The US National Security Council (NSC) is currently working to develop a Black Sea security and development strategy across government agencies.

The current National Defense Authorization Act already outlines several pillars of that strategy that can effectively be boiled down to “keep Russia and China out and the US and NATO in.”

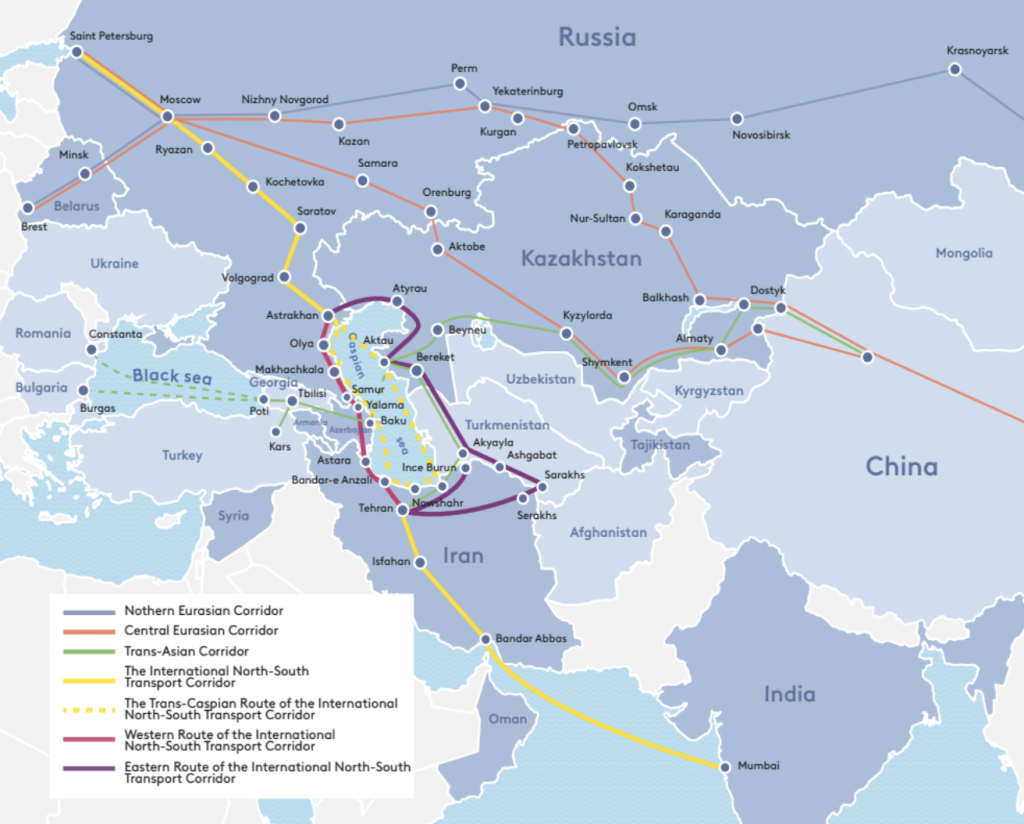

What that envisions is an arc of “rules-based order” states from the Caspian to the Adriatic that would allow the US to exercise control over the movement of energy and goods through the region, and especially in the South Caucasus, which is positioned at the intersection of burgeoning East-West and North-South transport corridors. As Assistant Secretary of State for European and Eurasian Affairs James O’Brien put it before the recent Senate Foreign Relations Committee subcommittee hearing “The Future of Europe”:

[We are] are working to foster deeper cooperation among the Black Sea states. But there remain challenges to democracy in some quarters, where backsliding is a significant concern. We must maintain our focus on countries like Georgia, working with like minded partners to promote measures that strengthen democracy and incentivize a return by these governments to a Euro-Atlantic path. In Russia’s periphery, we seek to help those countries that have struggled between the pull of EU accession and the pressure of Russia’s autocracy, and work with those leaders to get them out of the ‘grey zone’ and into western-style democracies. We are building a path for countries in the Western Balkans, Moldova, and the Caucasus independent of malign influence from the PRC and Russia. Some elites in that periphery are bucking against making the hard reforms needed to join the EU and NATO. We must work together to ensure those reforms are done.

It’s an ambitious goal. It’s also been a complete disaster thus far. In most cases, states in the region are now saying no thank you to US entreaties, ignoring its threats, and they’re moving closer to Russia and China.

