By Lambert Strether of Corrente.

Everybody knows what chokepoints are — think a robber baron stretching a chain across the Rhine to collect tolls — but nobody seems to have noticed how ubiquitous the checkpoint concept is, or in how many contexts it appears. I wish this post could be a unified theory of chokepoints, but it’s not. (If collecting material automagically produced a theory, I’d be golden, but it doesn’t, not even with AI). Instead, I hope readers will indulge me in my passion for maps. There are probably contractors The Blob laying out maps of global chokepoints for wargaming even as you read now!

Maritime chokepoints are top-of-mind for most people — I have to add “-maritime” to my searches to get decent results — so I will cover maritime chokepoints first. Then I will define the chokepoint concept to make clear how broad the concept really is. There are two ways of looking at chokepoints: As nodes in a network (pipelines, undersea cables, the supply chain, and traffic flows) and as standalone nodes (food, weaponry, technology). After that I will consider how chokepoints are affected by their environment, and how multiple chokepoints can be layered in the same face (Egypt, the Persian Gulf). I will concluded with a brief note on “chokepoint capitalism” (back to the robber barons!).

I hope this superficial review of various types of global chokepoints will infuse your reading with new insights, and perhaps in a few inspire thoughts of how actual choking might be instantiated. To maritime chokepoints–

Maritime Chokepoints

From Phys.org in 2022, “New analysis maps out impacts of marine chokepoint closures“:

Cargo ships move about 80% of all international trade by volume and about 70% of it by value. Much of this trade passes through one or more marine chokepoints en route to its destination. Pratson estimates that value of trade through a number of these chokepoints, such as the Malacca Strait and South China Sea, rivals the GDPs of the world’s largest economies.

Furthermore, some chokepoints, such as the Danish Straits, Bosporus Strait, Strait of Hormuz, East China Sea, and South China Sea, provide the only access to maritime trade for a large number of countries.

If these chokepoints are shut down or if traffic through them is reduced for a prolonged period, as has happened in the Bosporus Strait during the war in Ukraine, the disruption can block or severely limit affected countries’ ability to import or export goods their economies and world markets alike depend on. This can cause volatility in global supplies and prices and spur a scramble by nations and businesses on both sides of the chokepoint to secure alternative sources or markets for critical goods.

Here is an example the shows intuitively what happens to one maritime chokepoint — the Red Sea — during a war:

How the world changed in 10 days

A time-lapse visualizing the Houthi blockade at Red Sea chokepoint. pic.twitter.com/D3E582scEf

— Prop. co (@propandco) January 1, 2024

I suppose if I were in the business of writing clever headlines, I’d try: “From Chokepoint to Flashpoint. More seriously, from National Geographic, “This small strait is essential to global shipping. Now it’s the center of headlines“:

The Bab el Mandeb is a small geographical chokepoint in the Red Sea with an outsized influence on world affairs: It’s the key to the control of almost all shipping between the Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea via the Suez Canal. Recent drone attacks on commercial shipping in the Bab el Mandeb by Yemen-based Houthi forces have prompted a coalition led by the United States to launch military strikes against targets controlled by the militants. And while the Bab el Mandeb is currently making headlines, it’s also played an outsized role in human history—here’s what you should know.

Like so many maritime chokepoints, it’s a narrow strait, and therefore hazardous:

The name Bab el Mandeb means “Gate of Tears” or “Gate of Grief” in Arabic, from “bab” meaning “gate” and “mandeb” (or “mandab”) meaning “lamentation.”

Its name appears to refer to the perils of navigating the narrow waterway, which is rife with crosscurrents, unpredictable winds, reefs, and shoals. Many ships in past centuries and millennia wrecked in the Bab el Mandeb, and modern ships also face the dangers of naval mines from bygone conflicts.

Here are three examples of maritime chokepoints represented as maps, by Chatham House, the Visual Capitalist, and the Boston Consulting Group. You will note subtle differences between them, showing the flexibility of the concept:

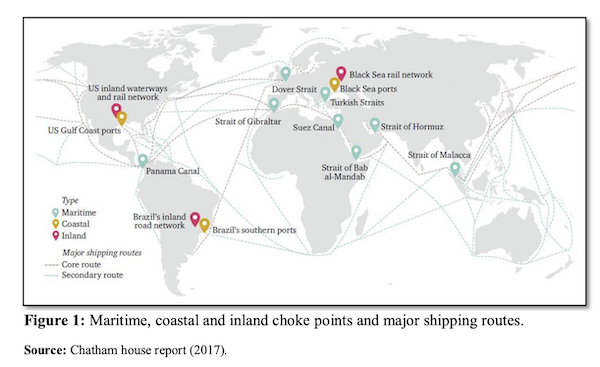

From Chatham House (2017), “Chokepoints and Vulnerabilities in Global Food Trade“:

International trade in [food] commodities is growing, increasing pressure on a small number of ‘chokepoints‘ – critical junctures on transport routes through which exceptional volumes of trade pass. Three principal kinds of chokepoint are critical to global food security: maritime corridors such as straits and canals; coastal infrastructure in major crop-exporting regions; and inland transport infrastructure in major crop-exporting regions.

