By Lambert Strether of Corrente.

I’ve been design-adjacent for a good part of my working life. So I when I spotted CAPS LOCK in the bookstore (subtitled “HOW CAPITALISM TOOK HOLD OF GRAPHIC DESIGN, AND HOW TO ESCAPE FROM IT”), gave it the packthread test, and it passed, I picked it up. (I think the ALL CAPS cover caught, rather grabbed, my eye; attraction through repulsion, perhaps). I can recommend it to any designer or graphic artist, and indeed to anyone interested in the circulation of commodities, design’s main use case these days:

Capitalism could not exist without the coins, notes, documents, graphics, interfaces, branding, and advertisements; artefacts that have been (partly) created by graphic designers.

Ruben Pater is an an Amsterdam based Dutch designer:

[He] was trained as a graphic designer and works in journalism, activism, education and graphic design under the name Untold Stories…. His first book, The Politics of Design (2016), has been an inspirational sourcebook for design students, artists and visual communicators in many different places and contexts; Eye on Design wrote: “It’s the kind of literature that should be handed out to all students on their first days at art school, along with all the Albers, Berger, Benjamin[,] and Sontag that form the backbone of the design curriculum―an up-to-date assessment of the landscape through which all modern visual practitioners must navigate.”

Pater’s CAPS LOCK (2021) is 552 dense pages, with even denser notes, bibliography, and image credits. (Any book that has quotes from Silvia Federici and Walter Benjamin on the title page is off to a great start.) Here is the central thesis of the book, from the text pp. 7-9:

This book tries to understand how graphic design and capitalism have become caught in an infinite loop of creation and destruction. The central question of CAPS LOCK is twofold; first to historically retrace how graphic design and capitalism came to be intertwined, and secondly what strategies present themselves to unlink graphic design from capitalism, with the intended outcome of developing some kind of vision of a graphic design practice that can exist without capitalism.

And:

Design serves capitalism by devising abstract forms—infographics, money, corporate identities, branding—that hide the fact that ‘the economy’ is a collection of social cooperative relations between people [see under “commodity fetishism”]. That’s why, as a critique of design itself, this book doesn’t follow the method of design theory, which usually centres designed objects. Precisely because capitalism manifests itself not only in the appearance of posters, books, or websites, but more in how they are produced, where they are they published, and how they are sold. The first part explains how the work of graphic designers bolsters capitalism and economic relations…. The second part explores how designers themselves are economic actors too.

From one favorable review (there are many), the structure of the book. Design and Culture:

In Caps Lock, Ruben Pater provides a comprehensive and chronological history of the long and complicated entanglement between graphic design and capitalism, which he defines as ‘an economic system that is founded on three basic principles: everything should be privately owned, all production is for the market, and people work for a wage'[1]. He accomplishes this by meticulously examining twelve evolving roles that designers have played throughout history, beginning with ancient Mesopotamian scribes who kept financial records and concluding with interviews with contemporary design activists and activist collectives worldwide attempting to work ethically within the capitalist system. He covers the designer as engineer, brander, salesperson, worker, entrepreneur, amateur, educator, hacker, futurist, and philanthropist. While the list of roles may seem overwhelming, it accurately encompasses the many hats designers wear throughout their career, if not in one day.

In this hasty review, I’m going to present just enough material for you to decide whether to acquire the book for yourself. First, I’ll give two examples of the the insightful true facts about “abstract forms” scattered liberally throughout the book: banknotes and international standards. Then I’ll give two examples of Pater’s approach to social relations: the precariat, and mutual aid. In conclusion, I’ll return to the issue of severing the relation between graphic design and capitalism. (For each of these four examples, I’ll present screen shots of relevant pages; I’m afraid my lack of a copy stand is all too evident, and I apologize for the clumsiness of the highlighting.)

Banknotes

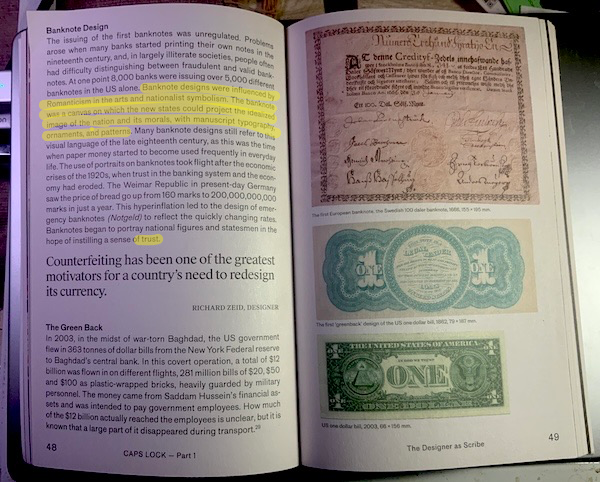

Here is Pater on banknotes:

