This is Naked Capitalism fundraising week. 141 donors have already invested in our efforts to combat corruption and predatory conduct, particularly in the financial realm. Please join us and participate via our donation page, which shows how to give via check, credit card, debit card, PayPal. Clover, or Wise. Read about why we’re doing this fundraiser, what we’ve accomplished in the last year,, and our current goal, strengthening our IT infrastructure.

Yves here. The post below has an extremely important finding: that the damage done by deindustrialization is lasting, extending across generations and even afflicting those able to relocate. This shows that the societal cost of outsourcing and offshoring to health and earning potential. This finding is particularly jarring, since as yours truly has described over many years, at many companies, the financial case for offshoring was often weak and rarely allowed for costs like loss of know-how and increased business risk. A couple of public company executives have told me that even in the face of not-compelling forecasts, they still went ahead with offshoring plans because they knew the announcement would give the stock a pop.

And remember, this study looked at the coal mining industry, with its famously backbreaking and often health-harming labor. But in the UK, these were union jobs, or at least had been union jobs. I was in London on an extended assignment when the Thatcher government was prosecuting its ultimately successful campaign to break the coal miners’ union. It was front page news most days.

The authors find the shock of a pit closure had a huge, negative lifetime impact on children. Yet our putative betters have handwave answers of the “Let them eat training” sort.

By Björn Brey, Assistant Professor Norwegian School of Economics (NHH) and Valeria Rueda, Associate Professor of Economics University Of Nottingham. Originally published at VoxEU

Industrial decline has been directly linked to a worsening of various social and economic indicators. This column examines how the impacts of deindustrialisation in the UK reverberate across generations, finding significant effects on the health, wealth, and living standards of those who grew up under industrial decline. The ability to migrate to wealthier parts of the country is not sufficient to offset these negative effects.

The recent decline in industrial jobs in developed and emerging countries has been linked to worsened health (Case and Deaton 2020, Case 2020), the disintegration of family ties (Autor et al. 2018), and the formation of a geography of political discontent (Autor et al. 2020, Rodríguez-Pose 2018, Rodríguez-Pose et al. 2024). Previously prosperous places are now ‘left behind’, with worse relative living standards, education, and productivity (Moretti 2022, Overman and Xu 2022). Few countries in the developed world have seen such stark increases in regional inequality as the UK, the country with the fastest deindustrialisation in the developed world (Mcann 2019, Stansbury et al. 2023).

In this column, we show that deindustrialisation has persistently affected living standards in the UK. Our recent research documents effects on the health, wealth, and living standards of those who grow up under industrial decline. These effects persist even if people migrate out of affected regions, and they carry over generations (Brey and Rueda 2024). Industrial decline thus not only affects those who work in endangered industries; their children and their grandchildren are also durably worse off. Moreover, the availability of better economic conditions elsewhere does not fully mitigate this impact. Deindustrialisation thus directly threatens equality of opportunities for future generations.

