labor market measure to show the very exceptional behavior of the job openings rate during 2021-2024.

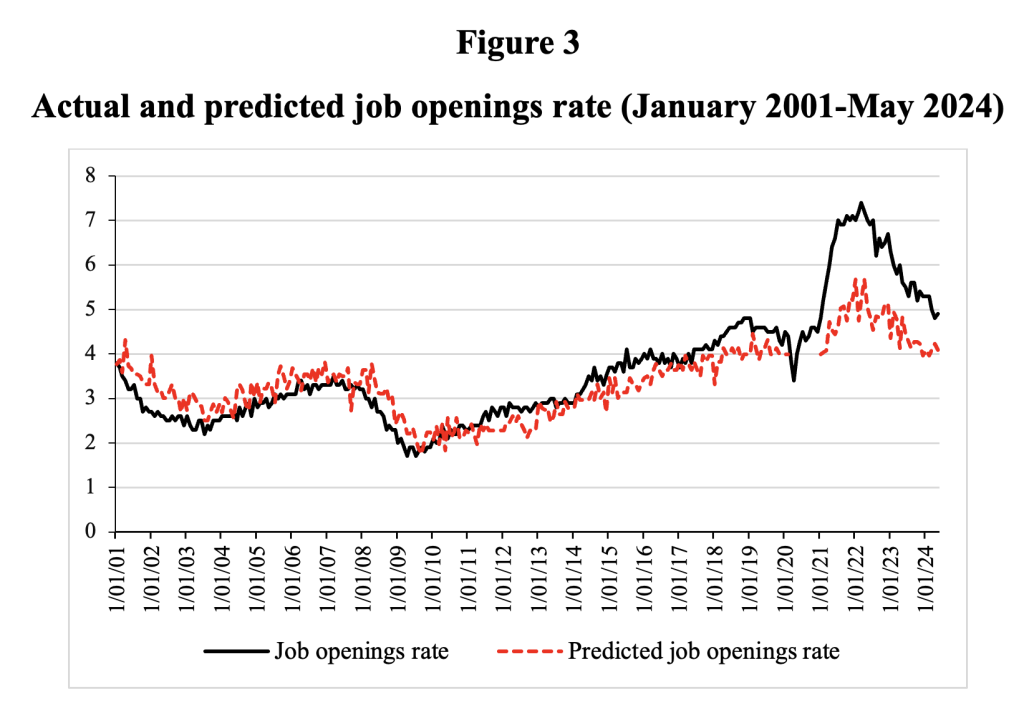

Figure 3 shows just how unusual the situation was. It presents a “predicted job openings rate,” which we computed assuming that the relatively stable relationships between the job openings rate and the quits rate (Figure 1), and the hiring rate (Figure 2) that existed during January 2001-December 2019 persisted during 2020-2024.[1]

It can be seen that the “predicted job openings rate” closely tracks the actual job openings rate from January 2001 to December 2019, before diverging dramatically from the actual openings rate from January 2021 to May 2024. The “predicted job openings rate” peaks at 5.7% in April 2022, far below the actual peak in job openings of 7.4% of total employment in March 2022. Based on trends in actual quits and actual hires, the “predicted job openings rate” is almost 25% lower than the recorded peak job openings rate.

Source: Authors’ estimations based on FRED database. Note that the predicted job opening rates for the twelve months of 2020 are not included.

It is clear that during the pandemic the behavior of the recorded job openings rate has been anomalous relative to other conventional indicators of labor market activity. This should have raised at least a yellow flag for McKinsey and other economic analysts. Focusing on one anomalous indicator while ignoring contradictory evidence amounts to (inadvertent) cherry-picking.