The insight here — so obvious it’s hard to see — is that the banknote is designed, an abstract form, trust being the essential desideratum in the designer’s brief. I’m forcibly reminded of Terry Pratchett’s Making Money, where newly minted central banker Moist von Lipwig tests his invention of the banknote in Ankh-Morpork, Pratchett’s exercise in world-building:

Where do you test bankable idea? Not in a bank, that was certain. You needed to test it where people paid far more attention to money, and juggled their finances in a world of constant risk where a split-second decision meant the difference between triumphant profit or ignominious loss. Generically it was known as the real world, but one of its proprietary names was Tenth Egg Street…. Tenth Egg Street was a street of small traders, who sold small things in small quantities for small sums on small profits. In a street like that, you had to be small-minded. It wasn’t the place for big ideas. You had to look at the detail. These were men who saw far more farthings than dollars.

After a discussion of monetary theory that would make Stephanie Kelton scream and run, the banknotes pass:

‘So you think these could catch on?’ he said, during a lull.

The consensus was, yes, they could, but they should look ‘fancier’, in the words of Natty Poleforth: ‘You know, with more fancy lettering and similar.’

Design!

International Standards

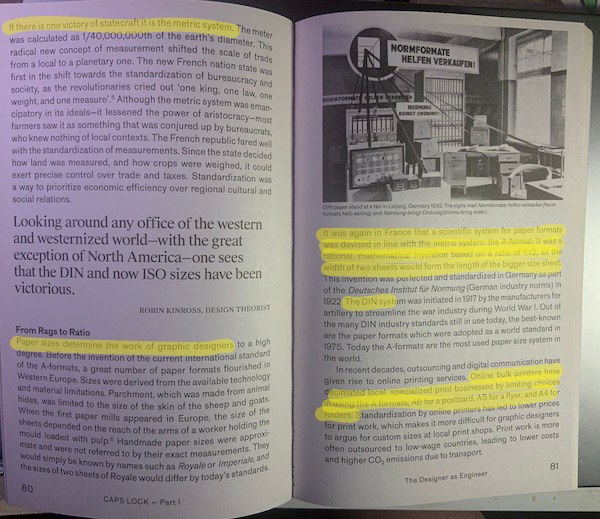

As readers know, I stan for international standards (“Royale with Cheese”), so here again is an insight so taken-for-granted it’s hard to see:

(I love “if there is one victory for statecraft it is the metric system,” and commend it to my anarchist friends). And that the French invention of the A-format for paper — a fundamental constraint for designers today — was optimized by German artillery manufacturers’s in World War I… Well, it’s a wonderful world.

The Precariat

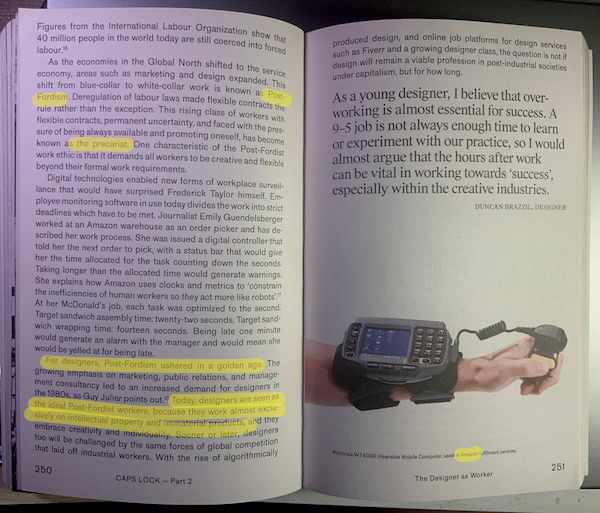

To me, “freelancer” and “designer” are almost synonymous, and have been for decades, very much pre-Uber:

But as far as post-Fordism, wait until symbol manipulation is automated…

Mutual Aid

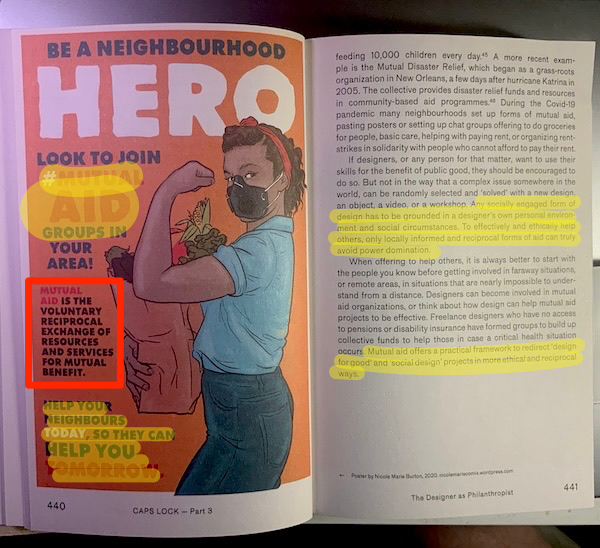

Pater practices what he preaches. In an interview with Print magazine:

[PATER:] Now I only work with local printers and producers, I don’t fly to conferences or lectures, I focus on projects in my neighborhood, in my workshops I focus on local issues rather than “global” ones, and if I work with people I pay them well (the proceeds of the book are shared with all image makers that have contributed). Instead of pushing my own authorship, I prefer giving the stage to young makers so they have a chance to make some money and show their talents.

My latest project is setting up a collective activist media/printing workshop/publishing house/meeting space in Amsterdam, together with extinction rebellion and the anarchist union. The extreme rent prices in Amsterdam make it almost impossible to have permanent spaces devoted to noncommercial purposes, and such a cooperatively organized space would really give a boost to young activist designers and artists looking for places to work. With our own means of production in-house we wouldn’t rely on bulk printers that use toxic inks. It has not been easy to organize a space like that with that many people, but it has already led me to get to know more like-minded people and forge bonds.

Absent The Jackpot, when I would expect most of what we consider “global” to collapse, I don’t know if this approach scales. But it’s certainly worth a try. From Eye on Design:

Throughout his book, Pater grapples with a popular meme that declares “there is no ethical design under capitalism.” In its favor, he lays bare how efforts to design ethically are qualified by this coercive social system that good deeds never quite fix. Even political protest, he shows, can be tolerated by capital or even turned into “causewashing” by brands eager to strike an activist pose. But if the above sounds a bit gloomy, Pater is remarkably optimistic when it comes to opportunities for resistance. Each of CAPS LOCK’s chapters ends with hopeful advice and speculation on ways design can proceed more ethically and less immediately under capital’s control. The wealth of ideas here are inspired by politically engaged collectives like Cooperativa de Diseño in Buenos Aires and The Public in Toronto, which feature alongside four others in extended interviews that make up the book’s last section. Together, they speak to the potential of less hierarchical working relationships, freer access to the tools and products of design, and deeper connections with communities in struggle.

Conclusion

If capitalism were to end, would there even be a need for design? From the American Institute for Graphic Arts:

In fact, the book’s insights add up to suggest that it might be easier to imagine the end of capitalism without design. In a world built not around wages and profits, but around freely associated individuals fulfilling social needs, what place would there be for fine-tuning images for countless, nearly identical products competing for market share?

Pater, however, disagrees. From an interview with Print magazine:

[PATER:] In CAPS LOCK, I don’t present the link between graphic design and capitalism as exclusive. I think we can establish that there is a lot more to graphic design than being a tool of capitalism. Some of the most iconic (Western) design examples from the 1970s–1980s were made for noncommercial purposes—public transport, government services, education, etc. Emory Douglas is a graphic designer I admire who certainly wasn’t a tool of capitalism. The Russian Constructivist designers were anti-capitalist and influential to early modernist graphic design in Europe. There are plenty of examples of graphic design before capitalism existed; whether it’s the Trajan column, Garamond’s types, maps by the Aztecs, or African alphabets. I mention in the book a map found in Spain from 17,000 years ago, etched on a stone. It suffices to say that graphic design has its uses beyond serving capitalism, has existed before, and will exist as long as people need visual communication.

“Exist,” and hopefully be created, first-hand, by humans.

NOTES

[1] It’s hard to get the definition of capitalism on a postcard, so I don’t wish to pick a quarrel here, but the origin of profit (for example) is missing in this formulation. Beginning with the four “ex’s” — extraction, extortion, exploitation, and expropriation — as called out in the front matter to the new translation of Capital Volume 1 by Reiter et al. (summarized by KLG here) strikes me as a better jumping off point.

APPENDIX 1: A Lecture on Caps Lock from Ruben Pater

APPENDIX 2: Hillary vs. MAGA

In the interview with Print, Pater comments:

I often think about the Trump hat design versus the identity Pentagram [, the design firm, made] for Hillary Clinton’s campaign during the U.S. elections [in 2016]. Effective graphic design is not about making something look more beautiful or professional, it is about understanding who you are speaking to, and to show you are interested in what they want without trying to con them. That is exactly why I think graphic designers and journalists are needed.

