By Lambert Strether of Corrente

Since we seem to be in an apocalyptic mode just now, here are some headlines from last week:

Fireflies are fading from Maine’s night skies Portland Press-Herald

The number of monarch butterflies and other Wisconsin pollinators are falling. Here’s why Wisconsin Farmer

Where have all the wasps gone? BBC

But does this add up to an apocalypse? An extinction-level event? Some urge caution (from the early 2020’s: “nuanced“, “more complicated than thought“, “not so fast“). But since an insect apocalypse is a “risk of ruin” event, I think it makes sense to view it through a precautionary lens. In this post, I’ll do a quick survey of the literature, look at the weaknesses of the field, and then the causes and effects of insect “decline” (if “apocalypse” is too much; but regardless, on either a geological or even a history timescale, apocalypse is what we’re looking at, quarterly results aside).

Now let’s turn to the literature (PNAS has a fine history here). First, some country studies. From ITV, the UK, “Dramatic decline in insect populations over last 50 years, Sussex study finds”:

A survey of farmland in Sussex, carried out for more than 50 years, has seen a dramatic decline in insect populations.

The study tests the number of different insects present on cereal crops which overall has revealed that numbers have dropped by 37%.

It is done by using a vacuum backpack to sample the insects living amongst the cereal.

From the Sierra Club, the United States, “Study Shows Western Monarchs Have Dropped 97% in 35 Years“:

There’s been a lot of handwringing about monarch butterflies (Danaus plexippus) in the eastern United States, where the population of the migratory insects has declined from an estimated 1 billion insects in 1996 to about 100 million last year. The charismatic orange and black butterflies are iconic in part because of their epic 2,000-plus mile journey to a single overwintering spot in Mexico’s Sierra Madre Mountains. But a new study shows that the other major population of monarchs, which live in the western United States and overwinter on the California Coast, is suffering even steeper declines than its eastern siblings.

The study, published in the journal Biological Conservation, shows that in the last 35 years, the population of western monarchs has plummeted from about 10 million living along the west coast to approximately 300,000. Even more concerning, if present trends continue, the study indicates the western population faces a 72 percent extinction probability over 20 years and an 86 percent risk over the next 50 years.

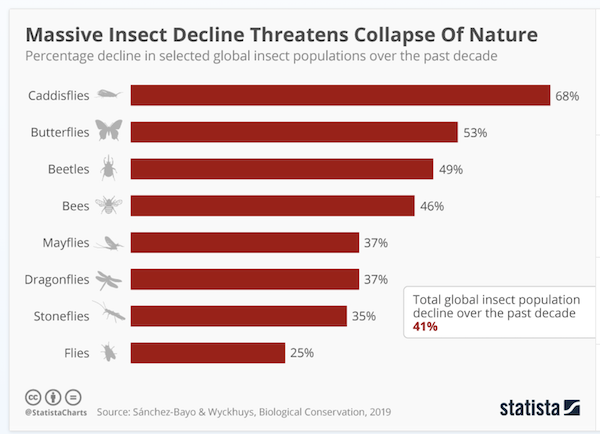

Monarchs are a single charismatic species — charismatic species, like polar bears or pandas, get disproportionate amounts of attention. And funding — but there are more insect species in trouble. From Statista, “Massive Insect Decline Threatens Collapse Of Nature” (2019), a handy chart:

Granted, dragonflies and (honey) bees are still pretty charismatic, but here is a review of the literature, “Insect population faces ‘catastrophic’ collapse: Sydney research” (2019):

A research review into the decline of insect populations has revealed a catastrophic threat exists to 40 percent of species over the next 100 years, with butterflies, moths, dragonflies, bees, ants and dung beetles most at risk…. “As insects comprise about two thirds of all terrestrial species on Earth, the trends confirm that the sixth major extinction event is profoundly impacting life forms on our planet,” write Dr Sanchez-Bayo and co-author Dr Kris Wyckhuys from the University of Queensland and the Institute of Plant Protection, China Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Beijing. Their study was published this week in Biological Conservation. It involved a comprehensive review of 73 historical reports of insect declines from across the globe, systematically assessing the underlying drivers of the population declines.

“Because insects constitute the world’s most abundant animal group and provide critical services within ecosystems, such an event cannot be ignored and should prompt decisive action to avert a catastrophic collapse of nature’s ecosystems,” the report said.

Another. From PNAS, “Insect decline in the Anthropocene: Death by a thousand cuts” (2021):

While there is much variation—across time, space, and taxonomic lineage—reported rates of annual decline in abundance frequently fall around 1 to 2% (e.g., refs. 12, 13, 17, 18, 30, and 31). Because these rates, based on abundance, are likely reflective of those for insect biomass [see Hallmann et al. (26)], there is ample cause for concern (i.e., that some terrestrial regions are experiencing faunal subtractions of 10% or more of their insects per decade).

That’s a lot. Some also find the speed of the decline alarming. From LeMonde, “Neither the magnitude nor the speed of the collapse of insects were anticipated by scientists” (2023)

Neither the magnitude, nor the speed, nor the systemic nature of the collapse of insects were anticipated by scientists. They are now measuring, stunned, the irreversible damage already committed.

