Lambert here: “There is no such thing as civil society.” –Maggie Thatcher (apocryphal)

By Samuel Bowles, Research Professor and Director of the Behavioral Sciences Program at Santa Fe Institute, Wendy Carlin, Scientific Council at Paris School of Economics (PSE), External Professor at Santa Fe Institute, Professor of Economics at University College London, and Sahana Subramanyam, a third-year economics PhD student at Stanford. Her research interests are at the intersection of gender, development and behavioral economics. Originally published at VoxEU.

Commentary on the 2024 US elections included the Democratic Party’s failure to connect with issues of community, place, family, religion, and identity [and class–lambert]. This column presents evidence from research papers published in the top economics journals since 1900 showing that half a century ago, economists took a little noticed turn towards precisely these topics. The authors document this shift and show that it was associated with novel empirical methods including experiments, large data sets, and an increasing focus on social norms and strategic interactions – including the exercise of power.

A substantial shift in the focus of economic research over the last half century has for the most part gone unnamed and unnoticed. This is the turn towards what we call civil society, including firms as organisations, families, neighbourhood communities, NGOs, trade unions, social movements, identity groups, and other face-to-face settings. Although the term will be unfamiliar to many economists, it dates back to Adam Smith and the Scottish Enlightenment, and has been variously applied in the other social sciences and philosophy (Cohen and Arato 1994, Edwards 2011, Ferguson 1767, Smith 1976 [1759]).

Economic interactions in civil society, as we use the term here, have in common that relationships are personal and enduring. As a result, identity and other-regarding preferences (for better or worse) are important motives. In civil society, the primary mechanisms guiding economic interactions are neither governmental regulations nor complete contracts and market-determined prices, but are instead hierarchies of private authority and power, social norms, group identity (including out-group hostility), and reputation. (We explain the concept of civil society at greater length in Bowles and Carlin 2025.)

The turn towards civil society in economics that we document (Bowles et al. 2025) is consistent with two propositions. The first is that much of what we think of as the economy consists of non-market interactions and exchanges under incomplete contracts within the firm as well as in labour, credit, residential housing, and other markets. Second, in these and in other settings, ethical and other-regarding preferences have an important place along with self-interest in explaining behaviour and supporting mutually beneficial exchanges (Arrow 1971).

The proliferation of civil society themes that we document in the research corpus was enabled by conceptual innovations (including the information revolution and game theory) and empirical methods (including experiments, other advances in causal identification, and the use of large data sets). The shift in focus has been reflected in Nobel awards to Myrdal and Hayek (in 1974), Simon (1978), Coase (1991), Nash (1994), Sen (1998), Akerlof and Stiglitz (2001), Kahneman and Smith (2002), Schelling (2005), Ostrom and Williamson (2009), Hart (2016), Thaler (2017), Goldin (2023), and a few weeks ago, Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson (2024).

Markets, States, and Civil Society: Topic Modelling Themes in Economic Research

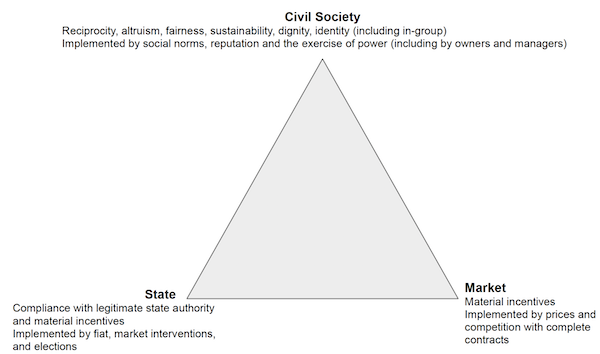

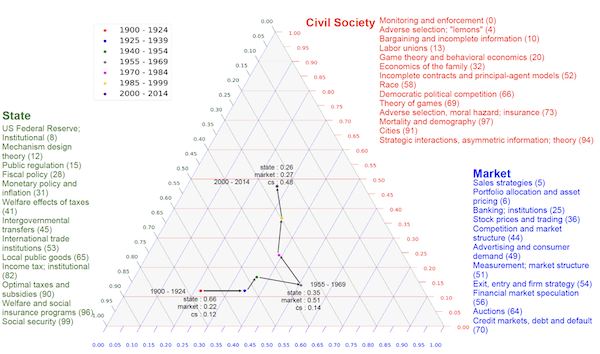

We represent civil society along with states and markets as distinct and ideally complementary structures of societal governance. In Figure 1, we treat the pure types of these structures as vertices of a simplex representing a space for economic policies and institutions. Each of these polar cases is characterized in the figure by both a set of rules of the game (by which allocations are implemented) and a set of preferences and social norms (associated with how they contribute to overall societal governance). The coordinates of any point on the simplex sum to one and represent weights giving the relative importance of state, market, and civil society (for any particular point in the space, the largest weight is the importance of the closest vertex.)

