This is Naked Capitalism fundraising week. 783 donors have already invested in our efforts to combat corruption and predatory conduct, particularly in the financial realm. Please join us and participate via our donation page, which shows how to give via check, credit card, debit card, PayPal, Clover, or Wise. Read about why we’re doing this fundraiser, what we’ve accomplished in the last year, and our current goal, karōshi prevention.

Yves here. I imagine readers will take issue with this post, analytically and practically. Let’s start out with the lack of authority economists have to discuss climate change analyses, given their acceptance of the destructive work of William Nordhaus, appallingly legitimated by giving him a Nobel Prize. The authors are on extremely thin ice in criticizing the caliber of degrowth studies in light of how they’ve celebrated appalling poor studies that fit their preferences. Steve Keen is good one-stop shopping for an evisceration of his claims.

This article pointedly ignores the lack of any solutions to our accelerating climate change crisis that are remotely adequate to the scale of the problem. It also takes the position that the needs of the economy take precedence over the future of the biosphere and the intermediate -term survival of something dimly representing modern civilization (we are likely past that being an achievable outcome, but it should at least be acknowledged as an aim). And it also implicitly ignores that absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.

By Ivan Savin and Jeroen van den Bergh. Originally published at VoxEU

In the last decade, many publications have appeared on degrowth as a strategy to confront environmental and social problems. This column reviews their content, data, and methods. The authors conclude that a large majority of the studies are opinions rather than analysis, few studies use quantitative or qualitative data, and even fewer use formal modelling; the first and second type tend to include small samples or focus on non-representative cases; most studies offer ad hoc and subjective policy advice, lacking policy evaluation and integration with insights from the literature on environmental/climate policies; and of the few studies on public support, a majority and the most solid ones conclude that degrowth strategies and policies are socially and politically infeasible.

In the last decade, numerous studies have been published in scientific journals that propose the strategy of ‘degrowth’, as an alternative to green growth (Tréquer et al. 2012, Tol and Lyons 2012, Aghion 2023). The notion of degrowth refers to reducing the size of the economy to confront environmental and social problems. While having little academic stance (yet), the topic is receiving quite some attention in the media and the public sphere in general. Witness two conferences organised in the European Parliament.

To assess the scientific quality of degrowth thinking, we conducted a systematic literature review of 561 published studies using the term in their title (Savin and van den Bergh 2024). This allowed us to determine the share of studies offering conceptual discussion and subjective opinions versus data analysis or quantitative modelling. In addition, we examined if studies addressed climate/environmental policy, including policy support/feasibility, and whether this was well embedded in the broader literature on this.