In 2017, upon publication of the famous study by the Krefeld Entomological Society estimating at around 80% the drop in biomass of flying insects in some 60 German protected areas since the early 1990s, biologist Bernard Vaissière (INRAE), a specialist in wild bees, said to Le Monde: ‘If I had been told that 10 years ago, I wouldn’t have believed it at all.’ The other estimates that are accumulating and which largely corroborate this figure, still cause a sort of stupor among many specialists.

To be fair, insect decline studies all tend to have the same sort of weaknesses. For example, most insects have not been classified. Nor is there agreement on the numbers generally. From Friends of the Earth, “Insect Atlas“:

Compared to plants, mammals, birds and fish, insects are little researched. Only a small fraction has even been classified. Particularly little research has been done on the long-term occurrence and population dynamics of insects outside Europe and the US. Scientists agree that several well-studied species, such as monarch butterflies, some groups of moths and butterflies, and some species of bees and beetles are in decline – especially in Western Europe and North America. There is also consensus that insect biodiversity is decreasing in many parts of the world, while the numbers and biomass of the animals vary greatly depending on the region, climate change and land use, as well as the adaptability of each species. There is no scientifically confirmed figure for the global decline in insects. A first review by the University of Sydney in 2018 compiled information from research studies in various regions. It found that the populations of 41 percent of species are in decline, and one-third of all insect species are threatened by extinction. While cautioning that the available evidence is relatively thin, the researchers estimated that total insect biomass is declining by 2.5 percent a year.

Further, most studies are geographically limited (though not the reviews). From PNAS once more:

An important limitation of assessments based on long-term monitoring data are that they come from locations that have remained largely intact for the duration of the study and do not directly reflect population losses caused by the degradation or elimination of a specific monitoring site (although effects can be measured in a metapopulation context if the number of years sampled is sufficient in remaining sites). For example, butterfly censusing sites that have been lost to agriculture, urban development, or exotic plant invasions would not meet inclusion criteria for a study aimed at calculating long-term rates of decline. Surely, the greatest threat of the Anthropocene is exactly this: the incremental loss of populations due to human activities. Such subtractions commonly go uncounted in multidecadal studies

Finally, the field itself seems not to have the manpower to take on the job of measuring insect design (let alone teasing out causality). From the National Wildlife Federation, “Are Entomologists as Endangered as the Insects They Study?” (2024):

Scientists who identify, classify and study insects and the ecosystems they inhabit are essential to preventing the loss of the insect species that humans and all other living things depend on. They are also of critical importance for detecting and controlling diseases carried by ticks, mosquitoes and other invertebrates that can bring humans and other animals harm…. But Droege and other insect taxonomists like him are in short supply, especially when compared to the escalating need and the number of species still unknown to science…. Dwindling funds have fueled the taxonomist shortage. Over the past few decades, research funders like the National Science Foundation (NSF) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) have shifted their priorities from “old-fashioned” descriptive sciences like taxonomy to cutting-edge fields like molecular biology, with researchers and students adjusting their career trajectories accordingly. And as an older generation of classically trained natural historians approaches retirement, their slots at universities are remaining unfilled. ‘We’re rapidly losing the expertise we need in quite a diversity of areas,” says Lynn Kimsey, professor of entomology and director of the Bohart Museum of Entomology at the University of California, Davis. ‘The driving force in universities is funding, and almost all the funding out of agencies like NSF and NIH is directed at DNA.’ Her own department offers one example. “At one point we had three taxonomists: one working on ants, one working on spiders and one working on stinging wasps,” she says. “Within five years, two of the three will be gone, and they won’t be replaced. And I’m seeing that at universities across the country.”

So not only are the studies we have underpowered with respect to the scale of the problem, we might not even have the scientific capacity to do better.[2]

Perhaps, in the end, the best proof is bugsplat — or lack thereof. BBC, “Bug splat survey shows decline in insect numbers“:

Since the first reference survey in 2004, an analysis of records from nearly 26,500 journeys across the UK shows a continuing decrease in bug splats.

The number in 2023 saw a 78% drop nationwide.

(Wikipedia, more gracefully, titles its page on this topic “Windshield Phenomenon.”) A bugsplat sample seems to me to be just as sound a method as the “vacuum backpack” used to sample Sussex insects, in the first study I cited. So by that measure, insect decline is significant.

Most agree on the causes of insect decline. Science Daily, “The reasons why insect numbers are decreasing” (2023) summarizes the consensus view[2]:

Together with forest entomologist Professor Martin Gossner of the Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research (WSL) and biologist Dr. Nadja Simons of TU Darmstadt, [Dr. Florian Menzel from the Institute of Organismic and Molecular Evolution at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz] contacted international researchers in order to collate the information they could provide on insect declines and to stimulate new studies on the subject.

“In view of the results available to us, we learned that not just land-use intensification, global warming, and the escalating dispersal of invasive species are the main drivers of the global disappearance of insects, but also that these drivers interact with each other,” added Menzel. For example, ecosystems deteriorated by humans are more susceptible to climate change and so are their insect communities. Added to this, invasive species can establish easier in habitats damaged by human land-use and displace the native species.