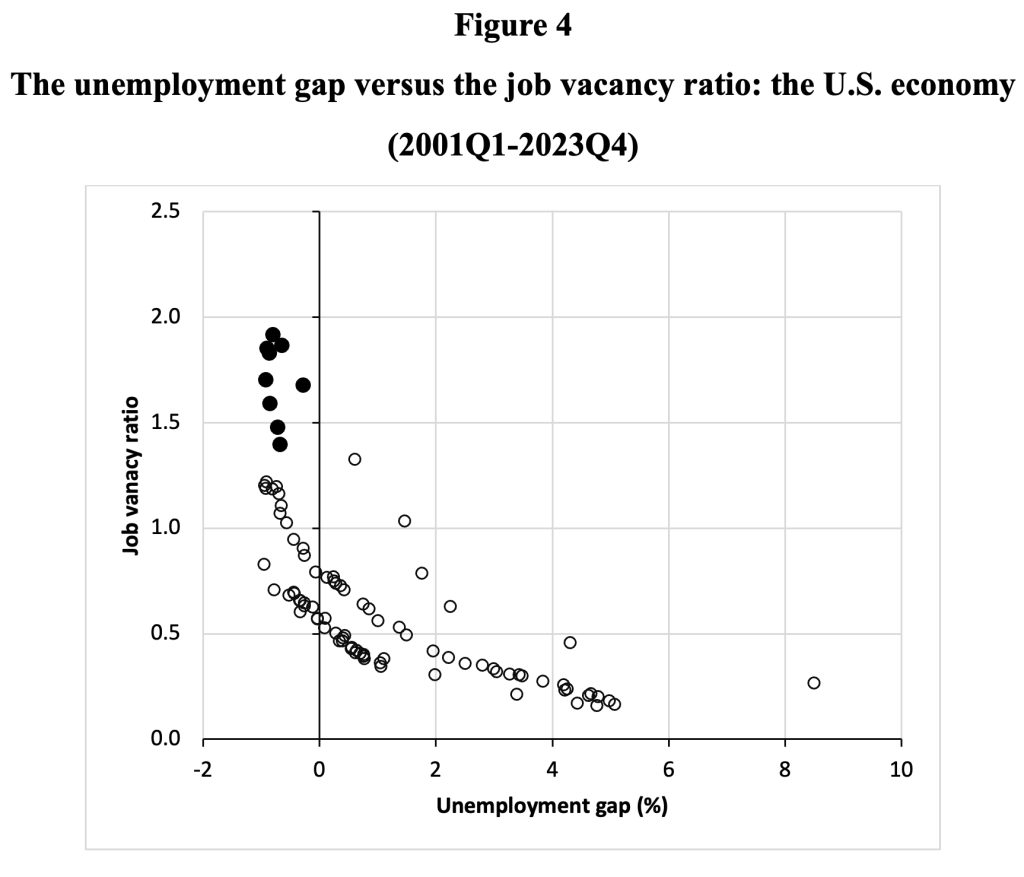

To put the final nail into the coffin of the vacancy ratio as a serious index, consider Figure 4, in which we plot the unemployment gap against the official job vacancy ratio. Again, it is clear that the sharply elevated vacancy ratios during 2021-2023 do not correspond to a considerably tighter U.S. labor market as measured by a more strongly negative employment gap.

Federal Reserve economists Mongey and Horwich (2023) have noted this anomaly as well, pointing out that the data on U.S. job openings have become disconnected from other indicators, seriously complicating the labor market outlook.

Source: Calculated based on FRED database (series UNEMPLOY; LMJVTTUVUSM647S; UNRATE; NROU). The black dots indicate the observations for the most recent quarters 2021Q4 – 2023Q4, during which the PCE inflation rate increased sharply. The unemployment gap is measured as the percentage point difference between the actual unemployment rate and the NAIRU (as estimated by the CBO).

One plausible factor in skewing the job openings rate (and the vacancy ratio) is that digital technologies have dramatically lowered the cost to employers of job posting, recruiting, and evaluating candidates. As firms have become familiar with using the internet, they have begun experimenting with strategic uses of their newfound powers. Over time, the result has been an increase in dubious postings.

In the U.S., the basic data come from Labor Department surveys. The surveys require that firms are actually advertisingfor work and that a real position exists that could be filled within 30 days. While research into this area has only begun, some conclusions seem relatively safe. Firstly, some decay in data quality could be innocent. For example, notices for job posts may remain on the internet after they have been filled or the search has been canceled, sometimes for long periods. Some firms also post external job notices for positions they actually intend to fill internally.

Secondly, efforts to scam job seekers by outsiders manipulating other firms’ posts is enough of a problem that researchers are now investigating how artificial intelligence methods might be used to defend against them. For this, the firms themselves can hardly be blamed.[2]

However, recent survey evidence suggests that many firms now advertise positions with no intention of any imminent hiring. Such information allows them to track the replacement cost of their current workforce in real-time and remind current employees that they could be dispensed with. “In some instances, hiring managers said their goal is to signal to current employees they are replaceable. Nearly 60% of companies surveyed said they collected resumes to keep them on file for a later date, with no intention of immediately hiring anyone.” Analysts familiar with company practices also suggest that being able to point to a notice unfilled for a long time can sometimes help companies make special cases for particular employees they want to hire, particularly if they need visas.

Estimating the percentage of faux ads is hardly an exact science, but evidence suggests that they increased slowly in the years before the pandemic, then shot up dramatically once COVID hit. The practice is now common enough to raise hackles among job seekers (and their counselors) who applied for positions they believed were offered in good faith.

The McKinsey study treats these data with no sense of their fragility. It takes no account of faux positions or their likely seismic increase once COVID hit. It simply displays a rising plot of vacancies in the United States and other major countries. We think it is worthless as evidence about the real state of labor markets, as Figures 1 to 4 have already shown.

