By Lambert Strether of Corrente.

Readers who have been following our HICPAC coverage (here, here, here, here, and here) know that “HICPAC” stands for Healthcare Infection Control and Prevention Advisory Committee. CDC’s Daniel Jernigan and John Howard describe HICPAC’s purpose as follows:

HICPAC is a federal advisory committee appointed to provide advice and guidance to the Department of Health and Human Services and CDC regarding the practice of infection control in clinical settings. CDC plans for updates to [the CDC guideline on isolation precautions] to be accomplished in stages over a period of several years. The first step is to complete a framework document that will be part one of the updated Guideline to Prevent Transmission of Pathogens in Healthcare Settings (“Guidance”). The framework provides the scientific foundations that will be used when prevention recommendations are developed for specific pathogens and clinical situations that will be subsequently developed through HICPAC as part two of the guideline.

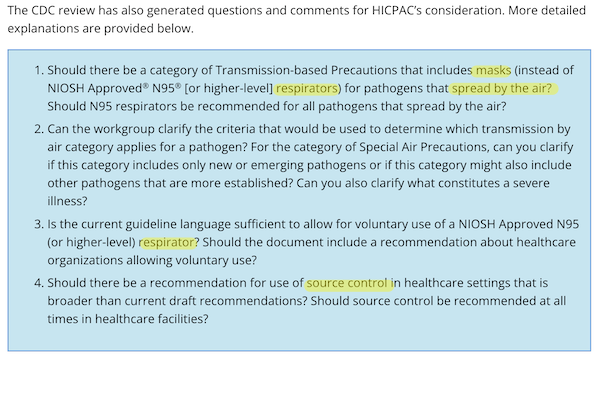

To set the scene for the bureaucratic knifework to come: The draft “Guidance” of the last HICPAC meeting, which proposed to weaken patient protections from Covid, raised such a furor (“murderous abomination“) that its masters at CDC felt that it needed to be fixed. Jernigan and Howard then attempted to get HICPAC back on track, in January, by writing a letter to them that posed four questions for HICPAC to answer as it redrafted the Guidance. The deliverables presented, in November, at the meeting I am about to describe, enabled HICPAC to answer CDC’s four questions.

In this post, as a preliminary, I will first review HICPAC’s compliance at this meeting with issues raised by the World Health Network (WHN) with the Inspector General of Health and Human Services, the parent agency of CDC. I will then present CDC’s four questions, followed by HICPAC’s definition of masks. Next, I will look at two deliverables, Infection Control in Healthcare Personnel Workgroup (“Infection Control”) and Isolation Precautions Guideline Workgroup (“Isolation Precautions”), that HICPAC used to answer CDC’s four questions. After looking at HICPAC’s answers to those questions, I will conclude. (The meeting ran over two days, and unfortunately I did not have time to listen to the video recordings for November 14 and 15, 9 hours 44 minutes and 4 hours 31 minutes respectively. Public comments were held November 15, at the end of the meeting.) Here are two articles (Judy Stone in Forbes; Infection Control Today) that handle this HICPAC meeting at a higher level.

Compliance Issues at HICPAC

For a detailed discussion of World Health Network’s Complaint, see NC here.

(1) Quorum. Still non-compliant per WHN’s complaint. HICPAC is legally mandated to have 14 members. However, the HICPAC roster shows only 11. I don’t see how a committee that doesn’t meet its basic legal requirements for membership can call a meeting in the first place, let alone declare it has a quorum[1].

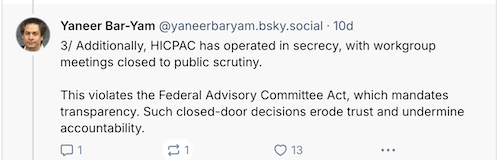

(2) Secrecy. Yaneer Bar-Yam of World Health Network posted:

HICPAC’s workgroups produced Infection Control and Isolation Precautions for the full committee to vote on, so this is a big deal.