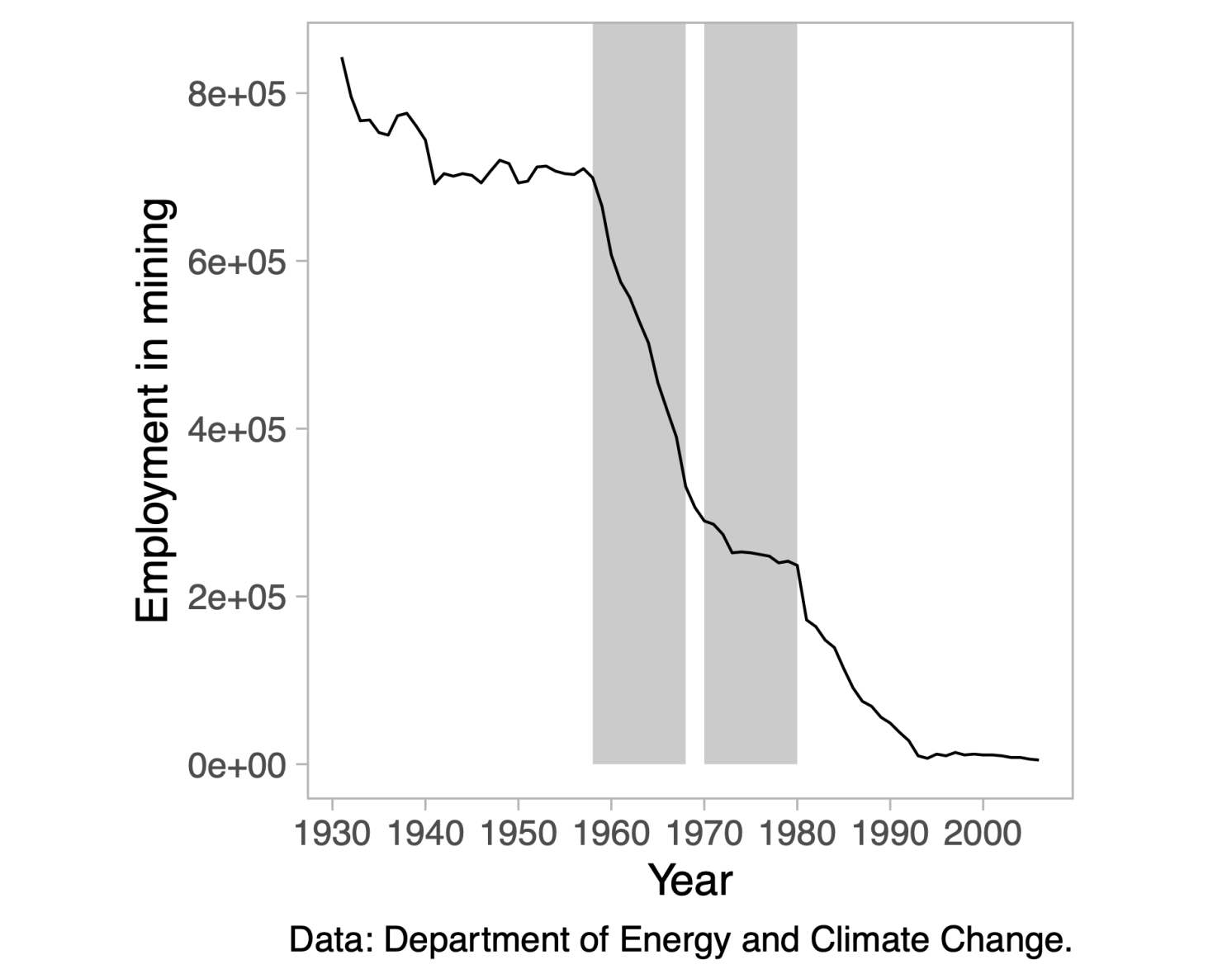

We focus on the collapse of the British coal industry, one of the starkest cases of industrial decline in the 20th century. Economic historians have extensively written about the importance of Britain’s coal in the Industrial Revolution (e.g. Pomeranz 2000, Allen 2009, Wrigley 2010, Fernihough and O’Rourke 2021). Coal mining employed more than 700,000 people by the end of the 1950s. That number halved within a decade, following the industry’s most dramatic shrinkage post WW2 (see Figure 1). Waves of pit closures continued washing over British coal production until its virtual disappearance in the 1990s. Today, the former coalfields consistently rank among areas with the highest levels of deprivation in the country, a matter of sufficient public concern to grant the formation of an all-party parliamentary research group working on policy proposals for these regions (All-Party Parliamentary Group on Coalfield Communities 2023).

Figure 1 Employment in mining in the UK in the twentieth century

Note: See Brey and Rueda (2024) for details.

Our paper estimates the impact of mine closures on those who experienced this economic shock as children. We leverage longitudinal data that follows all children born during a week of 1958 and of 1970 (UK Longitudinal Studies). These data allow us to track people throughout their life and gather information on their parents and their children. We combine them with data produced and shared by the Northern Mine Research Society giving information on all coal mines that have operated in the UK. We can thus compare outcomes, at each life stage, between counties and cohorts, depending on their exposure to mine closures and conditional on a rich set of controls. We ensure that our findings are not driven by unobserved confounders of pit closures and living standards in a variety of ways. In particular, we verify that before the shock, children are comparable: at birth, there is no relation between health outcomes and socioeconomic conditions depending on later exposure to the shock. Moreover, using fixed effects, we account for determinants of living standards that are specific to each county and to each cohort. Finally, we use an instrumental variable that exploits the fact that older pits were closed first.

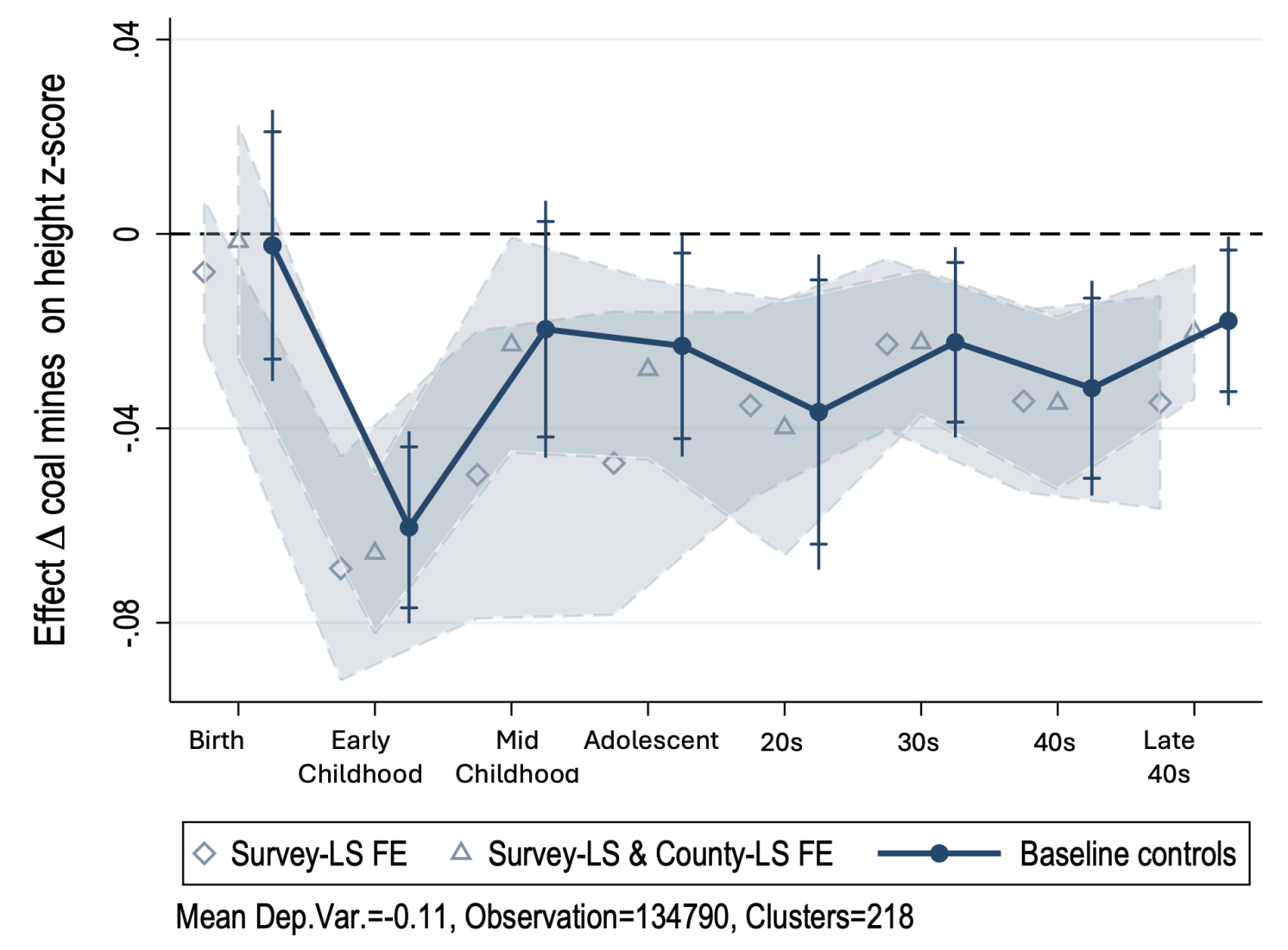

Finding 1: Individuals Exposed to Pit Closures During Childhood Have Worse Health Throughout Life

Individuals who grow up in counties with a higher ratio of pit closures to population are significantly shorter. Height, a well-established indicator of overall health and living conditions, correlates with economic outcomes in adulthood (e.g. Hatton 2014). Height gaps are strongest in early childhood; despite some catching-up, a significant difference persists into adulthood (see Figure 2). This adult gap – 4% of a z-score, or 0.3 cm – is substantial, comparable to the lower-bound estimated impact of the Irish famine on survivors’ height (Blum et al. 2022).

Figure 2 Effect of pit closures relative to the population on height over life

Note: Coefficients are standardised.

