Lamebert here: Whaddaya know.

By Alessandra Bonfiglioli, Professor of Economics (on leave) at Queen Mary University Of London, Rosario Crinò, Professor of Economics at University Of Bergamo, Gino Gancia, Fellow, International Trade and Regional Economics, and Ioannis Papadakis, Research Fellow at University Of Sussex. Originally published at VoxEU.

Harnessing the potential of artificial intelligence has become one of the top priorities for policymakers around the world. Yet, doing so first requires a thorough understanding of the effects of these technologies on labour markets. Using data across US commuting zones over the period 2000-2020, this column presents evidence that AI adoption has reduced employment, except in high-paying occupations and those requiring a degree in STEM disciplines.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is often viewed as one of the most transformative and disruptive technologies of recent times (see early Vox columns by Baldwin 2018 and Bughin 2017). Thanks to improvements in machine learning techniques and the growing availability of vast amounts of digital data, the last two decades have witnessed a tremendous increase in the use of AI applications, which include web search engines, targeted advertising, recommendation systems, generative or creative tools, and chatbots. A pressing policy question is how these advances will affect labour markets and especially employment. On the one hand, intelligent tools promise to enhance human capabilities and create new demand for certain skills (e.g. Brynjolfsson et al. 2023, McKinsey Global Institute 2017). On the other hand, AI may surpass workers in decision-making tasks and make them redundant, or it may fuel automation (Acemoglu 2022, Acemoglu and Johnson 2023). Whether AI will complement or substitute workers is therefore an empirical question, for which there is still little systematic evidence.

In a recent work (Bonfiglioli et al. 2023), we study the employment effect of the early phase of AI adoption, exploiting variation across US Commuting Zones (CZs) over the period 2000-2020. Taking a broad definition of AI as algorithms applied to big data, its diffusion started in the early 2000s and accelerated after 2010. While our sample predates the development of large language models such as ChatGPT, it nevertheless covers the rise of the digital economy and of all the major companies involved in big data collection, such as Amazon, Google, and Facebook.

Measuring AI Adoption Across US Commuting Zones

Our analysis faces two challenges. The first is that AI adoption is difficult to measure, as there are no official statistics available to date. However, the use of AI technologies requires workers with very specific programming skills. Leveraging a novel section of the O*NET database – “Hot Technologies” – we classify AI-related occupations as those whose job postings most frequently require software used for machine learning and data analysis. Our baseline classification of AI-related occupations comprises 19 titles, such as data scientists, computer programmers, software developers, and web designers. Then, we detect AI adoption from the growth in the relative importance of these AI-related occupations. A second challenge in identifying causal effects is that AI adoption might be correlated with other shocks that may affect employment. To overcome this problem, we use a shift-share instrument, AI exposure, that combines industry-level AI adoption for the US with pre-adoption CZ-level employment shares across industries. This allows us to identify CZs more exposed to AI as those specialized in industries that experienced faster growth in AI-related occupations nationwide.

Between 2000 and 2020, the employment share of AI-related occupations has almost doubled in the US, rising from 0.14% to 0.20%. Most of this increase has taken place after 2010. There are sizable differences in the diffusion of AI technologies across industries. AI adoption is most prevalent in the service sector, especially in advanced branches such as information, professional, scientific and business services. It is also important in some utilities, such as electricity, and in some areas of the public sector, such as national security and international affairs. Conversely, AI adoption is still limited in manufacturing. This feature distinguishes AI adoption from the use of industrial robots, which is mostly concentrated in the manufacturing sector (Acemoglu and Restrepo 2020).

