By Lambert Strether of Corrente

This is Naked Capitalism fundraising week. 201 donors have already invested in our efforts to combat corruption and predatory conduct, particularly in the financial realm. Please join us and participate via our donation page, which shows how to give via check, credit card, debit card, PayPal, Clover, or Wise. Read about why we’re doing this fundraiser, what we’ve accomplished in the last year, and our current goal, strengthening our IT infrastructure.

Everyone you meet is fighting a battle you know nothing about. Be kind. Always. –Apocryphal, attributed to Robin Williams

This week is a very serious week at Naked Capitalism, so I thought I would switch things up and present you, readers, with an amuse-bouche, the sort of old school blogging post where I start out not knowing where I will end up.

Not to knock my mother’s cooking, but it was American-style from women’s magazines in the 1950s (meatloaf, creamed peas, jello): well-planned, nutritious, even, but not cuisine. I learned to eat late in life, in my mid-30s, in Montreal, where I had come for a TeX conference at McGill — I was a desktop publisher several careers ago — and when the program had ended for the day, I walked down the Mountain toward Ste Catherine’s street, and wandered into a random steakhouse, because I thought I would treat myself.

The steakhouse was the Alouette Steak House. The warm room was full of solid provincial bourgeoisie, tucking in. From the menu — exotically in both French (large type) and English (small type) — I selected steak au poivre with frites, escargot for an apetizer, and a carafe of red wine (considering the room, “I’ll have what they’re having”). The air outside was crisp; inside, the windows were steamy. The plump chef, in his white toque, seared the steaks on a rotating grill, presumbly for speed. The bread, wine, and the escargot arrived; I had never encountered a plate with hemispherical convexities to hold snails, which were garlicky, soaked in oil, and could not quite be said to be tough. I polished them off, soaked up the garlic and oil with the bread, and cut the oil and the garlic with a gulp of wine. The steak arrived, crusted with peppercorns, slathered in cream sauce. I sawed off a hunk….

My whole mouth was happy. My whole body was happy. I don’t know why this never happened before, but it did. As you can see, this was a madeleine moment for me. Bourdain is an actual food writer, unlike me and far better, and here is his madeleine moment, which happened to him when he was much younger than I was then. From Kitchen Confidential (2000), pp. 18-19:

We’d already polished off the Brie and baguettes and downed the Evian, but I was still hungry, and characteristically said so. Monsieur Saint-Jour, on hearing this-as if challenging his American passengers-inquired in his thick Girondais accent, if any of us would care to try an oyster.

My parents hesitated. I doubt they’d realized they might have actually to eat one of the raw, slimy things we were currently floating over. My little brother recoiled in horror.

But I, in the proudest moment of my young life, stood up smartly, grinning with defiance, and volunteered to be the first.

And in that unforgettably sweet moment in my personal history, that one moment still more alive for me than so many of the other ‘firsts’ which followed—first joint, first day in high school, first published book, or any other thing—I attained glory. Monsieur Saint-Jour beckoned me over to the gunwale, where he leaned over, reached down until his head nearly disappeared underwater, and emerged holding a single silt-encrusted oyster, huge and irregularly shaped, in his rough, clawlike fist. With a snubby, rust-covered oyster knife, he popped the thing open and handed it to me, everyone watching now, my little brother shrinking away from this glistening, vaguely sexual-looking object, still dripping and nearly alive.

I took it in my hand, tilted the shell back into my mouth as instructed by the by now beaming Monsieur Saint-Jour, and with one bite and a slurp, wolfed it down. It tasted of seawater . . . of brine and flesh . . . and somehow . . . of the future.

Everything was different now. Everything.

I’d not only survived—I’d enjoyed.

This, I knew, was the magic I had until now been only dimly and spitefully aware of. I was hooked. My parents’ shudders, my little brother’s expression of unrestrained revulsion and amazement only reinforced the sense that I had, somehow, become a man. I had had an adventure, tasted forbidden fruit, and everything that followed in my life-the food, the long and often stupid and self-destructive chase for the next thing, whether it was drugs or sex or some other new sensation-would all stem from this moment.

