By Lambert Strether of Corrente.

The original post morphed into series: Part One; Part Two. –lambert

Readers will recall the previous two posts in what became this series: My Life So Far in Writing Tools, where tools were very analog printed books, like the OED, and My Life So Far in Type, where the type that conveyed the writings was first physical (typewriters), then analog (phototypesetters), and finally digital (the AM Varityper). The transition from analog to digital began at the keyboard and ended up inside the printer, culminating in a workflow that was bits (binary digits) from start to finish (except, of course, for the decimal digits of my typing hands). At the time, these phase transitions appeared as changes in the flow of my working day, as I hopped from job to job, like Eliza hopping across the Ohio River from raft to raft of undulating, creaking ice (embarassingly, whenever I “reach for” “Eliza” I always grasp Motown’s “Little Eva.” Bad Lambert’s associational memory). In retrospect, I was being borne along on the current of enormous changes, as the work from entire industries ceased to flow, dried up, and new industries — from Silicon Valley! — came into full spate.

After several stints as a production manager, still in the printing trades, I ended up in a printshop as a part-time manual paste-up artist, because I felt I wanted to work on my writing. This once again came to nothing — my university friends had long since scattered — but for some reason I ended up at a trade show, where I saw a Macintosh. There were newsstands in those days — racks of printed magazines you could stand and read, without necessarily buying — and Cambridge (down, or up the Red Line from Boston proper) was famous for them. There I perused computer magazines, and noted with interest that there were now personal computers dedicated to doing whatever it was that the AM Varityper did (there was no name for that at this point), but smaller, sleeker, and cheaper. Hmm….

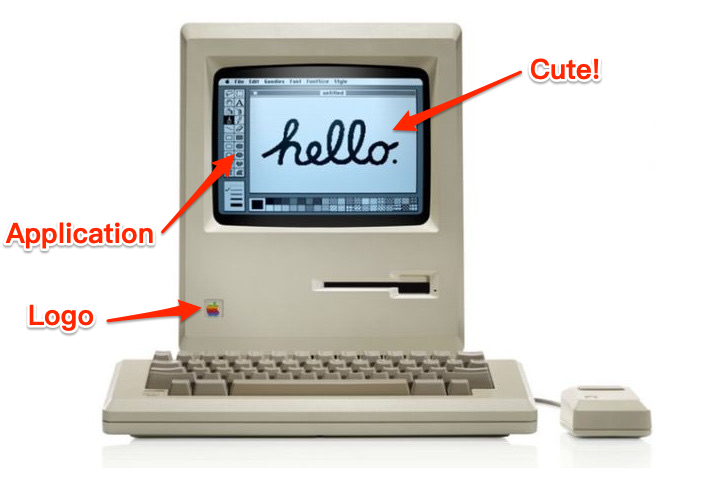

The Apple Macintosh (“Mac”) I saw was a whole new thing, different from the AM Varityper, though having all the same elements: Keyboard, monitor, disk drive, etc. It looked something like this:

There was the rainbow logo, which didn’t look corporate (the wintry, anorexic whiteout of Apple’s later thin aesthetic had not yet made its appearance). Moreover, the Mac was clearly designed; the curvaceous yet cute “Hello” reminded my of my family’s friendly and reliable VW bug (and Mac users, for a long time, tended to salute each other in passing, much like VW drivers). For another, it had what I learned were called “applications” — MacPaint, a program that allowed you to draw bits on the screen to make art, was one such, but there was MacWrite, which allowed you to do a thing called “word processing.” Best of all, there were fonts, fonts that came in Roman, bold, italic, and bold italic (all bit maps on the screen, and jagged if you looked too closely. And later I discovered that there were lovely typographic — “curly” — quotes built in, and amazingly, dashes: en, em, and even discretionary hyphens! The Mac felt like a real compositor’s case). My newsstand reading, however told me that the floppy drive was insufficient to do real work: I discovered that there were actually “tips” — an ecosystem of printed magazines, funded by Apple advertising, was rapidly evolving — on the proper way to hold a new floppy disk so you could insert it rapidly when you ejected the old one. My AM Varityper disk was large, and the drive klunky, but I never had to do that! So I waited….