Distribution of Studies Over Time, Countries, and Presence of Scientific Methods

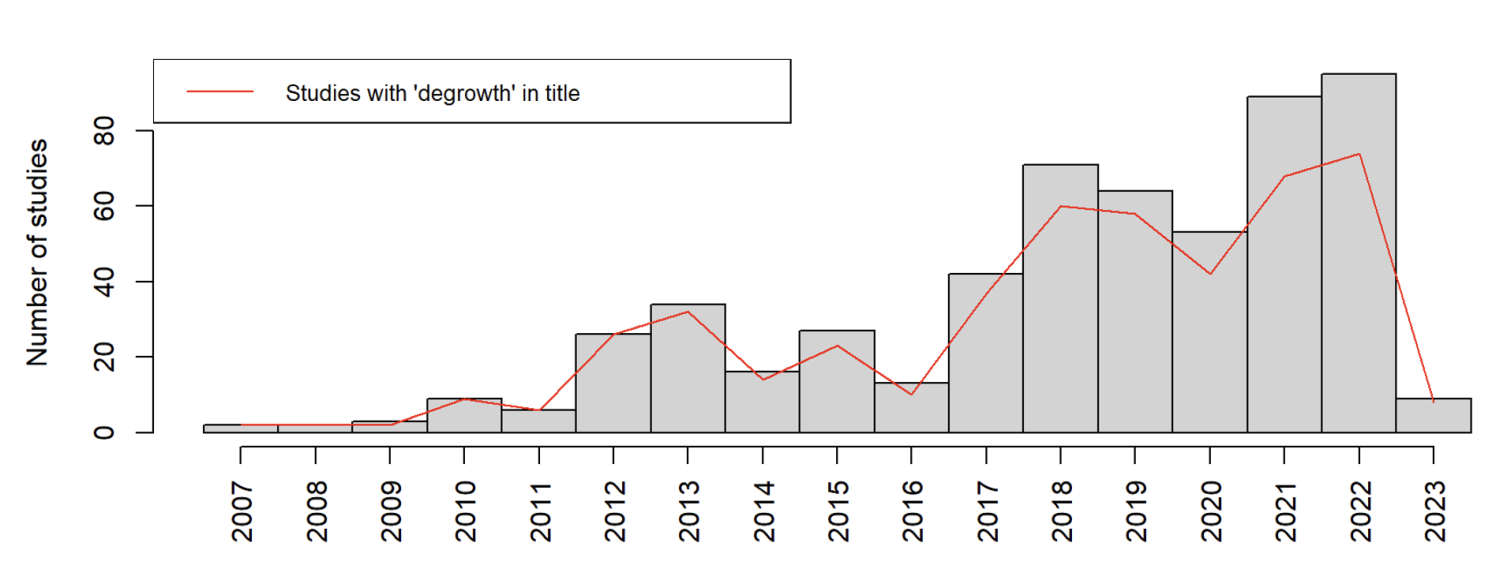

Figure 1 shows a growing number of studies on degrowth over time. As indicated by the red line, ten years ago virtually all studies in this vein explicitly mentioned the term “degrowth” in their title, while more recently many use the vaguer term “postgrowth” instead, possibly to reduce resistance.

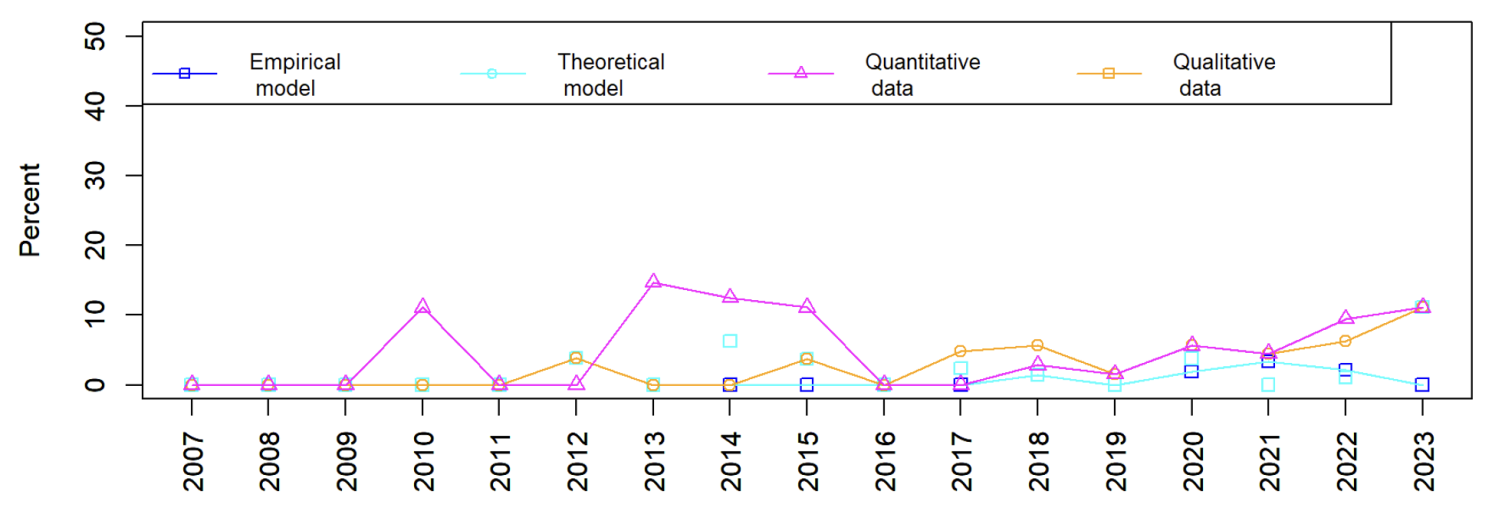

The large majority (almost 90%) of studies are opinions rather than analysis. Only nine studies (1.6% of the sample) use a theoretical model, eight (1.4%) employed an empirical model, 31 (5.5%) performed quantitative data analysis, and another 23 studies (4.1%) qualitative data analysis (e.g. interviews). As Figure 3 shows, there is no clear trend indicating that the share of studies with a concrete method is increasing.

Figure 1 Time distribution of academic publications on degrowth

Note: The histogram depicts the frequency of studies by year while the red line indicates the number of studies that used “degrowth” (as opposed to post-growth) in their title.