Most also agree on the effects of insect decline. There’s a good deal of attention paid to pollinators. From CNN, “Parts of the world are heading toward an insect apocalypse, study suggests” (2022):

“Three quarters of our crops depend on insect pollinators,” Dave Goulson, a professor of biology at the University of Sussex in the UK, previously told CNN. “Crops will begin to fail. We won’t have things like strawberries.

“We can’t feed 7.5 billion people without insects.”

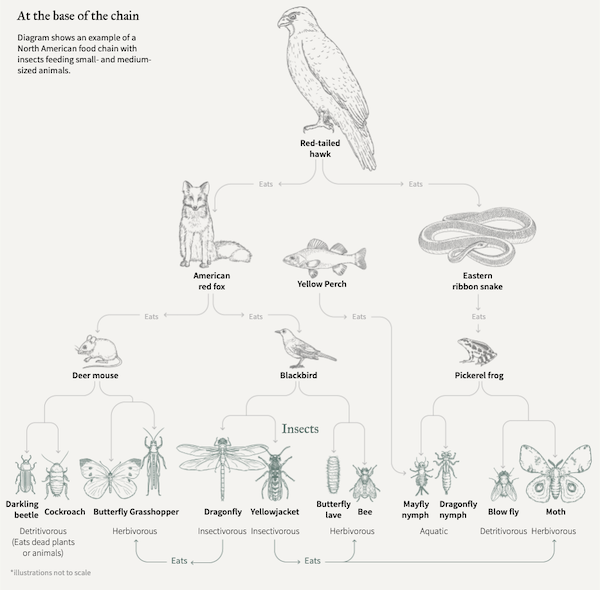

However, I think food chain issues generally could be even more important. From Reuters, “The collapse of insects” (2022) provides this handy diagram:

What happens when the species at the bottom of the food chain collapse out from under the species at the top?

The World Economic Forum published this opinion: “5 reasons why eating insects could reduce climate change” (2022):

We’ve been conditioned to think of animals and plants as our primary sources of proteins, namely meat, dairy and eggs or tofu, beans and nuts, but there’s an unsung category of sustainable and nutritious protein that has yet to widely catch on: insects.

Before you say “yuck,” hear us out.

(NPR, in its debunking of the idea that “The ruling class really, really wants us to eat bugs” omits it, oddly.) It would be amusing of this idea failed because there were no bugs to eat.

But what to do? From Princeton University Press, “Insect apocalypse” (2023):

Some solutions are obvious. Ban the worst of the insect poisons and limit the use of others. Unfortunately, most of these are manufactured by just a few giant companies who, through their immense wealth, have the ear of politicians and lawmakers. We also need to de-intensify farming to create space for insects along with other animals and plants. This could be achieved through reshaping farming subsidies, but this too is painfully slow to filter into the minds of political leaders.

And then, of course, climate change. But we can also consider helping the insects by land use changes, not such a heavy lift. From Nature, “Agriculture and climate change are reshaping insect biodiversity worldwide” (2022):

A high availability of nearby natural habitat often mitigates reductions in insect abundance and richness associated with agricultural land use and substantial climate warming but only in low-intensity agricultural systems. In such systems, in which high levels (75% cover) of natural habitat are available, abundance and richness were reduced by 7% and 5%, respectively, compared with reductions of 63% and 61% in places where less natural habitat is present (25% cover). Our results show that insect biodiversity will probably benefit from mitigating climate change, preserving natural habitat within landscapes and reducing the intensity of agriculture.

We can also help the insects by, as it were, brightening the corners where they are. From EurekAlert, “Monarch butterflies need help, and a little bit of milkweed goes a long way“:

Research shows that planting milkweed in home gardens can add significant monarch habitat to the landscape. In a new study in the journal Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, researchers and community scientists monitored urban milkweed plants for butterfly eggs to learn what makes these city gardens more hospitable to monarchs. They found that even tiny city gardens attracted monarchs and became a home to caterpillars.

(Alert reader sc is a milkweed maven; see here.) And of course it’s always possible to plant flowers:

At the beginning of June, we planted sunflowers and a strip of annuals in the top field at #YewView. It’s looking mighty lovely today and the most insects I’ve seen in one place, this summer! pic.twitter.com/fwPlrJEebh

— WildlifeKate (@katemacrae) August 5, 2024

I know all these efforts are small, individual efforts. But if we think of climate change as a great fire, we can see that some of the seeds that we, as individuals, plant will survive and grow when we are through the evolutionary chokepoint and the fire has burnt itself out (albeit in a different world from the one we now live in).

For a coming post, I’ll see if there are more muscular and systemic efforts that can be taken (for example, classifying some insects as endangered species; curbing insecticide use at the municipal level; getting HOAs to surrender their lawn fetish). However, we (for some definition of “we”) would have to act quickly and from partial knowledge. But for now, we can do lots of these small things.

