By Lambert Strether of Corrente

This post morphed into a series: Part Two; Part Three. –lambert

This hasty and improvisational post is, I hope, a bit of a palate cleanser from the election, the genocide, the drones, the liquid cats, and all the rest. I saw this wonderful post the other day on the Twitter and amazingly it had gone viral:

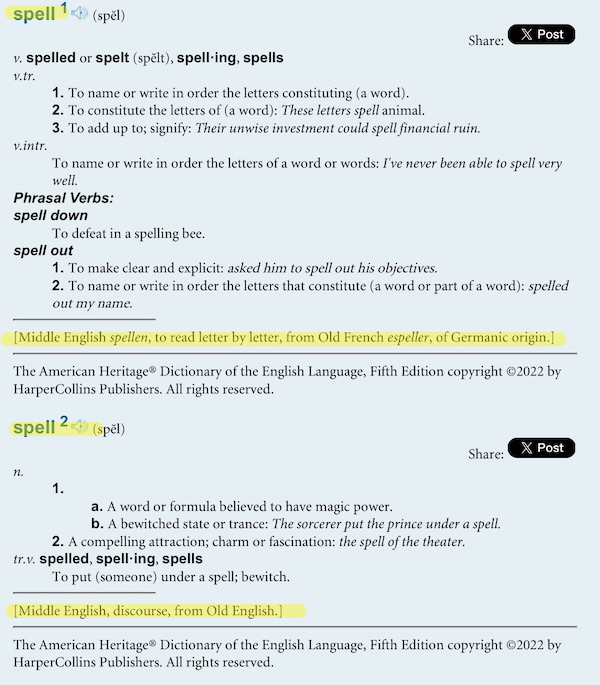

The thread impelled me to find out of “spell” (as in spells) and “spell” (as in spelling) were originally one word, or at least stemmed from the same root, but sadly, no. From the American Heritage Dictionary (AHD, of which more later):

Then again, at least in Ursula LeGuin’s Earthsea, a wizard has power over a thing when they know its true name — especially when they know not to use that power — and how can you know a true name if you can’t spell it? LeGuin’s dictionary was the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), although as we see, there are various brand spin-offs (Compact, Shorter, etc.):

All my life I have written, and all my life I have (without conscious decision) avoided reading how-to-write things. The Shorter Oxford Dictionary and Follett’s and Fowler’s manuals of usage are my entire arsenal of tools.*

* Note (1989). I use Fowler and Follett rarely now, finding them authoritarian. Strunk and White’s Elements of Style, corrected and supplemented by Miller and Swift’s Words and Women, are my road-atlas to English, and have never led me astray. A secondhand copy of the smallprint Oxford English Dictionary in volumes has been an infinite source of learning and pleasure, but the Shorter Oxford is still good for a quick fix.

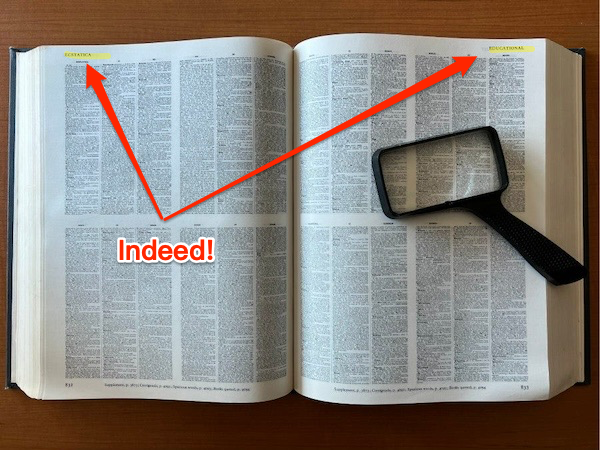

In any case, the seven-year-old girl received an OED. What a gift! I got my OED when I was a good deal older (though my mother did read to me from the Encyclopedia volumes we picked up every week at the A&P). I was working in the mills of Providence, RI at the time, and I ordered my OED from the Book of the Month Club. The pages looked like this, which is why it came with a magnifying glass (though I did learn to squint):

The OED, I thought, would be useful to me in my vocation as an adult poet, though I discovered too late I had nothing to say, at that age, in that medium. Nevertheless, I lugged it about with me until I lost it with the first of my lost book collections.