And the map:

The map does indeed represent not only maritime corridors, but types coastal and inland infrastructure. (Food, however, not represented as a chokepoint, although that’s a possibility, as we shall see.)

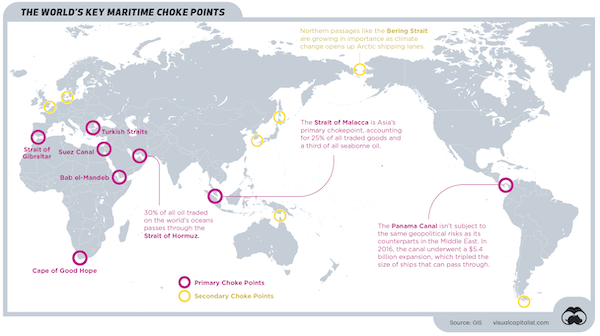

From the Visual Capitalist (2021), “Mapping the World’s Key Maritime Choke Points“:

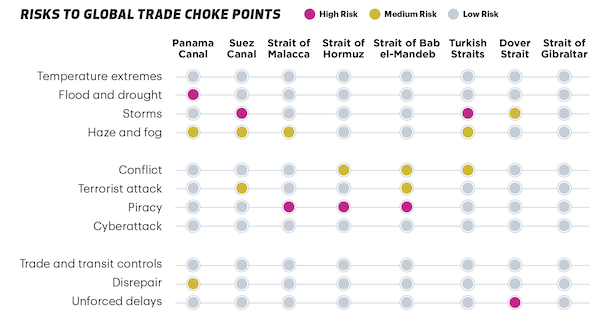

Visual Capitalist’s map does not represent coastal and inland infrastructure; they do, however, have explanatory captions. They also have a handy chart of risks in maritime chokepoints.

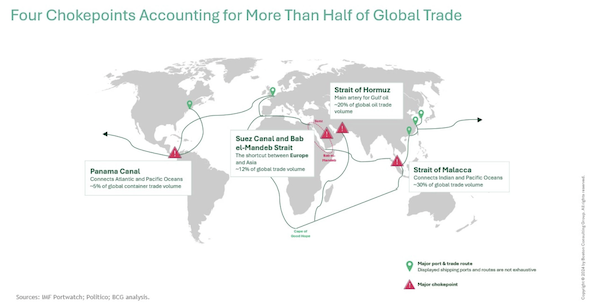

Finally, the Boston Consulting Group (2024), “These Four Chokepoints Are Threatening Global Trade“:

Right now, more than 50% of global maritime trade is at threat of disruption in four key areas of the world.

While the conflict in the Red Sea has been high in the news agenda, there are three other maritime passageways that risk becoming chokepoints due to either geopolitical or environmental factors.

I would say that a chokepoint does not “become” but is, and there are more than four. Here is the BCG map:

BGG’s map differs from the other two in that routes are captioned as well as chokepoints.

Chokepoint Defined

Here are three more formal definitions. From LIMN:

A chokepoint is a narrow corridor, a structural feature that restricts flow. Chokepoints are parts of a system that threaten to become a site of congestion or blockage, where movement might be stopped with very little effort. The network is often imagined as a form that routes around or bypasses chokepoints, but all networked systems still have at least one chokepoint. In most cases, they contain many bottlenecks, pressure points, and points of failure. This is true even for apparently distributed systems like the internet.

(“Restricts flow” like the robber baron. Or the Houthis.) Oxford Reference:

A point in a computer network through which all or most of the traffic in the network flows. Such points are vulnerable to both crackers and hardware failure. One of the main strategies of network designers is to minimize or eliminate the number of choke points.

And Wikipedia:

In military strategy, a choke point (or chokepoint), or sometimes bottleneck, is a geographical feature on land such as a valley, defile or bridge, or maritime passage through a critical waterway such as a strait, which an armed force is forced to pass through in order to reach its objective, sometimes on a substantially narrowed front and therefore greatly decreasing its combat effectiveness by making it harder to bring superior numbers to bear.

To me, all these definitions describe the same network structure, just in different fields using different terms. Now let us look at several networks besides maritime checkpoints.

Chokepoints as Networks

Here are several self-explanatory examples and maps.

