Yves here. I am posting this piece despite the authors’ abject failure to consider the deep internal contradiction treating censorship as any way justified, worst of all in depicting it as a bulwark of democracy. This stance again illustrates how fearful ruling factions in the West have become and how they over-rely on messaging, as opposed to getting legitimacy from delivering concrete material benefits to citizens and operating bureaucracies competently, as fairly as possible given often conflicting demand, and in an efficient manner.

Admittedly, the authors are Swiss and Europe generally does not have free speech as central (at least historically) to the exercise of democratic rights. But it seems noteworthy that this orientation suggests that the US, perhaps by design, did not promote this key component of US democracy through its “democracy” promoting organs like the National Endowment for Democracy and Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

I trust readers will have some fun picking this article apart.

By Marcel Caesmann,PhD candidate in Economics University Of Zurich, Janis Goldzycher, PhD candidate University Of Zurich, Matteo Grigoletto, PhD candidate University Of Bern; PhD candidate Wyss Academy For Nature, and Lorenz Gschwent, PhD student University of Duisburg-Essen. Originally published at VoxEU

The spread of propaganda, misinformation, and biased narratives, especially on social media, is a growing concern in many democracies. This column explores the EU ban on Russian state-led news outlets after the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine to find out whether censorship curbs the spread of slanted narratives. While the ban did reduce pro-Russian slant on social media, its effects were short-lived. Increased activity by other suppliers of slanted content that was not banned might play a role in mitigating the ban’s effectiveness. Regulation in the context of social media where many players can create and spread content poses new challenges for democracies.

Misinformation, propaganda, and biased narratives are increasingly recognised as a major concern and a source of risk in the 21st century (World Economic Forum 2024). The Russian interference in the 2016 US presidential election marked a pivotal moment, raising awareness of foreign influence in democratic processes. From Russia’s ‘asymmetric warfare’ in Ukraine to Chinese influence over TikTok, autocracies are weaponising information, shifting their effort from outright repression to controlling narratives (Treisman and Guriev 2015, Guriev and Treisman 2022).

Recent work (Guriev et al. 2023a, 2023b) highlights two major policy alternatives democracies could adopt to counter this threat. One strategy relies on top-down regulatory measures to control foreign media influence and the spread of misinformation. The other addresses the issue at the individual level with media literacy campaigns, fact-checking tools, behavioural interventions, and similar measures. The first approach is particularly challenging to implement in a democratic context due to the inherent trade-off between implementing effective measures to curb misinformation and upholding free speech as a core principle of a democratic order.

Recent actions, such as the Protecting Americans from Foreign Adversary Controlled Applications Act passed by the US Congress in 2024, the EU’s Digital Services Act (European Union 2023), the German NetzDG (Müller et al. 2022, Jiménez Durán et al. 2024) or Israel’s ban of Al Jazeera’s broadcasting activity, demonstrate that democratic governments see large-scale policy interventions as a necessary and viable tool to counteract the spread of misinformation. At the same time, the rising importance of social media as a news source adds a new layer of complexity to effective regulation. In contrast to traditional forms of media such as newspapers, radio, or TV, which have a limited number of senders, social media is characterised by a large number of users that act as producers, spreaders, and consumers of information – changing their roles fluidly and thereby making it harder to control the flow of information (Campante et al. 2023).

To shed light on the effects of censorship in democracies, our recent work (Caesmann et al. 2024) examines the EU ban on two Russian state-backed outlets, Russia Today and Sputnik. The EU implemented the ban on 2 March 2022 to counteract the spread of Russian narratives in the context of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine. The unprecedented decision to ban all activities of Russia Today and Sputnik was implemented virtually overnight, affecting all their channels, including online platforms.

We investigate the effectiveness of the ban in shifting the conversation away from narratives with a pro-Russian government bias and misinformation on Twitter (now X) among users from Europe. To do this, we leverage the fact that the ban on Russia Today and Sputnik was implemented in the EU while no comparable measure was taken in non-EU European countries such as Switzerland and the UK.

Media Slant Regarding the War

We build on recent advancements in natural language processing (Gentzkow and Shapiro 2011, Gennaro and Ash 2023) and measure each user’s opinion on the war by assessing their proximity towards two narrative poles: pro-Russia and pro-Ukraine. We create these poles by analysing more than 15,000 tweets from accounts related to the Ukrainian and Russian governments. Using advanced natural language processing, we transform these tweets into vectors representing the average stance of pro-Russian and pro-Ukrainian government tweets. We use these as two poles of slant in the Twitter conversation on the war.