US officials like O’Brien can talk about democracy all they want, but countries like Azerbaijan, Georgia, and all-important Türkiye are refusing to sacrifice their national interests in order to further the goals of American capital. Only landlocked Armenia is adhering to the US strategy as it follows Washington’s lead on its peace process with Azerbaijan, turns over its government to American advisors, and poisons its long ties with Moscow. More on that below, but let’s first take a look at the energy situation and the countries that are turning their backs on Washington.

The US Cannot Exclude Russia from the Region’s Energy Architecture

Central to the US plans is that it and its client states control the flow of energy resources from the Caspian region to the Black Sea and onto Europe. The US envisions this being done without any participation of Russia, but this ignores how integrated Russia is with its neighbors to the south — and how beneficial that relationship is for countries of the region.

Without even getting into Ukraine’s potential loss of its entire Black Sea coastline, it’s still bad news for Washington. Let’s take Türkiye. The Atlantic Council sums up the US position when is says “Türkiye can become an energy hub—but not by going all-in on Russian gas.” Washington wants Türkiye only to transfer gas from Azerbaijan and from across the Caspian. But here’s what is actually happening.

According to S&P Global, Russian gas supply in July via the TurkStream pipeline to southeast Europe reached the second-highest monthly volume level since the pipeline began operations in 2020.

In the never ending comedy that is the EU trying to wean itself off of Russian gas, Türkiye is even offering to increase the flow through the Turkstream pipeline into Europe. Ankara will, of course, accede to EU demands and only send gas from Azerbaijan. Then it will turn around and buy more gas from Russia for its domestic needs.

Money that used to be spent by the EU on Russian natural gas is simply shifted to Türkiye, but the revenue for Russia remains the same, more or less.

It’s a bit of a headache as Ankara needs to re-export the Azeri gas, but they make a nice little profit. For example, Türkiye and Bulgaria signed a deal in 2023 to permit Bulgaria’s state-owned Bulgargaz to import 1.85 billion cubic meters of gas per year. Bulgargaz has to pay a 2 billion euro service fee to Türkiye over a 13-year period. Türkiye is looking for a similar deal from the EU before further expanding Turkstream capacity. The EU, desperate to keep up the illusion that it is successfully navigating the end of Russian pipelines, will have little option but to accept any Turkish demands.

The West is trying similar math games elsewhere.While Ukraine’s contract to transit natural gas from Russia to Europe ends at the end of this year, and there have been no signs it will be renewed, EU officials want to use the pipelines to transit Azeri gas instead.

This is where it gets tricky. Azerbaijan has no access to the Ukrainian pipeline network, and the Azerbaijan pipeline to the EU is already at full capacity. According to Bloomberg, the EU is proposing a “swap” with Russia providing “Azeri” gas to the EU, while Azerbaijan sends “Russian” gas elsewhere. How exactly those details get worked out remains to be seen, but it would presumably allow EU officials to pat themselves on the back and say they’ve cut off Russian pipeline gas completely.

Meanwhile, the plan would add to the ludicrousness of the EU efforts as even the gas that is piped from Azerbaijan through the South Caucasus Pipeline, the Trans-Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline, and the Trans-Adriatic Pipeline has a Russian flavor to it. Due to Russian companies’ large investments in the Azerbaijani oil and gas sector, it is one of the bigger beneficiaries of Brussels’ efforts to increase energy imports from Azerbaijan in order to replace Russian supplies. Azerbaijan is also importing more Russian gas itself in order to meet its obligations to Europe.

The one spot where the US achieves some of its goals is the ongoing operations of ExxonMobil and Chevron in Kazakhstan that send the oil to the Black Sea. The great irony there is that success requires the cooperation of none other than Russia. ExxonMobil and Chevron are the largest shareholders in the Caspian Pipeline Consortium (CPC), which carries oil from Kazakhstan to the Russian Black Sea port of Novorossiysk and onto the global market. The majority of the CPC exports go to Europe and have historically provided about six percent of the EU’s total crude imports.

The US Gets Desperate in Georgia

When earlier this year Georgia passed a foreign agents law — which requires NGOs and media outlets that receive more than 20 percent of their funding from abroad to register as such with the government — it was the surest sign yet that the current government was turning away from the West. The reporting requirement for foreign-funded groups makes it harder for US- and EU-backed organizations to inconspicuously cook up color revolution attempts.

