By Sören Karau, senior economist in the economics department (Balance of Payments, Exchange Rates and Capital Markets Analysis) at the Deutsche Bundesbank, and Johannes Fischer. an economist in the economics department (Balance of Payments, Exchange Rates and Capital Markets Analysis) at the Deutsche Bundesbank. Originally published at VoxEU.

There is large uncertainty around the economic effects a second Trump term would have. This column assesses the potential implications of Trump winning the upcoming election through the lens of financial market participants. The authors find that investors associate a higher likelihood of Trump winning with adverse supply-side effects on net. In the US, an increase in the prospects of a Trump victory on betting markets is associated with lower stock prices, higher interest rates, and higher market-based inflation compensation. These inflationary pressures are mirrored on the other side of the Atlantic by an increase in euro area inflation compensations.

Some of Donald Trump’s policy proposals could have profound macroeconomic implications, but there is large uncertainty around the (net) economic effects a second Trump term would have. For instance, would the US dollar appreciate due to new tariffs, or would it fall in the face of Trump’s repeated vocal opposition to a strong dollar? And what would a Trump victory mean for US growth or the disinflationary process underway in both the US and the euro area? As the election draws closer, this uncertainty has already led to heightened volatility in financial markets, as documented by Albori and coauthors in a recent VoxEU contribution (Albori et al. 2024). Extending their analysis, in this column we use betting market data in a VAR model to assess the economic implications of a second Trump term from the perspective of financial market participants.

Measuring Trump’s Victory Odds Using Betting Data

We directly measure the market’s evolving assessment of Trump’s victory prospects using data from prediction markets. These markets allow participants to bet money on certain events, including election outcomes. As with other financial market prices, betting quotes then contain all sorts of information that might affect the outcome of the bet, and have been used by Moramarco and coauthors to quantify political risk in a Vox contribution (Moramarco et al. 2020). For our analysis, we use implied probabilities of a Trump victory in the upcoming US presidential election from PredictIt and PolyMarket, as averaged and provided by Bloomberg.

Relative to election polling data – which were used by Albori et al. (2024) – betting odds come with several advantages. First, they account for the particularities of the US electoral system such as the Electoral College.1. An improvement, say, in polling numbers does not necessarily translate into better chances of actually winning the election.2. Second, polling data are gathered over several days and published with a lag. 3. In contrast, betting odds respond to election-relevant news almost immediately in an information efficient way.

However, the odds of a Trump election win, and by implication betting quotes, will generally respond to all sorts of news and economic developments, giving rise to an identification problem. For instance, the publication of surprisingly high US inflation readings might lower the odds of a Democratic win because they could signal continued price pressures that weigh on the current administration’s perceived economic performance. To the extent that an inflation surprise also signals more restrictive US monetary policy, asset prices might fall. Therefore, an observed co-movement of betting odds and asset prices is not necessarily informative about what we are ultimately interested in, namely, the causal effect of changes in Trump’s likelihood to win the election, as interpreted by financial markets.

We overcome this identification problem by exploiting the real-time nature of betting quotes. Specifically, we measure the high-frequency movements of Trump betting odds around key election-related events (see Table 1).4. These events clearly affected the markets’ assessment of the likelihood of a Trump victory, but were independent of other factors such as the state of the economy. This allows us to use these high-frequency movements as an instrumental variable in a financial market VAR, which we describe below.5.

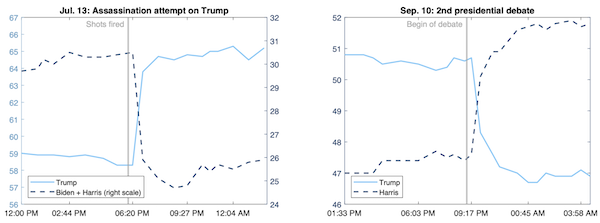

Figure 1 Betting odds around two key election-related events

Note: Implied probabilities for a Trump (light blue) and Harris/Biden (dark dashed) victory in the US presidential elections 2024 derived from prediction markets around the assassination attempt on July 13 (left panel) and the 2nd presidential debate (right panel). Values in percent. Time refers to Easter Daylight Time (EDT, Washington D.C.).

Source: ElectionBettingOdds.com, authors’ calculations.