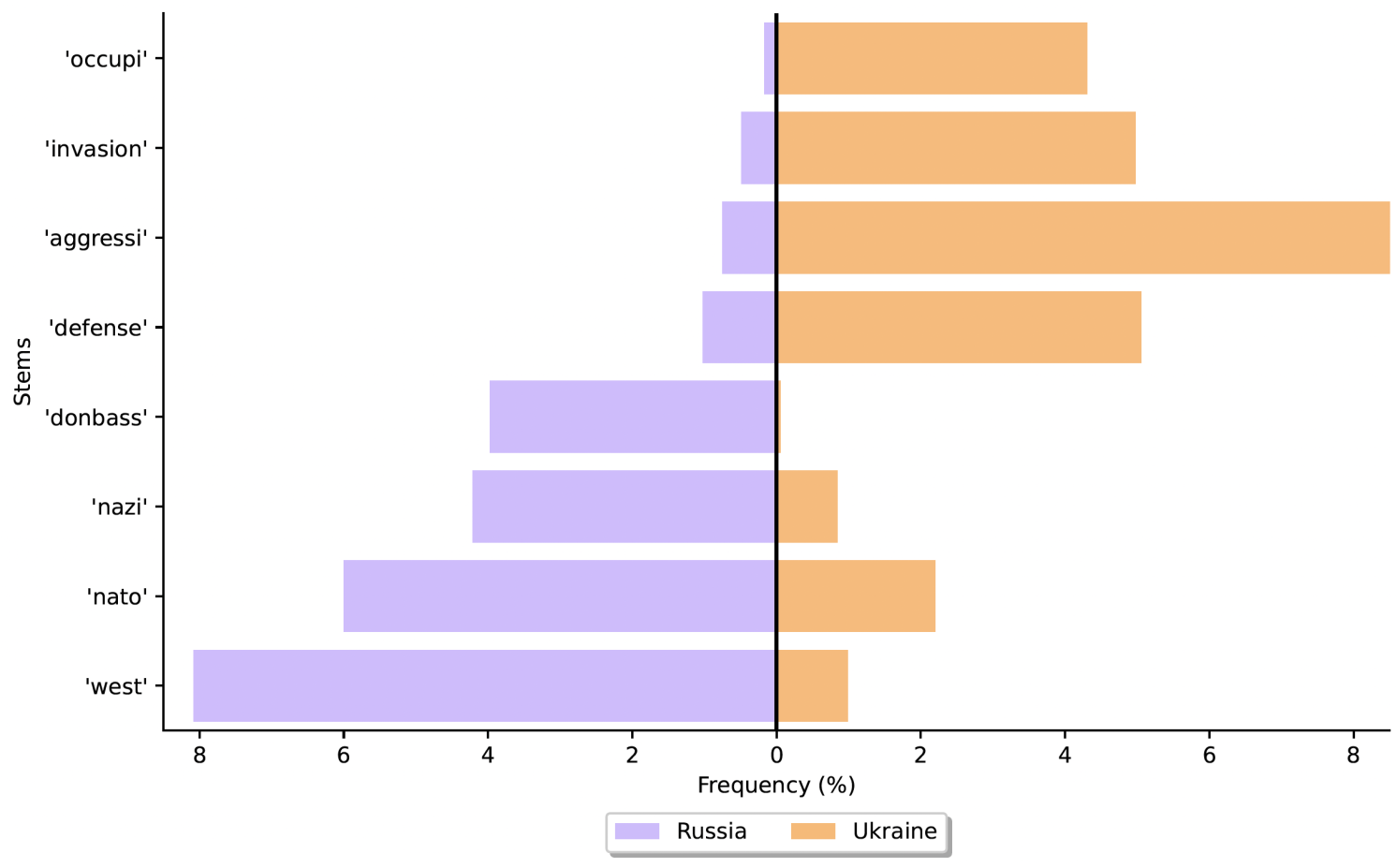

Figure 1 illustrates the content differences in government tweets, with keyword frequencies in Russian government tweets in purple (on the left) and in Ukrainian government tweets in orange (on the right). Keywords like “aggression” and “invasion” are used predominantly by Ukrainian accounts to frame the conflict as an invasion, while the Russian narrative describes it as a “military operation”. Other keywords like “occupy”, “defence”, “NATO”, “West”, “nazi”, and “Donbas” further highlight the distinct narratives of each side. These terms underline the slant in government content, making them effective benchmarks for our measurement.