I’d learned something. Viscerally, instinctively, spiritually—even in some small, precursive way, sexually—and there was no turning back. The genie was out of the bottle. My life as a cook, and as a chef, had begun.

Food had power.

It could inspire, astonish, shock, excite, delight and impress. It had the power to please me . . . and others. This was valuable information.

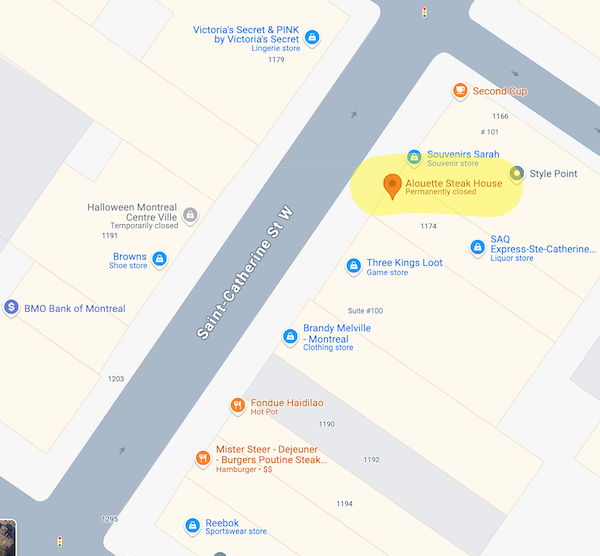

I was dining in solitary splendor, and so experienced the aesthetics only; not power, as did Bourdain (for good or ill). Sadly, the Alouette Steak House is gone now:

Gone like so much else downtown. I moved on to much more upscale eateries, though I do not think at that time celebrity chefs were a thing; everything was still innocent, still about the food. I discovered tasting menus, seven courses of tiny delicious morsels, and menus that specified ingredients like “Monsieur Fortier’s greens,” which was great, because local! I was supporting a farm! (In fact, one of the best meals I ever ate was in my home town in Maine, where the cook created a Slow Food dinner, all from local ingredients (so any town can do it)). I also learned to deprecate the American practice of surrounding a great slab of meat with sides; at that time, in Montreal at least, meat and vegetables were equally important on the plate, and designed to complement and reinforce each other.

On reflection, rereading my own experience in Montreal, I see that with “the bread… arrived,” I have fetishized the bread and made it into an active agent; in fact, a serveur brought me my food. Bringing us to one of many Bourdain reflections on staff. Again from Kitchen Confidential, pp 208-209:

I guess it was a historic moment.

[Steven] showed up looking for a sauté position, his even more degenerate friend Adam Real-Last- Name-Unknown in tow….

When Steven and Adam were in the kitchen together, I couldn’t turn my back for a second. They were hyperactive and destructive, two evil Energizer bunnies who, when they weren’t squabbling and throwing food at each other, seemed always to be dodging out of the kitchen on various criminal errands. They were loud, larcenous, relentlessly curious—Steven can’t look at a desk without rifling its contents; they played practical jokes, and set up whole networks of like-minded co-workers. A few weeks after he arrived, Steven already had the whole club wired from top to bottom: the office help would tell him what everyone else was getting paid, security would give him a cut of whatever drugs they impounded at the door, and the techies let him play with the computers…. Maintenance gave him a share of the lost-and-found and split the leftover booty from the promotional events-goody bags filled with cosmetics, CDs, T-shirts, bomber jackets, wrist- watches, etc.; the chief of maintenance even gave Steven the key to a disused office on the Supper Club’s neglected third floor, an old janitor’s storage room that, unbeknownst to management, had been converted to a carpeted, furnished and fully decorated pleasure pit, complete with working phone. It was a space suitable for small gatherings, drug deals and empire-building. [The room] had been done up with pilfered carpet remnants and furniture from the adjoining Edison Hotel. As the space was located up a long flight of garbage-strewn back stairs, behind the reeking locker-rooms, down a dark, unlit hall where spare china was stored, management never visited—and a young man could be secure in the knowledge that whatever dark business he was conducting, no matter how loud, unruly or felonious, he was unlikely to be disturbed.

The boy could cook, though.