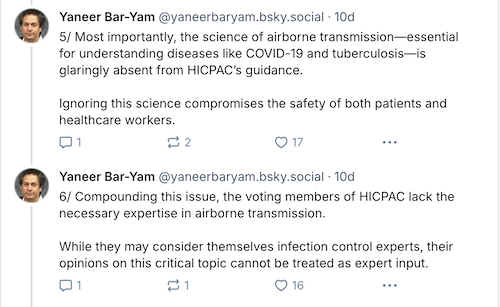

(3) Committee Composition. Yaneer Bar-Yam of World Health Network once more:

On committee composition, Jernigan and Howard wrote:

CDC is working to expand the scope of technical backgrounds of participants on the HICPAC Isolation Guideline Workgroup and eventually among the committee members through established processes in accordance with the Federal Advisory Committee Act (FACA) regulations and guidance. The expanded workgroup and the HICPAC with the newly appointed members will review and discuss these additional considerations and guideline at the next HICPAC meeting, which is open to the public.

HICPAC has in fact expanded workgroups to include specialists in airborne transmission. But these specialists are not full members of the committee, and therefore have no voting rights. So are we really going to complete the Guidance without giving scientists or engineers a vote?

(4) Conflict of Interest. Summarizing WHN’s complaint, I wrote (and forgive the length and breadth of the elephant in the room):

WHN has now gone for what is really the jugular: Following the money.

A. Financial Relationships. WHN writes:

An important principle of FACA is that employees of the agency that is being advised (in this case, the CDC) are not allowed to be members of the committee due to the inherent nature of financial relationships that may preclude independence. While funding is not strictly forbidden, it is apparent that conflict of interest should be avoided.

A financial relationship between the institution and individual members such as that which currently exists between CDC and virtually all of the members of the HICPAC committee seriously risks comprising the independence of their judgment. This is the case not merely because funding links may influence particular decisions, but also because the relationships created by such funding may well incentivize the committee to advance or reject decisions of certain types, such as refusing to recognize the full impact of an airborne pathogen on hospital-based infection and the practical steps that must be taken to address this pathogen.

To put it crudely, if CDC’s handwashing desk writes your HICPAC check, you will be unlikely to give airborne transmission the attention it deserves.

B. Competition for Funding with Rival Siloes. WHN writes:

Furthermore, members of HICPAC, recognized for their expertise in areas such as bloodstream infections, sepsis, sharps injuries, hand hygiene, fomite transmission, sterilization and disinfection, antimicrobial resistance, and Ebola, are funded specifically for their work in these fields and would not be funded for airborne transmission prevention. This creates a potential conflict of interest which may interfere with a decision to shift the focus of infection prevention to airborne diseases, which is required to deal effectively with the hospital-based transmission of COVID-19. Such a shift could threaten the funding that supports their salaries, research, staff, and programs, as well as their positions of authority in infection prevention and control [IPC], and that of their colleagues. This inherent tension is compounded by similar conflicts of interests among CDC officials responsible for nominating HICPAC members and setting the committee’s agenda, including the current and former HICPAC Federal Officers and the director of NCEZID.

I don’t know anybody who has an issue with threatening IPC. Do you? (And if these two sections make HICPAC and CDC seem like a snakepit of self-dealing, well, it looks like that’s what it is. It would also be interesting to know if the CDC Foundation is hooked into this “inherent tension” at all.)

C. Perverse Incentives in Fee-for-Service Systems from Hospital-Acquired Infections. WHN writes:

HICPAC’s Charter mandates providing guidance on “prevention, and control of healthcare-associated infections” Therefore, committee members that are compensated for encouraging spread of infection (or compensated for being knowingly or willfully ignorant of the science of infection control in a healthcare setting), are in conflict of interest with HICPAC’s objective.

More specifically, it is well established that direct payment systems can lead to perverse incentives against the prevention of hospital-acquired infections (HAIs). In fee-for-service payment models, hospitals are reimbursed for services provided, including the treatment of HAIs. In such a system, hospitals can generate more revenue by providing additional care to treat these infections, rather than by preventing them in the first place. Many members of HICPAC are from hospital management, and as such, have direct financial interests that conflict with the prevention of HAIs. This conflict of interest, long recognized in the context of other HAIs, must now also be addressed for COVID-19 and other airborne diseases.

At the start of the meeting, the roll is called as the quorum is taken. The Committee members answer with their names and Conflicts of Interest. It’s amusing to hear so many of them say “no conflict.” Same as it ever was. Nothing has changed.

CDC’s Four Questions

From Jernigan and Howard’s letter, here they are:

In what follows, I’m going to focus only on masks (and respirators), because universal use of respirators in hospital settings is my hobbyhorse policy goal.