Figure 1 Word frequency in the sample of government tweets

Note: Russian government tweets in purple (on the left) and Ukrainian government tweets in orange (on the right).

Next, we collect more than 750,000 tweets on the conflict in the four weeks around the implementation of the ban. We compute a slant measure for each tweet by calculating its proximity to the Russian pole relative to the Ukrainian one, centring it at zero. This measure takes negative values when the tweet leans towards the Ukrainian pole and positive ones for the Russian pole.

Censorship to Defend Democracy

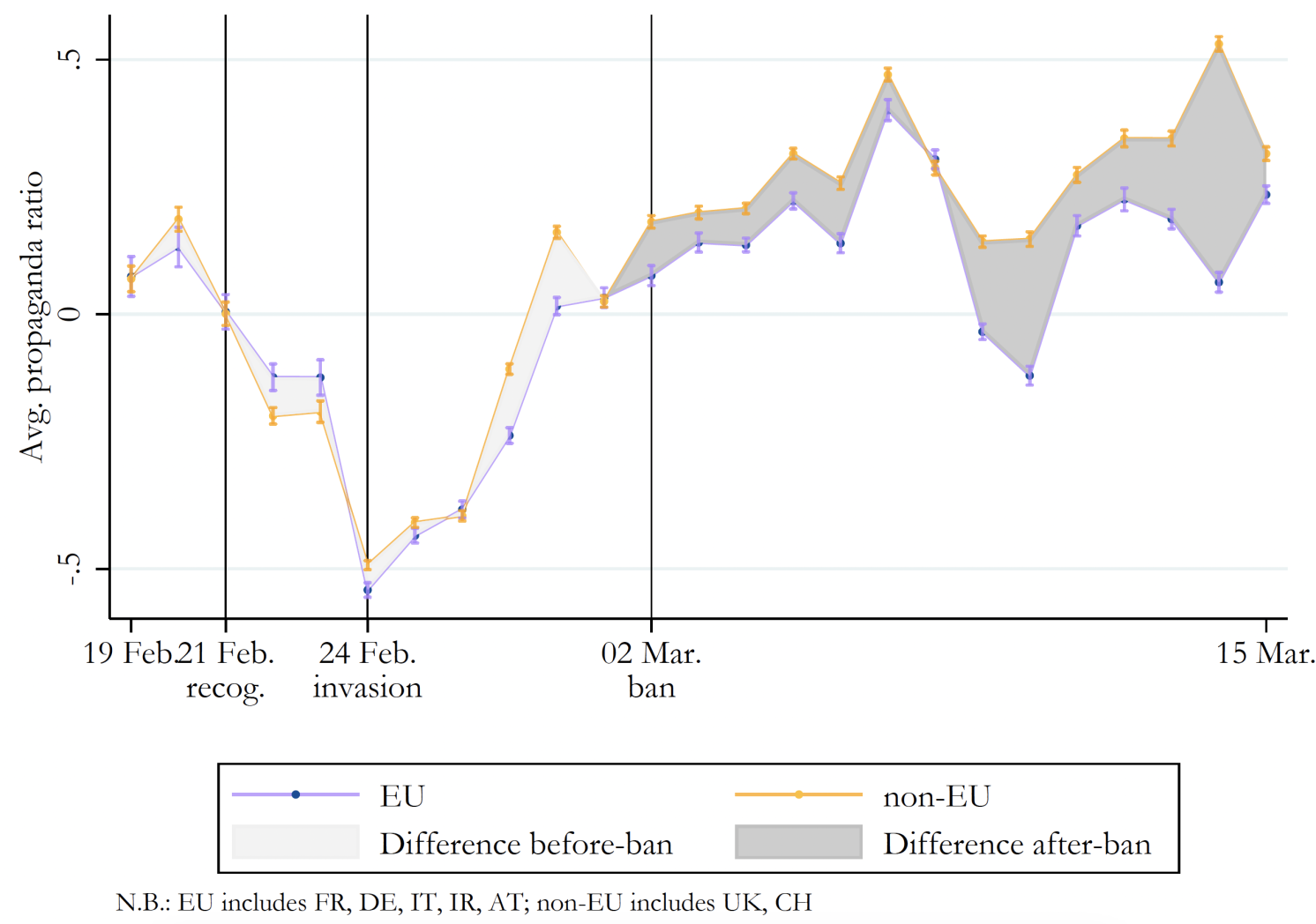

Figure 2 plots the time series of raw averages of average slant by users in the countries affected by the ban in blue and those not affected by the ban in orange. Our measure of media slant captures the dynamics of the online discussion. Until the invasion, the conversation was increasingly moving towards the pro-Ukrainian pole. The beginning of the invasion also coincides with mounting pro-Russian activity, most likely capturing the intense online campaign that flooded Europe and pushed the EU to a swift reaction. Overall, the raw data already suggests an effect of the ban on the spread of pro-Russian government content; we observe a growing divergence in the average slant between EU and non-EU countries after the ban is implemented.

Figure 2 Time series of our slant measure: Daily averages

To estimate the causal effect of the ban more systematically, we compare users located in the EU (Austria, France, Germany, Ireland, and Italy) that were affected by the ban to users located in non-EU countries (Switzerland and UK) that were not affected by a ban in the time of our study, using a difference-in-difference strategy.