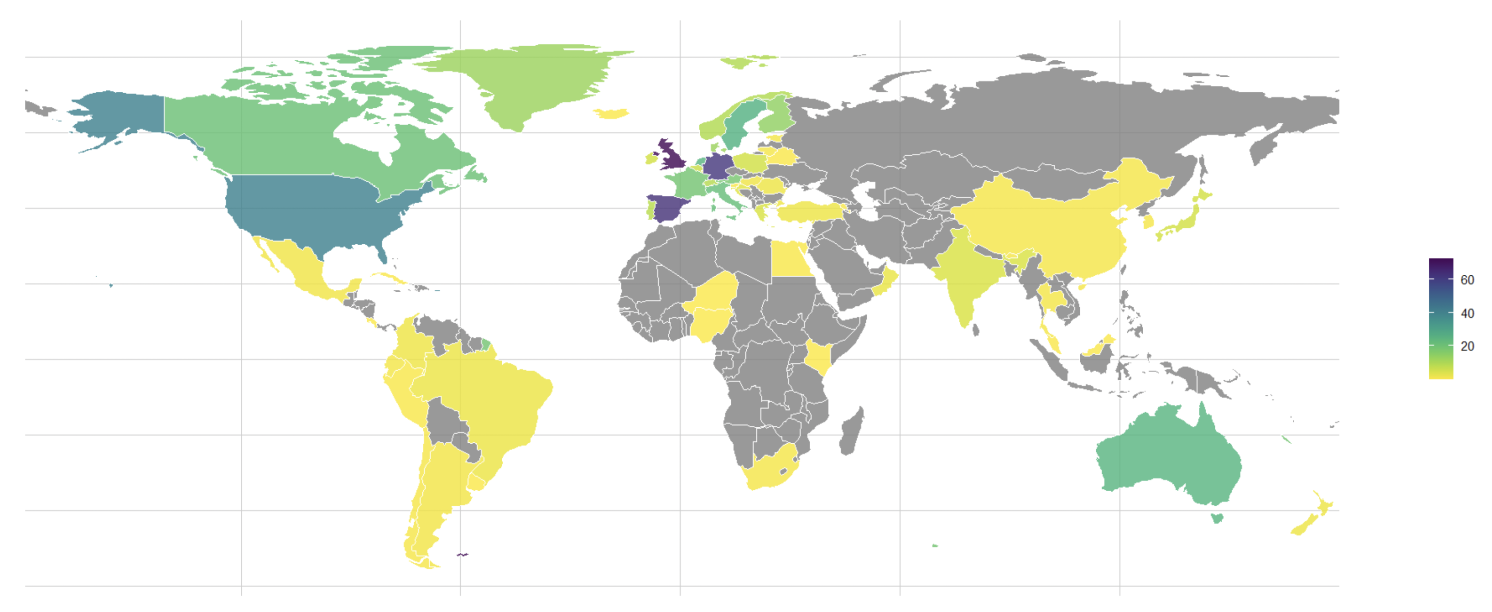

Most authors in the sample are affiliated with institutes in Western Europe and the US (Figure 2), with the UK, Spain, and Germany leading by a large margin. This is in line with earlier research finding that there is little support for degrowth in the Global South (King et al. 2023).

Figure 2 Geographical frequency of author affiliations

Figure 3 The time pattern of the share of studies using one of the four methods

Focus on Small Samples and Lack of Systemic Perspective on the Economy

Inspecting the 54 studies that used qualitative or quantitative data analysis, we find that they tend to include small samples or focus on peculiar cases – for example, ten interviews with 11 respondents on the topic of local growth discourses in the small town of Alingsås, Sweden (Buhr et al. 2018), or two locations of ‘rural-urban (rurban) squatting’ in the Barcelona hills of Collserola (Cattaneo and Gavaldà 2010). This easily gives rise to non-representative or even biased insights. This weakness of empirical research on degrowth is understandable to some extent. The idea of degrowth is so far from reality and has seen no serious implementation, which makes good empirical studies a challenging task. Past experiences as in communist countries (e.g. Cuba), low-growth countries (e.g. Japan), or economic decline due to COVID-19 do not serve as convincing examples of degrowth. Arguably the best one can achieve is stated-preference research and behavioural experiments. Whereas this should then be done for sufficiently large samples, this ambition tends to be lacking in studies on degrowth. The few studies that do use larger data sets tend to not collect these themselves but rely on data of a general nature, such as the European Value Study (Paulson and Büchs 2022). The problem is that these do not explicitly inquire about degrowth but pose rather general questions about growth versus environment which are open to interpretation (Drews et al. 2018). As a result, the associated studies arrive at overly optimistic conclusions about support for degrowth (Paulson and Büchs 2022). This is confirmed by several solid studies by psychologists which find that most participants in experiments tend to emotionally react negatively to a message of advocating radical degrowth, while many perceive degrowth strategies as a threat. In addition, earlier surveys which try to clearly separate the distinct positions on growth versus environment (like by Drews et al. 2019) find more support for ‘agrowth’, i.e. being agnostic about or ignoring GDP (van den Bergh, 2011), than degrowth among academic researchers broadly as well as the general public.