At some point between the mills and the advent of the personal computer, I discovered Raymond Williams, who made much better use of his encounter with the OED than I did. From his book Keywords, page 13:

Then one day in the basement of the Public Library at Seaford, where we had gone to live, I looked up culture, almost casually, in one of the thirteen [now twenty (!!)] volumes of what we now usually call the OED: the Oxford New English Dictionary on Historical Principles.

“Historical principles” means in practice that there are usage examples throughout (gathered by “correspondents” practicing, I suppose, “citizen etymology,” in an accumulative social structure much like that we have just seen at the Macauley Library). Williams goes on:

It was like a shock of recognition. The changes of sense I had been trying to understand had begun in English, it seemed, in the early nineteenth century. The connections I had sensed with class and art, with industry and democracy, took on, in the language, not only an intellectual but an historical shape…. [T]his was the moment at which an inquiry which had begun in trying to understand several urgent contemporary problems – problems quite literally of understanding my immediate world – achieved a particular shape in trying to understand a tradition. This was the work which, completed in 1956, became my book Culture and Society

Following Culture and Society, Williams went on to write Keywords. From page 14, the following convention:

Quotations followed by a name and date only, or a date only, are from examples cited in OED.

An example of the convention, from page 50:

CAPITALIST as a noun is a little older; Arthur Young used it, in his journal of Travels in France (1792), but relatively loosely: ‘moneyed men, or capitalists’. Coleridge used it in the developed sense – ‘capitalists . . . having labour at demand’ – in Tahletalk (1823).

So who knows what that seven-year-old girl will end up doing!

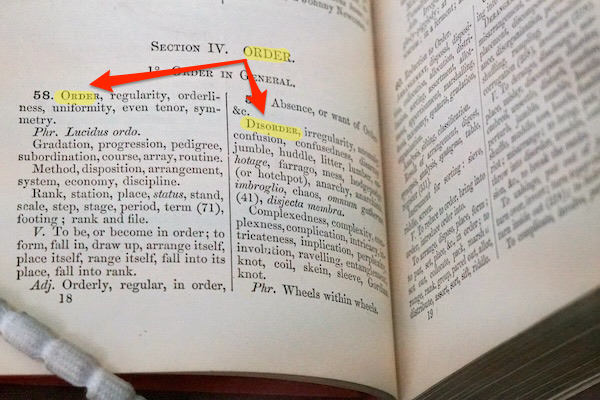

However, my very first reference work — I was a teenage poet, and did have things to say, at that age — was (image via James Moss) a Roget’s Thesaurus, the kind that we now see as old-fashioned. It looked like this:

As you can see, Roget’s organizes words into classes (“Order” is #IV of six). Within each class, opposing concepts are placed, well, opposite each other; as we see, Order vs. Disorder, or “progression,” “pedigree”, “economy,” and “station” are on the left, and the sinister “irregularity,” “huddle,” “farrago,” and “disjecta membra” are on the other. Quite unlike Newspeak, where “‘un–’ is used to indicate negation, as Newspeak has no non-political antonyms.” Now, of course, I’ve forgotten all those youthful follies, but the pleasure of looking from left to right for an opposite that is not quite opposite — is “complexity” really the opposite of “regular”? — and turning each word over in my fingers remains.

Sylvia Plath — an actual, adult poet — had used a Roget’s (image via Peter K. Steinberg), so I went looking, and found (image via Peter K. Steinberg) it had been sold at auction (“Lot 309”). Here it is, complete with her underlining:

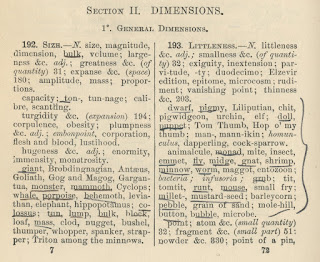

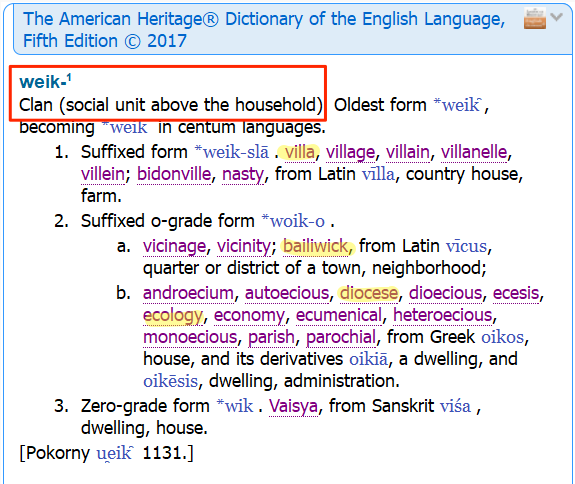

One more: Shortly after I discovered Roget, I discovered the AHD Dictionary of Indo-European Roots:

Fascinating that “villa,” “bailiwick,” “diocese”, and “ecology” (!!) all branch out from the same root. Endless forms most beautiful!

The complex data structures in all these works — historical principles (OED), classification systems (Roget), tree structures (AHD) may not have inspired great poety in me, but they certainly prepared me for a life of symbol manipulation, as the PMC manqué that I am!

Concluding, I highly recommend that you give the seven-year-olds in your life — as well as the poets, the wannabe poets, the autodidacts, or simply those who want to master the wondrous English language — reference works like the Oxford English Dictionary. And not the online versions, which are dumbed down, hard to use, and track you. Get physical, durable, endurable books. Go to a second-hand bookstore and get books, the older the better. Maybe you’ll hit the jackpot and find all twenty volumes of a full-size OED!

What a wonderful essay.

If I was a suspicious person, I could think that project to create Newspeak is not a fantasy.

I write every day in English. I consult wordhippo.com about 20 times a day. Down below someone says, “without a couple dozen words that mean almost the same thing, your writing lacks depth”. I agree, but my mind does not recall them.

Wordhippo might have only synthetic definitions, but there are synonyms and antonyms. It is fast to move between them. Using it is priceless. It is always open on one tab.

I sometimes use a hardback to look up words in a foreign language. It is very cumbersome, and when I close the page, I might realize I didn’t really retain it. I have worked with many of the on-line translators and have translated millions of words (many books) over the years. With some languages they are very good, with others there is little comprehension.

Don’t be worried about on-line vocabulary aids.

.

I was a precocious brat and had a copy of the Shorter Oxford English Diction in two volumes (A – Markworthy; don’t remember the other). I adored it, its tiny costive abbreviations, information-dense formatting and historical usages. I also had a copy of Roget’s, which was equally adored.

A very saturnine English teacher asked my mother at parents’ evening if I had swallowed a dictionary and she could only reply yes.

I don’t think either of my children has ever used a physical dictionary….

“Marl-Z” just came to me lying on the sofa. I will have to go back to the family house to check though….

https://accounts.smccd.edu/bellr/readerlearningtoread.htm

I saw that the best thing I could do was get hold of a dictionary—to study, to learn some words. I was lucky enough to reason also that I should try to improve my penmanship. It was sad. I couldn’t even write in a straight line. It was both ideas together that moved me to request a dictionary along with some tablets and pencils from the Norfolk Prison Colony school.

I spent two days just riffling uncertainly through the dictionary’s pages. I’d never realized so many words existed! I didn’t know which words I needed to learn. Finally, just to start some kind of action, I began copying.

In my slow, painstaking, ragged handwriting, I copied into my tablet everything printed on that first page, down to the punctuation marks.

I believe it took me a day. Then, aloud, I read back, to myself, everything I’d written on the tablet. Over and over, aloud, to myself, I read my own handwriting.

I woke up the next morning, thinking about those words—immensely proud to realize that not only had I written so much at one time, but I’d written words that I never knew were in the world. Moreover, with a little effort, I also could remember what many of these words meant. I reviewed the words whose meanings I didn’t remember. Funny thing, from the dictionary first page right now, that “aardvark” springs to my mind. The dictionary had a picture of it, a long-tailed, long-eared, burrowing African mammal, which lives off termites caught by sticking out its tongue as an anteater does for ants.

I was so fascinated that I went on—I copied the dictionary’s next page. And the same experience came when I studied that. With every succeeding page, I also learned of people and places and events from history. Actually the dictionary is like a miniature encyclopedia. Finally the dictionary’s A section had filled a whole tablet—and I went on into the B’s. That was the way I started copying what eventually became the entire dictionary. It went a lot faster after so much practice helped me to pick up handwriting speed. Between what I wrote in my tablet, and writing letters, during the rest of my time in prison I would guess I wrote a million words.