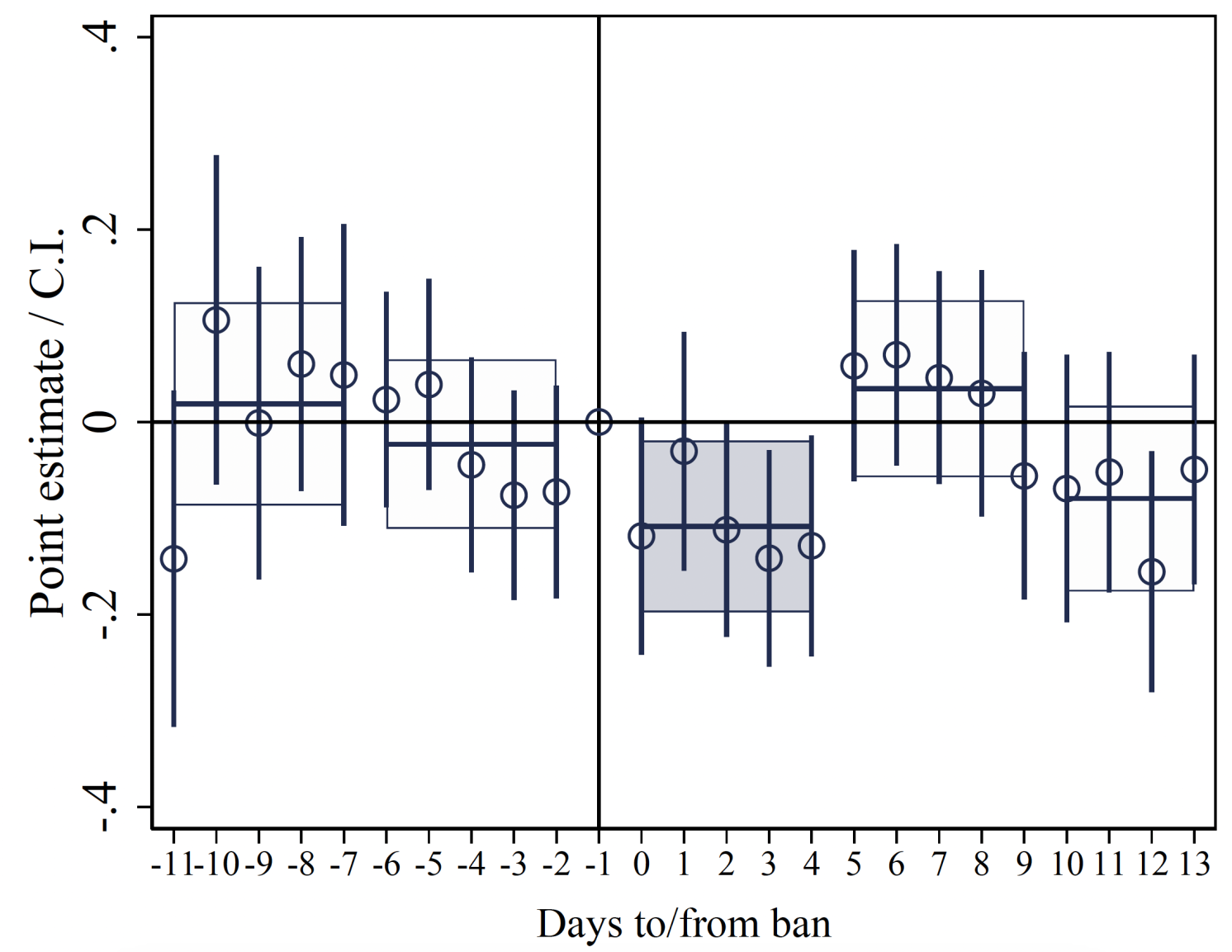

First, we focus on users who previously directly interacted (followed, retweeted, or replied) with the two banned outlets. Figure 3 shows the results of this analysis and indicates an immediate and sizeable effect of the ban, leading to a reduction in pro-Russian slant among users affected by the policy. Our estimates suggest that the ban reduced the average slant of these interaction users by 63.1% compared to the pre-ban mean with no clear existing pre-trends before the ban. In the paper, we show that this effect is most pronounced among users who were most extreme before the ban.

Figure 3 Daily event study on our slant measure: Interaction users

Censorship – a Viable Policy Tool?

A closer investigation into the temporal effect of the ban suggests that the effect is fading over time. While there is an immediate effect after the ban, even within the short time horizon of our study, the difference in average slant, between users affected by the ban and those not, closes a few days after the implementation.

We further study the indirect effects of the ban on users who did not directly interact with the banned outlets. We do find that the ban also reduced the pro-Russian slant among the non-interaction users. However, this happens to a lower degree, resulting in a decrease of approximately 17.3% from pre-ban slant levels, in contrast to the 63.1% observed among interaction users. Notably, we find a reduction in the share of pro-Russian retweets driving this effect. This finding suggests that the ban deprives non-interaction users of slanted content that they are able and willing to share.

Our results show that the ban had some immediate impact, particularly on those users who interacted with the banned outlets before the ban implementation. However, this effect fades quickly and is muted in its reach to indirectly affected users.

In the final step of our analysis, we investigate the mechanisms that might have compensated for the ban’s effect, effectively re-balancing the supply of pro-Russia slanted content. This part of our study particularly examines users identified as suppliers of slanted content. We provide suggestive evidence that the most active suppliers have increased the production of new pro-Russian content in response to the ban and thereby helped to counteract the overall effectiveness of the ban.