NOTES

[1] The same seems to be true of medical entomologists. Recently, a Japanese scientists discovered an insect vector for H5N1 (the blowfly). It would be a shame of we lost that capability.

[2] There are also particular causes within these general causes, like the effect of climate on insect digestive systems and phenology (the timing of various larval stages and emergence of flying adults, dams, and streetlights making leaves tougher. Also, generalists (cockroaches) tend to thrive, and specialists (monarch butterflies) not.

Where have all the wasps gone?- BBC

My parents’ backyard patio.

I just came to say, “To our backyard” !! Rick got stung yesterday 5 times. He’s swollen up like a bad drawing.

We lost our paper wasps mid spring 2020. They just up and disappeared.

Thanks for this post. Lots of good reading.

Wasp remedies (including plants). I have not tried, but maybe some readers have:

EXCELLENT!! Thanks, we will experiment with some of these.

But of course, if we want to avoid a Waspocalypse, we will make sure to plant some wasp-support plants in some places.

I see many kinds of wasps at my goldenrod and fennel blossoms. I see more specifically honeybees in particular at my sedum blossoms.

For several years before the huge polar vortex superfreeze in the midwest, I had a fair number of the big wing-flicking blue-black mud-daubers at my fennel flowers. I also had a wasp whose name I didn’t know. It was even bigger than the mud-daubers . . . sort of between a mud-dauber and a paper-wasp in shape and in color a pattern of muted yellows and browns.

Starting with the spring after that polar vortex winter, those even-bigger wasps disappeared and have not yet reappeared. After a few years, the mud daubers have returned in numbers much smaller than before the polar vortex superfreeze.

And in general, I see a lot less paper wasps everywhere and anywhere.

Eat ze bugs. / ;)

and be happy

https://odysee.com/@Chilledcommunications:2/Klaus-Schwab-Own-Nothing-Be-Happy:a

Swallows eat bugs no? Bumper season for swallows in our area (Greece, Eastern Peloponnese). The chicks all grew up and they flew off to greener pastures just yesterday.

Bumper season for swallows in our area (Greece, Eastern Peloponnese).

I was just yesterday mentioning to my spouse that the swallows that annually set up shop in our vicinity [a marina in southern Denmark] just aren’t here this year.

Ours in Northern California redwood country are in long-term decline, but this year they look pretty good. A couple of recent years they had fewer and sicklier chicks, though we still have plenty of bugs.

Hmmmm, I can only offer anecdotal evidence, but insects abound in our neck of agricultural Western Massachusetts; and that despite copious amounts of herbicide and insecticide dumped on Connecticut River bottom land crops directly adjacent to our unsprayed orchard. Banner firefly year, dragonflies everywhere, clouds of gnats whilst riding the bike at night. Dung beetles, moths, butterflies cruising. Swallows and Redtails swooping at the airborne feast. I’m honestly not sure what to make of this contrast, but suspect it has to do with relatively intact ecosystems vs more developed / barren areas?

> insects abound in our neck of agricultural Western Massachusetts

Decline does vary and would be interesting to know why. Not to assign work, but the next time you look at the fields, could you check the land use? As here, above:

Perhaps there are strips along the fields where insects (and birds) can congregate?

theses folks would love to work with anyone interested:

https://www.xerces.org/

just a thought

That looks like a really good resource (there’s so much good stuff online, it’s really odd we can’t find it). Anyhow, I just signed up for their newsletter (along with every other newsletter in the world…).

I remember when Al Gore was talking dreamily hopefully of the Information Superhighway to come.

I remember thinking that “Business” would turn it into the Infommercial Supersewer as fast and as totally as they could figure out how to do that.

I don’t think it is odd at all that we can’t find the good stuff which is online. I think that is one of the basic purposes of the search prevention engines as they have been refined to exist now. Perhaps one could call them search perversion engines. They and the Advertising Industrial Complex they co-form a happy helix with have co-optimised the search prevention and perversion engines to wear out and frustrate the would-be searcher into giving up before ever finding any hint of the good stuff online.

At some point one has to accept the fact that this is what search engines exist to do now . . . prevent people from ever finding the good stuff online. One has to resign oneself to the basic reality that search engines have to be treated as Russian or North Korean minefields-in-depth which the searcher has to thread his way through, around, over, under, etc.

So people who want to find “good stuff” will have to invent “other ways” to find it. If you have an exact name in your memory, you can type that in and you might get the online version of what you want. I can type in ” Xerces Society” and I will find “Xerces Society”. But I can’t do that if I don’t know or remember the name “Xerces Society” to begin with.

Since I remember the name ” Pollinator Nation” from some years ago, I can still find it by typing in the words ” Pollinator Nation”. Typing in that exact name got me two interesting sites . . .

https://www.thepollennation.com/

and especially the non-business

https://pollinator.org/

There is still a way to sneak up on links to good stuff online from the side even if you don’t know the name of any particular good link in the general area you would like to find good links to. And that is to type in the word or words for finding a bunch of pictures of the particular subject you would like to see if any good stuff exists online about.