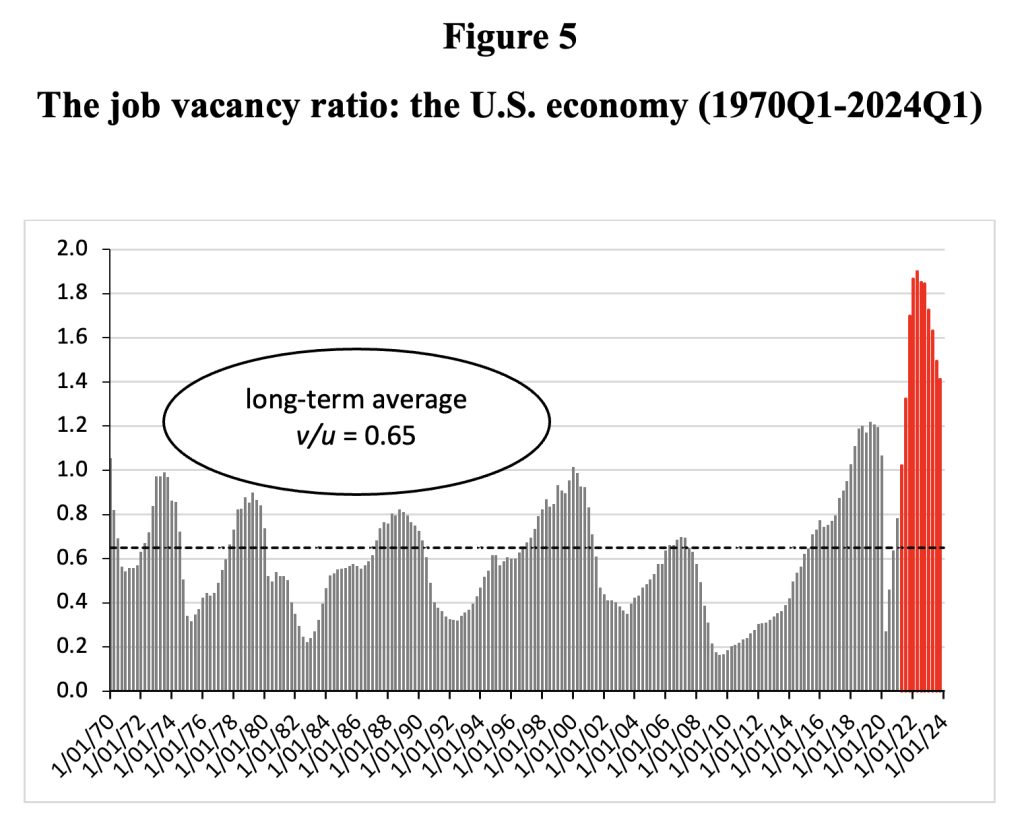

Even on its own terms, though, the data can hardly qualify as serious evidence. Time series analysis is notoriously a black art and disentangling real trends from noise is a perennial challenge. The McKinsey study’s time series just doesn’t make the grade. The study plots observations from 2015. If you extend the jobs to vacancy data back to 1970, as we do in Figure 5, there is no evident trend in the data. The job vacancy ratio has shot up repeatedly over time, for instance during 1997-2000 and during 2017-2019, but also dropped off repeatedly to levels below its long-run average.

Sources: Calculated based on FRED database (series JTSJOL and UNEMPLOY) and Barnichon (2010). Notes: The data for 1970Q1-2000Q4 were constructed by Barnichon (2010). The job vacancy ratio is the number of vacancies per unemployed worker.

