Yves here. Even though this post looks at the question of what to do about the baby bust in wealthy countries from an economic perspective, unlike many other accounts, it treats seriously the question of how to adapt to a static or falling population. It suggests investing heavily in citizens to make them more productive, particularly focusing on education. It also recommends improving health care and allowing for more flexible work arrangements for the aged, and of course includes the usual trope of better child care.

It’s noteworthy how many of these policies are at odds with the default behavior under neoliberalism, particularly turning schooling and medical care into looting opportunities.

By David Bloom, Michael Kuhn, and Klaus Prettner. Originally published at VoxEU<

Fertility rates have been declining in high-income countries for decades. This trend, along with increasing human longevity, poses a challenge for advanced economies. This column argues that a holistic set of policies can be implemented to address the economic risks. These policies should stimulate human capital accumulation and education, which are more important than population size for economic prosperity. Furthermore, polices should promote healthy aging and more choice over retirement decisions, and family-friendly policies to slow the fall in fertility should be enacted.

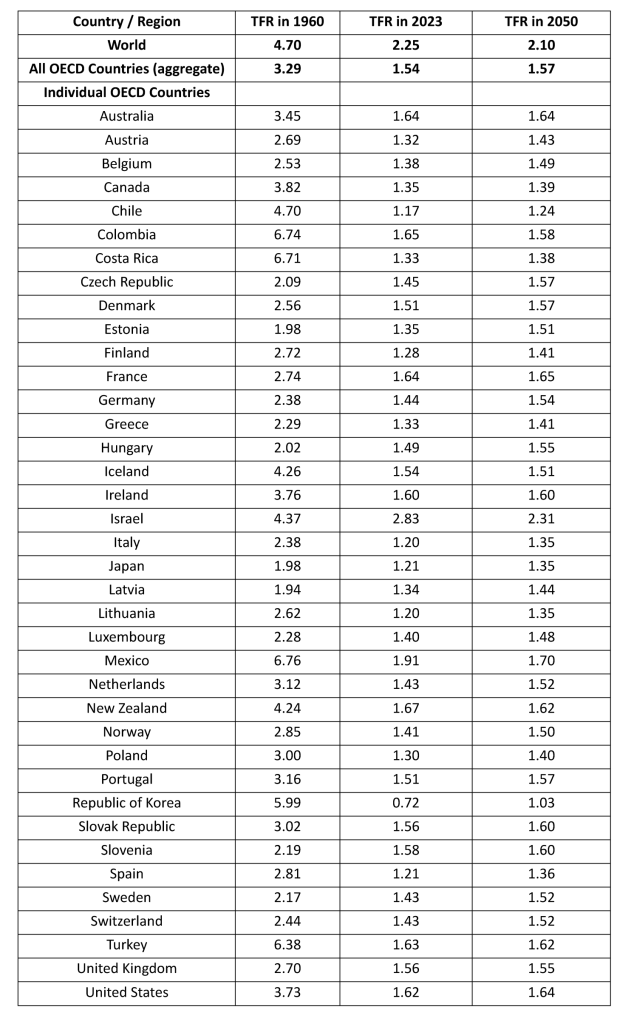

Fertility rates have been declining in high-income countries for decades. From 1960 to 2023, the total fertility rate (TFR, which represents the expected lifetime number of children per woman, given current age-specific fertility rates) among OECD countries fell by more than half – from 3.29 children per woman to 1.54 (United Nations 2024a). All but one of the 38 OECD countries (Israel being the exception) currently have a TFR well below the long-run replacement rate of roughly 2.1, meaning that their total and working-age populations are on long-term contractionary paths (see Table 1).

Table 1 Total fertility rates (TFRs) of OECD countries and the world in 1960, 2023, and 2050

Source: United Nations (2024a); see also United Nations (2024b) for a description of the TFR estimation and (medium scenario) projection methods.

In “The End of Economic Growth? Unintended Consequences of a Declining Population,” Charles Jones argues that the “profound implications” of low fertility include a growing paucity of new ideas that could effectively asphyxiate innovation and lead to long-run economic stagnation (Jones 2022). He points out that multiple economic growth models centre on innovation and that a larger population with larger absolute numbers of researchers, scientists, and inventors—and therefore, more bites at the (breakthrough) apple—is likely to achieve more (and more significant) discoveries. Jones proposes a model in which negative population growth leads to an ‘Empty Planet’ scenario (Bricker and Ibbitson 2019) wherein “knowledge and living standards stagnate for a population that gradually vanishes”. Jones juxtaposes this outcome against one of continued population growth and improvements in living standards that he calls the ‘Expanding Cosmos’ (Jones 2022). “Can the quality of people substitute for the quantity of people in the production of ideas?” Jones ponders in a Stanford Graduate School of Business piece. “Basically, the answer’s no. If the number of people is shrinking to zero, it’s hard to imagine that one person with lots of education can make up for a billion people that contain Einstein and Edison and Jennifer Doudna” (Gilson 2022). While Jones allows that automation and artificial intelligence could help maintain or improve living standards by propagating scientific advances, the central question of his piece’s title sounds an ominous note for declining fertility (Jones 2022).