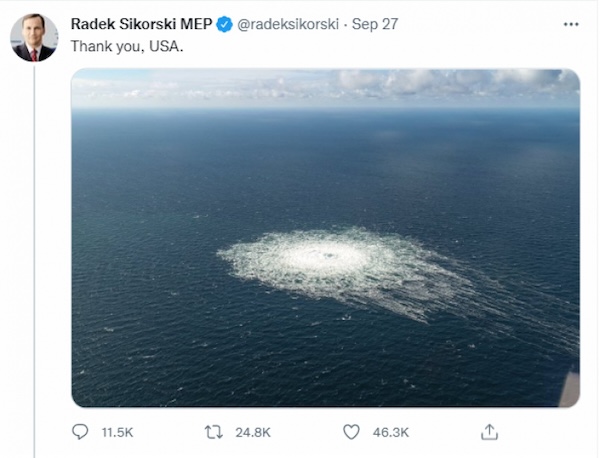

Pipeline chokepoint:

(You have to imagine the network of this is node is a (terminating) part.)

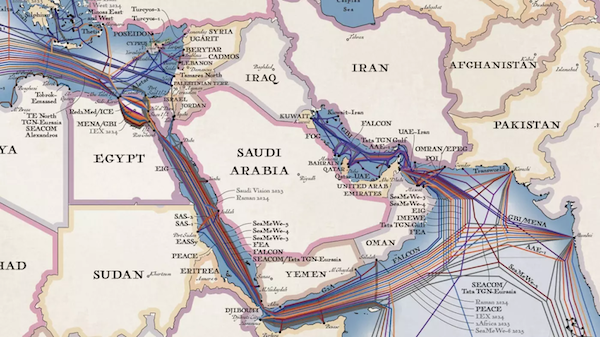

Undersea Cable chokepoints. From LIMN:

Our undersea cable system forms the backbone of the global internet. The most frequently discussed and debated chokepoints in this system are geopolitical chokepoints. For example, if one looks at the map of the undersea cable system, it’s easy to locate where cable routes funnel through narrow geographic zones. These include the Strait of Malacca (between Malaysia, Singapore, and Indonesia), the Strait of Luzon (between Taiwan and the Philippines), and the crossing of Egypt and the Red Sea. At each of these points, cable traffic is rendered vulnerable not only because of geographic constraints (e.g. a canal, submarine topography), but also political constraints (including both national, territorial, and oceanic politics) that make it difficult to route elsewhere. Forced along a narrow path, cables often are subject to an increased threat of anchors, subsea movements, and nations and companies that control the space.

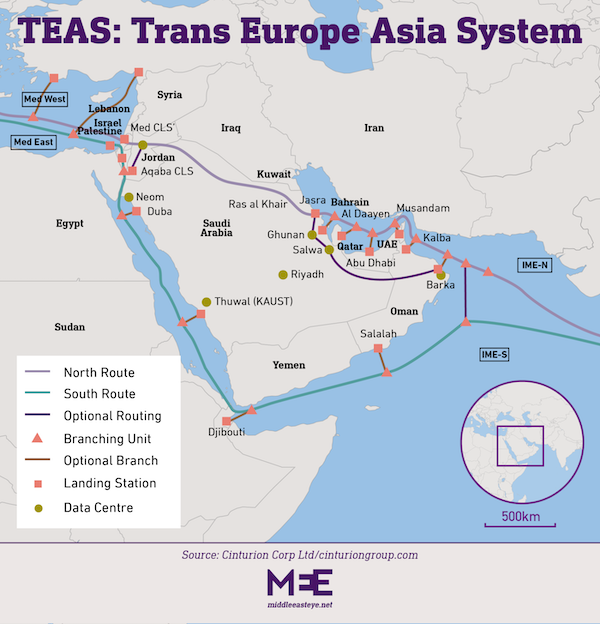

Here is an example of the Saudis strategizing on how to avoid cable chokepoints with cables on land, and not sea. From Middle East Eye, “How Saudi Arabia is redrawing the map of the future with fibre-optic cables“, the current map:

And the new map:

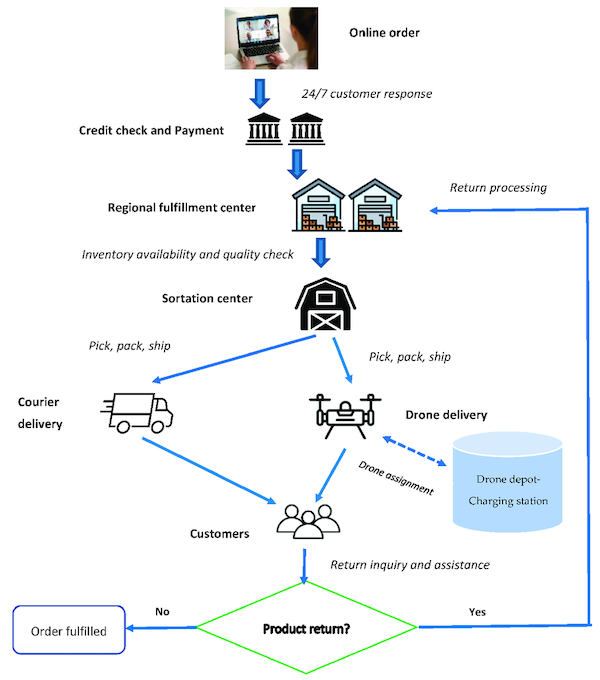

Supply chain chokepoints. From ResearchGate, “Leveraging Drone Technology for Last-Mile Deliveries in the e-Tailing Ecosystem“:

Yes, the sortation center is a chokepoint. So is the credit check (especially if that network goes down).

Somewhat farther afield, but showing once again the flexibility of the concept, traffic chokepoints. From Human Transit, “Chokepoints as Traffic Meters and Transit Opportunities,” No map (sorry), only prose:

The lesson of Seattle is that successful transit infrastructure responds to demand, and what drives transit demand is high overall travel demand plus serious barriers to driving. In Seattle, a lot of the barriers to driving take the form of hassle and delay, due to limited capacity through chokepoints

Seattle’s advantage, in short, is a natural scarcity of transport routes, which is the same as an abundance of chokepoints. Because of this geography, even in the era when we were building roads everywhere, it just wasn’t possible to build an oversupply of roads connecting the various parts of Seattle. So transit’s advantage remains.

Effective transit infrastructure aims for the chokepoints, and seeks an advantage there. This is part of why various forms of Bus Rapid Transit have particular potential in Seattle: if you give transit an advantage through the chokepoint, you can achieve a lot of mode shift. The bus services across Lake Washington (between Seattle and its eastern suburbs) on I-90 do well because they have preferential access through a major chokepoint.

Chokepoints as Nodes (Network Implied)

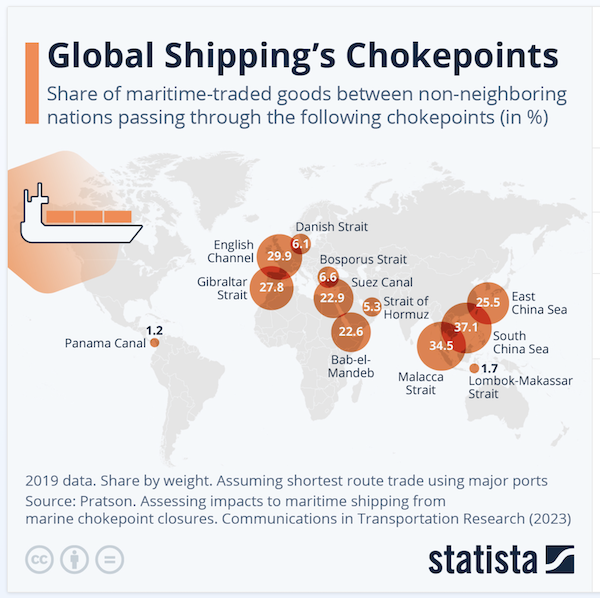

Here is an map that only shows shipping volume at any given node, living the network implied. From Statista, “Global Shipping’s Chokepoints“:

Here is a chart that takes the same approach, for weaponry:

Excellent. They may have (had) 150,000 missiles, but the LAUNCHERS are a crucial chokepoint. https://t.co/8f1eLCsidU

— Mitzi Rimon (@MitziRimon) August 25, 2024

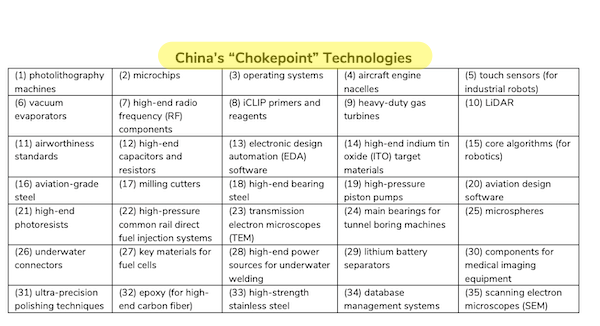

Here is a chart that takes the same approach, but for technologies. From the Center for Security and Emerging Technologies (PDF), “Summary of Chokepoints: China’s Self-Identified Strategic Technology Import Dependencies“:

One again we see the flexibility of the concept.