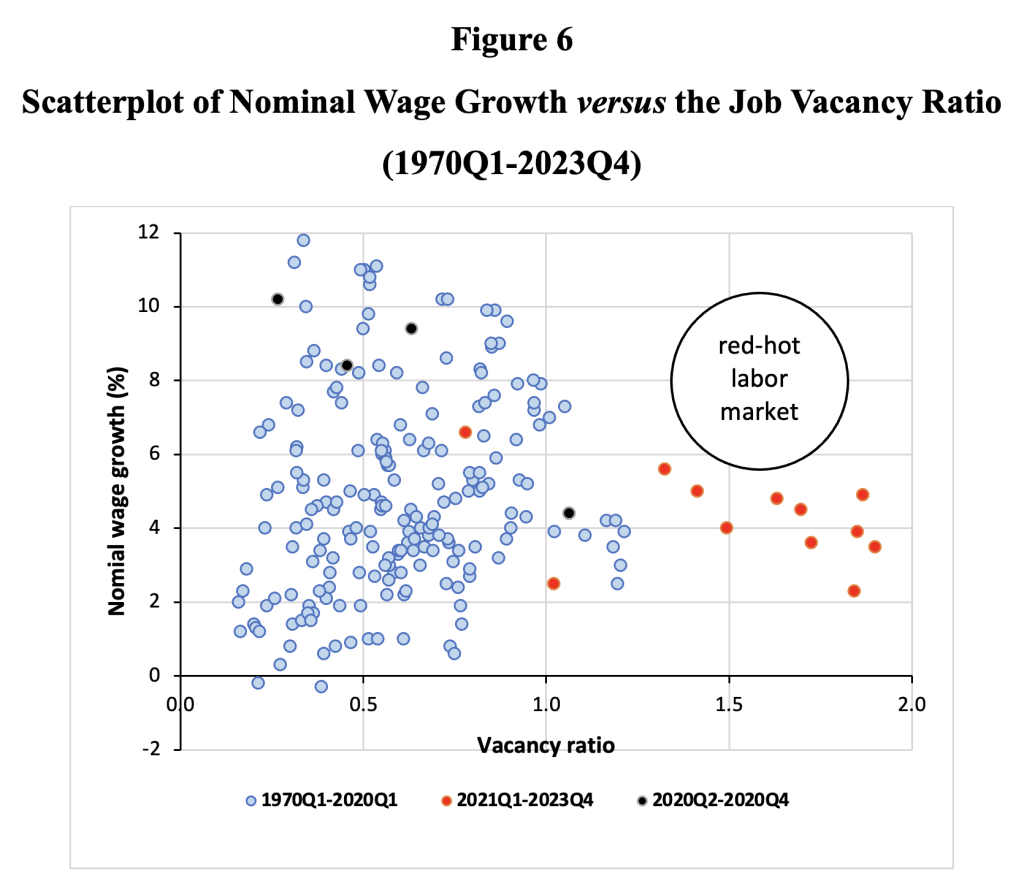

A final piece of evidence confirms that the extremely high vacancy ratio in recent years did not reflect the true state of the U.S. labor market. Figures 6 and 7 display this evidence. Figure 6 scatterplots the job vacancy ratio against nominal wage growth during 1970Q1-2023Q4. It is obvious that the extremely elevated vacancy ratios of recent times did not lead to exceptionally high nominal wage growth, as we have emphasized in several previous studies that have critically analyzed highly advertised claims to the contrary. Rather the opposite: nominal wage growth during 2021-2023 was close to the long-term average.

Sources: Calculated based on FRED database (series JTSJOL, UNEMPLOY and PRS85006101) and Barnichon (2010). Note: quarterly nominal wage growth is measured by the growth rate of hourly compensation for all workers in the non-farm business sector.

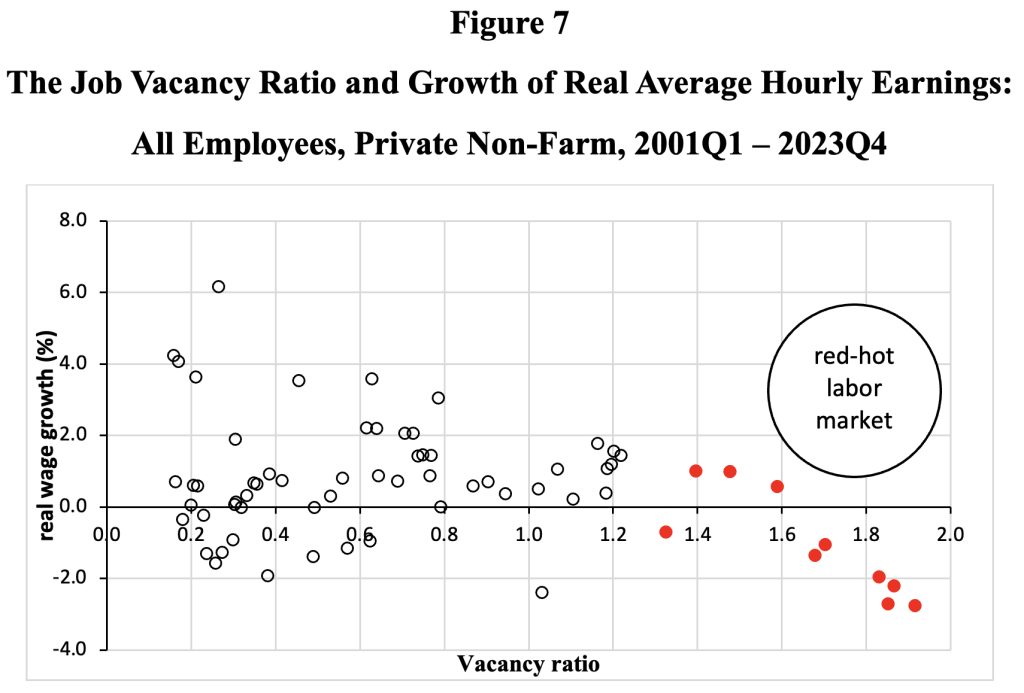

Figure 7 plots the job vacancy ratio against the growth of real average hourly earnings during 2001Q1-2023Q4. It is again apparent that the unprecedentedly high job vacancy ratios did not lead to high real wage growth. On the contrary, the growth rates of real average hourly earnings were negative, right when the vacancy ratio was at its highest level.