Here is Clinton’s logo:

And here is a MAGA hat. CAPS LOCK on:

Interestingly — and Pater does not mention this — Clinton’s logo is all about a person: “H” for “Hillary” (with, weirdly, or possibly not weirdly, an embedded arrow pointing right). “MAGA”, on the other hand, is all about policy; or rather, a set of implied policies that will “MAKE AMERICA GREAT AGAIN.” And which was more effective? And which was the con job?

Clinton’s logo: you have to look at it for a few seconds before you see the H, so I’m not so sure the logo is about a person. “I like Ike” was about a person and it was quite successful, being connected to a person who was indeed liked.

What stands out to me about the Clinton logo is the Mondrianized corporate logo style, which might convey a specific brand of universal harmony and order through abstraction and reduction. This would appeal to a very small portion of the general population.

Clinton’s logo strikes me as the reverse of the FedEx logo. For Clinton the arrow is right there, and you have to figure out what else is going on. For FedEx every thing else is right there, and you have to dig out the arrow.

Yes, the Hillary logo is all design (needs interpretation) while the MAGA logo is a wearable statement (text needing no interpretation).

Note that the arrow points to the right which suggests a lack of ” understanding who you are speaking to, and to show you are interested in what they want without trying to con them.” We know how deplorably that worked out for HRC®.

Darn. Another book to think about reading…

I was disinclined to support Hillary Clinton, which does NOT mean I defaulted to the current President-elect, but the red arrow pointing DEAD RIGHT was always off-putting to me. Aside from the political suggestions, it reminded me of a (failed) biotech startup (that sank without a trace except for the ill will left behind) I was involved with in the late-1980s. The primary motif for their logo was an Erlenmeyer flask, laboratory glassware introduced into chemistry labs in 1860 by Emil Erlenmeyer. A molecular biology laboratory cannot do without them, but when I mentioned to a founder that this wasn’t exactly “modern,” he replied that he had not thought of that. His artist son was the designer. I always wondered what he had been paid, because these brain geniuses bought new Herman Miller furniture for their offices and lab in rented space they renovated at great expense when the university would have given them “incubator space” in a former textile mill for FREE.

Yes! The arrow pointing to the right suggests a lack of ” understanding who you are speaking to, and to show you are interested in what they want without trying to con them.” We know how deplorably that worked out for HRC®.

Much is made of the arrow pointing right in the Hilary logo, but here I have to point out that, given the Western reading direction of left to right, a rightward arrow is typically understood to indicate forward / future motion and has little to do with the political right. The logo as a whole, however, is a collection of bland geometry and would look just as at home pointing to an airport toilet nook as it did on a campaign flyer.

Grateful for this! Am going to ask Santa for it. It looks full of “heady goodness”!

I realize that both you and Mr Pater have more experience and knowledge than I do, but imo the Hillary logo is unsuccessful because it does exactly what her entire campaign did. It says nothing. It wasn’t clearly about her. If you didn’t see it attached to an ad or a mailing you would never know who it was referring to. it didn’t cheekily tell policy. It was as much or more a play on the Fed Ex logo as anything political. It was expensive and upscale and vacuous. It was just supposed to be embraced because.

Trump’s hat logo wasn’t elegant but it was clear. He might not have plastered his name on it like his usual branding, but he and his people had read the room well enough to find a sales pitch that resonated. And they used it with few flourishes.

I think of it this way. Only one campaign was aware that this was a sales campaign to encourage voters to buy/vote for their product/candidate and acted accordingly.

> It says nothing. It wasn’t clearly about her. If you didn’t see it attached to an ad or a mailing you would never know who it was referring to.

Interesting point. This is a very PMC way of telegraphing belonging or knowing. In a sense, it was for those in the know, those who get it – right? Her single word slogan for her campaign was “Forward”, IIRC, and the logo design was ultimately as vapid as the slogan itself.

>He might not have plastered his name on it like his usual branding, but he and his people had read the room well enough to find a sales pitch that resonated.

Another great observation. It is his greatest gift. Trump reads the room and cuts through the bullshit, whereas team Dem tries to finesse around the bullshit by presenting itself as the class of superior moral authority – see lawfare, and “the prosecutor versus the felon” (the felon won!). Does anyone remember what Hilary’s response to “Make America Great Again” was? It was “America Is Already Great” – yep, the tone deafness of not being able to read the room.