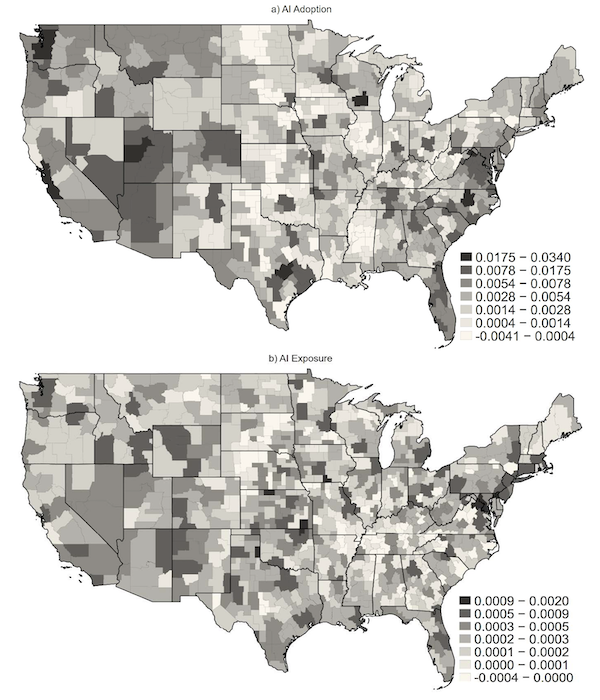

Figure 1 presents colour maps showing how AI adoption (panel a) and AI exposure (panel b) vary across US CZs, with darker colours representing higher levels of adoption or exposure over the sample period. Negative values are very rare (only 6% of CZs), implying that the deployment of AI technologies has been a widespread phenomenon in the US over the last two decades. Interestingly, our measure of AI adoption (panel a) is very effective at capturing the diffusion of AI both in expected places such as Boston, Seattle, and Silicon Valley, and in new high-tech hubs such as Boulder, Bozeman, and Salt Lake City. Our measure of AI exposure (panel b) removes the variation in AI adoption that is more likely to be driven by contemporaneous CZ-level shocks, which may confound the estimation.

Figure 1 AI Adoption and AI Exposure in US Commuting Zones

Source: US Census and American Community Survey.

Notes: The top map plots the average value of the measure of AI adoption in each CZ between the decades 2000-2010 and 2010-2020. The bottom map plots the corresponding values of the measure of AI exposure.

The Negative Effect of AI Adoption on Employment

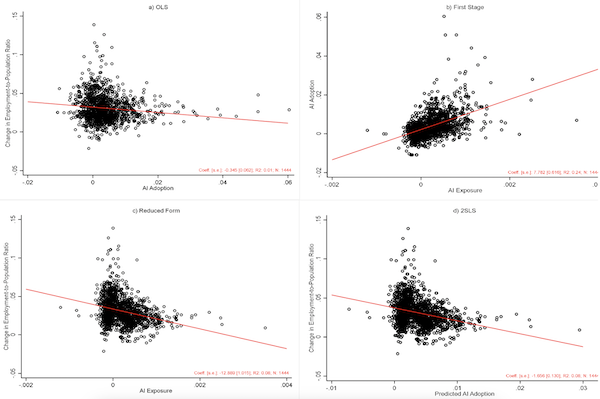

Figure 2 provides a graphical representation of our empirical strategy and main results. The dots in each of the four scatter plots represent observations for each CZ and decade (2000-2010 and 2010-2020), while the red line is the linear regression line. Panel a (OLS) documents a negative correlation between AI adoption and the decadal change in the employment-to-population rate at the CZ level. Panel b (first stage) confirms that AI exposure is a strong predictor of AI adoption and, thus, a powerful instrument for the deployment of these technologies. Panel c (reduced form) shows that AI exposure is strongly negatively correlated with employment growth. Finally, panel d (2SLS) plots the relationship between AI adoption, as predicted by AI exposure, and the decadal change in the employment rate, highlighting a strong negative (causal) effect of AI adoption on employment growth. Overall, these graphs show that CZs specialised in sectors experiencing a boom in AI-related employment had stronger rates of AI adoption, which in turn caused them to suffer a relative slowdown in employment. Quantitatively, our estimates imply that if the CZ with average AI adoption over the sample period had hypothetically had no adoption at all, its employment rate would have grown by 0.6 percentage points more.

Figure 2 AI Adoption, AI Exposure and Employment in US Commuting Zones

Notes: The estimation sample consists of 722 CZs observed over two decades, 2000-2010 and 2010-2020. In each plot, an observation is a CZ x decade pair. Predicted AI Adoption is the fitted value of the measure of AI adoption from the first-stage regression in Plot b).