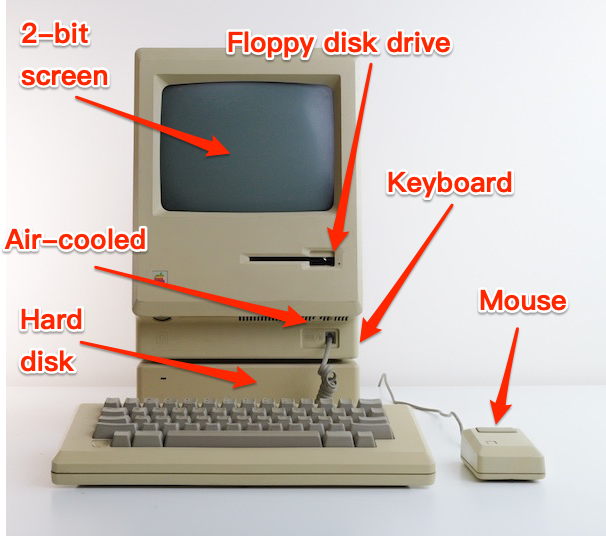

In the fullness of time, the Mac 512KE — so-called from its 512 kilobytes of RAM (my current Mac has 16 gigabytes) — came onto the market. Being still quite poor, I approached the ‘rents, and they unbelted (generously, considering my difficulties in school, and wisely, since the gift set me on the path to several real careers, including this one). I ended up with a machine that looked a lot like this (with some modifications):

As for the naming of the parts: The legendary Steve Jobs apparently hated fans, and so the Mac, like our VW bug, was aircooled. The screen was two bits, one for black, one for white (zero and one in the machine’s RAM). Looked at closely, the entire screen image was an array of black and white dots, and — incredibly! — the dots (I read) were 1/72 of an inch, just like the divisions on my pica ruler. The floppy drive took bigger disks, but I also acquired a hard disk (I forget the brand, but it held an enormous quantity of data: 10 megabytes; enough for half a RAW file these days, but enough for a lot of word processing files, at least. The keyboard was extremely odd after the professional feel of the AM Varityper, and felt odd and klunky — like most Apple keyboards, if truth be known — but at least it wasn’t mushy.

And then there was something the AM Varityper had not had: a Doug Engelbart-style mouse (from the tail-like cord, I suppose):

The mechanical mouse has a ball in its underbelly, and as you move the mouse, the ball rolls. Small rollers inside the mouse detect this movement and send signals to your computer, telling it how far and in which direction the mouse is moving. This information is then used to move the cursor on your screen accordingly

Great technology, except the ball (rubber, back in the day) picked up whatever it rolled over, and so periodically, when the mouse movements began to hitch and get random, whatever hairballs the rubber ball and the rollers had accumulated needed to be cleaned, which had an enormous ick factor; I still shudder to think of it.

I brought the boxes home to my Somerville apartment under cover of darkness, and set it up on a table I had built. Then I sat on my draftman’s stool and turned the Mac on (“booted it up”), by flicking a switch.

Nothing. In fact, for two days nothing.

On the third day, I accidentally jostled the mouse, and the Mac’s screen sprang to life! I then discovered that the machine had a version of Pong, controlled with the mouse, and for two days I did nothing but play Pong. Then I thought “Wait a minute,” stopped, and since then have never played a computer game (on my one of my machines or any other).

The fonts and the pica-friendliness of the screen led directly to what was called “desktop publishing,” where the Mac did did everything the Typesetting Department, the Art Room, and the Page Makeup Department did, inside the computer, in a single application (and if you already understood type, page geometry, and the language of publications generally, it was extraordinarily easy to become blazingly productive, which I did (thanks again to the generosity and wisdom of my parents; I didn’t need to ask again).

But this post is not about the desktop publishing branch on the path of my so-called career (even though I loved that work just as much as manual paste-up).

This post is about writing.

Having acquired a computer, I joined a computer user group and started going to meetings. The group was entirely run by volunteers. (Here we recall the recordists of the Macauley Library, and correspondents of the OED). One thing volunteers did was write (meeting reports; reviews) and so I volunteered to do that.