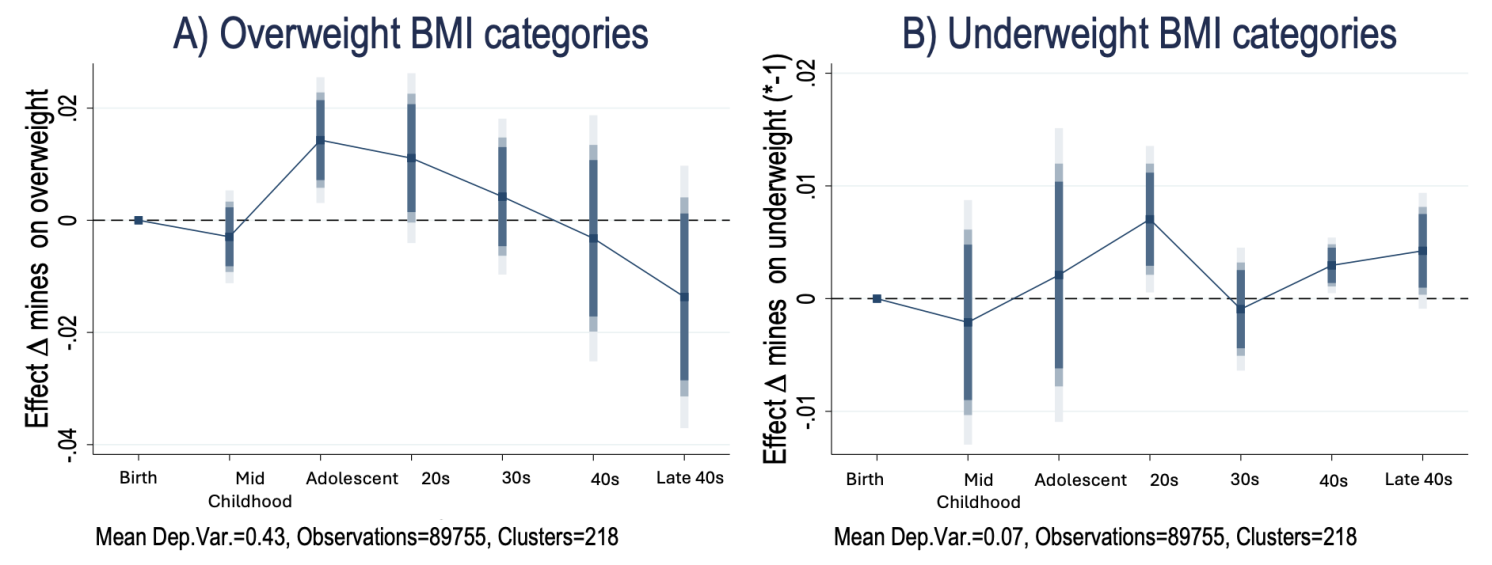

Furthermore, those exposed to pit closures in childhood have BMIs that lean more towards extreme categories, with the effect on overweight categories starting in adolescence to mid-30s and the one on underweight categories starting later in life (see Figure 3). Further analysis reveals that the impact on underweight is stronger for women, while that of overweight is slightly more pronounced for men.

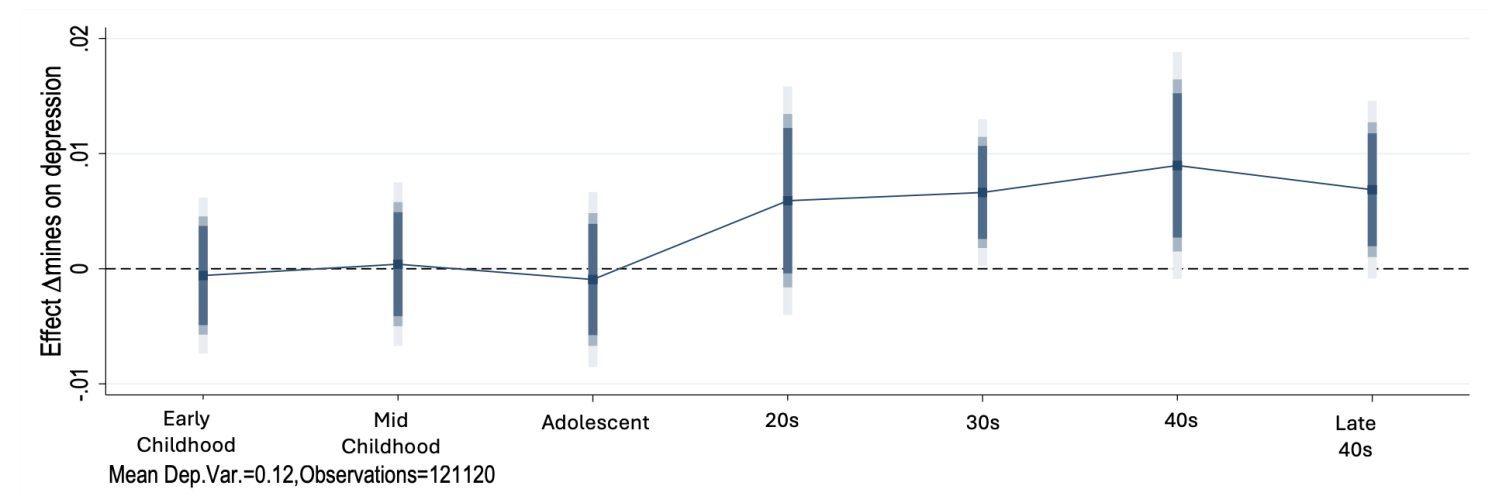

Finally, we also observe worse indicators of general physical health in childhood and higher incidences of a variety of health conditions in adulthood such as diabetes, back pain, and cancer. We also observe worse self-reported mental health in adulthood, including a markedly higher likelihood of states of depression (see Figure 4).

Figure 3 Effect of exposure to pit closure relative to the population on extreme BMI categories over life

Note: Coefficients are standardised.

Figure 4 Effect of exposure to pit closure relative to the population on reporting states of depression over life

Note: Coefficients are standardised.