Figure 1 The space for institutions and policies with ideal-type forms of societal governance at the vertices, their implementation mechanisms and behavioural characteristics

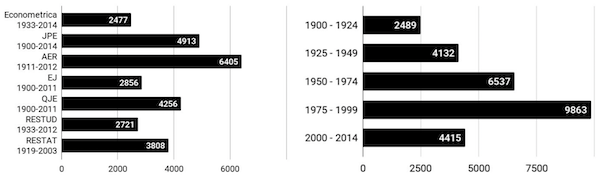

Here we document the emergence of civil society as an important set of themes in the corpus of papers published in the major economics journals in the UK and US between 1900 and 2014, a total of 27,436 articles (as shown in Figure 2). To represent this shift, we use topic modelling, a probabilistic machine learning technique that treats a corpus of observed data (the documents in Figure 2) as arising from a hidden data-generating process, the structure of which is to be estimated (Ambrosino et al. 2018, Ash et al. 2022, Blei 2012, Blei et al. 2003). The model provides an answer to the question: what thematic structure is most likely to have – hypothetically – generated the observed data (the distribution of words making up each document in the corpus)?

Figure 2 The corpus: Full text of 27,436 research articles by journal and year

Using variational Bayes methods, our topic modelling on the corpus in Figure 2 generated 100 topics (vectors of words whose weights measure the relative frequency of their usage) from the literature. The topics are generated by an unsupervised learning algorithm. We named them by hand based on their most heavily weighted terms. The technical details and rationale for the key assumptions of our topic modelling are in Bowles and Carlin (2020).

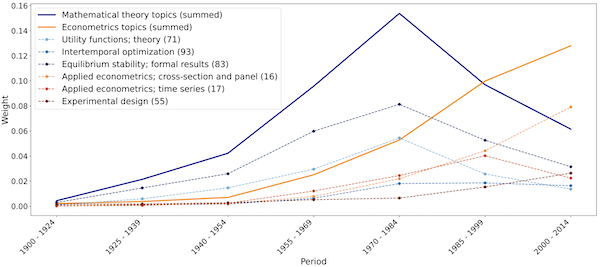

The lens provided by the topic model trained on this corpus records changes in the balance of attention given to themes relating to the state, the market, and civil society, grouping subsets of the 100 topics into one ‘metatopic’ at each of the vertices. Our procedure for assigning a topic to one of the three metatopics was to determine whether the words most heavily weighted in the topic are commonly associated with either the motivations or the mechanisms characteristic of the three vertices. Topics whose primary terms are unrelated to the three systems of societal governance (including those concerning mathematical or econometric methods shown in Figure 3) were not assigned to a vertex.

As would be expected, subtopics constituting a metatopic are clustered in the data. Across the documents in our corpus, if subtopics i, j, and h are respectively two subtopics of the same metatopic (i and j) and a subtopic not in the same metatopic (h), then the weights on i and j are positively correlated across documents while the weights in i and j correlate negatively (weakly) with the weights in h (Appendix 2). Illustrating our results, Figure 3 confirms the growth and decline of mathematical topics and the well-established increased focus after mid-century on empirical methods (Angrist et al. 2017).

Figure 3 Mathematical theory and econometrics topics since 1900

Notes: The weights shown are the relative frequency with which works in the corpus of each period drew upon the indicated topics. Weights in the earliest period reflect the infancy of mathematical and econometric methods at the time. The topic numbers shown in parentheses are arbitrary.

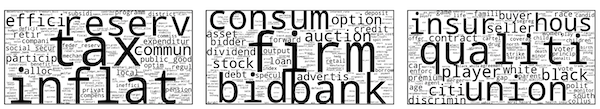

Word clouds showing the frequency of words in the 100 topics and the 10 papers drawing most on the terms heavily weighted in each of the three metatopics are presented online in Appendix 3. Figure 4, showing word clouds from these metatopics, gives an idea of their content. For example, important market actors – firms, banks, consumers – are prominent in the market metatopic.

Figure 4 Word clouds showing the most frequently used terms in the three metatopics respectively from left to right: State, market, civil society

To illustrate, examples of papers drawing heavily on the topics making up the three metatopics are: for market, Bain (1970) “Changes in Concentration in Manufacturing Industries in the United States, 1954–1966”, and Klemperer (1992) “Equilibrium product lines”; for civil society, Fudenberg and Tirole (1990) “Moral Hazard and Renegotiation in Agency Contracts”, and Fehr et al. (2007) “Fairness and contract design”; and for state, Saez (2001) “Using elasticities to derive optimal income tax rates”, and Feldstein (1978) “The welfare cost of capital income taxation”.

The Turn Towards Civil Society

Our topic model allows us to locate any particular text in the state space of Figure 1, including the entire corpus under study for various periods, shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5 Research in economics: The turn towards civil society themes from the 1970s

We see a significant movement in economic research between 1900 and 1970 away from state-related topics towards market topics, even as the economic importance of the state was growing. This shift was slowed, but not reversed, by the war economy of the early 1940s. The period after 1970 witnessed an equally large and uninterrupted shift towards civil society topics, primarily at the expense of market topics.