The sort of delicious office politics I learned at my father’s knee…

Kitchen Confidential made Bourdain into a celebrity and then a TV star, but I’m going to skip over all that and present three short video clips that show how much he loved food (and delicious food that locals could eat, for not much money, unlike my excessive and precious tasting menus). From San Francisco, the Swan Oyster House:

“All that good stuff. Brains, and fat….”

From Camden, New Jersey, Donkey’s place:

Bourdain’s “Really!” after learning this cheese steak is served on a Kaiser roll is priceless.

From Vietnam, a food cart:

“All the things I need for happiness.”

I think a common factor in all these videos is Bourdain’s respect for the people who made the food, which infuses Kitchen Confidential, despite the bravura Hunter Thompson-eque passage I quoted on office politics. Let me quote Chris Arnade, who in his columns (and book) on walking the world, here seems to follow the master, Bourdain:

While walking for two weeks in Lima, I ate a lot of ceviche, and drank a lot of Pilsen Callao (sorry, Pilsen is better than the better known Cusqueña, and cheaper).

Because everyone in Lima is hustling, since the city hasn’t been taken over by franchises, you can eat from hundreds of places, each a little different. Stands, stalls, carts, and store fronts all serve food, all made that day, or the night before.

Franchising lowers the risk of what you eat, but by lowering quality. While you know what you are going to get, it will be pretty mediocre.

It also destroys the transcendent. To steal from Walter Benjamin and his “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” getting your hamburger put together in minutes from a chain removes any aura around making and eating food.

That isn’t the case when you are one foot away from three women making ceviche with fish from two fish sellers a stall over.

All of whom get immense pride out of doing it. The dignity of work is an overused phrase, but the meaning that comes from making something special, even if it is “only” ceviche, or Aguadito De Pollo, is a real thing.

So I prefer taking the gamble of having a few bad moments, to find the truly sublime, and in a tiny way, capture part of that aura. I also prefer giving my money to the people doing the creation.

I am sure Bourdain would agree with this, as do I!

I was wrong in the lead. We all know where we will end up, later, one hopes, rather than sooner. Sadly, Anthony Bourdain took his own life, strange for someone who was so full of life (especially when eating, as the videos show). Celebrity is bad for people; wealth is bad for people; but we do not and cannot know what internal battle Bourdain was fighting, no matter how much through gossip we attempt to anatomize the mysterious (most things in life that are important being mysterious, after all). With James’s Lambert Strether I would say: “Live all you can. It’s a mistake not to.” So eat as well as you can, respect the workers who create the food you eat, and try to be kind.

APPENDIX Seafood Stew

Since this clip is famous, here is Bourdain over-simplifying Collaterized Debt Obligations (CDOs) in The Big Short. Horrid book, horrifying movie (at least to a financial layperson):

For the straight dope on CDOs, see Yves here in 2010 for the correct technical explanation from an expert. That said, “It’s not old fish, it’s a whole new thing! And the best part is they’re eating three day-old halibut” does seem to apply in our financialized economy, and not just to financial products. One might consider AI training sets to be a seafood stew, for example.

Great book, even though he is celebrating the more problematic elements of the culture most of the time. As he notes near the end of the book, it’s not the only way to do it, but it wasn’t until later in life that he started to explore some of those for himself. He was unquestionably a great writer and storyteller and I think it was that, even more than his culinary skills, that set the groundwork for his later career.

You don’t mention it except for a brief reference at the end, but he had a lot to say on common NC topics as well. On the opioid crisis, from GQ:

From Vivien Sansour at Electronic Intifada on his visit to Palestine:

Right now I am reading this at the Public Library. When I have access to a workplace computer with speakers ( on break or other offtime/downtime) I will watch-hear the videos.

( Parenthetically, ” Not to knock my mother’s cooking, but it was American-style from women’s magazines in the 1950s (meatloaf, creamed peas, jello): well-planned, nutritious, even, but not cuisine.) ” . . . signposts the culinary and cultural disaster which overtook American cooking and culture during our hyper-industrialization and hyper-urbanization period. Before the forced emergence of American-style from women’s magazines in the 1950s type food, America had a cuisine, or maybe several cuisines. They were all suppressed and driven to the back of scattered dark caves. Karen Hess and John L. Hess wrote a book about that called The Taste of America. Here is what appears to be a teaser e-version of that very book, readable page by page if you create a ” free account”.

https://archive.org/details/tasteofamerica0000hess_z9q4 )

Thank you for this fine essay on food, and the joy that it should inspire, and the gratitude we should all have for those who provide and prepare it. But also for the reminder – I am saying this as someone with 40+ years in radio and tv news – that Bourdain was the best broadcast journalist in the U.S. Until he was gone.