Finding 2: Pit Closures Are Associated with Worse Living Conditions in Childhood

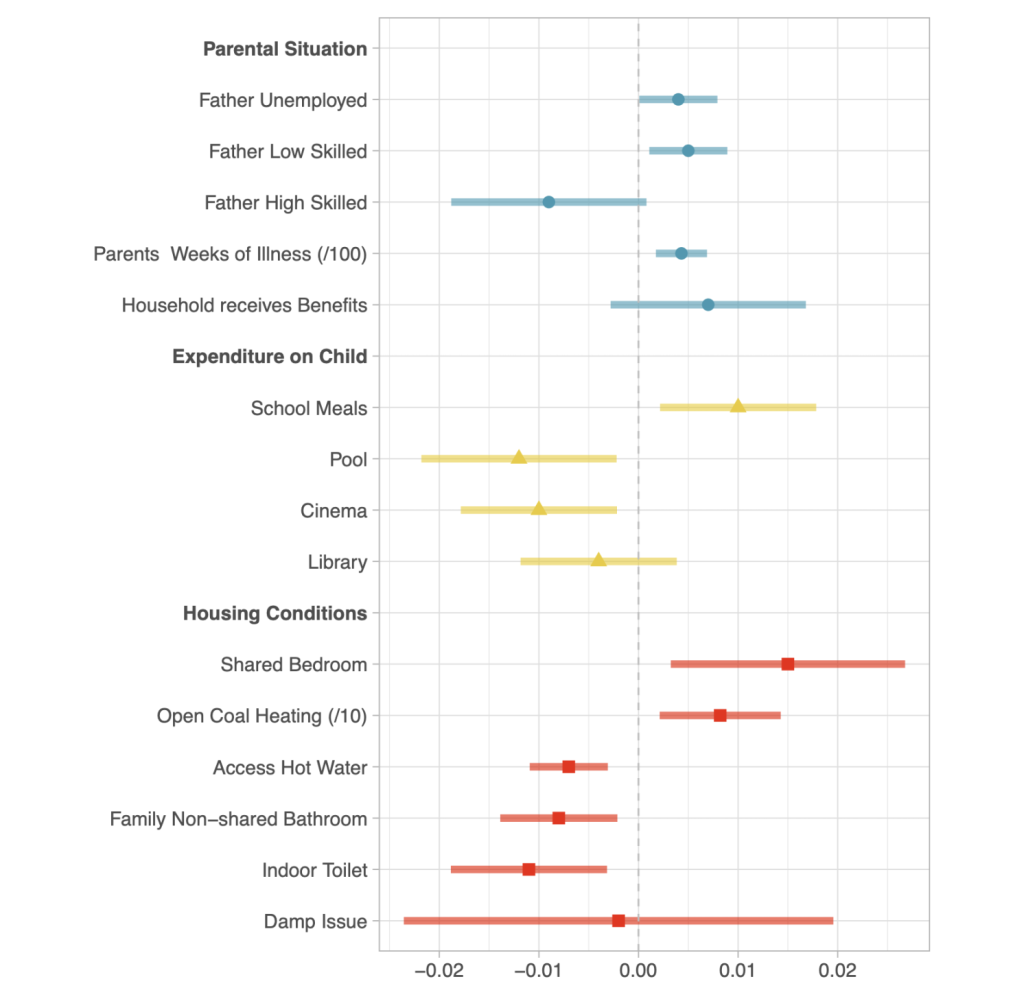

What can explain the durable impact of pit closure on health? Figure 5 illustrates that mine closures correlate with more deprived living conditions in in mid-childhood (age 10): parents are more likely to have worse employment outcomes, to have taken weeks off work due to illness and to receive benefits; children receive fewer resources from the family, as proxied by leisure expenses and a higher propensity to receive free school meals; finally, their housing conditions are worse following a variety of indicators. In sum, affected children experience economic hardship in childhood, potentially explaining worse health outcomes over life.

Figure 5 Effect of exposure to pit closure relative to the population on living environment of children

Finding 3: Individuals Exposed to Pit closures During Childhood Accumulate Less Wealth as Adults and Their Children Are Less Healthy

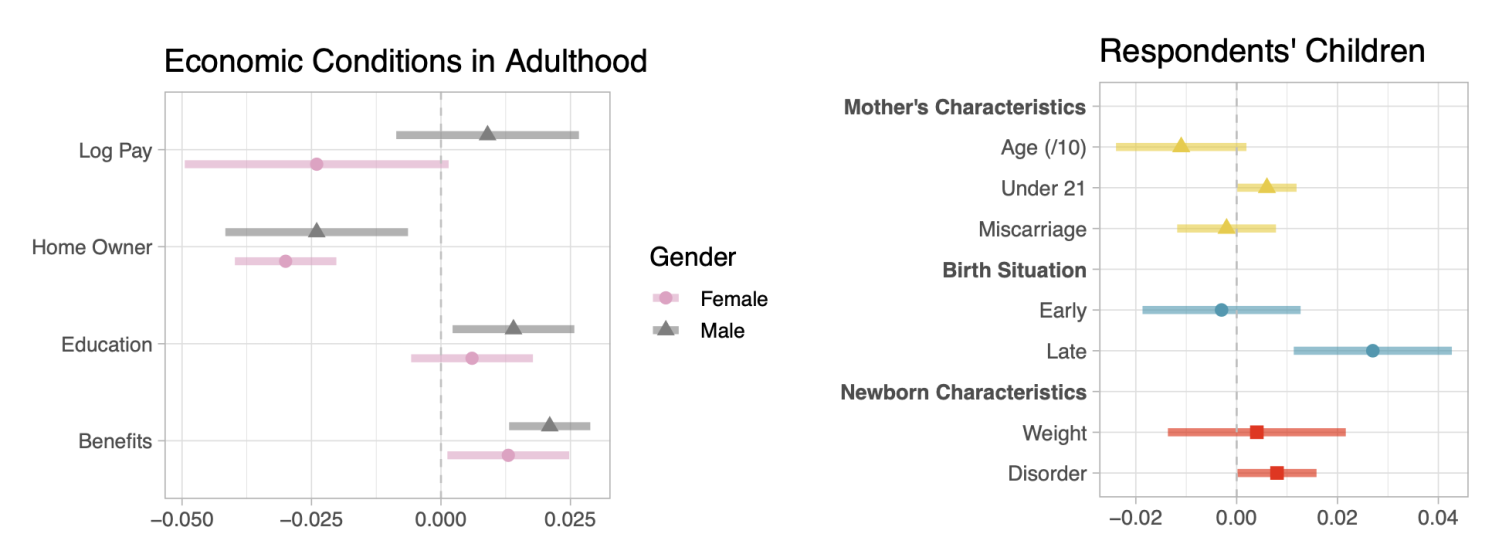

How persistent is this effect? Does it affect economic conditions in adulthood? Does it carry through to the next generation? Figure 6 shows that the economic impact carries through adulthood, with respondents less likely to be homeowners and more likely to receive benefits, women also tend to earn less (left-hand panel). Moreover, when they have children, their sons and daughters have a more difficult start in life: the parents have them much earlier (teenage years), and the babies are more likely to be born late and to have had some health condition at birth (right-hand side panel, outcome “Disorder”).