The West is predictably taking a scorched earth approach, complete with sanctions and a halt to Georgia’s EU accession process. More measures are working their way through the US Congress with the aim of passing them before Georgia’s October elections:

War criminal Putin should not be allowed to shape future of Georgia says @RepJoeWilson the author of MEGOBARI act in US Congress pic.twitter.com/FnveOENCra

— Formula NEWS | English (@FormulaGe) July 12, 2024

It is likely that the West is also preparing for another regime change attempt centered around this fall’s parliamentary elections. Georgia is already beginning to crack down on returning members of the Georgian Legion — a group of anti-Russian mercenaries fighting in Ukraine — who it says are plotting attempts to overthrow the government in Tbilisi. Moscow has also offered assistance to the government in Georgia in thwarting any destabilization attempts. Why such the uproar over tiny Georgia?

Assistant Secretary of State O’Brien mentioned one of the reasons recently before the Senate Foreign Relations subcommittee. In order for the US to call off the dogs, he said Georgia must end its agreement with China to construct a deep-water port on its Black Sea coast. There is also the Russian plan to reactivate a small Soviet-era military facility in Abkhazia.

This all runs counter to the US plans for Georgia, which include a transit route connecting central Asia and its vast resources of energy, metals, coal, and cotton to Europe and subsea power cables connecting South Caucasus energy to the EU.

Turkiye Prepares to Jump Ship

Türkiye controls passage to and from the Black Sea through the Bosphorus Strait and the Dardanelles and can ban the passage of naval vessels from non-littoral countries under the Montreux Convention, which it has steadfastly done since Feb. 2022.

But the Atlantic Council has a plan to change all that, which is “To engage Turkey, make it part of the plan.”

This highlights a central problem with the US and probably its most important (due to geographical factors) NATO “ally”: the failure to account for Türkiye’s interests when formulating plans. It’s a long running grievance from Ankara that its concerns are ignored while it is expected to act as a dutiful frontline soldier to protect the interests of American capital. This fundamental disconnect is finally coming to a head, and while letting Ankara have some input on the alliance’s direction sounds like a bare minimum wise move, what sign is there that the hubristic neocons are even capable of such humility?

Nevertheless, the Atlantic Council’s idea is flatter the gullible Turks by bringing them in on the plan, which to use the Black Sea Mine Countermeasures Task Force—launched in January 2024 as a trilateral initiative between Bulgaria, Romania, and Türkiye to clear their territorial waters of floating mines — as a Trojan Horse for getting warships into the Black Sea. Shockingly, Türkiye continues to resist such efforts — even though the Atlantic Council explained to Türkiye at the time of July NATO summit in Washington what are in its best interests:

Türkiye must understand that while it may gain immediate benefits from trade and energy cooperation with Russia, its economic and security interests are closely aligned with the West, not with autocratic regimes such as China and Russia. Doing business with sanctioned, unstable, and undemocratic countries is a major geopolitical risk and comes at a huge economic cost. Russia’s economy has become a war economy, and there is not much future in doing business with Moscow, especially with the prospect of secondary sanctions looming.

This is representative of the brain rot in Washington that refuses to acknowledge other countries interests and ultimately cannot or will not offer anything more than threats of additional sanctions or other measures. In many ways this particular Atlantic Council argument is not nearly as bombastic as other think tank screeds and official statements that demand Türkiye do as it is commanded or…or else!

Say what you will about Russia or China, but when it comes to international relations they typically try to respect other countries interests and aim for the much-loved “win-win” agreements, which, importantly, they usually uphold. In Türkiye, which is a regional power and where a large segment of nationalists harbor dreams of an ottoman world power in the 21st century, that approach plays well. For all these reasons Türkiye is moving ahead deepening economic and diplomatic ties with Moscow and Beijing.

Much is made of what an own goal US policy scored when it managed to drive Russia and China together. Possibly just as impressive is how American neocons have done the same with Türkiye and Russia. And it’s across the board — business ties, people-to-people ties, and governments. In most cases, the step up in Türkiye-Russia relations occurred with a direct assist from US policy. Consider just the following three examples:

- On nuclear energy: Türkiye inaugurated its first nuclear power plant last year — a major occasion in the country as it joined the ranks of nuclear power nations. Russia’s Rosatom financed and is building the plant that will provide roughly 10 percent of Türkiye’s energy needs once fully completed. But the backstory involves 50 years of Türkiye trying to get the West to build it a nuclear plant, which never came to pass.