Since degrowth strategies tend to be radical, i.e. they propose major changes in socioeconomic systems, it is crucial to have good insight into their systemic and macroeconomic consequences. But unfortunately, many studies propose to undertake a large socioeconomic experiment with big socioeconomic risks without having insight into the bigger picture. Most quantitative and qualitative studies focus on small and local issues, usually with non-representative and very small samples – making it impossible to draw conclusions about the systemic impacts. Out of the 561 studies we reviewed, only 17 studies using theoretical or empirical modelling shed some light on these broader consequences. Several of them draw rather pessimistic conclusions in this regard. For example, Hardt et al. (2020) find that a shift towards labour-intensive service sectors – part of many degrowth proposals – would result in small reductions in overall energy use because of their indirect energy use. And Malmaeus et al. (2020) conclude that universal basic income, a popular theme in degrowth writings, is less compatible with a local, labour-intensive and self-sufficient economy than with a global, capital-intensive and high-tech economy.

It is worthwhile noting that a lot of research that goes under the label of ‘degrowth’ is not original but comes down to relabelling existing research, such as on worktime reduction, circular economy, refurbishing houses, or the bioeconomy. This is ironic given the plea for ‘decolonising’ in the degrowth community (Deschner and Hurst 2018).

Why So Many Bad Studies and the Need for Self-Criticism?

One may wonder how it is possible that so many degrowth studies of inferior quality got published. One explanation is that around 100 articles in our sample were published in special issues (14 in total) while another 18 were published by the Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI), which has been accused of being a predatory publisher (Ángeles Oviedo-García 2021). Another possible explanation is that many reviewers are selected based on their sympathy for degrowth (indicated by past publications promoting it) instead of shown expertise regarding application of methods. Altogether, the journal review process to judge papers was likely more lenient for many degrowth studies than for the average academic article. As a consequence, published research on degrowth is dominated by ideology while lacking scientific quality.

Through drawing attention to several weaknesses in the way research on degrowth is undertaken, our review suggests the need for a healthy degree of self-criticism and modesty in the degrowth community. The research should become more ambitious in terms of case study selection to assure that local- or region-scale studies are complementary and representative. In turn, this will allow for generalisation or upscaling of findings to arrive at a credible global picture. To further contribute to this goal, also more studies are needed of a systemic nature – to assess the relative role of scale versus substitution and efficiency as well as to determine indirect economic, social, and environmental effects, notably energy/carbon rebound. Next, for degrowth research to be taken more seriously, it is essential that it sets higher standards for size and representativeness of samples in empirical studies, investigates public and stakeholder support of degrowth thinking, and strives for synergy with existing research fields (e.g. economics, psychology, policy studies) as these offer a wealth of insights about designing effective, efficient, and equitable environmental/climate policy that can count on sufficient public support.

See original post for references

One wonders where the authors would propose obtaining the empirical data necessary for good quantitative anaysis and modeling. Gaza?

Yeeeeeowch!? Or retired working-class Americans relying solely on Social Security?

I just grabbed this from todays NC links… seems germane to degrowf.

A Personal Meditation on Growing Old Rebecca Gordon, TomDispatch

https://tomdispatch.com/a-personal-meditation-on-growing-old/

I don’t consider that either ‘green growth’ or ‘degrowth’ are valid analytical categories.

Like all such concepts which directly or indirectly arise from economics, they rely on an underlying assumption of the commensurability of the variables used, which implicitly in this case is GDP, which in turn is measured by money.

There is in fact no evidence whatever that environmental values are commensurate, at least when measured by way of how people value them. There is a vast literature on assessing the commensurability of intangible ‘values’ such as landscape, pollution, amenity, ecology, etc, and it all points to weak, or non-existent commensurability. This of course is ignored by the wider economics community, because it means their tools of analysis have little to no substance to add to the discussion.

When addressing environmental harms, most impacts are to some degree intangible (such as the perception of degradation of a landscape, or the loss of species from a woodland), or require different forms of assessment – such as increasing the hypothetical but unpredictable flooding impact. Our tools for assessing these are very crude – not through want of trying, its just a reality that its very hard to put a concrete ‘value’ on them. Even defining ‘value’ in a meaningful way is extremely difficult.

To give a hypothetical example, lets imagine two equal sized and equally prosperous countries, A and B, both with similar resource and population bases.

Both countries have, for cultural and historical reasons, very different economic policies.