Interestingly, exposure to pit closures in childhood is associated with better education, significantly so for men. This result aligns with previous findings showing that manufacturing and mining industries increase the opportunity cost of education, especially for men (Black et al. 2005, Esposito and Abramson 2021, Franck and Galor 2021). Further research is needed to understand why despite higher male education, exposure to the shock still shapes wealth. Potential explanatory channels are the direct impact of health, inheritance, and assortative matching on the marriage market.

Figure 6 Effect of exposure to pit closure relative to the population of economic conditions in adulthood and children of respondents

Finding 4: Migration is an Imperfect Mitigation Strategy

In the aftermath of local economic shocks, migrating to opportunity is a natural coping strategy. In our case, this was the option favoured by the government and the reason invoked to dismiss any additional targeted support. Longitudinal studies permit tracking movers. We observe three main facts about migration (see Section 5.4 in Brey and Rueda 2024). First, pit closures did not trigger mobility later in life. If anything, the probability of migrating decreases. Although incentives to out-migrate were heightened, the resources to do so decreased, an effect appears to dominate. Second, migration was not accessible to all. Those who migrated were born in families with more educated mothers and fathers or with fewer local ties (younger parents of single-parent households). Finally, the impact of the shock is diminished but not fully reverted after migration. Taken together, our findings suggest that migration was not a perfect solution. Access to it was unequally distributed and those who migrated still see some negative impact.

Lessons

Our research shows that deindustrialisation can durably affect living standards, and the effects are carried across multiple generations. These findings are salient to current policy debates about increasing levels of inequality and poverty in developed countries (e.g. Institute for Fiscal Studies 2024). They highlight that in the absence of any additional support, people born in places that industries have left behind carry health and economic scars that are transmitted to the next generation. These long-lasting consequences are not resolved by access to better opportunities. Few people move, and those who do keep a scar.

See the original post for references

I think this research conflates two quite distinct settlement types – mining communities and industrial communities, both of which have been badly hit by deindustrialisation but usually have quite distinct trajectories when the original industries become outdated or defunct (or in the case of the British coal industry, murdered).

Mining is a highly specialised activity with skills and plant which can’t be easily transferred to other activities. Definitionally, it tends to focus on where the mineral reserves are, and these are often not conveniently located as far as any other type of activity is concerned. Most Welsh mining communities, for example, are in mountain areas with no real alternatives for other industry. Settlements have grown up around mineral resources since the age of flint, and they usually died out forever once the mineral reserves are exhausted – the world is full of mining ghost towns for a reason. Younger men with skills moved to new reserves (for example, numerous Cornish copper miners moved to the US in the 19th Century), leaving behind the less mobile.

Rust belt industrial areas were usually located close to coal mines, as to make, for example, steel you need more coal than iron ore, so it always made sense to shift the ore to the coal, not vice versa. The exception would be where there is a very convenient water link that allows you to bring the coal to the ore, but the US is one of the few parts of the world where geography was so obliging. So early industrial cities, from probably the first, Birmingham in the UK, to Manchester, Dusseldorf, etc., etc., were located at convenient nodes where the coal and iron (and other essential minerals) could be brought together, first by water, later by train.

The latter process means that many industrial cities still have a certain locational logic, even after the coal and iron runs out. They are left with a legacy of infrastructure, and perhaps most importantly, a variety of human skills which can, with luck and some effort, be transferred. You can often see this process layered almost like archaeology. In parts of the West Midlands in the UK, dig into any old industrial site (preferably with full hazmat), at the base you’ll find old coal works with the remains of early glass making and specialist iron work. This was displaced in the mid-19th Century by mostly chemical manufacturers (either associated with steel working or the phosphorous industry). The upper layer, from the 20th Century onwards, will be marked by the residues of more advanced forging and steel work. All these were based on the original coal layers (there are multiple coal beds of varying quality beneath the entire region), but even when the coal ran out in the mid-20th century, the accumulated infrastructure (human and physical) kept the area going. Up until the 1980’s and the Tories decided to kill it all off. But even then, the area has still, if not quite prospered, maintained a reasonable economy, mostly based on services. So while rust belt cities can shrink and decay, they rarely die completely, and often can prosper (Manchester and Leipzig or Bilbao being examples in Europe). The cities that have failed most severely tend to be those which were highly focused on a narrow industry or service – for example, Liverpool (mostly a trading port) has never really recovered from its loss of importance as an entrepot, while Manchester has relatively speaking done much better. Its probably simply a matter of scale – Manchester was always bigger, and so got the first bite of any new industry coming to the region.

So I think its a category error to conflate the death of mining communities with de-industralized urban areas. The latter can prosper if there is sufficient focus on building on existing strengths (locational, infrastructural, and a skills base). Scale also seems extremely important. Big cities have a momentum that ensures that they just keep attracting people and resources, long after apparent locational/economic logic should see them stagnate. Smaller cities can struggle, even with intensive direct investment. Sometimes cities can recover through direct government intervention – sometimes it just seems to happen anyway.

Thanks. Nottingham is an unfortunate victim of both phenomena you mention. It suffered the perfect storm of political decisions in the post-war era. The Great Central Railway was a victim of the Beeching cuts, yet was probably the most insane of a great number of truly insane cuts made to British Rail: Yes, the line duplicated a lot of the (retained) Midland Mainline but its “flaw” (that it didn’t serve some key cities between London and Nottingham) was also its benefit. Its incredibly straight nature meant that it would have been perfect for HS2 and north of Nottingham it served all the South Notts mining communities, which after its 1960s closure put them in a very precarious position in terms of getting their coal to where it was needed.

The Lace Market suffered deindustrialisation. Meanwhile Thatcher’s “divide and rule” policy (getting parts of the South Notts miners onside to weaken Scargill’s official NUM) did Nottm no favours as when she won, she simply closed their mines anyway. I had reason to look up the public data on prescriptions for Pregabalin a few years ago by practice across Nottm and outlying suburbs: Hucknall practice (the one with the highest proportion of ex-miners) was a massive outlier. and the patients were NOT just the ex-miners with chronic pain but (judging by age bands) their offspring.