- On defense: Ankara had asked NATO multiple times since the 1990s to deploy early warning systems and Patriot missiles (with tech transfer) to Türkiye, but Washington repeatedly refused. In 2017 Russia sold Türkiye its S-400 missile defense systems, which are arguably superior to anything the West has.

- On trade and tourism, the proxy war against Russia in Ukraine is the gift that keeps giving to Türkiye-Russia relations. Russian businesses have been setting up shop in Türkiye as a bypass route around Western sanctions. Russian tourism to Türkiye has gone through the roof due to travel restrictions put in place by the EU, and the increase came as a major boost to Türkiye’s floundering economy. Win-win, as they say.

Disaster for Armenia, Success for the West?

Much of the US plan to salvage anything from its Black Sea mess now rests on poor Armenia.

Assistant Secretary of State O’Brien told the Senate subcommittee that Secretary of State Antony Blinken and European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen “created a new platform for Pashinyan several months ago” that is allowing the Armenian government to break away from Russia.

At least publicly, the US and EU have committed hardly anything to Armenia. The EU recently launched a four-year 270 million Euro fund to help “bring Armenia into the Western fold.” Actually bringing Armenia into the EU would require significantly more than that, especially if Russia decided to scale back economic ties with Yerevan. As Fitch Ratings notes, Armenia’s economy relies significantly on Russia for both trade and energy. For example, Armenia also currently pays Russia $165 per thousand cubic meters of gas, well below the market price in Europe, and Russia is Armenia’s number one trading partner. According to the Armenian government data, it accounted last year for over 35 percent of the South Caucasus country’s foreign trade, compared with the EU’s 13 percent share in the total.

Nevertheless, the US takeover of Armenia continues. Last month, a State Department official said that a representative of the US armed forces will be stationed in the Armenian Defense Ministry. Armenian Under Secretary for Civilian Security, Democracy and Human Rights Uzra Zeya confirmed the decision, saying: “We welcome the deepening of civil defense and security cooperation between the US and Armenia. This marks a new phase in the strategic partnership between our countries.”

Indeed.

There seem to be two goals to the US strategy with regards to Armenia. The first is to turn it against Russia. To this end, the Armenian government and much of the media now blames Russia for any loss of territory in the country’s decades-long disputes with Azerbaijan. This, of course, makes no sense, but it is a line pushed relentlessly.

Meanwhile, Armenia continues to bring its armed forces up to NATO standards and increase interoperability. Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov recently outlined Russia’s concern:

“I hope, Yerevan is aware that any deepening of cooperation with the alliance may result in its losing sovereignty in the sphere of national defense and security,” Russia’s top diplomat said…

“This cannot but cause our concern. We have repeatedly drawn the attention of our Armenian colleagues to the fact that NATO’s true goal is to strengthen its positions in the region and create conditions for manipulation based on the ‘divide and conquer’ scheme,” Lavrov concluded.

The second component of the US strategy to use Armenia to further its goals in the region involves the increasingly important transportation links in the region. Both China-led East-West routes and Russia- and India-led North-South routes rely on passing through the Caucasus.

We can go back to O’Brien’s Nov. 15 comments during “The Future of Nagorno-Karabakh” House committee hearing for insight on the US intentions regarding these routes. Here’s what O’Brien said:

“A future that is built around the access of Russia and Iran as the main participants in the security of the region, the South Caucasus, is unstable and undesirable, including for both the governments of Azerbaijan and Armenia. They have the opportunity to make a different decision now.”