Our analysis complements insights from studies investigating small-scale policy interventions targeting the individual user (Guriev, Marquis et al. 2023, Guriev, Henry et al. 2023), by studying the effects of a large-scale policy alternative: governmental censorship of media outlets. Specifically, we provide evidence that censorship in a democratic context can affect content circulated on social media. However, there seem to be limits to the effectiveness of such measures, reflected in the short-lived effect of the ban and its more limited impact on users who are only indirectly affected by the policy.

Our study points to the crucial role of other suppliers who are filling the void created by censoring core outlets. This reflects the changed nature of media regulation in the context of social media, where many users can create and spread information at low costs. The ability and willingness of other users to take action seem to limit the effectiveness of large-scale regulatory measures targeting big outlets. Successful policy interventions need to account for these limits of large-scale regulatory measures in the context of social media.

See original post for references

Figures 1,2,&3 are blank. Censored?

No, the images apparently did not come over for you. I made some fixes and you should be able to see them.

“Censorship works, but not very well, so give it more money and perhaps we will be able to prevent people from knowing what we don’t want them to know”.

This comes from PhD candidates. Are they grown in vats, or something? I mean, I could have come up with better arguments in primary school.

Yes, these “PhD candidates” would seem to have a very promising future in the EU. The opening paragraph gives their game away, but the main point of this article is in its conclusion:

“The ability and willingness of other users to take action seem to limit the effectiveness of large-scale regulatory measures targeting big outlets. Successful policy interventions need to account for these limits of large-scale regulatory measures in the context of social media.”

Gotta plug those leaks by going after all the little guys more rigorously. “Censorship to defend democracy.”