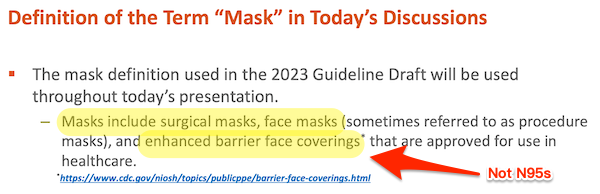

HICPAC’s Definition of “Mask”

From page 29 of Isolation Precautions:

(A BFC is a “Barrier Face Covering.” They are less effective than N95s). In other words, in the HICPAC context, respirators are not one type of mask, but entirely different. From a usage perspective, this is unfortunate: Mask is usefully both a noun and a verb, so people mask, are masked, practice masking; but people do not respirator, are not respiratored, do not practice respiratoring, so to a dull normal[2], respirators may be deemed a type of mask. Further, it seems weird to mention BFCs (definitely “Today I Learned” territory) and not respirators. In fact, doesn’t it seem odd that there’s no parallel slide entitled “Definition of the Term ‘Respirator’ in Today’s Discussion”? For example, an N95 is not a KN95 is not a KN94. And is an elastomeric a respirator? Inquiring minds want to know! In fact, it’s almost as if the authors of Isolation Precautions really didn’t want to talk about respirators at all….

Infection Control in Healthcare Personnel Workgroup

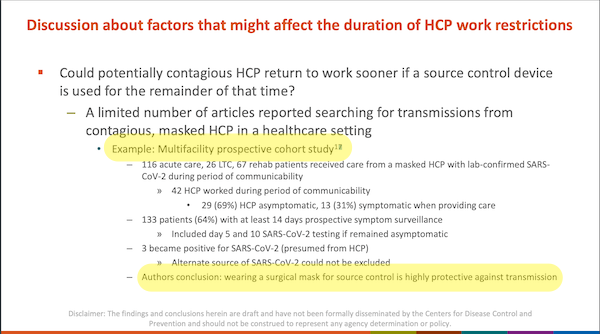

For Infection Control, I’m going to look at just one footnote: footnote 17 on page 19:

Here is the note itself, on page 59:

![]()

From page 19, helpfully highlighted at the bottom:

Authors [sic] conclusion: wearing a surgical mask for source control is highly protective against transmission

From the actual article, “Risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission from universally masked healthcare workers to patients or residents: A prospective cohort study,” in the conclusion:

Our study provides evidence that universal masking, embedded with other infection control practices, is associated with low risk of transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from healthcare workers to patients and residents.

In other words, in their version of the authors’ conclusion, the authors of Infection Control, workgroup chair Connie Steed and David Kuhar left out all the confounders (helpfully underlined).

Isolation Precautions Guideline Workgroup

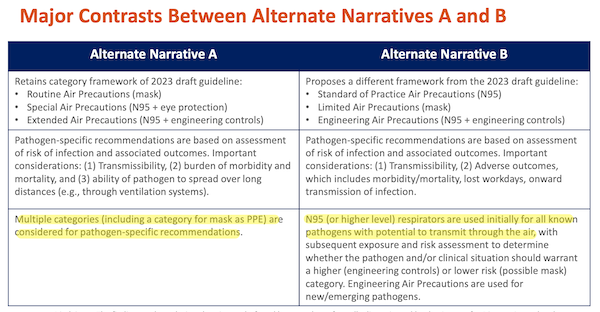

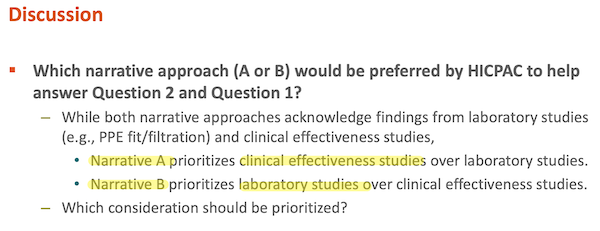

This is the knifework part. Evidently — although since the Workgrup deliberations are secret, violating FACA, as WHN points out above, we can’t be sure — this workgroup was organized along Team A/Team B lines, where Team A is hospital infection control administrators, and Team B is scientists and engineers familiar with aerosol tranmission. For the Guidance, each team produced “narratives.” From Isolation Precautions, page 69:

And the narratives of each team were supported by different classes of evidence: “clinical” (no doubt hospital administrators) and “laboratory” (no doubt scientists and engineers, though heaven knows there are fine studies done on aerosol tranmission, too). From Isolation Precautions, page 70:

I’ll just leave this here, for now, but we’ll get back to the knifework in the Conclusion.