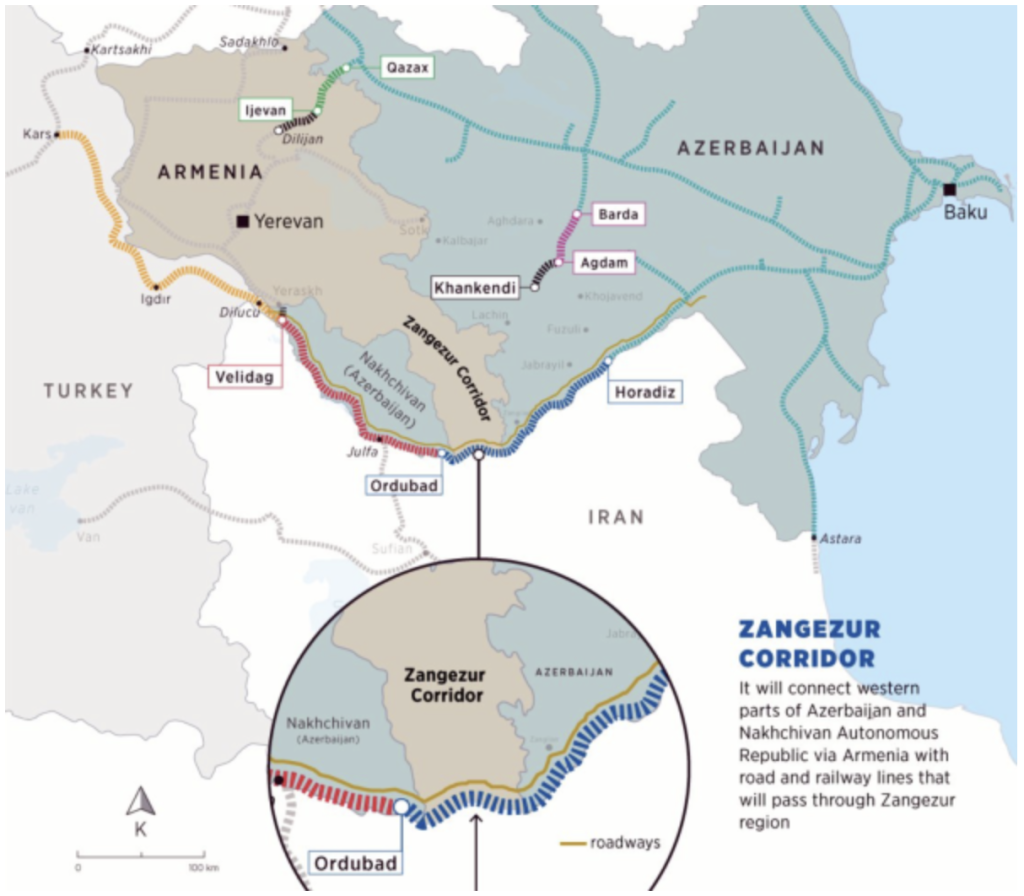

O’Brien further explained Washington’s preference for a land corridor between Azerbaijan and its Nakhchivan exclave to run through Armenia. So here we get to the point of the US efforts.

If the US cements peace between Armenia and Azerbaijan, gets an agreement on a trade corridor through Armenia, and continues to control Armenia, well, it then controls the trade corridor. That would be a success for the US.

“In our [U.S.] view, there’s a once-in-a-generation — maybe several generations — opportunity to build a trade route from Central Asia across to the Mediterranean. That can come only if there is peace between Armenia and Azerbaijan,” O’Brien says.

A central question for other countries of the region: why would they want international transport routes through the region controlled by the Americans? The answer is they do not.

Russia and Iran are obviously opposed to the American plans to cut them out. Iran, especially, worries about a NATO Turan Corridor which sees the West link up hypothetical client states throughout central Asia.

Azerbaijan and Türkiye — two linchpins to any US Zangezur Corridor deal — have shown no inclination to go along. They would prefer to work with the countries that are actually in the region rather than get on board with an American plan to destabilize the neighborhood.

There have recently been reports that the corridor through Armenia is being dropped from the overall peace plan as Armenia doesn’t want it, and Azerbaijan doesn’t want it under US control. It sure would be a shrewd move from Baku if it gets all the territorial concessions it wanted from the US-led peace process only to back out of the one component of the deal that the US actually cares about.

Azerbaijan has always preferred to work with the other countries of the region on the issue, but has participated in the US-led process at Armenia’s insistence. Azerbaijan’s president is actually hosting Putin today and the two sides are signing several agreements expanding cooperation and developing the countries’ strategic partnership.

This was always Armenia’s other option: come to agreements with neighbors rather than be used by a declining power a world away which is increasingly grasping at straws.