These results are robust to controlling for several additional labour market shocks, such as import competition from China (Autor et al. 2013), the adoption of industrial robots (Acemoglu and Restrepo, 2020), and the increased usage of ICT. They also hold when using alternative definitions of AI-related occupations and when controlling for outliers in various ways.

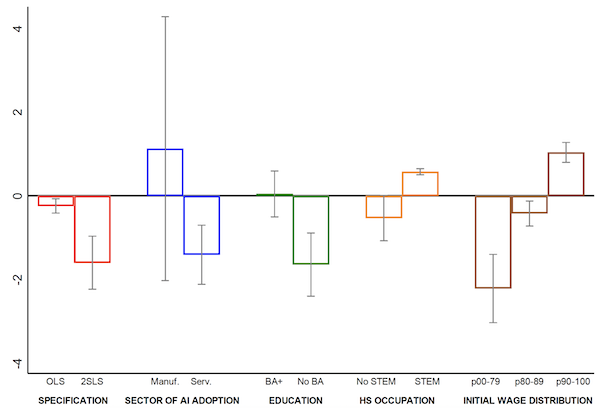

Figure 3 shows how the relationship between AI adoption and employment growth varies across specifications. The figure conveys three main results. First, the effect of AI adoption is much stronger when AI adoption is instrumented using AI exposure (2SLS versus OLS specification), suggesting that confounding factors tend to mask the negative impact of AI on employment. Second, the effect of AI is driven by adoption in the service sector, where the deployment of these technologies is more prevalent. Third, workers without a college degree are the most negatively affected by AI adoption. Conversely, the only workers to benefit from AI adoption are those in occupations requiring a STEM degree and those in the top 10% of the income distribution.

Figure 3 Heterogeneity

Notes: The figure reports estimated coefficients and 90% confidence intervals on the measure of AI adoption from different specifications. The estimation sample consists of 722 CZs observed over two decades, 2000-2010 and 2010-2020.

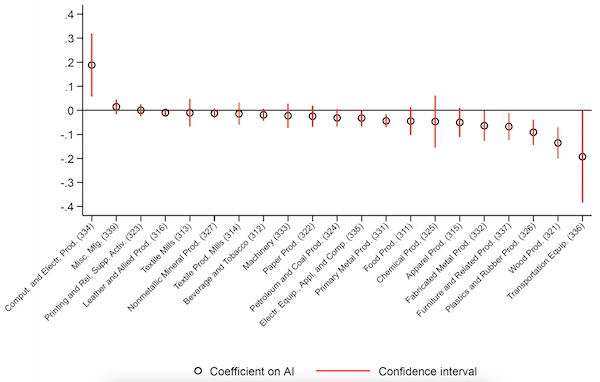

Our results also show that the negative effect of AI adoption is not limited to the service sector but also extends to employment in manufacturing, where the use of these technologies is still limited. Specifically, the manufacturing sector accounts for almost 45% of the overall impact of AI adoption on employment, against 60% for the service sector. To shed light on the mechanism underlying these spillovers, Figure 4 reports the estimated effects of AI adoption on employment in the different manufacturing industries. The figure shows that workers in industries characterised by high automation intensity, such as transport equipment and wood products, are especially hard hit. This suggests that AI adoption in services may, in fact, be used for the automation of jobs in manufacturing.

Figure 4 AI Adoption and Employment in Individual Manufacturing Industries

Notes: The estimation sample consists of 722 CZs observed over two decades, 2000-2010 and 2010-2020.

Conclusions

Recent improvements in the field of AI have triggered much hype about the future of work. While nobody can predict the exact direction that new innovations and applications will take, we think that it is important to start from understanding the consequences that these technologies have already had. Our results point toward robust negative effects of AI adoption on employment for most workers and sectors. While more micro-level evidence is needed to precisely identify the mechanism through which these negative effects unfold, our evidence is nevertheless consistent with the view that AI is contributing to the automation of jobs and to widening inequality.