Influencing Chokepoints

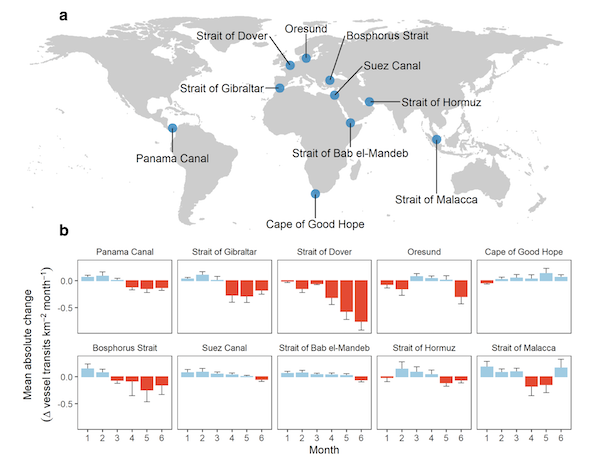

Chokepoints can be affected by their environment. From Nature, “Tracking the global reduction of marine traffic during the COVID-19 pandemic“, a chart (chokepoints marked in blue):

New chokepoints can also affect old chokepoints. An interesting historical example from Mozambique from the Center for International Maritime Security:

Then came Suez:

The Suez Canal, opened on 17 November 1869, drastically reduced shipping times and costs for trade between Asia, Europe, and the Americas. This ended the Mozambique Channel’s longstanding and central function as the indispensable link between Asia and the West, relegating it to a supporting role.

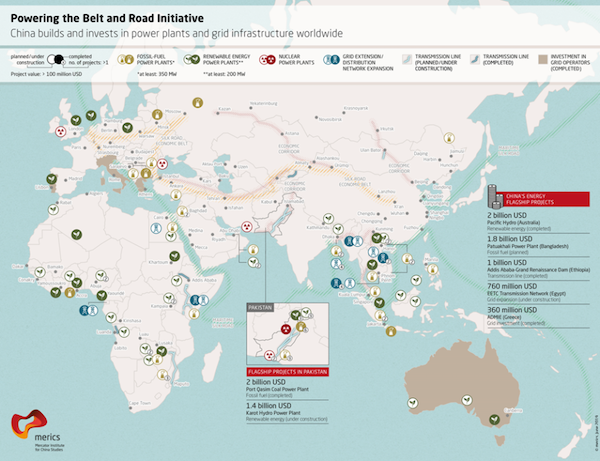

A more contempary example would be China’s Belt and Road initiative. From Rising Powers, “Ten Maps to Explain Climate Change and Geopolitics“:

One might regard Belt and Road as an enormous attempt to circument the maritime chokepoints set up by the West with a new network of chokepoints, but land-based.

Conclusion

It may be that the chokepoint concept is coming into its own, for good for ill. From the Financial Times (2024), “Charting trade chokepoints: a how-to guide“:

Last year, the commerce department launched a Supply Chain Center, to work with private sector partners on supply chain mapping. It has now begun quietly trialing a supply chain exposure tool that crunches trade and customs data from the US and many of its allies to create a detailed picture of where risks and opportunities lie.

The idea is to figure out how healthy — or not — these countries really are when it comes to supply chains in a variety of sectors, such as semiconductors, critical minerals, consumer electronics and so on. How quickly could critical inputs be replaced from allies in case of war, a pandemic or a natural disaster? How much do they depend on others from a single nation, such as China or Russia?

“We wanted to create a common operating picture and shared set of facts for supply chain discussions with allies in Europe or nations that are part of the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework,” says assistant secretary of commerce for industry and analysis Grant Harris, who created the new centre. “Our baseline for those discussions too often had been, ‘we should all do more,’ and then things would stall, because we didn’t have the data for a more detailed conversation.”

It sounds like a no-brainer, but as someone who’s been concerned with supply chains since the Rana Plaza factory collapse in Bangladesh in 2013, this is the most granular US government effort that I’ve seen so far to map global chokepoints in a broad range of commercial sectors. (I’d caveat this by noting that the departments of defence and energy have their own efforts targeted to their specific areas of interest.) According to several supply chain experts I spoke to, no other nation — apart from China — is doing more in terms of such cross-border mapping.

Meanwhile, very much outside the Commerce Department, we have the concept of “Chokepoint Capitalism”:

Chokepoint capitalism. @doctorow https://t.co/xMJtYTV4Dc

— DosGoats (@dosgoatsfilms) August 12, 2024

And those of you who considering internal expatriation might do well to consider where the next chokepoints might be:

Meanwhile, this 'realness' is situated along the St. Lawrence Seaway – the navigational chokepoint between the open ocean and 20% of the earth's fresh water. Massena feels like a wise and sleeping giant – the forgotten land whose geography may again build an empire. pic.twitter.com/ZRO3YzjgK9

— 𝙷𝚒𝚌𝚔𝚖𝚊𝚗 (@shagbark_hick) October 18, 2022

Readers, more examples from your own encounters?