Instead it is now in a situation where all the other countries of the region are working together in pursuit of more logistical integration, as well as a desire to keep the West from sabotaging those efforts. This puts Armenia on a collision course with its neighbors, as the US would work to sabotage any corridor agreement it can’t control, and Armenia’s neighbors will not tolerate a US-controlled corridor. When that happens, it’ll be yet another fiasco for US foreign policy. And it will be a disaster for Armenia whose friends in the West will not be able to offer any meaningful defense support.

“It’s an ambitious goal. It’s also been a complete disaster thus far. In most cases, states in the region are not saying no thank you to US entreaties, ignoring its threats, and they’re moving closer to Russia and China.”

Mi guess is that there goes “now saying” rather than “not saying”.

Fixed! Thanks Ignacio.

Conor, I think there’s a typo in the following passage:

“It’s an ambitious goal. It’s also been a complete disaster thus far. In most cases, states in the region are not saying no thank you to US entreaties…” Does the word “not” belong there?

I really appreciate the wide geographic and political range of your posts!

Thanks for catching, Carla!

What this underlines is that economic, trade and political relations are and always have been very complex, and haven’t obeyed attempts to impose overarching political schemes on them. This was even true in the Cold War (for Greece, Turkey, not Russia was the enemy for example) and is more obvious than ever today. Plans and strategies are easy, but it’s the actors on the ground who really decide what happens.

Thanks for this long analysis. The US diplomacy effort is certainly using a “unique” strategy. They are demanding that the countries that they are leaning on give up billions if not tens of billions of dollars in earned revenues annually in return for letting Washington take control of their armed forces and their foreign policy. That sounds like an all-stick and no-carrot deal to me. Years ago Georgia listened to them which led to the Russian-Georgian war of 2008 in which they lost two provinces permanently as well as over 420 dead soldiers and civilians alone. And here is Rep. Joe Wilson wanting them to go for round two? Yeah, I can see why these countries would prefer to cut a deal with China and Russia instead. And I do not see Azerbaijan letting Armenia have a throttle-hold of a major trade route through this US Zangezur Corridor deal. Armenia is picking a fight with every single country surrounding it so clearly was future war-zone marked all over it. So, not a great plan.

Yes, it looks like Armenia is being set up. Only problem I see is that if Georgia does not play ball and the US manages to alienate Turkiye (further), then how will the US supply Armenia?

How can Armenia not see this? Just look around at all the wreckage around the world following this type of US interference. Are leaders simply bribed and plan on fleeing?

Armenia is now Ukraine mark 2. Nice work, State Dept ghouls! Destroying Countries R Us!

The dollar is us most effective weapon. I assume that when countries do things so obviously against interest money is changing hands.

The whole plan is delusional in light of the Ukraine war and Russia’s rapidly expanding influence world wide and especially with the BRICS countries..Being on Russia’s border and engaging in anti-Russian activities is not a good plan for any country…But the State Dept is no doubt “just following orders…”

That’s a great question, one which it’s incumbent on Armenia to ask for itself.

As for the U.S., they’ll simply dump their patsy/proxy when things get too rough. Of course, some of the more helpful locals will be extracted to America.

So in answer to the “who is running the US government” question it sounds like the answer is James O’Brien. Thanks for the above which makes the head spin with all the obscure plotting. Doubtless under the upcoming Kamala administration the US will continue to pour treasure and somebody else’s blood into goals that seem equally obscure to we the humble many.

I don’t think US goals are at all obscure. Quite simply, Washington wants complete world-domination and is will to spend what it takes to get it done this is ridiculously simple to understand. Washington has turned itself into a bunch of comic-book villains. It sends out “diplomats”, cover-operatives, soldiers to bribe, assassinate, their way to Empire. They are like ants busy at their endless tasks to subvert and try to destroy societies including our own for the pleasure of being part of a grand enterprise. These people are exactly what those of us who grew up in the 50’s heard about communism’s (centered in Moscow) plan for complete world-domination which, btw, Moscow was not that interested in but it was a convenient way to amass power within the US to create an Orwellian enemy easy to caricature since most Americans had then and have now no idea of the richness of Russian culture. Similarly, most Americans have no idea whatever of the richness of Iranian or Chinese culture so they are earily led by the nose by a brilliant minde-control regime under Washington’s control. This will continue until they run out of money which, considering the absurdly bad US education system (just had a conversation with someone in the Charlotte school system).