My difficulty in writing, whether with pen on paper, or with a typewriter, could be dubbed a sort of rathole blockage. I would start with a fine rush of words, get a few paragraphs and then a few pages in, but I would always encounter a topic where I needed to dig deeper, and then deeper, and the deeper still, and there seemed to be no way to extricate myself from the rathole and go on, and so I stopped. I could never finish anything! I was too young to know about Vladimir Nabokov, who composed on index cards, or P.G. Wodehouse, who wrote on paper sheets, and attached them with clothespins to strings hung from the ceiling [citation needed]. Both techniques permitted re-arrangement, which I needed, but didn’t know that I needed — I blamed myself for unclear thinking — and didn’t even know was possible.

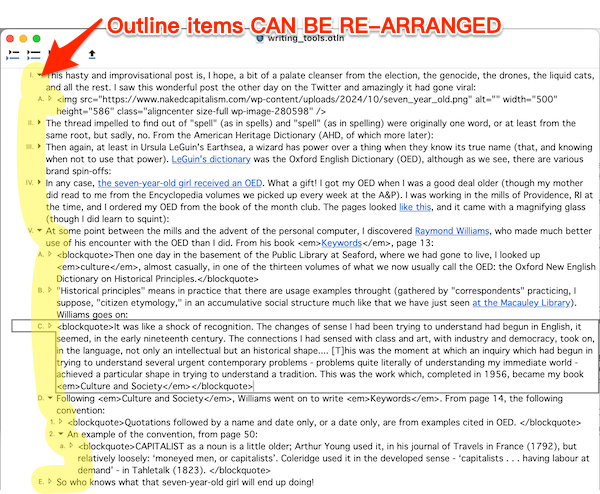

Then I discovered that there was a Mac Desk Accessory (a sort of widget) called Acta[1]. Acta was an outliner, and made outlines just as you were doubtless trained to do in school. Rather than explain what an outline is, I will present part of the outline for the first post in this series, My Life So Far in Writing Tools:

As you can see, the outline items are numbered Harvard-style (I., A., 1., a., and so forth), though I turn off the numbers (except when I want to count paragraphs), because the indentation is enough to show the structure.

The key point: The outline items can be rearranged. I could simply jot down text, in any order, fragments or complete paragraphs, as I pleased, and then polish and re-order until the work was done. That unclogged the rathole blockage! I could finish! The first time I used Acta, I finished a report. On the same day, I wrote a product review. I felt wonderful.

And so, to the extent that writing can be an art, and to the extent I have mastered it, I owe my mastery of the art to the Mac, to the author of Acta, to the digital transformation that brought both into being, and of course to many, many years of turning words into type before that[2]. I can finish!

READER NOTE

My identity is, at this point, pretty porous, now that I’ve gotten somewhat autobiographical. However, I would be grateful, dear readers, if you did not speculate on it in commments, or on the institutions and locations mentioned in these articles. There’s no point making life any easier for Google and than it already is. Thank you!

NOTES

[1] Desk Accessories went away when the Mac OS became Unix-based. The author of Acta, David Dunham, wrote the wonderfully simple Opal outliner, which is no longer maintained (and I dread the day that a so-called upgrade causes my one essential software application to fail). Microsoft essentially killed off the product category by incorporating a brutish and horrid outliner in its Microsoft Word bloatware. (I believe that in this post I am also correcting the record; neither this history of outliners, nor this one, mention Acta or Opal.

[2] Which is one reason I em use a Mac, besides the fact that the user interface and keyboard shortcuts are etched into my muscles, my nerves, and my brain.

What a charming post! I was in high school during the mid-90s, and we still had some Apple IIe’s in the computer lab that were my first experience with print layout (for the school yearbook). My parents were thrifty working class people who had finally gotten a computer in 1995 – a cheap Acer running Windows95 – and I was quite enamored with the entire Apple integrated application and os aesthetic but could never afford one until well into my 30s, in the featureless metal slab era. I spent hours on IRC in my teens on the Windows machine at home, talking with strangers and learning how to use a command line, and became a Linux lifer by my early 20s. I originally got deep into Linux because of the customizable desktop environments – I was obsessed with trying to recreate that first Apple experience without the cost (I never succeeded of course, greater minds than mine have tried and failed).