When I was a kid in late 70s and 80s we lived in one of the last privately built/owned estates in north Nottm. The police go in convoys to not just that estate these days but also frequently around the “posher” estate my parents moved to in mid 1990s and where we are now. We are part of the northern half of the “doughnut” of parliamentary constituencies surrounding metropolitan Nottingham – key section of the “red wall”. Yet nobody around here has enthusiasm for Labour, who they feel bitterly let them down down during the pit closure and deindustrialisation period of the 1980s. The neighbouring constituency is Ashfield (of Lee 30p Anderson fame) – Ashfield is demonstrably a failed suburb; all the former pit villages in it and north of where I live are awful; social order has gone almost entirely.

There was some regeneration in the New Labour era (those bits of the main railway line not sold off were repurposed as tramlines and other schemes built badly needed NHS buildings) but it was all funny money aka PFI. There is a farm shop 2 miles from here: nice but still nothing compared to the ones that were almost every 300 metres along the coast of Norfolk (a stone’s throw from Sandringham) where we holidayed last week. It’s those contrasts that caused me to point out to dad just how much of a failed state we are. Plus you sense a simmering resentment under the surface, which is why people in Ashfield have given up on all the major parties. The obituaries in local papers are full of deaths of people of age/fitness that we never used to see. Dark times.

Ah, the Great Central Rail Line – closing this was probably the most bafflingly stupid decisions in economic history. It was one of the last major railways built in the UK (at least until the Channel Tunnel Rail link) – amazing to think there was a nearly a century between them. It was also built arrow straight, which is a godsend to railway operators. Once the project managers took over from the engineers aroundabout 1850 in UK rail engineering, most lines were much more poorly designed and constructed (albeit, far more sensible in accounting terms). The early railway lines like London to Bristol or Dublin to Belfast – flat and direct – have proven far cheaper to maintain and keep running than the later ones that made the rolling stock do the hard work of going up and down grades and making turns. The Great Central Line was an exception. So its loss as a line and route has in reality cost the UK economy many billions over the decades. The record of HSR shows it would probably take the best part of 100 billion to build something similar from scratch.

I don’t know Nottingham very well, but it seems to me to have suffered relative to cities like Birmingham and Manchester in just not being big enough to be truly self sustaining, while lacking the direct link to London that could allow it to benefit from some overspill. It is interesting to see the different directions East Midlands cities like Nottingham, Sheffield, Derby and Leicester have taken, although the only real conclusion seems to be that there aren’t any hard and fast rules when it comes to urban success or failure.

Glad you’re aware of it. I’ve just had a YT notification of the re-opening (as, alas, only a heritage line, like the other bits) of the latest section of it leading north into Nottingham here.

Maybe I’m a bit tin foily but I have a sneaking suspicion that these people resuscitating sections of the line as heritage railways have an ulterior motive – preparing the ground for relaunching the line as a proper part of BR as a “much cheaper, better HS2”. I find it frankly odd that they don’t allow comments on their YT vids and their videos of “very quiet, under-the-radar buyouts” of land to connect the land they already own would be exactly what I’d do if I wanted to avoid drawing attention to what I was doing and having land bankers put prices up.

Sections that were sold and had new builds put on them are frankly economically useless (hosting now defunct factories) and Marylebone has always been known to have spare capacity (plus the “new” St Pancras could I’m sure deal with a new line….particularly if you *ahem* encouraged those people at Google next door doing all that “wonderful” AI stuff to go away).

The straw that broke Nottingham’s back was the move to unitary authorities by the Tories. Money from the posh rich backers of former MPs like Ken Clarke once upon a time cross-subsidised the rest of the shire and Nottm city. Now the city (which is extraordinarily small in terms of geography and includes virtually nobody rich) gets no money from the county and so has been one of the first to go to the wall. Meanwhile some relatively posh southern AT SEA LEVEL AND ON A RIVER suburbs outside the city boundary enjoy comparatively low Council Tax. They may change their tune within 50 years: the “second, never wanted in the first place, shopping centre – BroadMarsh ” is currently an eyesore that looks like those post-apocalyptic pictures of whole blocks of Detroit, since its owner, INTU, went backrupt midway through redeveloping it. Given newest projections on sea level rise I reckon it should go back to what it was named after – “the Broad Marsh” since that’s what it’s gonna be soon. Let South Nottm revert to what it was. Schaudenfraude? Yeah.

PK and Terry

This was a fascinating and informative exchange.

Thank you!

Seconded. Thank you both.

The GCR was also the only British railway line built to Continental kinematic loading gauge (UEC something or other) because of its Edwardian vision of building a Channel tunnel. If it were in service today, it would be a fantastic freight artery.

There was a scheme for reopening it for rail freight over ten years ago. The promoters seem to have vanished. Taking freight off the other passenger lines would have delivered some of the benefits of HS2 but much more cheaply so the cynic in me thinks it was knifed by vested interests.

On a roundabout link from deindustrialisation, what do you think of Kneecap, PK? They’re my latest enthusiasm, having seen the film which rocks.

Tying it back to de-industrialisation, Belfast was a great shipbuilding (the Titanic!) and textile town (linen) and an early aviation / military industrial complex node (Shorts brothers aviation). But these industries died and partition left both Unionist and Republican working class on their uppers economically. However, for a long time, NI in the Troubles had one of the lowest suicide rates in the world. Now that the Troubles are over, its troubles of neoliberalism have begun and it has an epidemic of deaths of despair – which ironically it didn’t when there was a social cause to live and die for.

I remember that freight proposal – I’m not sure what happened to it. But as a general rule, railway projects almost never come to pass without direct government support from the beginning, there are just too many financial and legal obstacles (this applied just as much in the 19th century as today). Plus of course road freight is receives a massive hidden subsidy in the form of free road use. Otherwise, it would never compete with rail.

I’ve always been curious as to how Belfast became so prominent in engineering, given that it so far from the heartlands of the industrial revolution (not to mention northern Ireland lacked good quality coal and steel). I think something can be said for the peculiar genius of the Anglo-Irish aristocracy. They never numbered more than a few hundred thousand, but they included a disproportionate number of military, scientific, industrial and literature geniuses. The Parsons family alone – with their base in the middle of the bogs of Offaly, contributed much to the industrial revolution, not least through the invention of the steam turbine (and this was just the day job – successive Earls of Rosse pretty much dominated astronomy for the 19th Century).

Up the Anglo-Irish! Their day will come…. :-)

Perhaps they’re due a critical reappraisal. If it weren’t for key Irish home rule protestants, a lot of early work in preserving and reviving Irish wouldn’t have been done.