HICPAC Answers CDC’s Four Questions

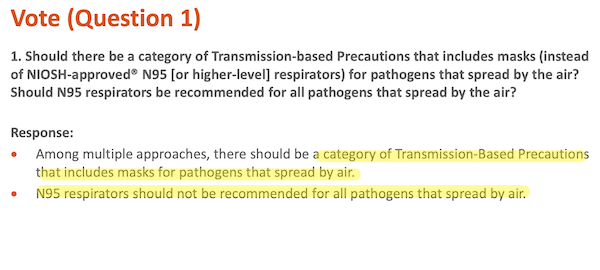

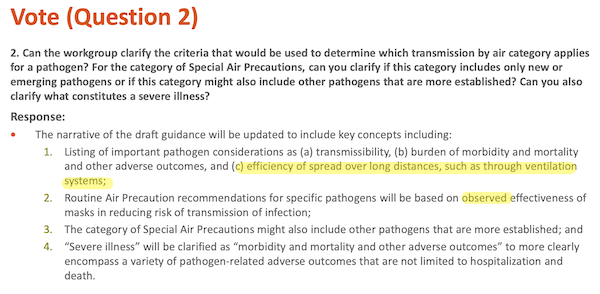

Here now are HICPAC’s answers. As you can see, the results are a rout for Narrative B (respirators). Baggy Blues über alles! Let’s take the questions one by one”

On the bright side, finally HICPAC admits airborne transmission. Sadly, “N95 respirators should not be recommended for all pathogens that spread by air.” (And think about that for a moment. What happens if there are multiple airborne pathogens in a given hospital simultaneously? Should the most protective (respirator) or least (mask) be used? Will hospital administrators be issuing memos on mask v. respirator use on a daily for weekly basis? (Keeps ’em busy, I supppse.) Why not go for the simplest solution that’s effective in all cases?

“Efficiency of spread over long distances, such as through ventilation systems”? I can’t believe Team B allowed that. The Japanese 3C’s concept applies to a hospital room or war just as much as a restaurant: closed spaces, crowded places, and close-contact. Further, aersols move like smoke and gradually fill rooms. In neither case is “long distance” an appropriate model.

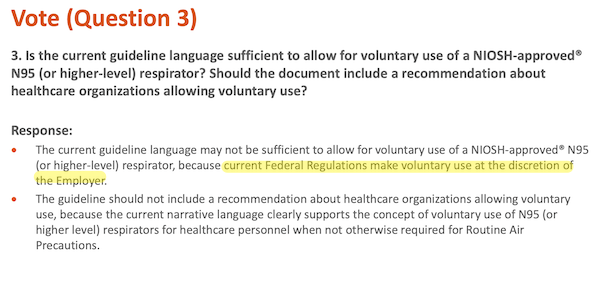

The least HICPAC could do is ask for the regulation to be changed.

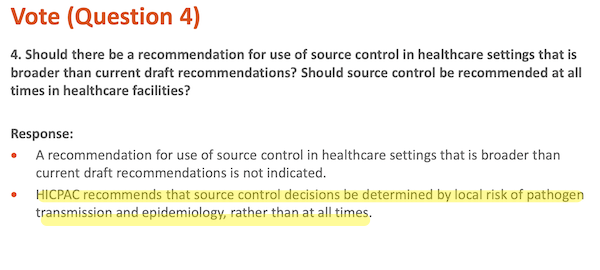

“Determined by local risk of pathogen transmission and epidemiology, rather than at all times” has some problems. First, to assess the risk, you need to test, and for all airborne pathogens, but HICPAC isn’t recommending that. Second, assume that HICPAC recommends periodic testing for some pathogens. That implies that some will be infected before the testing flags risk (exactly the mistake CDC made with its green maps, before it destroyed testing entirely).

Conclusion

Any dull normal who isn’t a member of a high-powered Federal Advisory Committee knows that “Baggy Blues” are gappy; if you put one on, you can feel the air coming in and out through the sides (and since #CovidIsAirborne — or, heaven forfend, H5N1 — Covid is coming in and out too)[3]. N95s with proper headstraps are less gappy by construction; and with fit-testing, not gappy at all. Further, N95s are made from non-woven fabric with a static electrical charge; air gets in and out, but the charge traps particles like Covid viruses. Baggy Blues are better than cloth masks, but they don’t have the static charge, so again, N95s are better by construction. Baggy blues are simply not as good as N95s, let alone elastotmerics, meaning that fewer people will get sick and die with N95s than with Baggy Blues, which you’d think would matter to hospitals, but I guess not. But HICPAC vociferously maintains that they are as good.