I stan for the mechanical mouse! Cleaning that ball is humanizing, like cleaning your belly button.

But seriously I have very early memories of my father doing music production on software called Performer which ran exclusively on System 6.0.3 at the time. Thus, an SE was my first computer. Same form factor as the 512 and the Plus. I find the dithered monochrome display far more expressive than today’s overwhelming resolutions.

The best part of the Mac world was by far the mess of weird shareware that floated around on 3.5′ floppy. Truly bizarre things like Baby Smash or Jared, Butcher of Song. Masterpieces like The Manhole, Dark Castle, or Glider. All made by little hobbyists who were simply part of what was basically a demoscene. And writing software for System 6 was Hard. The Mac was notoriously developer un-friendly which partly explained the lack of PC software ports. Objective-C was and is a truly awful language. But for some reason the Mac is what put me on the path to coding.

The Macintosh SE had an overwhelming impact on my career and life in general, and I still get misty eyed occasionally when I hear that startup chime.

I found database development on system 7 quite straightforward and pleasant.

And there were serious attempts at enabling “citizen developers”: AppleScript and HyperCard come to mind immediately.

On the other hand, their first VR software development environment (the name of which escapes me now) was truly nightmarish, forcing me to use a unofficial and undocumented command line environment. But in the end, it worked…

Steve Browner:

As a design student, there were two publications I subscribed to. The first, PRINT, had a student discount I could afford on my ramen-noodle budget. The second was better yet—it was free, including shipping. The publication was called U&lc, an acronym for upper and lower case, and was a result of 1974 legendary designer Herb Lubalin’s brilliant idea: What better way to display the myriad typefaces for the International Typeface Corporation (ITC) than with a quarterly magazine? (Though the tabloid-size format was really more like a newspaper, and was even printed on newsprint, with a fold down the middle.)

Neal Stephenson:

See org-mode.org for Emacs’s thermonuclear outliner.

Yes, and the org-mode exports also to ODT which is the format for Libre Office writer. I love the story behind Libre Office.

I am glad someone else finds Emacs Lisp aesthetic. And the idea behind it is genius. I did some tables in org-mode to calculate prices for my taxi services just to prove a point. And the ever helpful community on stackexchange helped me with the Lisp expressions for my tables. I had an answer in matter of hours !

I come from the era where “Byte” magazine was a must-subscribe. The sci-fi author Jerry Pournelle was a columnist, which for me was a monthly must-read. But as someone who wanted to tinker and hack, the IBM PC with its circuit board schematics, full BIOS listing, and DOS api manual was where I was at. Had absolutely zero interest in anything Apple, and to this day my house is an “Apple-free zone”.

But then I got into OS/2, light years ahead of Gates, but TPTB at IBM decided not to support it and in the end I had to go to the dark side with Win 98. (USB interface was the proverbial straw to break the camel’s back as OS/2 Warp didn’t easily support drivers for it).

OS/2 Warp did come with an IBM-built browser, but that was quickly terminated and instead IBM provided Mosaic spin-off “Netscape” which to this day I use its child Firefox (was Communicator then Sea Monkey then Firebird but a trademark dispute ended that).

But the publishing wars between Apple and Adobe and MS I didn’t really participate in. I’m just glad that now with OTF fonts and unicode we pretty much have cross-platform commonality.

I always enjoyed cleaning the rubber ball. Much more fun than trying to hook cat fur out of the laser niche at the base of my current mouse.

Incidentally, long, long ago in the late 1980s I was a political activist in our Media subcommittee, typing out material and then laboriously typesetting it for pamphlets (I wrote my Masters on a manual typewriter). In 1990 the activist across the road bought a word processor and casually showed me how to do the whole multi-hour typesetting refonting thing in about ten minutes.

My life would have changed for the better, except that I moved to northern Natal where there was no real need for pamphlets if you had an AK or a panga. (I had neither so I gave up politics.)

Hello,

My first attempts to write something longer than a 20 page article lead me to try out different editors and writing software….