Advances in technology may have taken jobs away from portrait painters and coachmen, but they have created new professions such as photographers and chauffeurs. AI will create unemployment in the short term, but in the long term it will create new jobs for the times.

I understand what you are saying, buggy whips, whale oil candles and all that.

Any speculation to what those jobs would be? Other than more workers at any type of power generation plants that will be needed for the power demands of AI going forward?

Lots of jobs will be the same – just humans who use AI to enhance their skills: computer programming, art, creating movie scenery, video games, etc. It will lower the costs of creating and barriers to entry in many fields. More of these creations will be produced (i.e. animated movies) as the skills required diminish. If NC were AI-enhanced and moderated, it could probably produce 10x the high-quality content with the same people. But hosts would need to invest time into getting the AI to help…and it would likely be a lot of time….like playing a musical instrument. Might not be worth it if you’re nearing retirement but necessary for those in school.

Locksmithy, security, and teaching low/appropriate tech self-reliance. Much available on-line, but hands on locksmithing / trades are A I proof. Jackpot/ dystopia.

Oh, and pick a broligarch mecca, like Greece, Davos, Sun Valley, Jacson, central crowdorado, Western WY, MT, Hamptons, eastern Coastal New England, Florida enclaves. Put a siphon on the arses of the superiors, the ones who poop jasmine-scented guru-certified hand-chewn expeller-pressed Oregon-tilth artisanal Ice Cream.

And keep your humor!

\sarc\

“Prompt engineers” *rimshot*

Yep, the long term….

https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/6757924-in-the-long-run-we-are-all-dead-economists-set

Either something is done to make the benefits of automation and AI more equally distributed or we can just do nothing (because in the long term then all will be well again after the market has done its thing).

Are those new jobs going to address this?

Conversely, the only workers to benefit from AI adoption are those in occupations requiring a STEM degree and those in the top 10% of the income distribution.

our evidence is nevertheless consistent with the view that AI is contributing to the automation of jobs and to widening inequality.

Automobiles were once a luxury for a limited number of wealthy people, and driving was a highly specialized skill. No one thinks that way anymore. Like automobiles, AI will become a useful tool that everyone can use in their work and daily lives as it becomes more widespread.

uh huh. Didn’t think I was arguing that the lower economic strata wouldn’t have “access” to ai, although I imagine there will be a monthly bill. AI’s contribution to the wealth gap is where my concern lies.

Weren’t “they” promising us shorter work weeks, more income and possibly some sort of Universal Basic Income which would make it all wonderful for everbody?

For kids in the 1950s and 1960s the kids were told, via cartoons, that their future would be one of leisure with a little work. Because robots would do the drudge work.

Houses would be automated so you just had to press a button for dinner. Men would go to work in cute flying cars, and be home in daylight to play with the kids. The future would be so exciting, so good. So kind to people.

Reality:

Farming. Once the comfortably well off and rich owned land to buffer them from poverty

Factories: Then when the bottom mostly fell out of small mixed farming they learned a trade skill like boilermaking and worked in a factory to to keep themselves from poverty

Corporate Professional: Then manufacturing was moved off shore so they went to college and earned a good degree and that buffered them from poverty.

But now AI is replacing these jobs too. So where are the new jobs?

AI is cheaper at creative, so not there.Computers are cheaper at organising, categorising, analysing. So not there. Robots are cheaper to build cars and are starting to build houses. So not there.

Where do you think all the homeless and the addicted and the jailed come from? Do you think they were born that way? Maybe, just maybe, the relentless pursuit of the super rich in getting the cheapest and most obedient workers (robots and computers) had a hand in this.

Sorry, reply was meant to ciroc at the top

I assume you foresee an increase in human manned complaint centers and legal aides for handling suits against AI errors?

I wonder what impact AI might have on retail and wholesale sales? I will avoid AI like I avoid auto-driving Tesla’s and self-check out at stores. I just do no know what I might do if I suffer the benefits of too many more improvements like AI.