In our recent paper (Bloom et al. 2024), we review data and ideas pertaining to the historically unprecedented fertility decline that characterises today’s wealthy industrial countries. We acknowledge that falling fertility could hinder innovation. But we argue that changes in behaviour, technology, policy, and institutions can influence the economic impacts of fertility and workforce decline and fertility levels themselves.

Innovation is indisputably a driver of economic progress, but it depends on more than just population size. Human capital – the skills and capacities that are embodied in people and enhance their ability to create valuable goods and services – is also key to innovation. Another basic feature of human capital is that it can be purposively accumulated, typically through investments in schooling, job training, or health.

Education, for example, is a well-established determinant of macroeconomic performance and economic well-being. It also tends to expand naturally under conditions of low fertility, leveraging wider and deeper investments into the knowledge and skills of small-sized cohorts. In this way, low fertility tends to enhance a population’s capacity for innovation and enables it to create more value through work, spurring both individual and societal well-being (Lee and Mason 2010, Prettner et al. 2013). Other things equal, small birth cohorts also aid population health.

History and rigorous research indicate that a population’s productive characteristics figure more prominently than its size in defining its capacity for knowledge creation and innovation. The number of healthy and well-educated people – which is distinct from the number of people – represents the human capital that rightly features in the knowledge production function as a fundamental determinant of technological progress and economic growth.

Oded Galor’s recent book, The Journey of Humanity: The Origins of Wealth and Inequality, buttresses our more optimistic perspective on the implications of low fertility for economic growth. This book centres on the argument that falling fertility and rising education (and subsequent technological progress) leading to human capital formation is at the core of long-term increases in economic prosperity (Galor 2022). Indeed, Galor points out that since the 19th century, life expectancy has doubled and per capita incomes have skyrocketed 14-fold across the globe, spurred by fertility decline that alleviated population pressure, paving the way for human capital accumulation and dramatic improvements in living standards.

Low and declining fertility also translates into short- and medium-term declines in youth dependency rates, which can further charge the economic growth process by naturally boosting rates of labour force participation, savings, and capital accumulation. This boost, which is known as a demographic dividend (Bloom et al. 2003), contributed up to 2–3 percentage points to the growth rates of income per capita in many countries following the end of the baby boom that occurred in the aftermath of WWII. As such, the trend of falling fertility in high-income countries from the 1950s to the present day has promoted – not impeded – economic activity and improved standards of living.

The challenge of low fertility is magnified by the fact that it causes older-age population shares to swell. Population aging may naturally hamper economic activity insofar as older people impose significant burdens associated with public expenditures on health and long-term care and economic security and tend to work less than their younger counterparts. Social and economic adaptations to these demographic realities are nevertheless possible.

Retirement policy reforms are one of those adaptations (Kuhn and Prettner 2023). Such reforms have considerable potential to forestall workforce shrinkage by removing the disincentives to working longer that increasingly long-lived people face. This strategy is emblematic of how policies related to declining fertility may be stronger in unison than in isolation: robust investments in the health and education of a relatively small youth and prime-age adult cohort may enable that cohort – as it reaches the older ages – to be healthy and well-trained enough to work productively past traditional retirement ages. In the middle of the United Nations’ Decade of Healthy Ageing, a frequently asked question remains relevant: are we just adding years to life, or are we also adding life to years (Bloom 2019)? Coupled with allowing more choice over retirement decisions, policies promoting healthy aging could relieve the mounting pressure on pension and health systems and the accelerating demand for long-term care in the wake of population aging (Bloom 2022). Thus, stakeholders would benefit from combining synergistic policy initiatives to augment their efficacy.

Public and private policymakers also have at their disposal a myriad of family-friendly policies that can slow or reverse the fall in fertility. These policies, which seek to balance work and family responsibilities, include tax breaks for larger families, extended parental leave policies, and—most effective of all, according to Doepke et al. (2023)—public and/or subsidised childcare. Of course, if such policies achieve their aims, the short- and medium-term result would be an increase in the youth dependency ratio, with gains in workforce size not beginning to accrue for approximately 20 years.

Policy decisions must be mindful of the evolving work landscape, particularly the rise of digitalisation, robotics, automation, and artificial intelligence (see Prettner and Bloom 2020). While these tools offer tantalising potential, such evolution will not only impact the types of jobs available and how they are performed (as well as what is produced and consumed), but it will also affect the way that workers interact socially, which will likely have significant implications for dating and partnering, with an as-yet indeterminate effect on fertility levels and patterns.

