Yves here. Richard Murphy works from some recent examples of financial market panic to contend that most secondary market trading is societally unproductive. It therefore amounts to rentierism and should be curbed.

There is a large body of evidence supporting Murphy’s claim. Studies by the IMF and others have found that overly large secondary market trading activity is correlated with lower growth. And “overly large” is not all that big. The IMF found in 2015 that Poland represented the optimal level of financial “deepening,” which crudely is the level of finance versus real economy activity. From our post on that article:

As the world has floundered in low growth post-crisis, with advanced economies still suffering with credit overhangs and hypertrophied, largely unreformed financial services sectors, it has become acceptable, even among Serious Economists, to question the logic that a bigger financial sector is necessarily better. Of course, the logic of “more finance, please” was never stated in those terms; it was presented in the voodoo of “financial deepening,” meaning, in layperson’s terms, that more access to more types of financial products and services would be a boon. For instance, one argument often made in favor of more robust financial services is that they allow for consumers to engage in “lifetime smoothing” of spending. That basically means if times are bad or an individual has a big investment they to make, he can borrow against future earnings. But we have seen how well that works in practice. Most people have an optimistic bias, so they will tend to underestimate how long it will take them to get back to their old level of income, assuming that even happens, which makes it too easy for them to rationalize borrowing rather than going into radical belt tightening ASAP. And we’ve seen, dramatically, on how college debt pushers get students to take on debt to “invest” in their education, when for many, the payoff never comes.

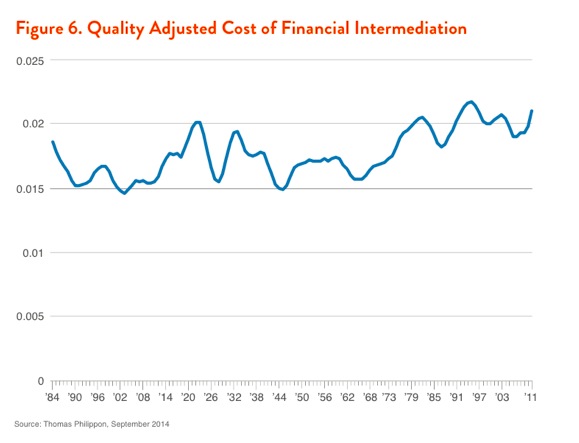

Moreover, despite an enormous increase activity and widespread use of technology, costs of financial intermediation have increased, as Walter Turbewille shows, citing a study by Thomas Philippon:

But the recent IMF paper, Rethinking Financial Deepening: Stability and Growth in Emerging Markets, is particularly deadly. Even though it focused on the impact of financial development on growth in emerging markets, its authors clearly viewed the findings as germane to advanced economies. Their conclusion was that the growth benefits of financial deepening were positive only up to a certain point, and after that point, increased depth became a drag. But what is most surprising about the IMF paper is that the growth benefit of more complex and extensive banking systems topped out at a comparatively low level of size and sophistication. We’ve embedded the paper at the end of this post and strongly urge you to read it in full.

The Fund did argue that perhaps more would be non-detrimental if there were strict regulation….a practice that is sorely out of fashion.

Another telling factoid: asset managers are twice as likely to become billionaires as tech industry members.

There is a simple way to alleviate this problem: transaction taxes. But aside from the fact that these would discomfit the very rich and earn the wrath of the politically powerful financial services industry, it would also amount to an admission of regulatory failure. For instance, the SEC has been working hard since the 1970s to lower transaction costs, regarding more liquidity as ever and always good. The authorities should know better by now but are too invested in preserving their handiwork.

By Richard Murphy, part-time Professor of Accounting Practice at Sheffield University Management School, director of the Corporate Accountability Network, member of Finance for the Future LLP, and director of Tax Research LLP. Originally published at Fund the Future

So, the Japanese stock market crash of earlier this week, with its knock-on effects all around the world, was all about panic, and not about substance. The markets have, near enough, recovered. Almost certainly, some people made a great deal from the short-term confusion that arose. And now we are supposed to move on as if nothing happened.