I suppose it was inevitable that as my word-base broadened, I could for the first time pick up a book and read and now begin to understand what the book was saying. Anyone who has read a great deal can imagine the new world that opened. Let me tell you something: from then until I left that prison, in every free moment I had, if I was not reading in the library, I was reading on my bunk. You couldn’t have gotten me out of books with a wedge…

I always kept a dictionary and thesaurus, at hand, when writing. I still have our huge, leather-bound dictionary from the turn-of-the-century. I spent many a happy hour, as a child, poring over the colored ‘plates’ in the back with their beautiful illustrations of cultures around the world.

Bravo, sir!

Words and meaning, when used with skill, allow us to inspect, inquire, and inspire That’s for the stroll, Lambert.

Without two dozen words in mind that mean what you intend

You lack the depth and width to know which way which words will bend

To wrap and couch the thought that’s waiting to take verbal shape

Which can then carry it into another mind’s landscape

And plant itself precisely where and as you have foreseen

Where it will sprout and grow a tree that’s huge and grand and green

Antifa, you have a way with words!

Indeed!

Coincidentally, I asked my soon to be 11 y/o grandson the meaning of facile, today. His Merriam-Webster’s Elementary Dictionary skipped from facial to facilitate and thus, he resorted to an online source. So while this dictionary is still fine for my 8 y/o, my oldest has outgrown it. Anyway, I’ve made an offer on a better Websters nearby via Facebook Marketplace and await a response. May go to a used bookstore if nothing turns up.

Over the course of (most of a lifetime it turns out) of combing rummage sales and flea markets I’ve observed that library book sales consistently have had dictionary sets on offer. Some libraries sell books year round and have a section dedicated to this. Others store their books awaiting the next sale. You might try asking your local librarian if they have any they are getting rid of. Good luck!

As a follow-up to this, there’s a delightful little book by Ammon Shea, who read the entire OED cover to cover, and wrote about his experience: Reading the OED: One Man, One Year, 21,730 Pages.

I still have my Dad’s Webster Collegiate Dictionary from the 1950s — one of my most cherished possessions.

I have a dictionary which was given to me for high school graduation by my neighbor and sixth grade teacher. She taught me how to diagram sentences which has been helpful in many ways. Mrs. Porter was an important influence.

I have a dictionary (concise shorter) at work and my wife has something similar at home. (She uses a thesaurus but I’ve always scorned such fripperies, just the way I refuse to get flu shots because I’m strong and free, if sniffly and achey). The most wonderful thing about it is that these days I read a word and suddenly realise that for all my life I’ve assumed I knew what it meant and that actually I don’t, so I rush to the dictionary — or else, like Lambert on “spells” come across a word and wonder what the etymology of it is. In both cases I’ve never been disappointed; exploring meaning and etymology is like exploring an endless rain-forest of meaning.

On a related topic, however, given Lambert outing himself as a rhymesmith, here’s D J Enright on the Good Old Days and on the uses of characters:

The Typewriter Revolution

The typeriter is crating

A revlootion in peotry

Pishing back the frontears

and apening up fresh feels

Unherd of by Done or Bleak

Mine is a Swetish Maid

Called FACIT

Others are OLYMPYA or ARUSTOCART

RAMINTONG or LOLITEVVI

TAB e or not TAB e

i.e. the ?

Y, this L

Nor-my-outfit

Anywan can od it

U 2 can be a

Tepot

C! *** stares and /// strips

Cloaca ns+ –

Farty-far keys to suckcess!

LSD & $$$

The typewiter is cretin

a revolution in peotry

“ “ All nem r = “ “

O how they £ away

@ UNDERWORDS & ALLIWETTIS

Without a.

FACIT cry I!!!

The linotype is fickle

She breaks down twice a day

O but when she hits the matrix

She will steal your heart a-w-a-a-y

(from memory)

“… are on the left, and the sinister “irregularity,” “huddle,” “farrago,” and “disjecta membra” are on the other.”

What a wonderful inversion of values that sentence describes. Just like our politics; Left is Right and Right Left.