To illustrate the approach, Figure 1 shows the evolution of betting odds around two such election-related events. The left panel depicts the implied probability of a Trump victory, next to the one for Biden or Harris, around the failed assassination attempt on Trump on 13 July. In the hours before the event, the likelihood of a Trump victory was steady at around 59%. Yet, once the failed attempt on Trump’s life – and his defiant response in its aftermath – were reported around 6:30pm EDT, the probability jumped up to roughly 65%. The odds of a Biden/Harris win dropped correspondingly. The right panel shows that Harris’ chances of winning increased by almost 4 percentage points around the second presidential debate on 10 September, in line with the perception that Harris delivered a more convincing performance.6. Notably, both events occurred when other US markets were closed (on the weekend and in the late evening, respectively), such that other US news or data releases are unlikely to explain the observed jumps.

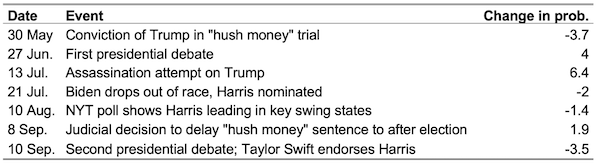

Table 1 Events used to construct the instrument

Note: The third column shows the change in Trump’s election likelihood in a 2-3 hour window around the respective event, which we use as the instrument value on these days.

Source: ElectionBettingOdds.com, authors’ calculations.

The Causal Effects of a Higher Trump Election Likelihood on Financial Markets in a Structural Financial Market Model

We estimate a financial market VAR model containing daily observations of eight variables from 1 January to 13 September 2024.7. As outlined, the first variable measures the probability that Trump will win the election, expressed in log odds. Additionally, the model contains two-year treasury yields, the (log) S&P 500, and the (log) EUR-USD exchange rate to capture important aspects of the US economy. We further add prices of assets that arguably stand to benefit from a Trump victory, as often reported in the financial press (the log share price of Trump Media & Technology Group (DJT), and the log price of Bitcoin in USD).8./sup> Finally, we include market-based inflation compensation (inflation linked swaps) in the US and the euro area over the next 24 months as a measure capturing genuine inflation expectations and associated inflation risks.

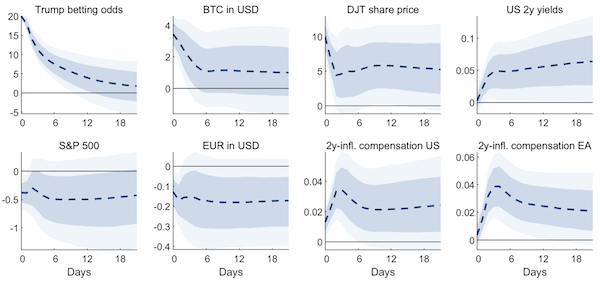

Armed with the instrument derived from high-frequency movements in betting odds, we can then identify and trace out the dynamic effects of a Trump election likelihood shock. Figure 2 shows that a 20% increase in Trump’s log odds to win the election (equivalent a five percentage point increase in the probability of a win) increases the two asset prices associated with so-called Trump trades significantly: the price of Bitcoin increases by more than 3% on impact, the DJT share price by almost 10%. We interpret these results as lending credibility to the underlying identification scheme.

An increase in the likelihood that Trump wins the presidential election also significantly affects key US financial market prices. Two-year US interest rates rise by roughly five basis points following the shock, whereas the S&P 500 tends to fall at least initially by almost half a percent. The same applies for the EUR-USD exchange rate, implying an immediate depreciation of the euro.9. Notably, both US and euro area two-year inflation swap rates rise and reach a peak response of almost four basis points.

Figure 2 Impulse responses to a Trump election likelihood shock

Note: Impulse responses in the daily financial market VAR model to an exogenous shock to the likelihood of a Trump victory in the US presidential election, normalized to increase Trump’s log odds by 20% (equivalent to a five percentage point increase in the implied probability). All values in percent(age points). Dark shaded areas denote 68%, light shaded areas 90% confidence bands.