Country A has long pursued a policy of focusing on domestic resources. Its agricultural policy is based on incentivising farmers to produce a wide range of products with the use of minimal imported fertilisers and chemicals, including those which could probably be imported more cheaply. Its transport policy has long focused on spending 80% of its budget on rail and bus services, and to facilitate this encourages high density urban areas and has generally banned low density housing in rural areas. It has a tourism policy based on providing lots of all year round facilities for domestic tourists to encourage people to stay local. Its energy policy has focused on developing domestic energy reserves, even though this raises prices – it is justified through the need to ensure resilience and energy security.

Country B has a policy of efficiency and openness to its neighbours. Its agriculture policy focuses on its most productive products and it incentivises value added exports, while importing non-seasonal goods. Lower productive farmland is allowed to regenerate for nature. It has a roads focused transport policy, and it allows easy self building and low density suburbs on low productivity land in order to make housing cheaper. It has built a major airport to encourage more tourists to visit. Its energy policy is based on large, efficient thermal plants to push down the price of electricity and energy for everyone.

Which country is most environmentally and socially damaging? Which one is most ‘pro-growth’ or pro-degrowth?

I don’t consider that the ‘growth’ or ‘degrowth’ categories have any analytical value. What matters is our wider choices and their impacts. These may be tied to measures of GDP growth, but equally (as even Keynes pointed out in his famous hole digging analogy), may have absolutely nothing to do with GDP. You can have a rapidly declining economy with massive environmental damage, or a relatively benign form of growth. We need to focus on the real world impact of human activities, and not get distracted by the type of category errors economists love adding to public discourse.

My thoughts exactly, although my thoughts would have been much more jumbled! The key to avoiding the worst of the coming jackpot is to live with less. This does not mean living meanly, however. But it will require adjustments. Herman Daly began writing about this as early as 1972, probably earlier. He did not dwell in the land of category errors that is conventional economics. This is really not that complicated.

GDP is a terrible metric even if you want to measure the economy:

– It lacks a robust way to measure the size of the service economy.

– For some insane reason it includes banking and insurance.

– It presents the costs of ‘growth’ equally with the benefits. For example, if you build a mine, the costs of developing that mine are included as part of GDP. The more inefficient that development process, the higher the GDP.

The metrics that truly count are our inputs (energy and non-renewable commodities) and externalities (e.g. pollution). We should identify what the sustainable values are, and then design a society/structure that can exist within them. That’s not easy, but it’s more useful than focusing on GDP ‘growth’.

It also requires taking a systems approach. E.g., electricity (no matter how it’s generated) cannot substitute for many of the ways that we use oil/gas/coal today. Energy is not a fungible resource. This means that many of the ways that our society are structured (relating to food systems, urban systems, trade, heavy industry, construction, transport and mining) will be impossible. Even if we ignore CO2 (unwise), our use of fossil fuels will decline as they become harder/more expensive (in terms of energy) to acquire. Hubbert’s Peak comes for all of us eventually.

Exactly. Personally, I have strong suspicion that “degrowth” is just a codeword for taking from the less well off so that the well off can feel better about themselves, or “degrowth for you, not me” type scam. Perhaps I’m not being fair, but a lack of analytical value certainly helps advance that kind of abuse.

So if I got this right, they did not do an actual assessment of degrowth but only papers that had that term in their titles. In it’s tone, it sounds like more of a hit piece and in this article they were really pulling a long bow trying to attack them as a group and ended up fobbing them off by saying that more study was needed. Isn’t that what the tobacco industry said back in the 70s? The thing is degrowth will be like the falling of the leaves in the autumn. It will be a natural process, especially in light of the fact that resource depletion is a thing and cannot be ignored. Attempts to collect those leaves and try to glue them back on or climbing on ladders to pull those leaves off quicker will not make a difference in the long run. We have had a few centuries of growth but have now outstripped the planet’s capability to support that much more. So now we are near the top about to head down the reverse slope. In the meantime, I expect these two authors to come up with another study saying that yes, trees can in fact grow to the sky.

It’s also kind of funny to hear economists say other people should have humility given how godawful much of their research/theory is. For example, economists theory of resource depletion assumes many things that are never true in the real world, does not match up to the historical record and also makes assumptions about how mining companies think which would be quickly dispelled if they ever talked to anyone who works in that industry.

Once more with feeling!

Economics is not a science, and economists are not even close to being scientists.

And the economics award is an award from the Swedish Royal Bank. They do not call it a “Nobel Prize” as it has no relationship to Nobel’s Will and was only created by the Bank in 1967.