There is no doubt that the rise in the job vacancy ratio is spurious, i.e., not related to real labor-market tightness, but instead most likely caused by a sharp increase in manipulative job postings.

Sources: Calculated based on FRED database (series JTSJOL and UNEMPLOY) and Barnichon (2010). Notes: The data for 1970Q1-2000Q4 were constructed by Barnichon (2010). The job vacancy ratio is the number of vacancies per unemployed worker.

McKinsey, finally, makes the laughable point that “at the economy level, we estimate that GDP in 2023 could have been 0.5 to 1.5 percent higher in the biggest advanced economies if employers had been able to fill their job vacancies.” The reason, supposedly, is that “companies may need to turn down orders because they can’t hire enough workers to satisfy demand.”

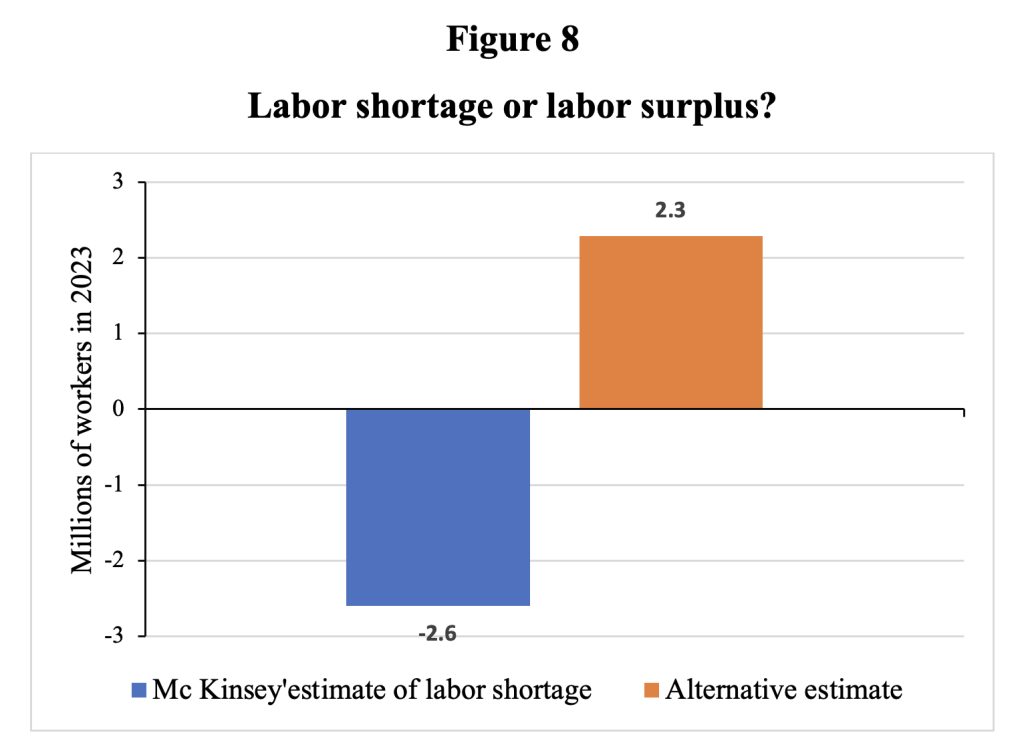

McKinsey assumes that labor scarcity is constraining output: firms cannot step up production because they cannot fill their job vacancies. This can only be true if there really is a lack of workers. According to McKinsey, the U.S. suffers from a labor shortage, because the number of job vacancies is higher than the number of unemployed workers. We do not need to repeat our arguments, made above, for why the data on job openings have become unreliable and polluted. McKinsey’s claim is wrong for yet another reason, however. The measure of unemployment (called U3) used in the study also does not represent a good indicator of workers without a job.

The reason is that U3 excludes many workers who should also be counted, such as discouraged workers and those working part-time because they could not find a full-time position. While around 6.1 million American workers were unemployed in the year 2023 according to the narrow definition of unemployment, in reality, more than 11.6 million workers were without a job, based on the broader (U6) definition of unemployment. As is shown in Figure 8, rather than having a labor shortage, as McKinsey wants us to believe, the U.S. had a sizeable labor surplus of more than 2.3 million workers in 2023 – when compared to the flawed and polluted count of job openings. Given the “inflated” number of job vacancies, the real labor surplus is still higher. All this means that McKinsey’s estimate of output foregone due to the misdiagnosed labor shortage is bogus.

Sources: McKinsey (2024); the alternative labor surplus measure is estimated using data from FRED on “Total Unemployed, Plus All Persons Marginally Attached to the Labor Force, Plus Total Employed Part Time for Economic Reasons, as a Percent of the Civilian Labor Force Plus All Persons Marginally Attached to the Labor Force (U-6)”.