It is the Org-mode for Emacs editor that I love the best ! Because the outline is so simple and it collapses…in nice colors too. Each header 1, 2, 3 in different color nicely indented. I have a “Tango” theme in my Emacs on dark grey background and colored text.

It works well for writing websites too. With a simple command it exports text with all the headings, images, links etc. to HTML. Oh, and it has an “import” function. Very simple, so it is possible to maintain separate files and make them come together in a single document with few lines of text – commands.

In fact, Emacs handles also my e-mails with Mu. Impressive. It can search in a split second for a word or an expression through thousands of e-mails dating back years. This editor has also a huge ecosystem of developers and a philosophy that goes with it. Thank you Richard Stallman. AND it is light and fast.

re: identity issue

Past WE I met friends returning from the Frankfurt Book Fair, where – unsurprising – business has turned into a never-ending tragedy.

We then came to speak about high school reunions and I made clear I had never attended such a ghastly event and would never want to. “But are you not curious? Don´t you look people up online?”

I was abhorred of imagining doing that. One thing I never did is “googling” people I used to know. After all this was impossible in the past. And life worked (better) without. Why start doing it now?

Everyone turns into a search item and commodity of our world of personal vanities and career interests.

I mentioned John Steinbeck´s “Travels With Charley” to explain why. I had read it in my youth and a few things had stuck with me. Steinbeck I believe (now, this is almost 40 years ago) says he had 2 rules when talking to strangers who he would meet when crossing the States.

One was to never ask people for their names. The other, never ask them about their job. He would entirely leave that to the others. Whether they would be willing to talk about those things or not.

I found this wise since.

It was aircooled, just like most of computers in existence, including those with fans.

Black and white means 1-bit color.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Color_depth#List_of_common_depths

I understand the ick factor of the mouse – but – inverted. Yes, I am a trackball user. I have come to favor the Kensington for the last 20 years, where the ball strongly resembles the size and heft of the balls on a pool table. Something very sensual to flicking the cursor across screens from one extreme to the other as the rotatitng mass keeps it moving. The trackpad of the keyboard I write with (laptop versus workstation) is an entirely different experience.

And wordprocessing these days is using Microsoft Word, or more so a tool called WordPress, an open source software package for outputting content to blog posts.

No outliner with WordPress, I have to do that in my head. But new-ish to the WordPress ecosystem is something called Gutenberg. This makes reordering quite easy. And on the PC, several tools, one called InDesign with which I do layout for manuals by Adobe, who have been both a blessing and a curse. InDesign is one of three of their tools I rely on. The others being Photoshop (a tool for dealing with photos) and Illustrator for sketches and raw art/drawing, all three of which I subsequently deliver to my printers. These typically being the 4-color brochures, as well as the large images for the outbox or the small images for the folded cardboard inserts, both for my products.

Odd how writing leads some of us through life.

Fellow trackball addict here (big ball Kensington “expert” model, of course ; )

I did a lot of writing and editing for my résumé clients but the most important thing was getting their information properly organized. Then, after getting everything into its proper place, moving a few things into more prominent places. Lists have sweet spots and dead zones. Chronologies can be manipulated:

EXPERIENCE – EDUCATION – PERSONAL

or

RELATED EXPERIENCE – EDUCATION – ADDITIONAL EXPERIENCE – PERSONAL

or

RELATED EXPERIENCE – RELATED EDUCATION – ADDITIONAL EDUCATION – ADDITIONAL EXPERIENCE

Readers may be surprised to see that your lead job listing ended in 2019 but then they look more closely and realize you’ve been doing unrelated work more recently. The real benefit is that many readers won’t catch the dates until they’ve spent more time reading (aka investing time in your application).

How you organize your information is very important. If Yves and Lambert flipped the plants and animals in their links LINKS and WATER COOLER posts, it would probably change how we read those pages. I’m guessing clicks would either go up or down but honestly am not sure which.

My work was the most mundane application of Lambert’s computer outlining imaginable. Outlining is key to good writing and computers make outlining much much much easier. You can write with a number two pencil and a stack of paper but good luck with longer projects like novels or scripts.