Except that it did. Japanese stock markets did reveal how exposed they are to the risk that the Bank of Japan can create within them by raising interest rates.

US markets demonstrated how vulnerable they are to trades funded with borrowings in Yen.

Other markets showed their capacity to panic.

That does not mean we need to move on. Instead, it demands that we appreciate just how vulnerable the world is to the absurd consequences of permissible decisions by central bankers and others. That vulnerability exists because of the inappropriate assumptions made by some in financial markets that they can act as if there is no risk of change when such risk exists. As a result, they build edifices on the basis of false assumptions.

We saw this in the debacle that the Bank of England created by announcing £80 billion of quantitative easing in September 2022, which went on to panic markets that had built the so-called LDI trade on the assumption that such a thing would not happen in the way it was announced. The resulting panic brought down Truss. That might have been no bad thing, but it disguised the reality of what happened, which required considerable Bank intervention.

This time, it seems unlikely that any such thing was required: markets worked out they could manage the consequences of the Japnese carry trade changing.

But my point is that irrational market trades, undertaken for pure speculative gain without concern for the underlying supposed use of the assets traded, can have real consequences.

The question is, why do we allow such wholly unnecessary trades to exist when there is no real gain to society from them doing so?

I am not arguing against capital markets per se. I accept that they have a role. I accept that limited trading to provide liquidity for second-hand asset trades is necessary, given the way in which traded securities are issued and redeemed. However, the vast majority of trades in the vast majority of financial markets do not take place to provide finance for anything related to productive activity. They exist to extract speculative profit, and that is a burden on society at large, in my opinion, representing a vast waste of energy, resources and talent for no net gain, whilst creating considerable risk for society at large.

That is the lesson of this week.

It will be forgotten.

Link to the original posting: The irrationality of markets

Fixed, thanks!

This is a symptom not a cause. Unlimited borrowing of (new) money for no productive purpose will eventually reward unproductive people, whether they are trading houses, ships, trademarks or Bitcoin to get it.

“markets worked out they could manage the consequences of the Japnese carry trade changing.”

I guess if you are of the mind that something that has building up for years gets resolved in a couple of days…

Part-time Professor Richard Murphy may not be aware that, thanks to the internet every producer, farmer, rancher, business owner can “hedge” – a.k.a. lock in the profits and costs by utilizing “energy wasting” trading – sarc.

As an example, one can buy a crude oil ETF to lock in the present price of fuel, a gold ETF insures against the Central Bank’s mischief, currency ETFs are perfect tools for the cross border traders. Every business owner employs money market accounts to store cash. Every day countless rational individuals engage in trading for their own benefit and their well run “for profit” business operations benefit society at large as well.

I think it all depends on how large one’s ‘stake’ is in the transaction.

Nearly every “real money” participant you list in a financial market gets raped by the intermediaries. Hence the book “And Where Are The Customers’ Yachts…?”.

If you sit at the poker table and you cannot see the mark, it’s you.

(Not you personally, I just want to throw a bucket of cold water over the heartwarming tail of financialisations’ benefits that you are reproducing. The people making markets in hog backs, orange juice and energy futures are doing it for maximum profit, not altruism. And if they can make more money breaking markets, they will: I give you Enron (sadly true) in energy and Brewster’s Millions in OJ (hilariously fictional)).

I make most all my money in my sleep. So that makes me a rentier. It took quite a while to realize that I make almost no productive contribution to society, except maybe for a few partners who had little but now have much more. But my markets activity has almost nothing to do with trading or intermediating, and is very rare, sometimes many months between trades. I say this in order to also say, the world would be better if I could not do what I do, but rather had to do something that made tangible contribution. And then spillover from markets to the real economy might also go away.

You make most of your money in your sleep? I hope they leave the money on the dresser before they leave. ROFLMAO

Yes, the “loss” (by which I mean that the neoclassical orthodoxy hid it on purpose) of the distinction between earned and unearned income once central to classical economics has been enormously damaging to contemporary understanding and public discourse around inequality.

It’s another service of economic equilibrium attending to duty.

This duty of the informed and sophisticated is to take advantage of the uninformed and naive, for as long as they don’t fight back.