Thanks for the great vignette Lambert!

Bourdain was a culinary cultural-anthropologist, who had a wonderful respect for all of the people in the countries he visited. Moreover, he had the best, hands-down, take down of Henry Kissinger. “Once you’ve been to Cambodia, you’ll never stop wanting to beat Henry Kissinger to death with your bare hands.”

Nice. That’s very good.

👍👍👍

Indeed a great quote.

Thank you!

The dramatized Kitchen Confidential may be worth the brilliance of that storyhttps://archive.org/details/kitchen-confidential-omnibus

15 years ago, Vienna.

We had reserved a table at a great place in the students´ part of town, not too far from the Opera.

The place served (and still does I hope) what we call “Hausmannskost”, which means e.g. innards in various forms, such as lung, liver, heart, tongue, maw etc.

When we arrived the tiny place located on two floors in a derelict 19th century apartment house was packed.

We could barely get to our table.

And then we…waited.

About an hour. Quite exasperated: What the hell was going on.

People from all over the world were there virtually descending upon their plates.

Especially Americans. The kind you would not expect at such a special location, normally.

We had heard it´s popular – but with native Viennese. Not tourists.

Eventually our waitress showed up.

Completely overwhelmed. Almost crying. Apologizing.

She stated that they were simply too few waiters. But how so?

It´s a known place. But this? And the Americans above all. They were ordering entire menues.

But where did they come from? The waitress didn´t even speak English, she complained.

We asked her why these tourists had shown up so unexpectedly? So many? She didn´t know.

The only info she had picked up at some table was that some of the Americans were talking about a guy who had recommended their venue on some TV show.

A food critic? A journalist? Who? She didn´t know. But someone with an odd name – Bourdain?

Ever heard of him?

Well that explained it.

Bourdain had visited the place a couple of days before and what followed was a ravishing review on his show and EVERY single tourist in Vienna that week had seen it.

Another nice episode of his was when Bourdain met party leader Gregor Gysi of German The Left Party.

Gysi invited Bourdain to his favourite place in the Berlin suburb of Köpenick to eat Eisbein.

And I tell you what: During that 45 min. episode between Bourdain and Gregor Gysi you could learn more about Mr. Gysi than in any number of newspaper op-eds that would explain why he had so utterly failed in his leadership of DIE LINKE.

Watching that encounter made the demise of the party and the split of BSW everything but a suprise!

He even surpassed Bourdain in his drive to impress, to dominate, to tell the audience what to think and what to say. He almost wanted to cut the meat FOR Bourdain and feed it to him.

Bourdain being an entertainer had no pressure.

Gysi – only.

p.s. I respect Gysi for what he accomplished and he didn´t have an easy time in the 1990s. But he has some serious personality issues. Or as my former professor used to say: You learn to know people during meals.

Thank you!

Delightful meditation on the power of food. Living as I do in the region where Slow Food was founded, has an enormous influence, and is still headquartered (in the nearby town of Bra), I am glad for the mention of Slow Food and its stress on ingredients.

(Slow Food as a gastronomic society has come in for criticism, because it is a departure from its mission, as a friend of mine, a former long-time employee, reminds me.)

First: Fetishizing bread. One must fetishize bread. Here in Italy, bread is a daily food, a foundation of life, and is made with great care and handled with great care. Italians are fussy about bread. U.S.ians have trouble with bread because the grain is mishandled and the flour is adulterated. Fussy Italians produce flour that behaves considerably differently from what I knew in the U S of A.

So: Bread and wine. There’s a reason for those sacred foods (in Catholicism, Orthodoxy, and the Churches of the East).

I can’t call it a madeleine moment, but I had an aha! moment not long after my arrival in the Chocolate City when I noticed how much of Italian life centers on growing, delivery, and production of food. The infrastructure starts there.