Exactly, this line was marvelous in its transparent projection:

“ our review suggests the need for a healthy degree of self-criticism and modesty in the degrowth community”

From economists…

PS that Rijksbank prize should have an asterisk if it is referred to using the dynamite inventor’s name.

I’ve stopped getting mad or otherwise engaging with obvious propaganda like this.

The “wise apes” will only learn after Mother Nature shows them the consequences, like the petulant children they are.

Sorry I don’t have the link, but within the last couple days, I read an article about an astronaut who spent half a year in space and came away convinced that we’ve been brain-washed into believing that prioritizing the economy front and center in all our thinking is foolishness.

He said that looking down from space, at the very thin layer of air and water that we share with the whole planet, made it obvious that our priorities are misplaced.

This post is simply an example of the constant stream of BS necessary to maintaining the false notion that allowing the rich to do what they will is best for all of us.

Various links here, I think.

Here is the link. Great article… nice dot connect. Jill stein 2024?

https://en.interaffairs.ru/article/we-re-living-a-lie-astronaut-reveals-shock-realization-after-viewing-earth-from-space/

Here is Jill Stein’s post debate platform discussion. First six minutes are zoom call issue-laden…

https://youtu.be/ftL8uv74q-k?t=358

I have problems with the field of degrowth. They’re imprecise with their definitions (yes GDP is hugely flawed, but then what do you mean by growth), and the focus on economics seems misplaced. Surely the problem is with consumption of resources and the strain we put on the environment. And secondly, it seems to miss the larger point that degrowth is coming regardless of what we think about it.

Our current lifestyle cannot be supported without fossil fuels. You can’t have large cargo ships, industry that requires high heat and heavy machinery without oil, gas and coal. Even if somehow we ramped up to nuclear in time, electricity is simply unsuited as an energy source for many of the things that we currently rely upon. Good luck running a mine using lithium batteries, generating fertilizers without natural gas, or even running an industrial farm without oil/diesel. And then there’s all the ways in which climate change is going to disrupt business as usual. So much of our infrastructure is useless without fossil fuels, but nobody seems to be really thinking about it outside a few marginal thinkers/think tanks (shout out to the Post Carbon Institute).

So it seems to me that there are really two things you can do. Write trite articles critiquing degrowthers for silly reasons, or actually focus on what the hell we’re going to try and manage this mess. Because managed degrowth strikes me as a hell of lot more pleasant than collapse, but collapse is where we’re heading.

Is it just me, or are these not studies on ‘degrowth’ per se, but how people feel about it? I didn’t need a study to tell me they wouldn’t like the medicine. It’s interesting, how various eschatologies, and conspiracy theories have converged on this moment, the end of history. It’s as if the stories were all true in their own ways, and teach of a common, repetitive (?) cycle of human hubris: First you learn to talk, then you learn to write, then you become telepathic (as I transmit these thoughts to you), then you blow up. Each advance predicates a species/civilizational rise in entropy, that predictably exceeds the carrying capacity of the ecosystem. Has all this happened before? Is the purpose of surviving the inevitable horrors, to ensure it does happen again? Can I be Solomon this time?

I’ve noticed, and I’m sure I’m not the only one, that emergent, initially nonpartisan concepts such as degrowth quickly face a sort of reframing attack intended to either co-opt or demonize the concept. Police reform is another great example. As soon as one ideological wing sees a source for potential donors/voters/foot soldiers, the NGO/media complex descends like vultures to reframe the issue on the left-right axis, discourage any radical solutions, and preserve status quo positions. The other team then misrepresents the concept as unreasonable and reinforces the left-right framing to prevent any loss of support. (Is there a good term for this dynamic?)

Degrowth has a political wing, to be sure, and I’d guess that most would have traditionally seen themselves as Green or Green-adjacent progs, with a few traditionalists in the mix. But there’s a large contingent of people like JMG, CHS, eco-aware preppers, and “solarpunks” who simply see degrowth as an inevitability and don’t want to get blindsided. They may have various political theories about how we got here, but generally they don’t seem to see a viable solution other than preparing themselves and their local communities for the worst.

To me, the worst part of the political reframing of degrowth is that it shuts out these voices. We should absolutely be prepared for the worst, even if it never happens. We built the Internet to be able to withstand a nuclear attack that never came about, and this decentralization brought with it a number of positive side effects. It’s possible that building parallel, local, low impact infrastructure as a civilizational backup of sorts would have similar positive side-effects, even if fusion power and asteroid mining come online tomorrow and bring us all the infinite junk we could ever hope for.

Imagine if the Y2K bug crisis happened today. Whichever side claimed the crisis first as a partisan issue would face endless denial and stonewalling from the other team. I am not sure we’d be able to address it in time.