For example, do you think that “insect pollinator” might be a subject with some possible good stuff online about them? Type in ” insect pollinator image” and get . . .

https://images.search.yahoo.com/search/images;_ylt=AwrE_WwKgrJmRLkmJqRXNyoA;_ylu=Y29sbwNiZjEEcG9zAzEEdnRpZAMEc2VjA3Nj?p=insect+pollinator+images&fr=sfp

Look at every image’s url. Most of them will be one of a few multi-photo dumpsites, but one might get lucky and find an interesting url to a goodstuff site online, which one would never find otherwise without knowing its specific name or url.

Or , for example, ” wild desert potato relative image” led me to . . .

https://images.search.yahoo.com/search/images;_ylt=AwrFaIxbg7Jmp2MqLnlXNyoA;_ylu=Y29sbwNiZjEEcG9zAzEEdnRpZAMEc2VjA3Nj?p=wild+desert+potato+relative+image&fr=sfp

and one of the pictures that gave me had this url . . .

https://www.cultivariable.com/catalog/potato/potato-wild-relatives/

which seems like a good stuff online site to me.

( Of course people with the skill to beat this directly out of a “search” engine won’t need roundabout methods like this . . . if such skills still work for those who have them).

Living in brazilian countryside, during the last 30 years, four times a year, I have travelled 600 Km from my city in the interior of Minas Gerais to São Paulo (The largest brazilian city).

I have given little thought to it, until now, but after read the passage in the text about bug splat, I am amazed.

I remember, in the early 2000, I frequently had to clean the windshields.

At some point in the last years, I did not need that anymore.

Last travel, in july, 2024, during the travels, the windshield was not hit by any bug, zero, nil, 0.

On a 6 day 3000 mile cross country trip in the USA this past June, I washed copious bug guts off the car every day

I drive around Tennessee, Mississippi, and Alabama visiting family. A few years ago, it seemed like bug population had fallen. Not many bugs on the car. Last couple years, lots of bugs, like when I was kid in the 80’s

Myself and others in northern California have noticed the same thing.

A fear I have had is that they are a bad indicator like when ocean ecosystems collapse but there are blooms of squid. I do not know the species on my windscreen now nor what they used to be.

Cross country drive and bugs. Most years we drive from Oregon to western Minnesota, sometimes to the Twin Cities. Driving US 12 through South Dakota takes us through Standing Rock Indian Reservation. The healthy presence of bugs is immediately noticed compared to all other areas. No surprise to me.

It seemed as if maybe 10% of cars/trucks had plastic bug deflector screens on the front of their hoods in the 1980’s-90’s, but you hardly see them anymore…

For the first time in maybe 5 years, I garnered enough dead insects on my windshield to force me to pull into a gas station on Hwy 395 in order to squeegee them off, as my view was compromised.

For 25 years we have driven from Central Texas to Northern Minnesota to summer at our cabin. About 5 years ago we noticed a drastic reduction in bugs. We used to have to wash disgusting amounts of bug guts off our windshield at least three or four times during our drives, especially as we entered Kansas going north. This year we washed a light amount of bug guts off in Oklahoma and then in South Dakota. Currently dragon flies are light and we have only seen a very few butterflies this summer. Flies are pretty sparse so far also.

So we spray poisons all over the world and yet we haven’t reduced the mosquito population?

Used to be that driving the blue highways in our state would yield a bug plastered windshield. Not anymore. No doubt all the field spraying has killed them off. There are a lot of bees here. We don’t have turf grass, mainly just native ground cover. Monarchs used to fly in a path through our yard. It has been a few years since we’ve seen them.

I wonder what, if any, role the ubiquitous soakdown of everything everywhere by cell-phone-tower radiation is having on all the insects who have to experience that radiation filling up their habitation volume 24/7 without a second of relief.

Add that on top of the constant marination of whole ecosystems in pesticide fallout, especially the superdeadly neo-nicotinoids which are super-focused on destroying insect brain function, and one begins to wonder how much the different pressures force-multiply eachother in forcing insect populations downward.

> cell-phone-tower radiation

In my survey of the literature (and I did read a significant chunk of the review studies) this never came up.

What would cause me not to regard this suggestion as woo woo would be a study of insects from an entomologist in a decent source (i.e., not Natural News or anything of that ilk) that suggests a mechanism for how the effect works.

I repeat, “study of insects,” not of humans, not “radiation bad” etc. etc.

It would be hard to get any studies at all given the shortage of entomologists today and tomorrow. One suspects that the few entomologists in existence are/will be kept busy studying the immediate or pressure of certain insects on food and fiber production.

The first few studies would have to be about whether such EM radiation actually does have an effect on insects within its reach. If studies determine it actually does, then more studies would have to be designed to see what, how and why that effect is in order to permit the suggestion of a mechanism.

One wonders if there are any large zones without CellTower/WIFI radiation which could be compared to eco-similar zones with CellTower/WIFI radiation. For example, parts of the rainforest in NorthernMost Australia are eco-similar to immediately “adjacent” parts of the New Guinea rainforest. They even share some species ( black cockatoos, cassowaries, etc.). If there is an EM radiation soakdown-zone of rainforest in Australia and an eco-equivalent zone of EM radiation-free rainforest in nearby New Guinea, then perhaps the insect numbers in those two places could be compared. If no difference then maybe no problem. If difference, then why?