US & G7 media have long been by, for, about & solely from a PMC/ Yuppie perspective. Consolidation, from K, J & C Street think-tanks & Rick Berman/ Hill+Knowlton style social networking advocacy solutions firms struck in plenty of time for 1984! That we were able to see IOF & settler’s sneering atrocity porn & Gaza reporter’s phone video, before they were murdered, enabled our evaluation of Likud’s hasbara & contradictory Israeli news sources made it onto OUR blog aggregators. Compare this with our sacrifice of Ukraine, HICPAC’s re-re-infection of workers, by pretending SARS-CoV2 is somehow OVER? We all are awakening, to check “X” for news (right before Naked Capitalism’s Links!) as we’d checked WSWS for COVID news & Moon of Alabama for Ukraine & individuals on social media for China, Sudan, Guyana… & corrupt, Oilgarch owned DUOPOLY & Likud’s media?

I’m a swiss citizen and working in Switzerland as a lawyer. I’m ashamed to read this piece written by swiss students. We have a constitution which says in Art. 16: “Every person has the right freely to receive information to gather it from generally accessible sources and to disseminate it.”

And for them the criteria to ban certain information is only whether it is pro russian or not. It doesn’t matter if it is true and accurate information.

Thank you for standing up for the reputation of Switzerland!

I am not sure they are all Swiss students — but European anyway (one of them makes his PhD in Germany, another one studied in Italy prior to working on his PhD in Switzerland).

After looking at their brief bios in the CEPR site, it appears that at least three of them are working on… machine learning techniques for text analysis (with topics such as “detection and analysis of hateful language”).

The most curious aspect is that one works for the “Wyss Academy for Nature” — an organization founded by famous Swiss billionaire Hansjörg Wyss (who lives in the USA), the University of Bern,the canton Bern, and the Swiss government — and mostly dedicated to the study, promotion, and implementation of a “green new deal” (with branches in Africa, Asia, America). Those with more knowledge of NGOs can have a look at their large list of partners and funders. I noticed the presence of Chatham House, Transparency International, and the Club of Rome.

Somebody working at that foundation on censorship is odd — the official goals of the Wyss Academy for Nature deal with approaches to counter climate change and biodiversity loss, and further sustainability — but perhaps it has something to do with their “Policy outreach and synthesis centre” area of competence.

Censorship to defend democracy sounds like an oxymoron. I get that misinformation is a big problem, but isn’t censoring just another form of control? It’s like the cure is worse than the disease. Instead of censorship, why not invest more in media literacy? Teach people to think critically and spot fake news themselves.

The operation was a success but the patient died.

The problem is that too many people *are* spotting the fake news themselves. The Powers That Be can’t have that. Their “media literacy” campaigns explaining why the New York Times is a reliable source and RT is propaganda have not worked. Thus the need for censorship – it’s for our own good!

Not sure why it should be an oxymoron at all. Democracy is what FDR called „ a weasel word“ and in Greek history and frankly until 20th Century ran on a restricted franchise. Universal suffrage suffers the public toilet problem if being open but usually soiled.

Attempts to restrict options – to avoid the Socrates hemlock matter – tend to require mass parties with Democratic centralism or simply Oligarchy with theatre in the Wizard of Oz model

What is today lauded as „Democracy“ is what GDR embodied with decisions made and communicated by organs of the State. That is why since 1980s The West has uniformly been proto-fascist and that was the design feature of the EU itself.

So in a world where French Values are embodied in Paris Olympic Spectacle or Birmingham Baal worship at Commonwealth Games, it is simply another AgitProp Slogan here in The Matrix

This is the sort of thinking we saw, historically, in communist circles in the early history of the Soviet Union and communist activists internationally. Censorship then became so common that it no longer needed a discussion during the Stalin period. It is also an argument I’ve heard coming out of universities in recent years in this country as well as the government and their allied social media companies. I believe it is here to stay.

I see the problem as much greater in the area of propaganda and mind-control by various media outlets. If you listen to any mainstream media broadcast the lies and bizarre mythical frameworks are getting worse. we are facing a new era of the Big Lie peppered with a swarm of little lies making the average person either wanting to ignore the propaganda (healthy) or be swept away in paroxysm of Orwellian anger at Emanuel Goldstein in all his flavors.

Hopefully, there will be enough of us to maintain the principles of Western Civilization to some degree before we blow ourselves in some version or combination of WWIII and/or civil war.

Is this pro-censorship vision normal in Swiss society or your universities?