These are not the only difficulties we see with the McKinsey report, especially in light of the vast changeover to electric vehicles now underway in the world automobile industry. This will likely reduce employment in both the US and Europe. Other “hidden labor reserves” also exist in Europe and the US. The McKinsey report itself notes that reasonable cost daycare could allow many more parents, mostly women, to participate much more fully in the labor force. We also doubt very much that the aging of the workforce explains nearly as much about recent labor market participation as often claimed, though that topic is so important it will have to be reserved for another occasion. And there are steady streams of immigrants, now apparently undercounted in the United States by several million. Claims of a coming labor shortage just do not hold water. The real place where “help wanted” signs should be posted is for better estimates of job vacancies.

Notes

[1] Technically, we performed a simple Ordinary Least Squares regression of the job openings rate as a function of the hiring rate and the quits rates (using monthly data for the period December 2000-December 2019; n= 229).

[2] Some of these problems and others not mentioned here, such as multiple listings of the same position, are well understood and serious efforts to track positions typically try to take account of them.

My college-educated, PMC TDS sisters and relatives, born just a little too late to look the evil of the Vietnam War straight in the eye, similarly do not look the U6 rate straight in the eye.

They are now retiring from McKinsey-esque gigs with the likes of Siemens and NSF. They see MAGA as evil, rather than pathetic. It’s hard to convince McKinsey of the facts, when their salaries depend upon not seeing them.

I had minor encounters with McKinsey´s world 30 years ago:

A friend from high school graduation was intent on becoming an artist. Then, without any explanation, she suddenly started to work for McKinsey instead. And a few weeks later, she disappeared. I never heard of her again. Just gone.

A little later I contacted McKinsey to do some media art project about the new economic elites. I contacted others too, like Siemens and various banks. The only one that refused to talk to me – this was still a different era, when companies and the public did not regard every picture made, every square meter in public space as cause for legal action over personality rights – was McKinsey. They only responded in an email that they would not speak to the media. At. All. Be it art or not.

Later when doing some interviews I was told by economics students that McKinsey was like a cult or sect. Worse than secret intelligence. (I once had an encounter with German FBI, frankly they were no better.)

p.s. One of the most impressive private art collections I saw was underground in the halls of Germany´s most powerful insurance companies, Münchner Rück. It´s like a parallel universe.

A few meters below the city´s centre. Employees walking past most expensive artefacts. I imagine McKinsey to be the same. But unlike the insurance company they wouldn´t let me in. Naturally realizing that these are the places where policies concerning all our lives are shaped is very very very scary.

Another good analysis from Ferguson and Storm!

Some interesting reasons outlined in the article as to why advertised vacancies may not match up with real job offers – I’ve certainly heard a number of stories recently of people applying for jobs they are very well qualified for, but not even getting an interview. It makes sense that many of these adverts are just fishing expeditions by HR departments, or perhaps just for show for when they already want to appoint someone internally. I also think that mass advertising for non-existent jobs is also a way of justifying work visas.

Again anecdotally, I think many companies now have narrowed down their criterial for potential hires as they see so many new employees as disposable. The idea of hiring smart, capable people and then training them in is considered a bit old fashioned. They want someone who can be ‘productive’ from day one, but gotten rid of in a year or two if required. This inevitably tightens up their search criteria.

Whichever way you look at it, we are in the strangest economic situations I can remember – its not just in the US – in Asia and Europe you see this weird mismatch of businesses complaining they can’t get staff, while we see lots of unemployment or underemployment in specific cohorts (most obviously recent graduates). Something has broken and conventional measures are not picking it up.

“Something has broken and conventional measures are not picking it up.”

1) The job posting online with algorithm selection heightened all the worst aspects for a job hunter. And encourged more exploitative behavior from employers.

2) There is culture shock from demographic changes.

I am surprised, after scrolling through the comments, that nobody has mentioned the effect of the PPP (Paycheck Protection Program) rolled out during Covid. All of those employers that took out loans that were forgiven in advance with the requirement that they not lay off any employees- but had the loophole large enough to drive a heard of elephants through that stated that as long as they were actively seeking to hire employees they would not be punished if they could not find them. So all these employers cut employees, then continually advertised the positions without ever filling them. So they basically put not only the loan into their pockets, but the funds resulting from cut costs into their pockets as well. Then they blamed the degradation of service and production output on lazy workers: “Nobody wants to wurk anymore”. Meanwhile this false outcry caused the working class to turn on itself.

Anyway, looks to me like the time that this divergence occurred/accelerated was about when the PPP went into effect. I am just a hick from Appalachia though, so maybe I am imagining it.