Taken together, the impulse responses suggest that market participants associate a Trump election victory, if anything, with contractionary supply-side effects on net. Such an interpretation would be in line with standard macroeconomic theory to the extent that some of Trump’s policy proposals (imposing additional tariffs, expelling migrants) would increase price pressures but weigh on potential output in the US. If instead demand-type effects dominated, one would expect the observed rise in inflation expectations to be accompanied by an increase in broad stock market valuations. The estimated increase in two-year interest rates can be rationalised by the expectation of tighter US monetary policy as a response to rising inflationary pressures. Finally, a weaker euro is in line with expectations that Trump would raise tariffs also on European and not just on Chinese goods (Jeanne and Son 2024). This euro depreciation, alongside higher tariff-driven import prices, would transmit inflationary pressures to the euro area as well.

Footnotes

1. Under the Electoral College system, each state is allocated a certain number of electors who then elect the president. This implies that it is not the total number of nationwide votes (the popular vote) that is important. Instead, the election is in practice ultimately de-cided by voting outcomes in certain key states.

2. Polling data must be aggregated from a variety of nationwide surveys and those conducted in individual US states that vary in their importance for actual election outcomes due to the Electoral College system.

3. Albori et al. (2024) use this feature of their polling data for identification. However, as there are often many consecutive days without new polls being published, using polling data can result in measurement error and wide confidence bands.

4. For that purpose, we gather the raw data from electionbettingodds.com a website that averages betting odds from several prediction markets.

5. The instrument corresponds to the change of the implied election likelihood in a short time window around the events, and is zero on all other days. Such an instrumental variable approach mirrors one that has become standard in empirical macroeconomics to, for example, identify shocks to monetary policy (see e.g. Gertler & Karadi, 2015). Intuitively, it isolates that variation in the time series that is due to the shock of interest rather than other confounding factors. We confirm high instrument relevance, with an F-statistic of a regression of the model residuals on the instrument of > 30.

6. The Economist notes that the viewers saw Kamala Harris as the victor of the debate in instant polls.

7. As a result, the sample does not cover the recently observed divergence between individual prediction markets. We specify five lags, equivalent to one week, and use standard Bayesian Minnesota-type priors.

8. Trump has in recent months repeatedly voiced his advocacy of cryptocurrencies, reportedly claiming he would become a “crypto President” if elected. This culminated in his attendance of a Bitcoin conference in Tennessee in July and the launch of his own crypto-currency project, World Liberty, in September, for which Trump himself serves in the capacity of “Chief Crypto Advocate”. There has also been talk about plans to introduce a “strategic Bitcoin reserve”, under which the US government would buy Bitcoin as a reserve asset.

9. Both these responses – of stock prices and the EUR-USD exchange rate – are larger, more persistent and much more statistically significant when estimating the model starting in March 2024 or later.

Not to hew overly reductionist, it seems like Mr. Karau could’ve stopped at “There is large uncertainty.”

Less immigration will lead to higher wages which is the bad kind of inflation and will necessitate higher interest rates which will negatively affect asset prices.

Help Help! My hair is on fire! It’s orange and I can’t pull it out fast enough!

What’s the difference between sanctions and tarriffs (asking for a friend;)

“Less immigration will lead to higher wages which is the bad kind of inflation”

What is the good kind of inflation – higher profits?

(not that Trump has any idea what he is doing – a recession caused by tariffs or mass removal of immigrants would be bad for workers all around)

We’ve had plenty of inflation due to record profits now and no recession so why are tariffs and greater restrictions on immigration going to lead to recession?

And what do the markets think will happen if Trump wins but is not allowed to become President again? Or someone gets the bright idea to launch a nuclear weapon?

Making predictions about things with all this uncertainty seems foolish.

https://www.marketwatch.com/story/robinhood-is-joining-the-election-betting-party-by-offering-wagers-on-harris-and-trump-8bb67dbf?mod=home-page/

Robinhood is joining the election-betting party by offering wagers on Harris and Trump

The candidates are literally just race horses.

Policy in unlikely to be made by a President. Policy, at this point in history, is made by the finance oligarchs. In the case of Trump, he may be able to talk those guys into maybe investing something in the locale of the USA by trying to create incentives for investments in this country rather than in places like Europe which has its collective legs spread far apart to welcome US investors who are tempted by the relatively better educated public in many parts of Europe. Competence has not been a key part of our national culture in recent years.

As for betting on the election the disparity between the polls and what is likely to happen seems to make sense. Trump always performs better than the polls which none of us should trust though they try very hard to make it work. But in a time when favoring Trump could cost you your job people are not so likely to say they will vote for Trump.