How then is it possible for smart people to be so stupid? Leaving aside corruption conflict of interest, the very simplest explanation is to look at the bureaucratic knifework (I told you I’d come around to it again). You will recall that Isolation Precautions said there were two kinds of evidence: Clinical (Team A, masks) and Laboratory (Team B, respirators). So where are all the people favoring Laboratory Evidence? That’s right. In the Workgroups, with no vote. And who are the people favoring Clinical Evidence? Yes, clinicians. On the Committee, with a vote. Given the committee composition, the outcome — masks > respirators — is not hard to predict, especially given that the clinical evidence for masking was cherry-picked anyhow. HICPAC rigged the committee. The fix was in.

NOTES

[1] “What they mean by ‘having a quorum’ has not been clarified but the usual definition of having a quorum is having the legally required number which they don’t have” (Yaneer Bar-Yam, via email.) I did a little digging. As best I can determine–

Starting with the video for November 14, we see the unidentified convenor (likely Sydnee Byrd, a contracted CDC program analyst) call the roll. All eleven members from the HICPAC roster respond “present.” The convenor then calls on the ex officio members. Finally, at 00:03:41, the convenor states: “We have made meeting and voting quorum.” The process seems a little murky. First, typically the Chair calls a meeting to order, and then requests that a Secretary (or some other registrar) perform the roll call. In this case, the meeting is never called to order, and a non-member (probably Byrd, the Federal contractor) calls the roll. That seems odd. Second, CDC apparently believes (see the August meeting recap) that a quorum can be “reached by having 10 HICPAC members and 2 ex officio members in attendance.” That is twelve, not fourteen (or eleven). This is odd, since the typical quorum for a commmittee of fourteen is calculated at eight, not twelve. That said, typically ex officio members can vote, so it makes sense to include them in a quorum. It seems, however, that HICPAC has achieved the positively surreal position of being a Committee that should not be able to function at all (eleven members on the roster, not fourteen) nevertheless being able to reach a quorum (and given everything else CDC has done in this pandemic, “surreal” is by no means out-of-band for them). Fourth, why does CDC have two flavors of quorum, “meeting” and “voting,” if indeed ex officio members can vote? Finally, a Committee can meet without a quorum, but it cannot transact business, and cannot present information or committee reports. Note that every item on the agenda is informational, and Infection Control and Isolation Precautions are workgroup reports to the Committee. At this point, the HICPAC bylaws — if any — would be really useful. Perhaps some kind soul will throw a copy over the transom.

[2] From Cnet: “All face masks aren’t equal. There’s a wide spectrum of protection available, from medical-grade respirators to handmade cloth face coverings.”

[3] Feeling air come out of the gaps in a Baggy Blue is a fine example of what Isolation Precautions calls “laboratory evidence.”

Alas, I am unable at the moment to cite the study, it was linked and discussed on This Week in Virology some months ago, that concluded that bandanas worn as masks were about equally protective against airborne pathogens than are surgical masks. The latter are primarily effective in preventing health care providers from drooling on their patients.

Eureka!: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/ebiom/article/PIIS2352-3964(24)00192-0/fulltext

This study is discussed at minute 10:02 on TWIV’s Clinical Update with Dr. Daniel Griffin on June 7, 2024.

Lambert, thank you for this post and for your dedication to this matter, I’m keeping up with this and another related (for my covid concerns here) post by Yves regarding neglecting health care possibly affecting the election in Black and Brown communities

Patient readers, I expanded footnote [1] on the issue of HICPAC quorums. If we have any Roberts Rules mavens in the readership, perhaps they would care to comment.

Sigh. They had a conclusion they wanted to get to and they got there. “You people” looking in just meant they had to try to dress it up a bit more, to make it seem “official”. Is there any legal recourse?

Legal? I’m not smart enough or educated enough to know. If there even might be, I hope somebody wages Guerilla Lawfare against all the right targets.

There might well be some sort of partial recourse on the cultural side. The infection-cautious Covid Realist Community can try recruiting new members and spreading reality-based counter-infection methods to all who seem prepared to learn’em live’em love’em.

Barry Hunt has a nice succinct thread on this whole thing……

https://threadreaderapp.com/thread/1861441382465814789.html

10 highly conflicted people deciding for 387 million………