The patriarch had some type of programmable word processor with a flip-up viewer – you would type on the viewer, do your edits, then it would pass documents (as i recall, it was a rather constipated process). We kids did a thorough job of destroying it by banging on the keys and messing with the viewer. I don’t think he minded. That much. Thanks mom.

My college roommate fashioned himself a writer (and is now professionally), and would often compose on a typewriter. I thought it was fussy and irritating, but not for the clickity clack, i just thought he was being pretentious.

I struggled graduating from pencil and paper to the screen, but my teachers appreciated it because i write in a terrible uneven scrawling script. I have thus far squandered the legibilty dividend – inversely correlated to making myself understood, it often seems.

lolz.

> The fonts and the pica-friendliness of the screen led directly to what was called “desktop publishing,”

I believe the LaserWriter was another necessary condition for the start of the desktop publishing era. It just worked and did so very well. The results you could get with that computer and printer were persuasive.

Huge Outliner devotee here. Moving sections and adding new details upon details at any point really make these tools great for organizing ideas. Hiding detail sections is also really useful. I recall one outliner where you could zoom into a level and see that full page, like collapsing outer items as well as inner items.

In the late 80s forr 5 years I did the ‘Office’ apps domain in computing, i.e . Word processing, spreadsheets, image processing and presentations for Digital Equipment CO. All in a multilingual and multinational sphere. It meant jaunts around Europe meeting up with the translation teams. Happy Days.

The big things that amazed me were reverse video as a means of highlighting text and full justified text. It looked soooo elegant.

Until one day I noticed the gappy aspects. And that took off the sheen from justified text for me.

Remember Visicalc, Paradox, Word Perfect, and Harvard Graphics ?

I started with an Apple II, but went to the dark side when it came time to make money.

WordPerfect was SO MUCH better than Word. Ditto Improv v. Excel.

I remember Acta. In those years, I also struggled with writing, and finding tools that could actually help became akin to the holy grail of desktop computing. Word processors made infinite revision easy — no more hardcopy drafts, or at least far fewer —, but these early WPs seemed quasi-useless for outlining, writing arguments, etc.

My own “conversion” happened in the 1970s. Learned to code on ASR 33 Teletypes attached to PDP-8 vintage machines in the early 70s. Terminals with CRTs existed, but mostly for mainframes and 80 x 24 characters only. First encounter with a bitmap display and GUI was a Xerox Alto around 1976. This was simply a quantum leap from the ASR 33, and there was no going back. For word processing, there was BRAVO, written by Charles Simonyi (who later defected to Microsoft and led the development of MS-Word). Bravo was very slow, but defined the whole WYSIWYG genre: multiple fonts, paragraph formatting, page/section breaks, footnotes — it was all there.

Around 1982, I took a job at Xerox, where I learned a lot about digital typesetting, laser printers, etc. The then-current Xerox 7000 printer was 300 dpi (5x screen resolution at 72dpi), but could print complex documents, bitmaps, everything, and at two pages a second. It used the predecessor to PostScript (another Xerox technology that later walked out the door). Personal computing was taking off, but the early offerings were weak sauce. The Apple II, for example had dismal graphics.

It became clear that Xerox had no interest in the mass market. The Alto had been completed in the early-mid 70s, and the company then dithered nearly a decade. In the early 80s, Steve Jobs made his infamous visit to PARC, and soon productized what X would not. Sometime in 1983, I saw a news spot about the announcement of the Apple Lisa, showing the bitmapped GUI, mouse, menus, etc.; my first thought was: “ JFC… FINALLY.” I eventually left Xerox, departed Computer Science for the Humanities, and later bought a Macintosh II (can’t believe I spent $7000+ on that, but it served me for years thereafter).

All the early Mac WP apps seemed even slower than BRAVO on an Alto. I eventually just came to use very simple tools for writing — and still do most writing with macOS TextEdit —, and only use Word or LibreOffice for the final document.

Watching this tech slowly mature has been both interesting and often frustrating (e.g. the rise of horrible desktop bloatware that’s all about vendor lock-in), but like Lambert, I ultimately became more interested in writing than the tools themselves.