Thoughtful policy changes should be holistic, recognising the social and political repercussions alongside the economic outcomes. Policies that relax or restrict international migration may be nationally or internationally destabilising, depending on contextual factors, and have implications for social and economic equity. In addition, the environmental implications of low fertility must be kept in view as it could slow or accelerate the pace of climate change depending on whether fewer people with higher incomes have the net effect of easing or intensifying greenhouse gas emissions.

Low fertility and fertility decline are indisputable realities in high-income countries across the globe. Given the significant uncertainty surrounding the nature and magnitude of its attendant economic consequences, ignoring the low-fertility alarm bell would be imprudent, particularly when fertility decline is paired with another dominant demographic trend: increasing human longevity. But demography is not destiny. Fertility decline—and its implications for population size and structure—poses serious challenges, but they are not insurmountable. Humanity has an admirable record of identifying and taking advantage of the opportunities it faces. In this situation, multiple mechanisms are available for countering low fertility and addressing its economic repercussions. The time is ripe for mounting a swift and integrated response to pinpoint and implement the most promising policy countermeasures.

See original post for references

You would think that the west would take into account what’s mentioned above. Instead we have the deliberate crapification of both education and health systems as we all know on this forum. Though the above made me think that Malthusian economics need to be revisited, we need to reject notions that our retirement systems are set in stone and can’t be changed for the better despite population decline. The politicians spouting TINA, and that the only solution is to raise retirement age can go suck a hose.

Philip Pilkington’s article on the topic in links last week I think pointed out the impossible trilemma of population decline. But there is a ‘fourth’ possible way out, which is productivity. If you want to take an optimistic view, there is the potential to compensate for fewer younger workers with technology. We may, for example, be on the verge of a breakthrough in robotics, whereby a lot of low productivity labour (especially in agriculture and the service industry) could be done away with. But this of course only increases productivity if the displaced workers are upskilled, even if it is just as carers for the new wave of elderly, who hopefully won’t all have post covid early dementia.

Unfortunately, the countries on the front wave of demographic decline don’t provide a reason for optimism. Even a very well organised country like ROK has managed to combine reasonable economic growth and demographic decline with a very serious youth unemployment problem – and its not alone in this (in different respects, you can see the same features in low population growth countries such as Japan, Taiwan, China, much of eastern and southern Europe, etc). Its pretty clear that only a fundamental restructuring of labour markets and social protections in the broadest sense can allow for an equitable and controlled demographic decline. But as we know, that requires a level of foresight and competence that seems beyond our glorious leaders.

Human productivity seems to depend on leveraging energy.

A human driving an earth mover may be viewed as more productive than a human with a shovel, but the prior consumption of energy embedded in the earth mover and current energy consumption in running the earth mover arguably provides the increased “human productivity” observed.

If the hoped for increased “human” productivity results in ever more burned hydrocarbons, then we have added to another well described problem.

But the elephant in the room is the rapidly declining intelligence of the Western countries, most visible the US…any honest look at SAT scores, for example, will see that they have been declining since 1960, despite the SAT watering down the test and awarding bonus points to everyone…My analysis is that the decline is quite rapid, about 1 IQ point every 10-15 years….The basic problem is that smart people, especially smart women, aren’t having many kids, while the low IQ population is having more…Other causes are fluoride in the drinking water and multiple vaccines being administered before age 10…..

Interesting to me was the highest present fertility rate being in Israel. Affirms Alan Weisman’s book and findings (Countdown- excellent read). The only other above-2 (replacement) was Mexico. Musk and Trump should be opening that border and welcoming that Mexican and southern border invasion with open arms, as concerned as they are about not having a plebiscite workforce to wipe their bums and peel their grapes.

For me, the population decline is a good thing, a necessary thing, and we will see it get to 1 to 2 billions, and it will neither be pretty or fun for most of us. Heck , we make take it to near zero!

‘Interesting to me was the highest present fertility rate being in Israel.’

That needs to be broken down a bit. I believe that ultra-Orthodox have a birth rate over twice that of secular Israelis so is not a flat figure. I suppose the other countries’s figures may also have the same bias because of religion, class, wealth, location, etc.

Ultra orthodox are a special category, yes, but Israel actively promotes childbearing. Tel Aviv parks are filled with families of 2,3 young children. Noticeably different age range from, say, NYC parks.

How they promote, I’m not sure. Might be more propaganda than policy. But it is highly visible.

I think that ultra-orthodox families frequently have six or seven kids but if a secular family has only 2 kids, that is just ZPG.

As I recall, the ultra-orthodox, and the Gazans (is that Israel?) were the two fecund -as -mice cohorts.

Mexico’s fertility rate has been less than 2 children per woman for years. See here.