Anyone censor Olympic opening ceremony nutsack guy in Switzerland or is just counter-narrative Russo-ukraine War stuff? Broadcasting bare french balls into Swiss citizens’ homes seems to have a political bent.

Is this a new development? Western media has never been more censored than it was during WW2

‘Nuff said…

The first para shows a (deliberate?) misunderstanding of the issue, by framing the problem as one of interference by other countries.

Yes, this interference happens, and has always happened. However, the current issue that goverments don’t like and are trying stop is actually different. I’ll redo that first sentence:

A piece decrying “propaganda” and “misinformation” has this deliberate falsehood as its second sentence. Irony is dead.

Marcel Caesmann, Janis Goldzycher, Matteo Grigoletto, and Lorenz Gschwent are liars.

Oh, the simpletons feeding the even more simple minded bureaucrats and politicians.

Firstly, RT & Sputnik cannot be truly described as pushing a Russian agenda. One only needs to hear Martyanov berating the outfits. I peruse them and find that is mostly not necessary to read beyond the title. Are focused mostly on facts and less on opinions.

What is annoying is the censorship applyied on social media, Reddit, Facebook, X, etc. With this censorship in play one cannot conduct any reasonable analysis to get an idea what people might actually be thinking. Because the message is being deleted from the get go. And then is the self censorship, with many people prefering to hold back rather than expose their well being to the hateful attacks of thought commissaries and dementors.

EU information space is becoming akin with what I experienced in socialist Romania. ANd in Socialist Romania, censorship was officially abrogated in 1974. Because, I was told by my ex father in law, editor and poet, by that time self-censorship was working perfectly…

The next step in EU is banning political parties that expose the wrong think, because the censorship doesn’t work at the ballot box…

Do an internet search on “AfD ban”.

That observation is consistent with what I saw in most “successful authoritarian” societies: everyone knows when to hold their tongue, so no censorship is necessary; the government and its agents know how to play retail politics well enough that they can almost always win fair elections–so no electoral fraud takes place; the government knows who the important social actors who need to be appeased and what price to pay…and pay them. Amidst all these, all the inconvenient people cannot organize and raise resources enough to play legitimate politics and are often reduced to consorting with dubious characters or operate through unconventional channels.

Of course, the catch is this is how “democratic” politics works most of the time as well–seemingly much more than it used to. “Politics” is so “managed” that dissenters can’t organize and compete politically on level grounds.

I’ve always thought that the strength of democracy is not that politics does what “the people” want (I don’t think such a thing exists, even when you make totally unrealistic assumptions about how people think, as Arrow showed.) but because it provides for an internal self correction mechanism: if you (the government) are doing “bad things” and too many people are unhappy, the mechanism for forcing you to change is built into the system. But this works only if the politics is not managed “too well” and the dissenters can organize effectively and form a serious enough threat to the status quo. (It’s hardly a new argument: Lindblom said something similar decades ago–he called it “the intelligence of democracy,” iirc. )

If “our democracy ™” operates by shutting up dissenters and make it difficult for them to organize and, indeed, constitute a realistic threat to the status quo, such a “democracy” is very dumb indeed.

If you simply substitute the words “the 1%” every time you see the word “democracy”, these hand wringing articles make a great deal more sense.

Lets be fair it is the “0.1%” but point taken.

The paper as presented fails the first test of any analytical process in providing no definitions of the key terms which form the basis of what is passed off as ‘analysis’. Nor does it make explicit its core assumptions.

Setting out a definition of terms and making the a priori assumptions explicit was standard practice even at undergraduate level forty years ago.

Instead, the authors of this shoddy piece of work assume definitions of key concepts such as ‘misinformation’, ‘propaganda’, and ‘bias’ based entirely on definitions determined by a narrow self-interested elite focused around the WEF which represents a tiny minority of what is at best about one seventh of the world. Resulting in a process which pre-assumes what it aims to deduce. As does much of what passes for analysis across The Collective West in recent decades.

Citing a proven work of fictional disinformation in the form of the widely discredited “Russiagate” Official Narrative to shore up a biased narrative structured entirely around an obvious disinformation and propaganda laden “study” inadvertently qualifies this paper alongside the Sokal Hoax papers……

https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2018/10/new-sokal-hoax/572212/

….which clearly was not the intention of the authors.

A classic example of the concept of Gormlessness.