A response to this review by Jason Hickel.

And another.

While this is obviously a hostile take on degrowth, I’m glad that Yves, who is sympathetic to degrowth, nevertheless presents an alternative perspective.

To my mind “degrowth” is a term which automatically generates a wrong perspective on the problem. The problem, after all, is that we cannot sustain our civilisation at its present level of energy and material usage. Therefore, we must lower the level of energy and material usage. Retaining any currently-plausible techniques, this would entail reducing the living standards of the population, which is politically almost intolerable and also carries with it the virtual certainty that the ruling class would do this to the majority while preserving or even expanding their own living standards.

Of course, the danger in saying “we must change the way that we do things in order to avoid catastrophic human suffering” runs up against the kind of “we can save the world through buying electric cars” argument which is unfortunately the standard efflux of the captured “environmental” lobbies. In other words, the danger is that an honest problem – how do we save civilisation from destroying itself without generating a Gibson-style Jackpot for most of the populace? – becomes just another tool for the ruling class to enrich itself.

Which means that we need extremely careful and honest debate around degrowth, and I suspect that a lot of the material which this article critiques deserves the criticism it receives. I know that in South Africa the kind of people who talk about degrowth are not the kind of people I would buy a used rhino horn from.

You might find the work of the Post Carbon Institute, Kate Raworth and Ugo Bardi interesting.

Kate Raworth isn’t exactly degrowth (and has criticized the rather flabby definitions), but presents an economic model of how we should be thinking about the problem (how can we flourish given a set of environmental and resource constraints).

The Post Carbon Institute take seriously the problem that energy is not fungible, and that we will have less of it. There are things that you can do with oil/gas/coal – that are simply not possible with electricity. They’ve written reports on what this means for society generally (and how we need to think about adaption), as well as focusing on things like agriculture. They’re heavily influenced by systems thinking (a must if you’re going to think about these issues).

Ugo Bardi is an Italian chemist who became interested in these topics as part of the peak oil movement that revolved around the Oil Drum blog (which is a where a lot of interesting thinkers began their path), and who writes seriously about these topics. Another systems thinker.

Good point. I was going to ask how growth-based research would fare measured against the same kind of standards discussed here. You can argue that if the authors fail to direct the same criticisms at pro-growth work, they’re operating in bad faith. But even if that’s true (and I think it is) that doesn’t mean the criticisms are invalid.

As you mention (and Yves does as well) the fundamental problem is that climate science shows very clearly that degrowth is coming, whether we like it or not, probably some time in the next few decades and certainly in the next century. Historic examples for what that might look like (e.g. the fall of Rome) are not pretty, and there is an urgent need to come up with better options that involve less pain and better outcomes for humanity.

If existing studies on degrowth are deficient, then surely economic theories that deny even the possibility of degrowth and assume the status quo will continue forever, in defiance of everything climate science tells us, are even more so. Where is the acknowledgement of this? Absent that perspective, this just comes across as academic credentialism and turf protection.

One could argue, so much of what we do is predicated on toxicity to begin with, that losing swathes of the “economy” would instantly raise the standard of living, if you measure that in health and wellness, and not lofts and Lamborghinis.

we must first get rid of the god awful free trade agreements that have locked a good portion of the world, into fascist proto colonies.

restore sovereignty and democratic control, then take on finance, wall street, insurance and the oligarchs.

invest in ourselves, there will be a lot less fossil fuels burned then. besides all of the minerals and resources free trade is burning through at a rate that’s unsustainable.

cash crops will become less desirable. as well as capitalist free trade sweatshops.

Greater insights likely would arise from archeology. Degrowth has occurred time and time again as civilisations collapse. Though we can’t ask the average person how they felt about it.

We have recently experienced two real life experiences with economic degrowth.

The more distant occurrence was at the economic slowdown of the Global Financial Crises around 2011.

The second was during the covid-19 lockdown when much economic activity was suspended.

As I recall in both cases atmospheric CO2 was still added but at below trend.

So the world flirted with a form of degrowth in both cases but quickly reverted to growth pursuit.

Degrowth is not something that a US politician can promote and still survive in office. Far too many people are struggling economically and they do not want to do with a projected “less”.

I’d like to see a GDP that was split into two parts, one part is the “growth” that harmed the earth’s life support system and the second part that improved the earth.

As it is now, my view of GDP is that it is less a measure of progress and more a measure of falling further behind.

“I’d like to see a GDP that was split into two parts, one part is the “growth” that harmed the earth’s life support system and the second part that improved the earth.”