Interesting to me was the highest present fertility rate being in Israel- both present, and in 2050 (projected). Affirms Alan Weisman’s book and findings (Countdown- excellent read). The only other above-2 (replacement) was Mexico. Musk and Trump should be opening that border and welcoming that Mexican and southern border invasion with open arms, as concerned as they are about not having a plebiscite workforce to wipe their bums and peel their grapes.

For me, the population decline is a good thing, a necessary thing, and we will see it get to 1 to 2 billions, and it will neither be pretty nor fun for most of us. Heck, we make take it to near zero!

As to prioritizing health care , retirement, etc- that is simply a matter of political will, and political won’t.

The US has been and seems to trend as a staunch ‘won’t’. No Lives Matter.

No lives matter – Body Count

“Retirement policy reforms are one of those adaptations (Kuhn and Prettner 2023). Such reforms have considerable potential to forestall workforce shrinkage by removing the disincentives to working longer that increasingly long-lived people face.”

A polite way of saying: make people work longer in their lives, pushing retirement ages up.

Turn off the TY and Internet at 7 pm and discover the culprit driving low birth rates.

Maybe a little Al Green on the turntable.

It’s obvious that this earth needs a lot less people living on it. We just need to devise an economic system that functions without endless expansion. Seems like there’s unwinding to be done. Will our betters make an honest attempt to manage it, or will they collect their winnings and leave the table.

One possible, albeit minor solution to addressing population decline, and the lack of a sufficient labor force, would be to offer free education, at any level, and then in exchange, require the recipients to work in areas of need, at entry-level salaries. This has been done in the past, esp. in the medical fields, e.g., a nurse could work off school loans at say 20% a year for 5 years. Education is key to any society and economy, and the U.S. has made it excessively expensive. Its clear we need far fewer people on the planet, if the human experiment is to continue, and we need to address the changes in population now, not when its too late.

I read the article and could not find any mention of age discrimination, which is rampant in certain industries like tech. Education and on the job training sound nice in theory, but in practice employers prefer people who are ready to go from the get go or require very minimal training, which shifts the burden of education and its corresponding cost to potential employees, leaving less money and time for raising additional children?

Advocating for a higher birth rate when the job market is not at full employment due to age discrimination, etc is akin to another immigration policy, but this time from Wombworld and/or Netherworld.

Really good point. We need a significant cultural change to reduce age discrimination.

Why is the solution to every problem is more technology. Why can’t it be LESS technology.

It baffles me that if we trace the root of these problems we find is that it is the financialization and a purely capitalistic economy. So instead of saying “well maybe putting capital and economic growth as the goal is not such a good idea”, we use the same the mental frameworks that got us into this mess in the first place to get us out of it.

Exactly like what happened in 2008. What do you do when the bankers get us into a global recession? We put the same ones in charge to clean it up. And the result: a bigger mess.

Geez!

And surveillance opportunities.

The article does not consider the issues raised in other articles and in the comments here, that what is causing the shrinking TFR is a change in the distribution of fertility, I.e. those who have children in Western Society have as many as previous but many more people are childless. Unless the bimodal nature of fertility trends is accepted, the remedies are going to miss the mark. Why are people choosing to be or ending up being childless?

A study done by a Corey Bradshaw,a population biologist at the University of Adelaide in Australia, studies population ecology in animals. He looked at human population growth and discovered Population Momentum. Basicly it would take generation to slow growth enough to have any impact on lowering the human impact on the climate.

https://www.science.org/content/article/no-way-stop-human-population-growth

From the article:

The business-as-usual model matched U.N. projections of 12 billion people by 2100, giving the researchers confidence in their model. But they also saw booming population growth even when they introduced global catastrophic deaths of up to 5% of the population, the same seen in World War I, World War II, and the Spanish flu. When the computer model population lost half a billion people, the total population was still 9.9 to 10.4 billion people by 2100, the team reports online today in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. “It actually had very little effect on the trajectory of the human population,” Bradshaw says.

Not good news if the model is correct. Paper and article from 2014.

Link to the paper: https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.1410465111

Anyone with a good understanding of runaway climate change and the rest of the Overshoot predicaments, would have to be a sadist and a masochist to bring children into this world.

**Society will collapse by 2040 due to catastrophic food shortages, says study**

‘The results show that based on plausible climate trends and a total failure to change course, the global food supply system would face catastrophic losses, and an unprecedented epidemic of food riots’

https://www.independent.co.uk/climate-change/news/society-will-collapse-by-2040-due-to-catastrophic-food-shortages-says-study-10336406.html

I didn’t read beyond the title so maybe I’m out of line, but I have to ask… are low fertility rates a problem? There’s already way too many of us. Unless you have a problem of more brown people than white I say bring it on, more room for immigrants, maybe human rights will actually be respected… there’s all kinds of plusses