I imagine Belfast owes something to (1) the fantastic anchorages of the Ulster loughs and (2) the linkages with Glasgow, which was the heavy industry powerhouse of the Empire, in a way that is not properly appreciated.

Northern England span and wove textiles and processed chemicals but only Sheffield forged much. Whereas Glasgow was all plating and riveting and forging and casting, as well as textiles and chemical industry (chlorine bleaching invented in St Rollox by Tennant’s, still going strong). If you wanted a ship or a crane or a train or a steel mill building etc in the late 19th century, the chances are it was made on the Clyde.

A lot of Ulster Scots would have considered Belfast a natural location for an industrial business, given it already had an urban manufacturing population through the linen industry and an educated one to boot: like my comment about the Welsh, the Scots and the Irish valued scholarship and had grammar schools and Universities well in excess of the English on a per capita basis.

I know these areas and I find your comments really superb. It is excellent to hear on the ground detail rather than seagull viewpoints.

I have to differ with you based on the US. The de-industrialized areas are mill towns, usually not large (5,000 to 30,000 people). They do fall apart when their big employer, the town’s raison d’etre, shutters.

You insinuate those workers do not have specialized skills which is not the case. And those skills are not valued in other industries or fields.. American employers have been setting very narrow specifications for new hires for decades and are not willing to do more than engage in very minimal training.

A similar fate befell small European towns whose economic life relied upon a single local firm: collapse after the dominant employer closed during one of the successive crises of the last 50 years.

I guess something we forget is that the examples PlutoniumKun mentions — Birmingham Manchester, Düsseldorf — have a long history and were already successful, important cities back in the Middle Ages for reasons that had nothing to do with modern steelmaking. Thus, they have some intrinsic advantages that make them suitable centres of economic activity anyway, and being larger, they are more diversified than the smaller towns dependent on a single paper mill, spinning mill, cannery, shipyard, or whatever. Most cities and towns in the USA are historically very recent, and I presume that, for many, the reason for their existence disappeared with their dominant firm.

Lavenham in Suffolk was a village my friends showed me a decade ago which I never would have believed was in the top 20 cities of England in medieval times – all on the basis of the wool trade (and more specifically an ability to do “blue” stuff and dyeing things blue was historically very expensive). Thus, as you said, not being diversified was a death-knell in long-term.

Nottingham was regarded very highly mid millennium but it suffered from political shenanigans: The English Civil War may have kicked off here but friction was already causing problems due to the fact the “city” limits were so extraordinarily limited and the land immediately outside these was owned by distant members of the aristocracy who forbade growth and a more diversified economy that the city rapidly fell down the ladder of prosperity during the industrial revolution – I had no idea how many riots kicked off in this city til a YT video recently! We only learn (at best) the 20th century riots when the Windrush people were settled here, without any attempt to expand the city to address their needs.

Thus I think, albeit for different reasons, Nottingham looks more like one of the USA towns you mention. Which is ironic, since if you count its suburbs/exurbs, it is also much more like a USA city than many British cities (with an “effective” population that is perhaps 5x as large as its quoted population based on city limits).

I think the UK cities you name may also have had advantages that they were not “already carved up” by major aristocrats, allowing growth and stopping over-specialisation. The vids I have watched over how the 18th-20th century governance of Nottingham are eye-openers: the previous “walled garden” of mid millennium Nottingham that made it so popular encouraged local politicians to stop expansion and achieve any of the benefits of the industrial revolution. Lace. That’s it. Oh we found coal but that’s 5 miles north and we are definitely not expanding the city to draw upon that. Nottingham had some of the WORST life expectancy/health indicators of anywhere in the UK during the mid-industrial revolution and there were major riots every year, to no avail. IIRC the city council even lost Nottingham’s assumed role as the “heart of East Midlands trains” to Derby because it thought trains were a fad. Thus Nottingham to this day is really just a branch line (which would NOT have remained had the Great Central been kept). The East Coast mainline and Cross-Country Mainline have Derby as major terminus, despite fact Derby is increasingly a suburb of Nottingham. Even the wiki page, when quoting population statistics, includes one that takes the “Nottingham/Derby conurbation” as its broadest definition!

Yes, a few places get ‘frozen’ in size after their raison d’etre has passed. Kilmallock in Ireland is a tiny village, but in medieval times was a very important place. There are numerous examples across Europe. Larger examples of course would be Venice and Bruges. What I always find interesting is that they rarely disappear entirely. Urban areas usually only disappear when the entire civilization collapses, such as at Angkor Wat or the Mayan cities.

Its quite remarkable sometimes how stable the relative size of urban areas can be. If you look at a list of the biggest cities in Europe 1000 years ago, its not hugely different from today. The only really radical change was the big 19th century coal and steel cities, so you might say that their decline is just reverting to the mean. Much the same applies around the world – the big Silk Road cities of China are still generally the big cities of the region. The Middle East of course has had remarkable longevity in many of its most important urban areas. Only oil money has changed the ranking.

Defining border areas for cities is notoriously hard. Birmingham and Manchester are really just agglomerations of industrial villages and towns that gained their own identities in the 19th century, often due to the necessity to build water infrastructure. I often think of the example of Kokura, a once very important city in southern Japan, and chosen as one of the five cities to be nuked by the USAF. It survived through sheer luck, but then had the indignity of being written into extinction by the stroke of a bureaucrats pen in Tokyo, who decided it was no longer worthy of being a city and so became an outer suburb of Fukuoka. Thems the breaks.

I’m sure its very different in the US, especially with smaller specialised (i.e. single business) towns. But even then, mill towns in my experience can rot and decline, but nowhere near to the extent that a mining town can. Butte in Montana has in a century gone from being one of the most important cities in the US to being little more than a ghost town with a few tourist attractions.

I don’t have the figures to hand, but from memory the general mobility of people within the US is much higher than most other large countries, which is both an economic benefit and a curse – it can mean that people with productive skills are more likely to just pack up and go to where the jobs are, rather than try to build something up where they live. US policy implicitly supports this, in contrast to China, which actively tries to restrict internal movements to high growth areas, mostly for social reasons, but for economic ones too.

Yes. I grew up in the 1960s and 1970s in small southern city in Georgia with five large industrial employers, all union shops. Because Georgia is a Right-to-Work-for-Less state, each plant had freeloaders who refused to pay their union dues. In my experience these jerks were also those who used and misused the grievance procedure most often to get paid for (mostly) imaginary transgressions by management, but I digress. Anyway, only one of these plants is left 50 years later, the paper mill that now produces industrial cellulosic products. It shows. What was once a vibrant political economy is now dependent on antique (junk) shops and tourism and chi chi restaurants and cocktail bars. There are signs of recovery, but a rum distillery and a craft brewery that employ less than a hundred workers between them cannot make up for the loss of 3000 to 4000 union jobs in a city of 22,000 people (~55,000 in the county at the time). Local business owners were not particularly pro-union but they were aware that if they didn’t treat their employees well, a better-paying union job could be available close by if one was prepared to get his or her hands dirty (many were not and remained content in their white collars).