The Clash always makes my day. But the world-class, bespoke scum-bags known as private equity are displaying increasing signs of serious illness. Easing into the schadenfreude; increased interest rates (no more free money) has led the “industry” to experience more and more sick-days.

The carrying costs of their stripped down and debt-laden casts of businesses are becoming burdensome. Typically they can off a business on the unwary investment stiffs in under five years. Not so anymore. They can’t get the numbers, so they have to keep them on the books. But they gotta finance them…costly.

They have been using net asset valuation to attempt to get loans to keep the wrecks afloat until the market turns. Lenders are hip to this scam and take their football and go home from a field that may or may not be 100 yards in length. Bummer.

So, they create “continuation funds” whereby their various dreck are shuffled into new funds and relabled to keep up the grift. This is explained by the best student in Economics class: Stringer Bell…(start at 1:55).

All the while the limited partners want to see their cash flow and the general partners are forced into continued borrowing…pass the popcorn.

We’re cutting off our legs to fill our wallets. Not real clever.

Well . . . ” we” aren’t.

“Them” are cutting off “us’s” legs to fill ” them’s” wallets. Not real nice.

Making leaves tougher is only one of the problems that insects face when living under artificial lights at night (ALAN):

The switch from high pressure sodium street lighting to LED street lighting has made things worse:

Street lighting has detrimental impacts on local insect populations

I forgot to add, to see how bad the problem of light pollution is, ClearDarkSky’s Light Pollution Map is an excellent reference.

(Off-topic, but one interesting thing to note on this map is the massive light pollution generated by the oil industry drilling in the Bakken shale formation in sparsely populated western North Dakota).

Risking Lambert’s wrath, here is a shameless plug for one of my favorite small businesses. They are up in Cincinnati, so no personal connection with them; I have just been a customer of theirs. This is a really good resource for anyone interested in creating a habitat of their own.

https://lovenativeplants.com/?ss_source=sscampaigns&ss_campaign_id=66ae33c2bfeb326c73884196&ss_email_id=66ae3a3a0574606425b8ef27&ss_campaign_name=+Native+Seed+Mix+Species+Lists+%2B+Articles&ss_campaign_sent_date=2024-08-03T14%3A10%3A15Z

Thanks for this link, where I learned that spiderwort, the scourge of my garden, is edible! Although I’ll still try to get rid of it because it’s wildly invasive and nothing else stands a chance against it, I know I’ll never succeed. But while I’m failing, I can at least throw a few of the gorgeous purple blossoms on my salad, as long as I’m eating salad before about noon. The blooms close up tight in the midday sun, only to reappear the next morning. I will taste the leaves when I go outside later, but they don’t look very appealing as a salad green.

Here’s another edible weed that gallops all over my garden:

https://www.almanac.com/purslane-health-benefits-and-recipes

I particularly like it cooked up with lentils in a spicy Indian dal. Very good, and apparently good-as-heck for yah!

If it is merely “edible”, then that doesn’t help all that much. If it is really “good”, or if you can find a way to make it really “good”, then you may start eating so much of it that “invasiveness” stops being an issue.

I munch Purslane raw and in salads

It is also great pickled.

House fly once seen every where has dramatically dropped in numbers. Mosquito seems to be doing just fine

Thank you for publicizing this very important aspect of ecosystem collapse. The PNAS article referenced several times contains a link to an Entomological Society of America symposium which explored “insectageddon” in some depth. The talk by Dan Janzen and Winnie Halwachs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6uHlIHaNrS0 is especially interesting since it comes from a tropical point of view (Costa Rica) and has some vivid graphics of insect decline in a popular ecotourism destination.

As an insect taxonomist myself, I totally relate to the paragraph on endangered entomologists. However, we’ve been singing the same dirge for the last 40 years, to little avail. And, much as I like the small scraps of support that have been thrown our way, if I’m honest, I have to admit that more research and endless studies are not what is now needed to address Insectageddon. As Dan Janzen has said, “The house is burning. We do not need a thermometer. We need afire hose.”

The “official science” has notably failed to come up with an answer as to the cause.

Electromagnetic pollution caused by cell phones & WIFI is the only explanation that fits with the timeline of the collapse.

I wonder what the timeline of the introduction and rollout of specifically the neonicotinoid insecticides is. If it is roughly similar to or even more recently starting than the rollout of Electrosmog Everywhere, then could neonics and electrosmog force-multiply eachothers’ bad effects on insects?

If there are huge enough areas without electrosmog generators that no electrosmog can reach into these areas from the sides, could those areas be studied for insect amounts? And compared to similar areas with electrosmog?

And if it were proved that electrosmog from cellphones and WIFI and etc. is wiping out the insects ( and then everything else above them on the food chain in due time), would the legions of cellphoners and WIFI-ists give up cellphoning and WIFI-ing? Or would they decide a world without insect life is worth it to keep cellphoning and WIFI-ing? Or would the merchants of celllphone and WIFI “flood the zone” with bullFUD designed to keep the knowledge from reaching the massbrains of the massmind to begin with?