The Port of Catoosa outside of Tulsa, OK is major national/international chokepoint for oil, gas, ag commodities and potentially photovoltaics (if a plant for them is actually built). Barges move even more freight than railroads. And way, way more than trucks on highways.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tulsa_Ports

It’s a site completely overlooked/ignored by activists (labor and environmental) who could use direct action to shut it down and cause pain all over the country. And it’s a port on a river, which is a lot less water than coastal actions have had to cover in the past.

I would argue that the lack of effectiveness for most direct action is tied to having a strategy that refuses to target local and national chokepoints, like airports and ports, and using the much less effective strategy of engendering moral outrage which retains the calculus of the powerful giving dispensations (if the media deigns to notice — see the pointless suffering and complete defeat of the ‘water protectors’) instead of the powerless taking power and dictating terms, at least in my experience as an activist.

> moral outrage

Moral ourage -> NGO funding

Some thoughts from me on strategy the next time I take this up. I’m really glad somebody got the point immediately.

Where there is a checkpoint, there is labor….

Love this post, Lambert.

So important to teach kids geography; it’s one of the most rewarding points of departure for understanding the world.

> Love this post, Lambert

[lambert blushes again]

Three aspects of chokes from mixed martial arts:

: A blood choke stops the blood going to the brain, and is a nearly instant out.

: An air choke stops air going to the lungs, and takes more time. This allows a response. The response may be panic.

: The correct response to a choke attempt is to tuck the chin. The choke done over the chin is called a jaw lock, and the pain and damage it can cause can force submission.

It’s a bit more than a metaphor, as the first two interrupt supply lines. The Ever Given was an instant out. An embargo takes time. If the subject can survive, the attacker must take care to not burn out their arms.

A painful chokepoint is represented by the uretras of the body. Kidney stones can be a killer…

> Kidney stones

One could think of the Ever Green as a kidney stone, yes.

Makes me think of that guy who’s name I can’t remember, but he defeated a ton of Romans as they moved along a narrow path. I think this is the one https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Lake_Trasimene

I have a large fat striped cat called Hannibal. Unfortunately, he adopts a Fabian strategy when it comes to rats and mice. But he is relevant to this discussion, since he always deploys himself in the choke-points of the house (especially as related to food dishes).

That great carthaginian general, Hannibal, was in the end defeated by this other great roman commander Scipio Africanus on the battle of Zama

A few years before that he also defeated Hannibal’s brother Mago Barca on another battle this time on the Iberian Peninsula…

The battle of Zama is one of the great battles of antiquity…

Anyway, fascinanting stuff from ancient times… just like this post about chokepoints!

Have to admit to a liking to the young Scipio Africanus rather than Hannibal who gets all the acclaim these days. He took the discarded, abandoned survivors of Cannae and built himself a world-class army that took on the veterans of Hannibal’s army at Zama in the end after clearing out Spain and Sicily.

To be fair, Hannibal, who, with his experience, could properly assess the strategic situation, was extremely reluctant to fight at Zama. He had few veterans from Italy left, and everything hinged on the timely arrival of allied cavalry (which did not come in time).

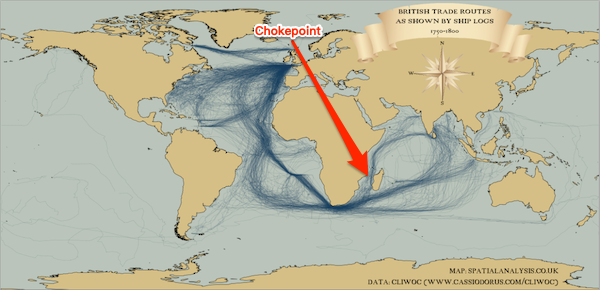

Prior to the late 19th century, much British overseas expansion have primacy to the acquisition of chokepoints, so that the UK could exert the maximum amount of power for the least amount of cost. The great cartographic expansion of empire occurred a little later, when the UK sought to prevent other European powers from gaining land, and when a greater quantity of territory became necessary to secure overseas markets once most of Europe and the US retreated behind tariff barriers.

Julian Corbett was the leading exponent of the importance of chokepoints to British imperial policy, as noted here in an excellent recent study: https://yalebooks.co.uk/book/9780300250732/the-british-way-of-war/

From a review of Corbett by the Western Front Association (!):

First, the “time-honored methods” are a theme of Patrick O’Brian’s Aubrey and Maturin series (I’m a fan).