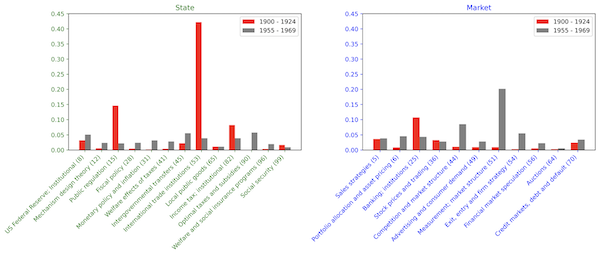

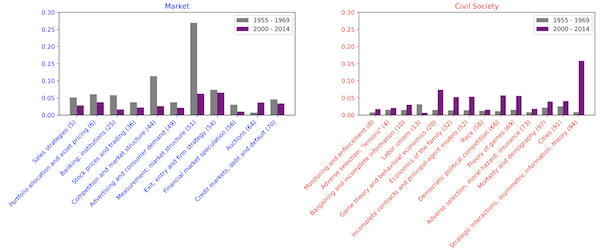

Figure 6 (upper panel) shows that the shift from the neighbourhood of the state vertex towards the market vertex prior to 1970 was due to dramatic declines in the weight of the topics that we named ‘public regulation’ and ‘international trade institutions’ along with a substantial increase in the weights of two topics concerning market structure. Figure 6 (lower panel) shows that the shift towards civil society over the last half century was due primarily to a reversal in the earlier increase in the weights of these two market structure topics and an increase in topics concerning asymmetric information, strategic interaction, and the behavioural foundations of economics.

Figure 6 The shift from research on state to market topics prior to 1970 (top panel) and the components of the turn toward civil society topics after 1969 (bottom panel)

Discussion

The evidence in Figure 3 suggests that the shift from state to market was associated with the increased use of mathematics, especially constrained optimization by (for the most part) non-strategic actors. This constituted a change in method – roughly the mathematical formalization of Alfred Marshall – rather than any novelty in the kinds of economic behaviour under study.

Changes in method – including models of limited information and strategic interaction – along with advances in quantitative methods were also a hallmark of the subsequent shift in research towards civil society themes. But unlike the earlier methodological shift, research after 1970 was characterized also by an enlarged conception of the economic behaviour under study.

Since the late 1960s, this occurred by the application of conventional economic tools to an expanded set of topics – as in the work of Gary Becker (1974, 1968) on the family and crime – and also through the application of novel insights from other disciplines to the conventional subject matter of economics, as in the work of George Akerlof (1982) and coauthors (1982) on gift exchange and cognitive dissonance, and of Oliver Hart (1989, 1995) on authority in the firm and the exercise of power by owners and managers.

What is civil society?

Google:

Civil society is a term that describes the range of non-governmental organizations and institutions that represent the interests of citizens, and promote a vision for society or politics. Civil society organizations are independent of the state, and can include:

Churches and other faith-based organizations

Online groups and social media communities

Nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and other nonprofits

Unions and other collective-bargaining groups

Innovators, entrepreneurs, and activists

Cooperatives and collectives

Civil society allows for the expression of individual ideas and development, and acts as a space for different interests to compete, compromise, and find solutions. In liberal democracies, civil society is generally more independent and has a broader space than in states that restrict individual freedoms.

“The turn towards civil society in economics that we document … is consistent with two propositions. The first is that much of what we think of as the economy consists of non-market interactions and exchanges… Second, in these and in other settings, ethical and other-regarding preferences have an important place…”

The essay is interesting, but after a thorough reading I do not know what the writers wish me to make of this turn in economics to civil society analysis. Why am I missing a central focus?

It seems they are making an observation and leaving its interpretation up to us. My interpretation is that economists, thinking they had the basics down, were branching out in an effort to subsume more and more into their market paradigm. Some were actually trying to do the opposite but by using only the acceptable tools they failed.

“My interpretation is that economists, thinking they had the basics down, were branching out in an effort to subsume more and more into their market paradigm…”

An important interpretation, which answers the question of why many economists have a disdain for the entire field of sociology. Brad DeLong of Berkeley has several times expressed this disdain directly to Berkeley sociologists; making a point of dismissing sociological analysis. I disagree with the DeLong criticism entirely.

Paul Krugman shows me a lack of necessary sociological understanding of institutions that seriously limits otherwise incisive economic analysis.

The lack of understanding and dismissal of sociology is for me the reason why Western economists so often appear incapable of understanding how China has been developing. DeLong will claim to be unable to understand Chinese development, but confidently predict an unraveling of the Chinese economy for years. Showing no inclination to question the self-claimed lack of understanding:

http://www.bradford-delong.com/2016/04/must-read-i-do-not-understand-china-but-it-now-looks-more-likely-than-not-to-me-that-xi-jinpings-rule-will-lose-china.html

April 5, 2016

I do not understand China. But it now looks more likely than not to me that Xi Jinping’s rule will lose China a decade, if not half a century… *

* http://www.economist.com/news/china/21695923-his-exercise-power-home-xi-jinping-often-ruthless-there-are-limits-his

— Brad DeLong