My own suspicion is that during the pandemic a non-negligible % of the labour force seeing no prospects in traditional employment, sought self-employment income streams and have thus taken themselves out of the labour market and, ever since, employers have been wondering where they’ve gone, have seen applicant numbers down and consequently have trying various things, including deception, to attract applicants.

The sharp increase in manipulative job postings probably coincides with an increase in cynical gamesmanship among employers, but it probably also indicates some degree of sentiment among employers that the best employees are getting more expensive and harder to find (at least among the native population). If that sentiment exists then it is not surprising McKinsey wants to service it.

Underneath the noise, I would expect there to be at least a little bit of a mismatch problem across the labor market right now. If Covid brain damage is really a large-scale phenomenon, then a growing number of skilled workers are no longer able to do the last job they had effectively. Even if Covid brain damage is less widespread, the most capable employees might be the ones most likely to exit the labor force through early retirement or self-employment.

Anecdata: at my evil giant multinational, I have trouble finding decent candidates because HR will not let me look at anything that has not gone through their AI and other pre-selection filters. The only way I can get some talent that I actually want to work with is to go through my personal network and then shepherd that CV through HR and back to me, with a bunch of steps in between. Of course there is a mandatory DEI part of all this and those metrics are like a black box, don’t even ask. I’ve been docked points when a diverse member of my team moved to another firm because I could not manage to convince (or even reach someone coherent in) HR that she needed a raise over market level and that it was extremely important for retention, if they wanted a really diverse work force. It is a nightmare. I’m sure that there are hundreds of good CVs out there that I never see. One thing though – once you’re in, you’re good and can move around but don’t count on much increase in salary y/y.

More anecdata: when I was checking around to find something interesting for a lateral right after the Omicron wave, the companies who gave the best interviews and seemed to really know what I was about at the get-go (from just reading my CV) were Chinese telecoms or tech cos.

“The only way I can get some talent that I actually want to work with is to go through my personal network and then shepherd that CV through HR and back to me, with a bunch of steps in between.”

And is that even more the case if the candidate is over 40?

Short answer, no.

Long answer, I only hire senior, 15+ years experience. So even if the CV gets to me, it would be rare that anyone with less than that would get my callback. The junior people come through a different hiring channel, mostly directly from universities or internships, laterals or from acquisitions. Under 35 would not be able to do the work or would already be full of themselves from an options cash out. Which are sort of the same lol. Over 65, I’d definitely talk to you but would hope that you’d have a good reason for not wanting to leave the grind (hate that word) and do something else with the rest of your life.

My experience is that people over the age of 40 are often expected to have a professional network helping them to find new roles. And because of this expectation then there are those who ask:

Why does a person over 40 not have a professional network helping him/her find a new job? Is there something wrong with this person or why does he/she not have a professional network helping him/her? Is nobody who knows him/her willing to stick out their neck (recommending someone comes at a risk) for this person?

And since those who deem the lack of professional network be suspicious or possibly even a red flag then people over 40 who try the ‘official’ path into a new job might be filtered away. Connections help and a lack of connections hurt.

Of course it depends on the industry and location so my experience might not be relevant for many but it might be worth considering anyway.

I am a bit surprised “ghost posting” (the act of posting job openings you never intend to fill just to show investors that the company is “growing”) wasn’t mentioned since its become fairly topical among those looking for jobs.

First-line managers all want more headcount to mollify their overworked staffs. HR wants more postings to protect their bullsh!t jobs. Upper management doesn’t want to hire simply to improve product. For them, lower headcount = higher ‘productivity’ = higher bonuses/stock options. Ibgybg.

Pretty much, and from what I can tell “ghost posting” happens more frequently in tech startups than say construction work.

I think either AI is failing DoL or DoL is failing at using it!

Can you say AI don’t work because it cannot compensate for asking the wrong questions?

My opinion is web searches are less pleasant (retired I do not need the data for work) with the AI schema bc it is too sensitive to how the question is posed.

Anecdotally; Boston MSA.

Son in law operates a sand and gravel business. Seasonally slow after good years with all the money from the stimulus money. Maybe some projects pulled forward by all that money?

His sense from conversations etc.: labor is too high and scarce, transport bc fuel and labor is very high, spec building is down (concerns on rates and recent price spikes) and government hard projects (roads etc) are down.

Another acquaintance is (plans to) selling a property rather than developing it.

Suggests, even in slowing housing trade, labor is expensive.

The average 1 bedroom in Boston is like 3k. So yes finding someone to work for you that has to pay the rent or mortgage is going to be expensive.

I seriously doubt this will reduce employment by much. Within my own region (Southern Ontario, Canada) the automotive plants simply switched from ICE to EV. They retooled the existing production lines, the auto bodies and chassis themselves were always changing anyway, engines always modified, with each new model they were building for. For everything else unique to the EV production line the labour force was simply reskilled and supply chains adjusted to source new inputs. People were moved from the ICE lines to EV.