Less trivially, one wonders if the Neocons, starting with “Project for the New American Century”, accomplished a similar “distortion” and “disarticulation” of American grand strategy. Probably not, given the debacle that was Vietnam, but it’s interesting to speculate about.

If we define a choke point as a node which dominates many downstream nodes, either at all times or under certain conditions, we should think more about water chokepoints. Not just the narrows but the shallows, for example:

– the Rhine shallows (nothing can pass in dry summers)

– the Lower Danube (often impassable in any summer for long periods)

– the GIUK gap (Greenland, Iceland, UK) for the deep water Atlantic that is preferred by submarines over the North Sea

We should also consider man-made choke points, other than the great transoceanic canals.

– the Old River Control Structure on the Mississippi (if the control gates fail, the river will switch course to a new delta and strand both New Orleans and the petrochemical plants on the lower river and canals

– the Three Gorges dam

We should also think about mountain passes. The Alps and the Pyrenees contain many chokepoints. But so do the Atlas mountains, the Caucasus, the Himalayas, the Altai etc.

The whole of Afghanistan is a chokepoint between Asia north, south, east and west!

Vital navigational rivers drying up (or flooding to excess) will be a major transport issue. Both the main Chinese rivers (plus the Mekong) are having supply problems, which will get worse as the glaciers melt in the Himalaya. When you look at the main axis of development in nearly every part of the world, they are based on navigable waterways. Its absolutely central to industrial development.

Strictly speaking, the main Silk Road route went north of Afghanistan, along the Fergana valley towards Kashgar. For various geopolitical and engineering reasons it was bypassed over the last century or so as it proved easier to build railways on the flatter, longer route north. Mongolia of course created its own deliberate chokepoint by choosing a railway gauge different from China and Russia.

We can’t forget of course that some smaller countries deliberately avoid becoming part of a chokepoint as it can make them a target for larger neighbours who suddenly have an excuse to muscle in for ‘vital strategic’ reasons. Bhutan, for example, has resolutely refused to allow any road or railway to connect to China, and the various ‘stans have generally been cautious about becoming part of a major transit route. Sometimes the safest thing for a country is to ensure they don’t appear on any maps of vital geopolitical links.

> Both the main Chinese rivers (plus the Mekong) are having supply problems, which will get worse as the glaciers melt in the Himalaya.

Another way of saying this is that China owns Vietnam. I am sure there are a lot of minds in Vietnam concentrated on what happens if/when the Mekong is choked.

Indeed – it is a huge issue in Vietnamese internal and external politics, not least because China has a very strong influence in Cambodia and Laos. The Cambodians are building a very environmentally and economically dubious canal providing another link to the Tonle Sap which has significant implications for Vietnam. Combine this with rising sea levels and the Mekong Delta is doomed. This is one of several reasons (see also, South China Sea) why Vietnam has been so keen to rebuild connections with the US. It sees China as its historic rival and potential enemy, not the former colonial nations (the Vietnamese are surprisingly unbitter over the American War. Its easy to be magnanimous when you win).

Controlling the headwaters of any major river gives you a stranglehold over the downstream countries. This is why China’s control over Tibet is so important – it gives them control over the major rivers of India, Bangladesh, and the Mekong.

> f we define a choke point as a node which dominates many downstream nodes,

I think is nearly restates the definitions given above. However, this definition includes the possibility of a network so massive and well-designed that flow cannot be interrupted. For example, if the Suez canal were a mile wide, say, then the Ever Green would not have choked it. Of course, Suez (and Egypt generally) would be chokepoints for other reasons, but not that one. I guess what I’m saying is that nodes and arcs are typed, and when instantiated, materiality matters.

Hence the existence of the Russian Poseidon nuclear powered and armed torpedoes with their specialised submarines. This was a Soviet era idea which the material science of the time couldn’t support. These are strategic weapons and their main targets ( the carrier major repair ports and the big canals ) are probably unchanged with a few modern add-ons because of the upgraded importance of world trade in a WW3 scenario. They are not port city killers by design.

I think that you can also add technological choke points to that list. We saw with the recent Crowdstrike fiasco how a few minor errors ended up crashing 8.5 million systems around the world-

‘The outage disrupted daily life, businesses, and governments around the world. Many industries were affected—airlines, airports, banks, hotels, hospitals, manufacturing, stock markets, broadcasting, gas stations, retail stores, and more—as were governmental services, such as emergency services and websites.’

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2024_CrowdStrike_incident

So what other technological vulnerabilities are already in place that we do not know about – yet.

> So what other technological vulnerabilities are already in place that we do not know about – yet.

I could speculate; but you can be sure there are both state and private actors focused on that very point.

Great post, full stop! I love reading things like this, thanks for the effort.