And now I am off to the open-air marked in Via Maria Cristina because the “mercato dei contadini” (local farmers) will present me with purslane, dandelion, catalogna (domesticated dandelion), rucola / rocket, and the many different kinds of potatoes. As a gourmand, one must start with something humble like potatoes. The rest is built on bread and potatoes, eh.

Bread, cheese, prosciutto di Parma (or better, Iberian ham from acorn-fed pigs)… and a wonderful red.

An easy way to feel the same as Bourdain did having an oyster. May be not Slow Food in the kitchen but one has admire the slow motion creation of all those wonders. Some magic is done outside the kitchen.

> catalogna

Orwell was a foodie, then.

Ha! But as far as dining venues he was also Down and Out in Paris and London.

Hi nakedcapitalism.com admin, You always provide practical solutions and recommendations.

I read the book when it came out while working in the restaurant industry myself at the time. I can vouch for the fact that everything he talks about happening behind the scenes that diners would not want to know about is 100% true!

And thank for the excerpts – I’d forgotten what a great writer he was.

I’ve been watching his shows the last while, on in the background while making food in the kitchen :)

The older ones are all worth a look: A Cook’s Tour, No Reservations (on this now), and later The Layover then Parts Unknown.

Recommend hunting them out (the online ‘high seas’ may be the easiest place), great for watching in the background.

I think his death is one that will never make full sense to anyone – and that if he had decided to sleep on it instead, the idea may not have made sense to him either the morning after – but it’s great to (belatedly) enjoy his shows and appreciate his character, even if the occasional mocking descriptions of how he’d rather top himself than eat a particular meal again, end up a bit too close to reality!

I too can remember my ah-hah! food epiphany. I was about 12 years old and for some reason my parents had decided to visit Victoria BC. They took me to dinner at a fine-dining restaurant on the way to a theatrical performance of Androcles and the Lion and goaded me into ordering escargots as an hors d’oeuvre. I can still remember the bleached shells nestled in their little divots swimming in glistening garlic butter flecked with parsley, and the explosion of flavor in my mouth. When I could finally drive on my own I’d frequently make the 90-minute trip to eat upstairs at the Café at Chez Panisse (never the fancy downstairs). I loved when I managed to be seated at one of the little tables in the glassy nook above the wisteria arbor.

Anthony Bourdain did us all a favor by opening-up the world of chain-smoking addicts and obsessives working the stoves behind the scenes. He democratized fine dining and multi-culturalism in a way that elevated the quality of the experience for his readers (and later viewers) while encouraging restaurants to take better care of their workers.

Bourdain gave the world an incredible gift, but hearing his name now fills me with sadness. I was once fortunate to hear him present a more genuine version of himself at a book-signing. I found his untimely demise to be a cautionary tale about our culture of celebrity and obsessively counting coup on social media.

> divot

Damn. That was the word I was looking for.

On a pretty tangentially related note, I’m curious if anyone has more information on the progressive reduction in admission standards for the British Army during the period when food began to be canned and preserved on a large scale, enabling it to be stored for longer periods and shipped longer distances, with a concomitant decline in nutritional quality compared with food grown and consumed locally, as it had been throughout history up to that point. I’m not even sure of the exact time frame, but maybe early to mid 19th century?

(A tangent to my tangent is the hypothesis that exposed lead welds in the tins of canned food procured for the doomed 1845 Franklin expedition gave the sailors lead poisoning and led to their deaths – an explanation that has however lately been challenged…)

During this time the height standards for army recruits apparently had to be progressively lowered over a period of decades as the physical quality of candidates deteriorated, while at the same time their counterparts in Australia – the descendants of the convicts originally shipped there – steadily outstripped them in height, strength and general good health. I heard about this several years ago but forgot to note the source. Anyone have anything to add – or correct? TIA.

Where food and permaculture overlap . . . this new avocado development from Australia might be of interest to the food forest community . . .

https://www.reddit.com/r/Damnthatsinteresting/comments/1fb0274/an_australian_gardener_after_30_years_of_trying/

And that ” an Australian gardener” did it is a testament to citizen science . . . in this case citizen plant breeding.