Index of Sustainable Economic Welfare, originally proposed by Herman Daly and John B. Cobb, Jr. in 1989. Updated 1994: For the Common Good: Redirecting the Economy Toward Community, the Environment and a Sustainable Future.

Available links from the relevant literature: Here, here, and here.

Those folks down there in southeast Louisiana are on the verge of a tremendous growth spurt. Yes, that´s right. As soon as Hurricane Francine departs on her way up the River, there will be a tremendous spurt of growth. Construction will boom! There will be overwhelming demand for home carpeting, appliances and autombiles; it will be a bonanza for the roofers. And just wait till they send the bill for putting all the oil rigs back together! The GNP for Louisiana will skyrocket as a result of all this spending. Growth!! And all those people who live down there will be better off, right? It is obvious that using the long disgraced metric of GDP as a means of measuring ¨growth¨ or ¨people being better offf than they were¨ is just more academic b*****t worked up by the Piled higher and Deeper crowd.

¨Growth¨ has little or nothing to do with either people or the environment being better off than they were before. The idea of growth by itself has no meaning: growth of what? The probem I see with much of modern economics that has an overdependence on mathematics. Trying to develop a formula or a graph to explain the concept of someone or something being better off relies on a dependent variable, and the one that is almost always used is a unit of money. Mathematic analysis can be useful some times, but those using it need to step back from time to time and see if it really reflects reality. In the case of using GDP to measure growth that step is long overdue. It is absolutely essential to identify who or what winds up better off and who or what is made worse off. As long as degrowth is seen as shrinking the GDP number, people are simply asking thw wrong question. More Piled higher and Deeper.

This tweet from 9/8/24 NC Links says it all:

The world is run by lunatics.

saved that one – amen –

Aren’t the IPCC scenarios in some ways studies in degrowth?

We have already surpassed the mild one with temperatures and the goalpost is being moved as we speak.

The story of the fabled frog boiling slowly always leaves the essential fact out, the frog had its brain removed…

With the demographic decline in many western/developed countries, some degrowth is baked in.

What these authors ignore is that ‘degrowth’ is inevitable as there is just no way the global society/economy, especially the West, can continue as it is. Fostering climate change is only one of the problems resulting from a vast, surveilled, precarious population. Human beings cannot last long plagued by consumerism and über capitalism’s movement to indebt everyone but a few lucky rentiers.

The age of limits has arrived- Climate, Resource Depletion, Economic/Societal collapse, Ocean Acidification… Degrowth is “baked in.”

This post looks in all the wrong places to assess u.s. progress toward degrowth. Economic studies and statistics are the very last places to look for measures of degrowth. A cursory review of the accuracy and reality of economic studies in evaluating basic ‘ground-truth’ in the economy should be sufficient to demonstrate the limited value [opining as kindly as possible] of economic studies. The solid scientific basis for this claim can be readily observed empirically.

Degrowth? Didn’t the u.s. do a lot of degrowth during the late 20th Century by shipping its jobs and production overseas? And much of the u.s. degrowth will kick-in shortly when the fracking wells start to play out. There are also significant efforts toward degrowth of consumption by everyone but our top 10%. Bipartisan efforts have been working to control consumption by increasing poverty and lowering living standards for all but the important people in our country. The GDP measure for growth deliberately hides the effectiveness of these measures toward degrowth. Of course resilience is quite a different matter. The lower levels of our top 10% need to worry, but the very ‘best’ of the u.s. Elite have off-shored much of their wealth and remain quite resilient. Admittedly, there are a few clouds. Resilience is of little importance to anyone except a few of the doomers. The u.s. is a proud Empire that prefers to meet its future at a dead-run face-first into the brick wall of the Imperial Collapse. [Just imagine the impacts of gasoline ‘issues’ on u.s. real estate. The suburbs just won’t be the same.]There is an overhang of gasoline and diesel consumption to support the long narrow supply chains feeding u.s. consumption. There are also some issues affecting the electric Grid that temporarily create more pollution than they will in a few short years as utility prices and fossil fuel prices climb to new heights and/or supplies of fossil fuels drop to new lows. All-in-all, I believe the u.s. is much farther along the road toward degrowth than current measures gauge and much much farther along once the short-term slack in immiseration meets tomorrow’s shortages.

The u.s. is far along the road toward degrowth, as the lower tiers of our top 10% are becoming gradually aware. As for pollution, the pollution residuals in the wasteful u.s. economy are winding down and while the very ‘best’ of the u.s. Elite can increase their pollution and waste to compensate for the declines in consumption the rest of us experience and will shortly experience to a much greater extent, there is only so much our Elites can do.

/sarc

Remember the Iron Rule of Economists:

1) For every economist there is an economist with the opposite view

2) They are both wrong