One thought I have had for a many years that relates to this is the role inventories plays/have played. From buffering seasonality in agriculture (storing grain until the crops are harvested, which is tied to the role of debt), to manufacturing in discontinuous processes.

As the world has pushed to just-in-time for everything, thank you management consultants and the PMC that doesn’t really understand things, we have removed some of the natural buffers to shipping delays, nee chokepoints.

At some point this will backfire. Though it likely does regularly, its just not described that way.

> Great post, full stop! I love reading things like this, thanks for the effort.

[lambert blushed modestly].

That’s a very very good point, JIT giving chokepoints more impact. Risk on, as it were.

But nearly all of these potential “chokepoints” have never been choked, except by rare weather events.

Both the West and China are afraid that the other may choke the Strait of Malacca but none have done so.

If someone did, the alternate routes are just less convenient and somewhat more costly, just a bump.

It is the supply dependencies (noted at the end) that present risks, but the players seem to accept those.

The vast chip fab in Taiwan was known from the start to pose a US dependency on good China relations.

It was put there by the US, but instead the right wing militarists cite it as a risk posed by China.

So now they can put economic entities on the borders of other powers to support false claims of threats.

> But nearly all of these potential “chokepoints” have never been choked, except by rare weather events.

Past performance is not indicative of future results. Especially as systemic stresses increase.

Thanks Lambert.

Here’s another one:

https://law.stanford.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Global-Patent-Chokepoints.pdf

And while the term chokepoint might make sense some of the times mentioned above, I’ll stick with intentional/unintentional bottleneck. Simply to consciously make an effort to refrain from unnecessarily brutalising my language any further.

Fascinating. Thanks for posting.

> bottleneck

I think chokepoint is the better term because it connotes the aggressive act of choking.

Response to froghole, re British imperial policy and choke points,

The way it’s been explained to me, is that Uruguay as an independent country is a result of the chokepoint in the Rio de la Plata which connects the inland Network to the ports of Montevideo and Buenos Aires.

Uruguay is along the south side and east side of that River and before it became an independent country it was fought over by Argentina and Brazil. Spaniards and Portuguese. After quite a lot of fighting the English stepped in and created Uruguay so that the river would be international waters. So chokepoints can be a good thing!

DoomPr0n.

I’ve been in the Largest Naval Convoy Post WW2 during the IRAQ-IRAN Gulf Wars.

The Bab-el-Mandeb is a Choke point; and the Houthi have been harassing shipping for some time.

They simply started getting armed with Missiles and Drones, then started targeting them on Commercial Shipping and Israel after 07October.

The Houthi claimed to target Ships doing business with Israel or Ships with HQ’d Countries aiding Israel; but that’s not the situation.

The Houthi – supplied by Iran – have been arbitrarily targeting Merchant Shipping.

Murica, NATO, €U, CHN, and IND have their Naval Warships in the Region.

Murica, NATO, and the €U have their own Convoy/Interdiction Operations. IND are involved because their Shipping and Crews staffed by Indians are being attacked. CHN already chastised IRN – warning them to curb Their+Houthi enthusiasms or lose the China (SCO/BRICS/BRI) Trade.

Murican and NATO Naval Ships were intercepting Missiles+Drones sent to Israel and on Merchant Ships nearby.

Murica+NATO have taken a “Supportive, Backup Muscle” in the Mediterranean Region regarding the 07October War – Delta Force sent to Jordan to protect the King, Erdogan had his “Neck Stepped On” within days by (Non-TRK) NATO Force Positionings (e.g., SpecOps (Special Operations Forces for Civilian Readers) on Cyprus), so all he could do was whine.

Murica and GBR have attacked the Houthi; but on a limited, measured scale so to keep the Houthi engagement isolated and to prevent Nation-State Actors from engaging Israel and escalating the scale of the War.

Keeping Israel’s War – Israel’s War. I don’t agree with Brandon sending in SpecOps(Special Forces for the Civilians)

This Site doesn’t have the Military Slant, so Readership need to go elsewhere for the Discourse.

What did all these Strait and (Suez) Canal Choke point Maneuvers result in?

Most Merchant Shipping sailing around the Horn of Africa – a disruption to the Traffic – with increased Fuel+Insurance costs relayed to the Customers.

So a few Naval Convoy Protected and risk taking Merchants traverse the Strait of Bab-el-Mandeb; and EGY are losing Suez Transit Fees.

End of the World? No. Will there be other Choke points Terrorized? maybe the Hormuz; but the Iranians can’t shut it down for the general public – they have to play nice because they recently joined BRICS+, which have KSA, UAE (across the Strait), and CHN as Members.

Hope you can rest assured.

Have a good day; and sleep tight tonight!