I do see mechanics threatened as logistics fleets realize the cost savings in maintenance fees of EV over ICE – 40% of costs are in maintenance and parts for trucking fleets. I do see the mechanic career threatened worldwide but only once ICE cars become scarce, which is not the case now.

And yes, there is no need for fuel tanks, fuel lines, exhaust, radiators, hoses, starter motor, alternator, no need for pistons, crankshafts, belts, pulleys. How much labour would be lost from these suppliers, though? Much of this will have been mass produced from assembly lines anyway.

But otherwise the automobile industry will chug along with the same production lines and the same (albeit reskilled) labour force numbers, I don’t see much impact.

The section you quote did not specify where the employment reduction would take place, as in at OEM versus among all the enterprises that maintain cars. So your criticism is a big straw man.

Apologies, I probably should have clarified I was dealing with that sentence more in isolation rather than as anything that would detract from his larger thrust. Even if he had specified, it doesn’t (in my view) invalidate anything else he has written, he’s not wrong, so any straw dogs are inadvertent on my part.

The McKinsey report speaks to the shift to EV in the automotive sector, saying the transition has increased jobs and is contributing to an increase in the manufacturing sector footprint. Ferguson is here (tangentially, as an aside) saying otherwise. Again, this doesn’t invalidate any of Ferguson’s points, but just scribbling a light question mark in the margins here, in pencil not pen, and wishing he had expanded, but only from an edifcation point of view.

Interesting work. At the same time, US governments have been pumping money into the US economy at an average rate of $1 trillion per year since 2001, over $2 trillion a year in the last 7 years. Imagine how much the economy would slow down if that money wasn’t being pumped it.

Huge deficits let the American ruling class brag about how dynamic the US economy is.

I don’t buy the labor shortage narrative for a minute. We have a business surplus, with the working class increasingly being priced out of housing near where businesses are located.

You can only have so many artisanal restaurants catering to tourists who are staying in short term rentals that used to be relatively inexpensive downtown apartments where the restaurant workers lived before things get thrown seriously out of whack.

POV from the trenches : happy employees and sub-contractors are the best recruiters, no need for online job postings. In case of an urgent need to hire, a cash bonus for bringing new soul works well every time. Why would anybody waste time recruiting online ? From the practical point of view, recommend to dismiss results of online job posting analysis – it’s a phantasy world.

Cui bono? It’s impractical unless you (e.g. McKinsey, management) can sell the ‘analysis’ for big bucks.

Pithy introduction and good comments.

Nearly a decade ago I saw “phantom job postings” used extensively in Silicon Valley in order to game the H1b system to bring in low-wage workers from India. Jobs were being posted that required coding in an obscure protocol only taught in South India.

Obama would surreptitiously fly in to a semi-decommissioned military airfield, collect checks in Atherton or Portola Valley, and poof! Another 25K H1b’s magically obtained a presidential certification of “critical need” often to later be discovered with their passports confiscated baking nan.

Sorry, I am not American so could not understand your last sentence for sure. Are you saying that there was a conspiracy where a bogus need for computer programmers was manufactured to bring in cheap Indian workers ; to simply work in retail stores like Indian-owned bakeries?

Are you also saying that the Ex President also made money from this scheme?

Obama would surreptitiously fly in to a semi-decommissioned military airfield, collect checks in Atherton or Portola Valley, and poof! Another 25K H1b’s magically obtained a presidential certification of “critical need” often to later be discovered with their passports confiscated baking nan.

[ I suppose the problem is me, but this strikes me as absurd. ]

Translation? : Obama needed campaign contributions so he visited Silicon Valley. He got checks and approved lots more H1B visas. A lot of the H1B visa jobs were bogus, so cheap foreign labor undercut all sorts of jobs as all sorts of greedy companies got in on the goodies.

“Tight labor market” used to be the dog whistle for high interest rates, so one might expect high interest rates instead as the “new normal”. Don’t forget Powell and the corporate press blamed the inflation on labor market being too tight. I don’t see this as signalling to companies they should finally get some sense and stop the class war on workers, I see it as the opposite: let’s increase it. Let’s increase unemployment by not even thinking of hiring more workers, because they won’t be there or will be too expensive. Just get the AI snake oil or think about how to further reduce your labor force. Paraphrasing Greenspan, gotta keep growing worker insecurity growing!

I nearly fell off my chair laughing when I read that they based their analysis on counting advertised “job vacancies”.That’ll work….lol

USAJobs is a classic example of job postings where an internal employee has already been chosen to fill the position.

Due to various laws and policies, DoD sites (US Navy, for example) are often required to post jobs that are intended for internal employee advancement. I know this because two of my advancements happened exactly this way.

1) an advancement offered to me

2) “the job notice will appear in a week or so on USAJobs, please apply immediately.’

3) one month (or so) later, I take the position.

This is a very common scenario