As far as skills go, the men, and very few women at the time, were highly skilled and most of them learned on the job, in both maintenance and production, with the one academic credential required: a high school diploma or a GED certificate.

I now live in a larger city that has been mangled by de-industrialization. Previously a railroad maintenance shop had the capacity to repair 100 locomotives at one time. And the (stolen from New England) cotton mills were humming. A big business now is tearing down abandoned houses. Plus the same craft breweries, restaurants, and bars, plus the occasional tire manufacturer or similar lured to the area with unnecessary tax breaks. More freeloading at a different level.

Back-breaking coal mining was nearly a thing of the past when Thatcher axed the coal unions. Even underground, excavation machines, augers, drills, electric rail cars and engines replaced men (and children).

Look to Canada’s East Kootenays where strip-mining coal, with Cat 250,000 pound D11dozers and 400 ton Haul trucks, move onto the rail for the haul to the port in Vancouver. In 2023 50 million tons of sea-borne coal left Canada where burning coal is verboten, but burning Canadian Coal without any environmental conditions outside of Canada is OK.

I am of South Wales, at one time the largest producing, and exporting, region in the world. I will not comment on any of the ‘Findings’ that the author identifies, but I would like to deliver a few of my own. Having spent the best part of seven hours touring around the ‘Valleys’ of Wales on my motorcycle yesterday, I can report as follows –

1. There are many more Public Houses (drinking establishments) shuttered than open for business.

2. Those that are open have the most welcoming attitude to strangers in their midst that I have encountered anywhere.

3. The ex-miner’s terraced houses are all occupied, as far as I can judge.

4. I have no idea how they all earn a living, other than ‘Welfare’, as there are just so very few businesses around.

5. I get the impression when talking with the locals that the ‘glue’ that holds them together is a shared resignation of hopelessness. Those that have had hope have left, and the rest survive in quiet desperation.

It’s so sad!

Not even many Welsh people appreciate just how prosperous south Wales was in the first period of the Industrial Revolution. It was very much at the cutting edge. But it was already in decline by the later part of the 19th Century for a number of reasons – one I think was the lack of a really good natural seaport with access to the valleys, plus the rapid exhaustion of the better coal seams, just as cheaper alternatives were made available.

By some measures, parts of South Wales are among the most deprived areas of Europe, although much depends on how you define the catchments – the southern coastal fringe is quite prosperous. Its noticeable from the last election that those areas are still very Labour – while Welsh nationalism is gathering some strength in northern and western Wales, coinciding I think with the language strongholds. There is also an older retired population, often English, which is deeply conservative.

I don’t know if there are any firm figures on this, but my perception is that the people there are deeply rooted – even in poverty they are reluctant to move even to England, much less farther afield. I suspect that it could be related to the Methodist mindset – looking ahead to salvation rather than dealing with life as it is. There used to be a long tradition of Welsh methodists coming to Ireland to convert the catholic heathens to the way of truth and light (one was an ancestor of mine). Most, like my 5-greats grandfather, lost his faith on encountering whiskey and catholic girls (family legends differ on which was most effective).

The South Wales coal fields initially exported through Newport but that silted up.

Then Cardiff Bay boomed as a port exporting coal (and iron ore could be brought in by sea so steel sprang up along the Welsh coast in Newport and Cardiff and Swansea). Roald Dahl’s Norwegian parents moved to Cardiff as part of a shipping business, which is why he was born in Llandaff near Cardiff cathedral.

Then finally the great purpose-built port at Barry was opened, just in time for the collapse.

I’m not sure that lack of train or port capacity was an issue for the Welsh coalfields, every valley had a line running south-ish into Cardiff Bay and there was direct line west to Barry across the top of the valleys. I don’t know about the mines being mined out, either.

I suspect the issue was cost structure: Britain fought WW1 and WW2 on her accumulated industrial capital of the 19th century, the railways in particular were ridden hard and put away wet after both world wars with no real investment and the British coal industry was so forward thinking that it establish the Forestry Commission in c. 1910 to ensure the future supply of wooden pit props rather than switch to steel! I suspect the cost of deep-mined Welsh coal, mined deep underground from small seams with minimal mechanisation and high pumping and maintenance costs could not compete with open-pit mining in British dominions like Canada and Australia.

I don’t think Methodism stops people emigrating. The Cornish who moved to Canada and the Welsh who founded Welsh-speaking towns in Argentina moved and they were all great Methodists. My guess is that what stops emigration is that these are fundamentally rural areas, where people mined and farmed in the same household or even in the same day. People were attached to their land. They were also attached to the collective capital they had built up, as the aristrocrats of labour, in their valley towns, of libraries and schools and hospitals and so on. The Welsh are great scholars, with a grammar school in every tiny village (my room-mate at College was from a grammar school in Botwnnog on the Lleyn peninsula, which is fly-speck of a village miles outside a much larger town of Pwhelli).

The ones who moved were probably younger sons, with no room at home for them. It’s the same reason people hang on in Donegal.

And to think that with the finiteness of fossil fuels and climate change, we have a shift away from the consumer economy and much more deindustrialization ahead of us, no matter where people live. What then? This is why, unlike economists, I am not dismayed by those fertility numbers.

bill clinton, oh they will just find another job, joe biden, why don’t they learn how to code, robert reich, we will run the factories of the future, gene sperling, let then eat cake, blah blah blah

lets not beat around the bush and say deindustrialization, lets call a spade a spade and say “FREE TRADE”

Free Trade.

The marketing term for how to stab your countrymen in the back, whilst robbing your country’s natural resources and markets.

Capitalism and malicious capitalists have a solution for work not being available to enrich themselves but plenty of goods being available — goods rot, people starve.

Socialism and other systems have a different solution. People LIVE and surplus goods are distributed equitably.

As a planet and as a people — a global civilization — we have no more time for goods hoarders who let people die and their goods rot unless they can get ever richer.

There is enough for everyone. It’s time to get past the politics of resentment and hoarding. There’s more than enough to do besides that which enriches billionaires, as well. I see we have too few artists and medical people, for instance. WAY too few ecologists.