I’m afraid the telecom-industry incl the military-complex are in charge influencing politicians about the negative economic impacts involving stopping or slowing the business expansion of the digital economy. Security and health will be put secondhand.

> The “official science” has notably failed to come up with an answer as to the cause.

Do consider reading the post. It explains the several causes (not “the” cause), and also explains the limitations of ‘”official science”‘, especially into terms of the number of scientists. As readers know, I am a big fan of citizen science, but I assume that since if there were decent citizen science on this, you would be citing to it. Therefore, there isn’t, and we are left with handwaving and woo woo.

> Electromagnetic pollution caused by cell phones & WIFI is the only explanation that fits with the timeline of the collapse.

See here. Make a claim like that, back it up with evidence, champ. This isn’t a chat board.

I’m surpriced the studies don’t mention electromagnetic fields! Radiotransmission using cellphones/basestations/satellites have dramatically grown in use over the earth. How about the sun and the long term falling of the number of sunspots making the earth succeptible to more cosmic rays (magnetic shield weaker)?

Studies in Canada have shown a dramatic reduction of honeyebees when using 4G radiation compared to a non radiated area. (Sorry I don’t have the source).

> I’m surpriced the studies don’t mention electromagnetic fields!

See here for how to make this claim into something other than woo woo. You don’t have a source? Go find it.

Sorry Lambert,

At the moment I could not find the referenced (recent) study from Canada. Here is an article

( link ) from 2017 giving you some important sources.

https://ehtrust.org/published-research-adverse-effect-wireless-technology-electromagnetic-radiation-bees/

When I started riding a motorcycle back in the 1990s, a few hour’s ride would leave me covered in dead flies, almost unable to see through the visor.

Now I work as a courier, 50 hours a week on the road. So far this year I have had to clean one (1) bug splat from my visor.

The apocalypse has already happened.

France has recently prohibited any trimming of trees or hedgerows by farmers from April-September and cutting/trimming is “strongly discouraged” for private gardens as well. This is on top of a general prohibition on tearing out hedges that’s been in place since the early 2000s. It’s estimated that 70% of the hedgerows that existed in 1950 are now gone, and with them, birds and small mammal hedge dwellers that fed on insects. An entire ecosystem that cooperated in food production for a thousand years.

I was very worried about the butterfly and bee population in my area until about a week ago when they suddenly showed up. It was due to an unseasonably wet and cool summer. As you might have seen in the Paris 2024 Opening Ceremony lol.

re: hedgerows. Glad the French wised up and now prohibit destruction of hedgerows. UK has similar restrictions. Touring the UK decades ago I was struck by the age of some of the hedgerows and how it framed rural roads I crossed while hiking ley lines.

A Heartland nonprofit has received funding from USDA to install hedgerows. USDA says they promote the establishment of hedgerows for the following reasons:

• Provide habitat including food, cover, shelter or habitat connectivity for terrestrial or aquatic wildlife.

• Provide cover for beneficial invertebrates as a component of pest management.

• Filter, intercept, or adsorb airborne particulate matter, chemical drift, or odors

I always thought the US Interstate highway system provided ample space on the edges for establishing native plantings for pollinators and wildlife. While it would filter dirt and some noise, it would likely increase both roadkill and bugsplat.

I live in a rural area in New Hampshire. The landscape is mostly woods and fields. I have tons of flowers in my yard and tons of bugs. Bees, butterflies, moths, beetles and of course mosquitos.

At the local garden shop last week the monarchs were all over the place. Bought a day lily and as I put it in the car discovered a bright green frog hitching a ride.

just lost a long comment so i’m making this short:

central tuscany, isolated property at 600 meters surrounded by woods. little light pollution. no pesticides in greater area. shocking reduction of insect population. this year only three varieties of butterflies where we once had so many. our old faithful zebra swallowtail is down to two couples. beetles as well. as beekeepers we have great deal of lavender and other flowering plants, no competition since no nearby neighbors.

tuscan honey production is way down, professionals struggling to stay in business. ours is down but we’re not dependent on it.

fewer wonderful swallows and swifts.

have yet to get a mosquito bite inside or outside the house.

Sorry Lambert,

At the moment I could not find the referenced (recent) study from Canada. Here is an article

( link ) from 2017 giving you some important sources.

https://ehtrust.org/published-research-adverse-effect-wireless-technology-electromagnetic-radiation-bees/

Herbicides like Bayer/Monsanto Roundup destroys important amino-acids (3 types) in the soil. These three amino-acids are essential for the life in different plants. Amino-acids are i.e the basic stuff in the production of protein, a necessety in humans, insects or plants.

https://biosafety-info.net/articles/assessment-impacts/ecological/glyphosate-a-threat-to-insects-by-harming-their-symbiotic-bacterial-partners/

A few field observations from southern Chautauqua County, New York.