I think that design is also going to have to incorporate the subject of fonts in it. Minor example. Look at that that MAGA cap and note that all of the letters are in capitals. That was a deliberate design choice that making a statement. Further to this point, here is a trailer from the 2007 doco about the font Helvetica-

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wkoX0pEwSCw (1:35 mins)

So graphic design should also mention fonts if it does not already.

Great review: I wonder though whether Pater also delves into design in contexts such as Mao’s China? What happens when social relations and design are more ambivalent to each other, in a sense that design is practically employed by the state propaganda machinery for its legitimation and then reproduced in a grammar by small scale designers/social actors who “believe” in the revolution or perhaps find making design “fun” as a social activity?

Or on the other hand, a big design&invention success story of the GDR socialist market: jenaer glass, or Superfest, the unbreakable glass. The East Germany wanted to export it, but it wasn’t bought by the “West” since the sales would soon stop if glass didn’t break…

Beautiful topic and recommendation.

Oooooh! Thanks for this, Lambert! I will get this book! It should serve as an interesting bookend to a copy of “The Design Of Dissent” (via commarts.com) which I picked up years ago.

Much of the discussion here is of design used in the direct service of capitalism, that is, advertising and brochure design.

For most of my career, I was a book editor. Graphic design in books is less meretricious. I recall attending Edward Tufte’s weekend program. At one point he held up his own copy (an original) of Galileo’s Starry Messenger. Galileo, notoriously, had overseen typesetting and design. The book is timeless. It is a testament to Galileo’s genius — as a popularizer.

Bodoni also was a popularizer and help to introduce elements like better typefaces and standardized trim sizes. So I am a tad skeptical, at least as someone whose life centers on books.

On the other hand, I have always been leery of the vogue for collecting French advertising posters. Sure, many of them are remarkably well designed. But does one truly want a showy advertisement for rubber tires in the living room? The concept, advertising = art, somehow, who knows why?, is off-putting.

Another person worth looking at with regard to anticapitalist design is Molly Crabapple.

Finally, pace footnote one, I think this a good way of thinking of capitalism, and it also observes the Rule of Three: “entanglement between graphic design and capitalism, which he defines as ‘an economic system that is founded on three basic principles: everything should be privately owned, all production is for the market, and people work for a wage’”

Finally, finally, the graphic appendix: Surely we must contemplate the irony of people wandering around in baseball caps (which is what such caps used to be called) when they couldn’t waddle around the bases, even if they had hit the ball out of the park and had time to do so. So: and this may be capitalism at its highest point — the object loses its original function and becomes a monetized simulacrum. Make America Less Chunky Again!

What did you think of Tufte?

.Tom

Lots of respect for Tufte. He’s just darn cranky enough about the chart-junk out there to get his point across. And, as in so many areas of life, it doesn’t take all that much work to get truly better results.

I have done much work on books in statistics, chemistry, biology, U.S. history, and government. You have to be cranky about how data are displayed — especially when the other editors and the author think that one should “pretty up” the displays of data. (And the photos, but that’s another story.)

Tufte showing the Starry Messenger was a revelation…

Thanks, Lambert. Not long ago, in the UK and possibly elsewhere, we referred to graphic designers as commercial artists. You could go to college to study commercial art. So on the face of it it seems odd to talk about separating commercial art from its service to capital. But commerce and capitalism aren’t necessarily inextricable, commerce can exist without capital accumulation and social power being given to those controlling the most capital.

Earlier this year I reviewed the book The Great Psychic Outdoors – Adventures in Low Fidelity by Enrico Monacelli. It is unconvincing and doesn’t even state its thesis very clearly but it’s about how pop music can separate from service to capitalism. Pop music is commercial music so for the artist it presents a similarly conundrum. But we anarchists aren’t opposed to commerce per se and therein lies some hope.

You could have done with a Graphic Designer to do your text selection on the photos, Lambert. All that yellow highlighting actually makes the selected text much harder to read!

Better would have been to draw a ‘box’ round the relevant sections.

What a wonderful book ! Thanks for tip off. Kind of reminds me of McLuhan in “The Mechanical Bride” and/or “The Gutenberg Galaxy”. -cheers, a.v.

I’m the late (and slow, reading) introvert and I approve of this post. Unfortunately my library does not have a copy. And I already have too many books for my house so anything I can’t hold to my chest has to remain unread for now. I will check back with the library though, this looks like a great book. There is also interlibrary loan, but if it’s a new book it might take awhile for it to show up.

I have no design chops whatsoever but have worked with some very clever ones.