When we were living “out in the woods,” and the children were small, we found a one volume giant Oxford Dictionary at a library discard sale. The thing weighs about ten or twelve pounds. Next up we found a single volume Complete Works of Shakespeare. Combining that with a conscious decision to limit the children’s exposure to electronic media and we come out the other end of the process with real people.

Today, Skinner’s Box would have full wall video screens on all inner surfaces. Come to think of it, our society has become such a construct for the young. Every available surface becomes a screen to stare at, and which stares right back. Nietzsche was right, we are the Society of the Abyss.

Stay safe. Remain ever vigilant.

A long time ago when we stared into the abbeys, we thought that there were eldritch monsters within staring back. So we built our own digital abbeys and now we learn that within it are corporations who are definitely staring back

A long time ago when we stared into the abbeys, we thought that there were eldritch monsters within. So we built our own abbeys and now we learn that within it are corporations who are definitely staring back

Long ago, my office mate subscribed to something in order to get the included gift of OED with tiny print and a magnifying glass. It might have been 3 books. He was an Oxford english grad, and would spend time looking for earlier uses of words in their ancient stacks while a student.

My kids recall the joy of going to grandma’s house. One fun memory was of using that OED magnifying glass to marvel at the volumes and words. She was tickled by that, knowing that another book and word generation would live on.

When I was a graduate student, I remember being very envious of a fellow student and her husband who could afford such riches.

An AHD was a Christmas gift in 1976. It still seems to have been the ideal reference source. Encyclopedic — not just words, but people, too, and more, plus photographs as needed. Illuminating usage notes. The etymologies were a window into history, change, and the commonality of language and ideas. Just the chart of language families was compelling. The editors kept the language’s naughty bits rather than yielding to scolds (I still delight at the memory of first learning the etymology of snafu). And it was easy to read. Unlike your average Websters, the AHD font (Helvetica?) was clear and large enough to read without a magnifying glass, the kerning so humane. The layout gave the brain room to breathe. I wore it out, and I wish there were another like it.

Still my favorite reference book (1st ed., © 1969, bought right after I read a review), and for all the reasons you cite. I don’t write enough to have worn it out and hope it will last as long as I. Perhaps I’d forsake it if I stumbled across an irresistibly-priced Compact OED, but I’m not so sure …

Poets cast spells not by the words, but by rhythm and combination of words. Is your word the same as my word? Not at all! What is underneath the words! Look at this poem! No dictionary needed and it is still being read after 1200 years! Poems like Koans were meant to get you out of your head, but this is where we are? Shame…

Where’s the trail to Cold Mountain?

Cold Mountain? There’s no clear way.

Ice, in summer, is still frozen.

Bright sun shines through thick fog.

You won’t get there following me.

Your heart and mine are not the same.

If your heart was like mine,

You’d have made it, and be there!

– Han-shan

I go to my AHD, which I’ve had since 1972, for etymologies and general browsing; it’s a joy!

How strange to stumble on this today. I am packing up various belongings for eventual shipping back to Europe, including papers and books I retrieved from my father’s office after his death 5 years ago. He had a wonderful room full of photos, art, memorabilia and books from throughout his research career. Among them was the compact OED shown above, complete with the magnifying glass. It is heavy and frankly I doubt I would consult it very often but I have so many memories of seeing it on his shelf…

He was an absolute fan of Strunk & White; I have his original hardback edition, one of the earliest printed, and he bought the paperback copy (3rd Edition) in bulk and gave them to his students at the start of each year. His own scientific papers were beautifully written. Whilst packing up things here I found one of the paperbacks in which he wrote “for bedside reading” in 1989.

Thanks for the memories.

For those Francophiles, consider the Dictionnaire Robert as an authoritative source. My French friends were teachers, institutrice and professeur, and had both the Grand and Petit editions. They were of the opinion that the Larousse just would not do.

Perhaps readers can opine on references in other languages, too?

For me, my dictionary was the 1966 World Book encyclopedia, hopelessly stuck in Project Gemini.

Having read it from Aachen to Zydeco, it introduced me to non-English words along with all the usual suspects in our lingua franca.

What was great about an encyclopedia, it gave you a concise story of somebody, somewhere or something.