Earlier this summer, a large clump of volunteer native red raspberry canes that had sprung up on the edge of our abandoned wood pile (long story here), were positively humming with pollinator activity of all kinds, especially in the evening. The teeny yellow flowers on the female asparagus fronds also attracted hordes of pollinators.

Lightening bugs were abundant and seemed to last longer, almost into August.

We have bluebirds as a group of neighbors maintain houses, painted bluebird blue, of course.

The chart with the red-tailed hawk as top predator reminded me that there seems to be a decline in the numbers of this bird, beginning last season. They have been ‘replaced’ (driven-out?) by turkey buzzards, circling lazily overhead. (An omen? Bring out your dead?). I have heard the screech of a red-tailed hawk a few times in the last week, but have not seen any flying overhead.

A few years ago, I listened to a talk by entomologist Doug Tallamy, who started the “Homegrown National Park” movement. He stressed that baby birds must be fed with fat, juicy sluggish bugs, not ones with crusty carapaces. Or sunflower seeds. As with everything, quantity and timing are critical: no juicy bugs, no baby birds.

We have been planting hedgerows of native trees and shrubs in the old farm fields surrounding the house. It’s a hard slog because each one must be caged to protect it from the ravenous deer, who are multiplying like …. rabbits, until it is mature enough and tall enough to put it out of reach. I sometimes (well, often) think that the endeavor is fruitless. The deer are winning. Until they eat everything, and then die from famine and disease. So thankful that we humans would never conduct ourselves in such an irrational manner.

in tuscany we had a plague of deer. this seemed to begin around 2000 and the deer changed the floor of the forests, eating, killing most plants. tuscans, very tradition-bound, preferring boar, don’t eat venison and so don’t hunt deer. a few years ago special hunts were authorized for deer but not much changed. what has, in the past three years or so, greatly reduced deer population is the new presence of wolves. they knew where to find food. shepherds are not happy and must take extra measures. boar have adapted by joining families together into very large packs–we saw maybe 50 together–the large ones can fight off wolves.

Wolves will definitely keep the deer population in check! They were all killed off here in the 1800’s. Funny though, whenever I suggest this to my neighbors who bemoan the deer eating everything from the rose bushes around their house to their corn and strawberry field crops, they give horrified cries of ‘No, definitely not!’

I am guessing, from the reports of wolves seen in the north-eastern part of New York State, that the wolf-signal will go out that there is food ‘out west.’

We had two clutches of catbirds this year, with lots of organic layer for them to work through, millipedes especially. We supplemented with rehydrated mealworms for extra protein, and five of the six may have moved on.

Catbirds, incidentally, are of the Thrasher family, and when they want to be, have a marvelous creative song.

Since turkey vultures eat dead things which they find, whereas red tailed hawks eat live things which they kill, I doubt the turkey vultures would be driving out the red tailed hawks. Something else must be reducing the red tailed hawks.

Here in SouthEast Michigan I see a fair number of red tailed hawks the same as I always have. Decades ago I used to see steady numbers of kestrels, but in the last 20 or so years hardly any. Peregrine falcons are starting to recover, nesting on tall buildings as if they were natural cliffs, and eating the resident pigeons.

We have some peregrine falcons nesting right on the U of M campus in Ann Arbor, and they don’t mind the students and professors at all.

I remember reading that many Indian Nations ran large areas of landscape as “managed deer gardens” and killed and ate deer.

Since modern suburbia is essentially a collection of landscape-wide deer gardens, perhaps modern suburbanites and shallow-country denizens might set up systems for annual deer-culls by professional shooter-teams and field butchery-dressery teams to prepare the meat for distribution among the suburban jurisdiction-loads of people contracting with such deer-harvesting services. Doing a modern version of what the Indian Nations persons did. ( But not in areas where the deer are known to have Mad Deer Disease, unfortunately).

thousand points of green, annual deer culls by professional shooter-teams and then distributing the meat would certainly be one solution to the deer over-population. If predators (wolves or humans) don’t keep the deer numbers down, famine and disease will do it.

Here in Georgia on my 2 acre plot I have insects everywhere and must wear long sleeves and jeans when I garden due to biting insects. I also have 10’s of tiny frogs/toads in the garden every year. Nothing has changed here so far. Many dragonflies of all colors inhabit the yard, keeping out mosquitoes. No deterioration in 12 years. Lots of fireflies this summer.

We make annual summer road trips from the tip of Baja to the Pacific Northwest and back, and have definitely noticed a shocking decrease in bug splats over the last 35 years. In the 80s and 90s the front of the car would be completely plastered with bugs, now it’s usually pretty minimal. We live in an area with a lot of commercial agriculture, and the bee and other insect populations here, are small a fraction of what they once were before the explosion in the use of new fangled pesticides, which is to be expected, but between here and the California border there are huge stretches with no agriculture, and there’s the same noticeable dearth of insects

Summer of 2031: Seven-year-old boy, that allegedly harmed last butterfly, gets beaten to death by angry environmentalists, who use anything they have at hand, including big jerrycans of Neo¹-Glyphosate.

¹This time it’s really harmless