One prop for the British Empire was primogeniture which meant that lots of second and third sons had no place to go other than the military or off to the colonies to help run the thing on which the sun never set. This has been talked about around here with regard to the US and our own current excess of aristocracy. Presumably running the world, as Biden puts it, is a good gig with foreign travel, nice office and salary, and future employment with the Atlantic Council or some other plutocrat boosting think tank. The billionaires always have lots of cash to spread around among their minions.

Of course when Sitzkrieg turns to real war the minions can find empire a lot less cozy. An entire generation of British died in WW1 much as is happening with that same generation of young men in Ukraine. History wise we have learned nothing and forgotten nothing. The Baptists used to say the meek will inherit the Earth–if there’s anything left of it. Here’s hoping we last that long.

Yes, but young men from the US are not dying (in large numbers–covert ops and mercenary work people are dying) at least officially. The difference with Britain is that their Empire was called an Empire and rich and poor alike were willing to die for it. After Vietnam, Afghanistan, and Iraq and damage I’ve seen to those that have come back, few want to go to war these day except through gaming–all imperial wars will be done with foreign troops (lavishly paid for) mercenaries and, eventually, robots.

I’m glad they’re getting something, ‘cos they ‘ave an ‘ell of a time…

After the waters are polluted and the lands are poisened….

Yes, and there was a formula:

1st st son gets the land

2nd Son goes into the army

3ed Son goes into the Church.

Or perhaps the answer is, “whoever is whispering into James O’Brien’s ear.”

A few years ago, when I was a sailor on an American warship that visited Batumi, I got a chance to talk to the US ambassador. I asked him what the US was doing to promote democracy in the region. His answer to me (I was 23 at the time, and very Foreign Affairs-pilled) was that a role of the embassy mission was to introduce contemporary American social movements to Georgia, to “liberalize them.” He specifically spoke about #MeToo, and how it needed to come to Georgia. In hindsight, this ties in neatly with the NGO-sphere in Georgia, as a cudgel of ideas to make young Georgians more sympathetic with a cosmopolitan and avant-garde West. This was 2019.

Interesting to see this strategy failing, especially in light of the NGO transparency bill.

The biggest threat to “democracy” is who people have let define it.

One wonders how the Atlantic Council can write such delusional tripe with a straightface:

“Türkiye must understand that while it may gain immediate benefits from trade and energy cooperation with Russia, its economic and security interests are closely aligned with the West, not with autocratic regimes such as China and Russia. Doing business with sanctioned, unstable, and undemocratic countries is a major geopolitical risk and comes at a huge economic cost. Russia’s economy has become a war economy, and there is not much future in doing business with Moscow, especially with the prospect of secondary sanctions looming.”

Hard to see anything in the quote that reflects reality –

To take one example of relevance. Bombing Nordstream 2 was undemocratic, promoted instability at a huge economic cost, and was against a friendly nation!

While the Atlantic Council clearly cannot, I can imagine (the almost assassinated) President Trump 2 (on a domestic vendetta) causing instability. Just can’t wait to see how well the cluster f of US sanctions on China will go – after all, the Russian sanctions have done a wonderful job screwing Europe (friendly nations!).

Policy formed in denial is doomed to fail.

Elliott had a handle on this particular facet of the Western propensity to ignorance in the Four Quartets: “Go, go, go, said the bird: human kind cannot bear very much reality”. “For last year’s words belong to last year’s language and next year’s words await another voice.”

US economy has increasingly become a „War Economy“ which is why National Debt and Budget Deficits have exploded as Monetization of Debt has expanded Credit Expansion in U.S. economy.

“Nevertheless, the US takeover of Armenia continues. Last month, a State Department official said that a representative of the US armed forces will be stationed in the Armenian Defense Ministry. Armenian Under Secretary for Civilian Security, Democracy and Human Rights Uzra Zeya confirmed the decision, saying: “We welcome the deepening of civil defense and security cooperation between the US and Armenia. This marks a new phase in the strategic partnership between our countries.”

It seems that a tell-tale sign is “snap elections.” Anywhere they are seen, suspicions should arise.

Wiki:

“Snap parliamentary elections were held in Armenia on 20 June 2021. The elections had initially been scheduled for 9 December 2023, but were called earlier due to a political crisis following the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War and an alleged attempted coup in February 2021.”