Same here. Somehow we ended up with three sets of encyclopedia’s growing up and there was always something there to discover or research. They showed that there was a whole world just over the horizon.

I still have the 1960 World Book Encyclopedia I WON by asking an interesting question in the “Ask Andy” section of the local newspaper.

(I was 10 years old.)

I remember reading one volume at a time over a long period.

What a world of exploration!

I’ve never had the urge to give it away.

My first thought in reading that twitter thread was who inspired that little girl! I had teachers who did that for me and can conjure them up right now. They were the ones who could move a young person to action and gave full permission to go ahead, check it out! And report back – share what you found with the rest of us. It prompted me to run downstairs and grab my old college Funk & Wagnalls and Random House dictionaries and remember (way) back to my Shakespeare and english classes at Hunter College. Really enjoyable Saturday morning read Lambert, stirred my imagination and memories.

Also, in clicking on LeGuin’s Dictionary link to Stan Carey article found this priceless gem on empathy from LeGuin:

If you deny any affinity with another person or kind of person, if you declare it to be wholly different from yourself – as men have done to women, and class has done to class, and nation has done to nation – you may hate it or deify it; but in either case you have denied its spiritual equality and its human reality. You have made it into a thing, to which the only possible relationship is a power relationship. And thus you have fatally impoverished your own reality. You have, in fact, alienated yourself.

Absolutely delightful, thank you so much.

My favorite nonfiction writer, John McPhee, recommends the 1913 Edition of Webster’s Dictionary. It is online at https://www.websters1913.com/

And here’s how I found out about it:

You’re probably using the wrong dictionary

Someday I’ll buy the actual book. At the moment, there’s one on e-bay for $224.99

Fowler authoritarian? One might expect authoritarianism from a turn of the (20th) century English schoolmaster-grammarian but I find his approach wonderfully liberal, in spite of all the learning behind it. What I most like about him is his belief that strict adherence to the rules shouldn’t get in the way of clear communication. As one example (which I now can’t find – so maybe I’m remembering it wrong), he believed a split infinitive was allowable and in fact preferable in cases where avoiding it would lead to excessively long, circuitous locutions.

He also had a passage where, in illustrating the ‘muscularity’ of simple speech, he contrasted the clarity and power of the first few verses of the Book of Genesis, where words of more than one syllable are kept to a minimum, with the promiscuously polysyllabic perambulations of an excerpt from a governmental policy statement. Wish I could find that one again.

and when writing/speaking (and singing!) in French there’s Robert and Micro-Robert.

I think it was my reading that Nietzsche was a philologist which led to my discovering the existence of OED.

Once discovered, I recall spending all of my university years parked in front of the 20 volume set in the reference section of the library, and I wrote so many of my essays from nearby. I think it was the greatest learning sprint of my entire life, I was able to trace the origins of so many ideas and concepts, had so many eye-opening moments, one clue led to others, it was one non-stop revelation after the other.

I should revisit that library, see if the volume is still there, carpet still worn thin, perhaps there will be bookmarks I placed.

Greatest gift indeed.

Thanks for this essay. It is nice to know that there still seven years olds who read dictionaries. Wife and I went to an estate sale a few months ago. She picked up a solid oak (standing) dictionary stand. The price was a fraction of what materials needed to fabricate it would cost, and they included the 2nd edition of Webster’s Unabridged English Dictionary (1979) for free. I am refinishing the stand for her. The dictionary and its stand will be her Christmas gift to our grandson when he is a bit older. Hopefully he will grow to appreciate it.

A lovely delve!

Peak Roget was the Third Edition from 1966. Indexed words have synonyms listed in category order, rather than alphabetical.

I have given Mogilner’s Children’s Writer’s Word Book to both young and old. Synonyms are indexed to grade level, which is great for Explain Like I’m Five, and Explain Like I’m A Fifth-Grader.

My mother put by father’s Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary Sixth Edition next to the toilet, and on those days I didn’t want to go outside, I wouldn’t finish up until I had learned a new word.

I have a Websters New International Dictionary from 1913. The print is very fine and the binding is shot but I still occasionally consult it to supplement more convenient on-line dictionaries. It was used in the late 1940’s. when I was a small child as a bolster on my seat to elevate me at the dinner table. Osmosis is a favorite word.