My SWAG is in the long term, AI will increase unemployment for most, pushing labor costs down, increasing employment and compensation for a few, which will increase profitability. Otherwise the highly monopolistic, lightly-regulated, Western economic leaders (aka major corporate boards) would not develop and implement AI.

The lower two panels in FIg. 2, to my eye, do not look like a single linear fit is appropriate – it looks like there are two clusters of data, one very weakly related to employment and one very strongly related to employment. I am surprised that got by the reviewers. By analogy, it’s like a single fit to a sex-related health problem without separating men from women into two data populations. Its guaranteed wrong, probably following how each sex was represented, not health outcomes.

Reminds me of a good movie I once saw with the following tag line….Show me the money!

As to the “proof” that AI is doing anything other than a gigantic money sink, the article gleefully descends into could be, might be, maybe will be, we suppose, hard to measure, and finally the final descent into colored maps proving the ability of what I do not know. Somehow a field in Ohio went from light grey to darker grey. And this is considered proof?

Show me the money!

First they have to raise a few more billions to replace the ones they wasted. AI = BS.

I admit to not having read the piece yet. Do I want to read something by someone called Lamebert? Sounds like a Scott Adams character.

*smile*

A friend who teaches English literature at a state university tells me about how chatGPT in particular has made his workload much higher, as too many students have taken to writing their essays this way, sometimes with minor modifications before submission. So now he has to check all the quotations and footnotes to make sure they’re not invented, among other things. I half-jokingly suggested he could mark his papers by feeding them through chatGPT as well, to which he assured me some of his colleagues were already doing that.

One can apply the same thinking outside the humanities, to any number of skills.

One can imagine the long-term effect of this attitude to be a societal de-skilling on a massive level, when the training data starts to rely on data that was generated by AI (this is already starting to happen), which produces garbage much faster than you would imagine, and you have a generation who never learned how to do the basics themselves.

For now, I have to admit, it can be useful, as long as I look at chatGPT as a hardworking and somewhat dishonest intern who takes dangerous shortcuts.

I would have to think long and hard before adopting an AI. It costs too much to feed one. Buying and running a place to house one would bankrupt me. Besides, there is something creepily off about their cute faces. The text-drooling would get all over my carpet and shoes. Yuk! And I would be afraid one would give me a serious bite out-of-the-blue.

Remember when the much hyped (in the 1980s) nanotechnology was claimed to threaten us with the whole world turning into gray goo? Nanomachines drowning out all natural biological organisms?

Well, ChatGPT and its ilk will turn the whole information sphere into intellectual gray goo. Sentences and paragraphs and whole tomes of post-truth factoids and memes endlessly regurgitated. You’ll know nothing and you’ll reason not at all. And you will be happy.

“Negative values are very rare (only 6% of CZs).” That is to say, CZs in which the adoption of and exposure to AI has been declining. Ah, is there an alternative path right here in the belly of the beast?

The maps (Figure1) show a very few. One is directly north of New York. It turns out to be CZ 151, consisting of the counties Putnam, Dutchess, Rockland, Orange, Sullivan and Ulster. Woodstock Nation? half/sarc

Maybe AI will be directed against David Graeber’s “bullshit jobs”?

In that case, the opportunity was highlighted by Graeber in August 2013.

https://www.davidgraeber.org/wp-content/uploads/2013-On-the-phenomenon-of-bullshit-jobs-A-work-rant.pdf

Manual jobs, like the replacement of a 2000 Toyota Camry passenger side power mirror I did last Sunday, will be difficult for AI to accomplish directly or assist with much.

I’d guess the local automotive shops charging $185/hr for labor are not fearful of the AI revolution.

No, current “AI” is directed against those jobs producing any kind of output found a few million times on the net: photographers, designers, graphics editors, summary writers and so on.

Bullshit jobs rarely produce content, so “AI” can’t imitate them.

Yes, that’s still far in the future.

A lot ot workers in the automotive shops will lose their jobs because cars get ever more complicated and repairs will (not in every case, but often) be replacements of larger modules. It’s already happening.

Regards, Uwe