Snap elections everywhere these days…

Conor, thanks! Excellent article!

Romania is seeing some interesting developments:

Work on Largest NATO Europe Base Begins in Romania

https://www.thedefensepost.com/2024/03/21/largest-nato-europe-base-romania/

This should be under the protection envelope of the Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense System already in Romania:

Deveselu Military Base

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deveselu_Military_Base

It’s hard to see the wisdom of these large fixed bases in this era. It seems like the worst possible thing you could do in a time of vast numbers of hypersonic missiles and perhaps tactical nukes. “Here’s all our stuff! Come and get it!”

They also provide an easy surveillance target for anyone interested in keeping an eye on enemy personnel and materiel. And of course they ensure that your city and country are part of the enemy target package for when The Big One happens.

What could it take for the USA to give up on total military and financial domination? Nothing seems to faze our ‘leaders’, including losing multiple wars in a row, the backfiring of sanctions, the lack of honest diplomacy etc. Of course some people are making a lot of money, so apparently it’s all good.

The US financial system is built on debt, the top 10 companies in the S&P 500 apart from Tesla and Nvidia are corporations that produce no concrete physical goods. Meanwhile American infrastructure is crumbling from lack of investment, life expectancy is dropping, and public health care is worse than a joke. You have to marvel (or cry) at the upside-down world that has been created.

“What could it take for the USA to give up on total military and financial domination? Nothing seems to faze our ‘leaders’, including losing multiple wars in a row, the backfiring of sanctions, the lack of honest diplomacy etc…”

Have they really felt any personal, adverse consequences for their actions? What are the institutions that will hold them accountable? When?

The revolving doors in the halls of power continue…

It seems the U.S. is hoping against hope to sustain the imperium, even though the rest of the world sees it as circling the drain. How such short-sighted, morally-depraved people remain in power is dismaying. I heard of a recent poll where young people, on a list of primary concerns, saw Palestine rank around 14 of 15. These probably aren’t callous people, they just aren’t aware the barbarity of our actions in the world. (And climate change ranks in the same area in polls). As Charlie Brown would have it, “sigh.”

Thanks Conor. Clarifying. Following our intended path for oil straight to the EU, only pausing at every border entry for western financiers to middleman and skim. Ironic that the EU is the true prize here – a billion or so very sophisticated consumers. Didn’t we just tell them to stuff it? Ha. Which might explain our distress over Russian oil being retailed, direct from the factory. Can’t have that. Too authoritarian.

Really nice piece Connor.

Although I’m sure you have no shortage of ideas for future material, I had the thought while reading this that maybe you could do a future article or a series of articles detailing the major pipelines around the world, including maps and diagrams to give a good picture.

These things are talked about a lot but usually only in the context of a single pipeline. It would be nice to see the larger picture including who is moving what where.

Conor, really fine essay.

Also, notice that President Putin is now in Azerbaijan on an official visit.

Possibly because Astana sits on the Iranian border and Azerbaijan is armed by Israel.

It was from Azerbaijan that Iranian President Raisi flew home on his death flight

After a longer comment went poof (c’est la vie) I’ll just say that I was for a time acquainted with and did work for Armenian Americans in NYC in the years after 9-11. Twenty years later, these then wealthy and influential folks have certainly embedded themselves in the current Armenian government and their interests are aligned with the rules based order and not the ordinary citizens. “Same as it ever was…….” YMMV, of course.

Adding, superb essay and analysis, Conor!

So, Kardashians won’t save Armenian Armenians.

Joys of Imperial Overreach

US entered war in 1917 to get a seat at the table and FDR manipulated to get control of British Empire after Dawes took control of Germany in 1924 before evolving into Vice President

Now it is global control that is the objective

You just need to glance at the map in the article to see why this is a ridiculous strategy. It’s analogous to Russia or China having a strategy to keep the US out of the Gulf of Mexico.

As usual, the US accuses others of that which it is doing. Russia and China do not demand such a high price, or subservience.

Speaking about malign influence, Russia and China do not disperse depleted uranium all over your land and then tell you that increased cancer rates are just your imagination.

It’s hard to imagine that supposed diplomats would make such a statement. There is nothing on offer.

The US, to itself, “hold my beer” as it pushes China and India together through its machinations in Bangladesh.